Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPLEASURE PRINCIPLE

Who should buy Renoir's perfect idyll of gai Paris, Au Moulin de la Galette? And why?

MARK STEVENS

Art

This month Sotheby's will sell one of the very few expressions of perfect happiness in modem art—Renoir's Au Moulin de la Galette. Owned for six decades by the John Hay Whitney family, this painting of a dance hall in Montmartre has an estimate of $40 to $50 million, which means it could set another record. The picture is the smaller (but not lesser) of two versions, the other being in the Musee d'Orsay. It is one of the greatest evocations of la douceur de la vie—of that side of paradise we locate in Paris.

You have doubtless noticed that paradise does not interest many modem artists. The brutishness of life is a much more congenial subject, more in keeping with the modem experience, and the sublimely "good" has always been harder to portray than the fascinatingly ' 'evil. ' ' So it is never less than astonishing when a modem artist succeeds in catching a genuine glimpse of paradise. Matisse may be the master here, especially in his pictures of the dance, but this dancing Renoir has the same miraculous spirit.

What amazes me is that I love Au Moulin de la Galette while disliking most of Renoir's art. The painter arouses such divided feelings because he portrays the best things in life—love, flowers, children, the innocent delights of light and color—in a way that can make one yearn for crabbed old men. So many sticky kiddies. So many girlie cream puffs. (And I enjoy the women in Rubens.) Renoir became the dessert chef of Impressionism, and his confections are maddening precisely because he was an artist of taste and intelligence.

He was at his best when keeping his eye firmly on the actual world beyond his fantasies. He once told Matisse, "When I have arranged a bouquet in order to paint it, I go round to the side I have not looked at." In the 1870s, having become interested in compositions that included more than one figure, Renoir spent several months observing the scene at Le Moulin de la Galette, an outdoor dance hall where Parisians liked to go on Sunday afternoons to dance, flirt, gossip, and sip wine.

He painted on the spot, a difficult undertaking, according to his biographer Georges Riviere: ' 'The wind blew and the big canvas threatened to fly away like a kite. . ." The picture that resulted is a kind of urban idyll. Even though the setting is not pastoral and there are no shepherds and piping flutes, the pleasures, like those of an idyll, have a radiant simplicity that makes all the complications of sophisticated urban life seem a terrible mistake. There is music in a garden, and young love is in full frolic.

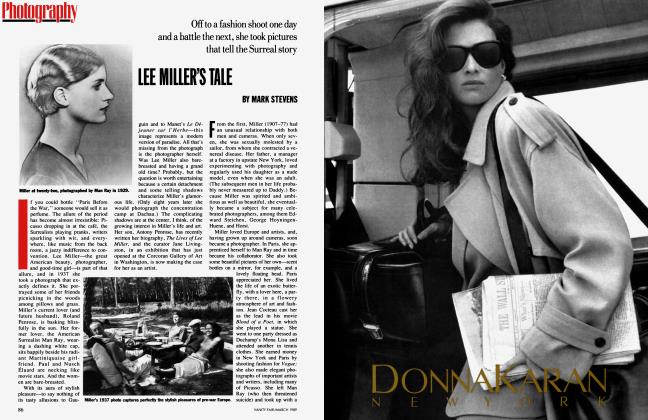

The pleasures of this picture contrast markedly with those in Manet's famous version of an idyll, Le Dejeuner sur I'Herbe, in which a naked woman is shown picnicking with some dressed men. The Manet is about sophistication, not joy; it invokes the idyll as a foil for a deliciously cool modem eye and takes pleasure in shocking the shockable. Like Manet, modem artists have often felt obliged to resist the blandishments of charm. In this respect, Renoir's picture seems truly innocent, conveying a sweetness more in keeping with Watteau.

The flirting of the girls in the foreground of Au Moulin is good-natured. No feeling of sexual threat intrudes on the easy afternoon, and like the idylls of the shepherds, the party is free of the burdens of snobbery and class: the stylishness seems artless. A generous dappling of light unifies the scene, helping convey the feeling of a thousand small things happening at once. The composition is calculated, yet not imprisoning; the child in the lower left half slips out of the frame, which is what children do. The artist has not interrupted time, catching everyone either off-balance or striking a pose, but has stolen into a moment as softly as one might wish so that the seamlessness of time can prevail. If the Impressionists understood that the modem must be momentary, Renoir also knew that a moment could provide all that's necessary.

The world of Au Moulin, like any paradise, seems complete in itself. Perhaps that is another reason the painting, despite its modem means, seems so different from most modem art. Not many artists, when they become playful or idyllic in feeling, would dare make something that is so much a "world" without the usual modem subtractions. There is no feeling here of edginess, absence, or alienation, none of the concern about masks and artifice that you find in other portrayals of dance halls, such as Toulouse-Lautrec's; the bohemian spirit of the painting seems free of any costs. In his greatest paintings, Matisse removed paradise to a realm of pure imagination and form. In Au Moulin, Renoir could still locate a joy that was of this world. He made the "Paris of dreams" palpably real.

This is the Paris to which Americans have always seemed so susceptible. It was probably the frosty Puritan background, the heavy-handed respect given to money and duty, that led so many wealthy Americans of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to fall in love with the light brush of Impressionism. Henry James once said that "summer afternoon" were the two most beautiful words in the English language, and in his novels

Paris often plays the part of a stylish temptress. Americans went to Paris for gaiety, idealizing the artful perfection of the senses that they missed at home.

John Hay Whitney bought the painting in 1929, when only twenty-five years old. (He died in 1982.) He came from a patrician family and led a distinguished, responsible life, founding a venture-capital firm, forming a great art collection, and becoming the American ambassador to the Court of St. James's. What fascinates me is that this Renoir was among the first paintings he bought. He paid $165,000, a princely sum in 1929. How remarkably bold. What a good eye. Whitney must have recognized the charm that Paris still held for young moneyed Americans in the 1920s, many of whom hoped to find paradise in a party. Many other people would now like a piece of this party, of course, but the truth is, any desire to own the picture seems misguided. Big money should not barge into this easygoing place. No one should try to possess a moment that is so free. Not the Whitneys, not a museum, not the Japanese, not a corporation. I like thinking of the picture being painted on the spot, in danger of being blown away like a kite.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now