Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowL.A. CONFIDENTIAL

Media

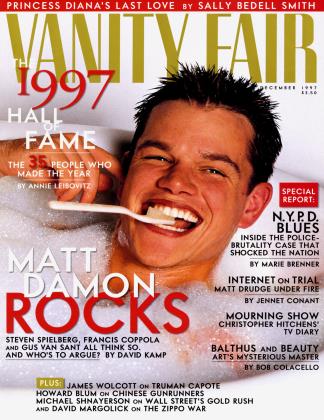

What happens when a computer wonk gets a cult following among the media and Washington elite? For Matt Drudge of the Drudge Report, fame and trouble. A White House aide is suing the "Walter Winchell of the Web" in a libel case that could change the future of on-line journalism

JENNET CONANT

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

It's hard to say exactly when Matt Drudge arrived at the dangerously combustible center of the media universe. How he got there, however, is no mystery.

There was the day Drudge surprised New York Times reporter Todd Purdum by casually greeting him on Wilshire Boulevard just weeks after Purdum had moved west to become the Times's Los Angeles bureau chief. "So," Drudge said, "how do you like being in town? Found a house yet?" "I thought he was the C.I.A.," says Purdum, who says he is rarely recognized on the street.

There was the day Times columnist Maureen Dowd was trying to keep a low profile at an ABC press briefing, when Drudge materialized out of nowhere and began quizzing her about what she was up to. Not only did he recognize the writer, he told her that he and his friend Anita Hill-bashing writer David Brock had once paid a surprise visit to her Washington town house, hoping to catch her frying an omelette. But she wasn't home. "You know where I live?" Dowd reportedly asked in horror.

Then, last April, there was Drudge at the White House Correspondents' Association Dinner, where he nearly eclipsed the newly uncloseted Ellen DeGeneres and Anne Heche. "People thought it was pretty cool," says James P. Pinkerton, a Newsday columnist who took Drudge to the event. "He's very nice and fun and full of gossip."

CONTINUED ON PAGE 165

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 160

By late June, Drudge was the guest of honor at a party thrown by Brock and Laura Ingraham, the Jenny McCarthy of conservative television punditry. A large, bipartisan crowd welcomed him at Brock's N Street town house—everyone from Michael Huffington to Mandy Grunwald. Newsweek's Howard Fineman told Drudge he was "the biggest thing to come along in journalism since Hunter S. Thompson." (Drudge had never heard of Thompson.)

Drudge, a self-invented gossip who idolizes Walter Winchell and Louella Parsons and bills himself as an "oldfashioned troublemaker," had become the Internet's newest celebrity—all because of the Drudge Report, his quirky, starstruck on-line gossip column about the media. Unlike anyone before him, Drudge covers the subcelebrity world of news, journalism, and politics with the sort of breathless enthusiasm usually reserved for movie stars and models.

Any day of the week, at any hour—he has no editor and no deadlines— Drudge E-mails new material to those on his mailing list, which he says has swelled from nothing in 1995 to an estimated 85,000 today. The material is also posted at his Web site, which America Online made readily available to its eight million subscribers last June—and that doesn't include the countless others who copy his "CodeRed Bulletins" and send them to friends. Along with his timely dispatches, Drudge provides a handy compendium of newspapers, wire services, and syndicated columns.

iscovering an easy point-and-click route to their favorite papers, and delighting in an opportunity to dish their peers ("confidentiality assured"), reporters began making Drudge a daily habit—even more so after he ferreted out Whitewater gossip, such as when independent counsel Kenneth Starr decided against leaving his post to accept two deanships at Pepperdine University. Journalists and politicians were drawn to Drudge because of their shared vanity: here was someone who was paying attention, and who even considered them glamorous.

That Drudge was a rank amateur with bad grammar and no institutional backing didn't seem to bother anyone. The prevailing attitude toward Drudge was that he was an outsider unburdened by the rules of mainstream journalism. Drudge, who has no formal training, puts a small disclaimer at the bottom of some reports: FOR RECREATIONAL USE ONLY.

"If Sidney wants to track down people who are smearing him," says Mary Matalin, "he'd better get another job."

"No one ever made a bet, based on anything they read in Drudge, that Bill Clinton has an American eagle tattooed on his you-know-what," James Pinkerton says of one of Drudge's more improbable items. (Actually, Drudge had reported it was on the president's leg.)

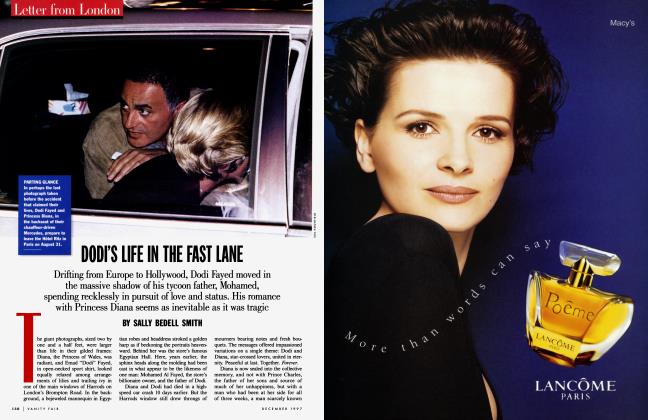

While Drudge kept churning out his so-called "gotcha" stories, he was too inexperienced to realize he was playing with fire. He learned his lesson on Sunday, August 10, when he posted the headline CHARGE: NEW WHITE HOUSE RECRUIT SIDNEY BLUMENTHAL HAS SPOUSAL ABUSE PAST. The next morning, Drudge's subscribers received this item by E-mail: "The DRUDGE REPORT has learned that top GOP operatives who feel there is a double-standard of only reporting republican shame believe they are holding an ace card: New White House recruit Sidney Blumenthal has a spousal abuse past that has been effectively covered up. The accusations are explosive."

The story had a typical Drudge media angle, comparing the "cover-up" with the case of Republican political consultant Don Sipple, who had been the subject of wife-beating allegations in Mother Jones, a liberal magazine. (Sipple denies the charges.) In his column, Drudge quoted "one influential republican" as saying that "there are court records of Blumenthal's violence against his wife"—Jacqueline Jordan Blumenthal, who runs the White House Fellowships Commission. Drudge also quoted a White House source who dismissed the charge as pure fiction that "has been in circulation for years."

Blumenthal had seen the headline when he read the Drudge Report on Sunday evening. The timing was exquisite. Monday was to be his first official day in his new White House job as an assistant to the president. When Jacqueline Jordan Blumenthal arrived at her office at 7:30 Monday morning, she found the story on her fax machine. It had been sent by Nicholas Thimmesch II, a former press secretary for Oklahoma representative Steve Largent, a Republican. Thimmesch claims he faxed the Blumenthals "for my own purposes."

Within 24 hours, Drudge had received a strongly worded letter from Blumenthal's lawyer, William McDaniel. Drudge promptly posted an on-line retraction and apologized.

Hut the Blumenthals, who have been married for 21 years and have two children, were not satisfied. Drudge had failed to comply with the terms of their letter, which concluded: "Before proceeding against you, Mr. and Mrs. Blumenthal want to give you an opportunity to disclose to them the following: the names of the 'top GOP operatives who feel there is a double-standard' and who believe 'they are holding an ace card'; the name of the 'influential republican' who demanded anonymity; the court records you claim document Mr. Blumenthal's acts of domestic violence; and the name of the 'White House source' whom you purported to quote." The letter also said that if the information was not provided by five P.M. the next day, the Blumenthals would take action.

Drudge did not reveal his sources, and the Blumenthals filed a $30 million defamation suit against him and America Online. "If Drudge had done anything at all to verify the story, he would have discovered it was false," McDaniel said in a press release he circulated with the 137-page complaint. Just as significant, Blumenthal had the backing of the two most powerful men in the country. "The president and the vice president separately expressed support for me— personally," says Blumenthal. "They did it in terms of defending my family and their shared disgust that people can be smeared like this."

Later, he adds,"Though the charge might sound absurd—it's like a very old joke: 'So have you stopped beating your wife?'—it's astonishing how insidious it is. Your life can be cast under a shadow instantly and many people put you under suspicion, even people who have known you for years."

"It's a fairy tale gone nightmare, the media ricochet," says Drudge, who reluctantly agreed to be interviewed by Vanity Fair. We met at the Ivy, the bustling Los Angeles restaurant. When I arrived, he was hovering nervously near the entrance. He is a slight 30-year-old with a receding hairline, and he was wearing khakis, a button-down shirt, old-fashioned brown wing tips, and an air of stylized eccentricity reminiscent of a young Woody Allen.

Drudge won't talk directly about the case—or his reporting of the Blumenthal story—but concedes that fighting a lawsuit sanctioned by the president is "scary." As for his colleagues in the media, he adds, "They are already writing about me in the past tense."

It has become a favorite Washington parlor game to guess who Drudge's sources were and what their motives may have been. Blumenthal's complaint contributes to the game by speculating that the sources wanted to see him lose his job. McDaniel told The Washington Post that Drudge's story was "a despicable and cowardly attempt at political assassination."

As much as anything, it seems, Blumenthal wants to unmask Drudge's sources. "They have committed defamation, too, and we will sue them just as soon as we find out who they are," says McDaniel. But he insists the case should not be viewed in political terms, and says he is not being paid by the White House or any liberal defense fund. "I'm not a politician—I'm a lawyer," he continues. "If it were a liberal saying this about a Republican, it would be just as bad. And I think a lot of Republicans think so."

"It's a fairy tale gone nightmare," Drudge says. "They are already writing about me in the past tense."

While agreeing that it was a terrible thing to print about anyone, some Republicans feel Drudge may have been used by far more cynical minds. As Drudge acknowledged in The Washington Post shortly after he had retracted the story, "Someone was trying to get me to go after [the story] and I probably fell for it a little too hard. I can't prove it. This is a case of using me to broadcast dirty laundry. I think I've been had." Drudge has claimed that he tried to reach Blumenthal before he went with the story; Blumenthal says there is no record of any message. Drudge also says his reputation depends on the accuracy of his report, adding, "I put my name on it."

"It's pretty unfortunate," says David Brock, who blames Drudge's error on the immediacy of the Internet. "He could literally have been on the phone and writing it down." Brock has heard the rumors that he is one of Drudge's sources and denies it, saying, "Hell, no." But he has an idea who some of Drudge's sources are, and he is not impressed. "He took stuff from the far-right-wing fringe," says Brock. "He wrote a lot about Hillary, relying on the tomorrow-indictmentsare-coming-down crowd," a reference to a previous Drudge item: a report last year that Hillary Clinton would be indicted.

"The [Blumenthal] rumor had been going around for 10 years— not just in right-wing circles," says Andrew Ferguson, a senior editor at the conservative Weekly Standard. "People always claimed someone had seen the copy of divorce papers saying he beat his wife." Ferguson has met Drudge and thinks of him as the kid who sits by the Xerox machine all day and repeats everything he hears. "It's precisely the kind of thing, in his naivete and credulity, he would buy. You get the feeling he hasn't been around long enough to know what he should go with."

In right-wing circles, the Blumenthal I story is stale gossip that has been peddled for years by, among others, The Wall Street Journal's controversial editorial-page writer, John Fund, who is known for using his column to bludgeon his political enemies. Two conservative reporters vividly recall being present at a party with Fund in 1994 at which he told guests that he had "seen the police reports" indicating that Blumenthal was "a wife beater." A third conservative says he heard it from Fund. After the item about Blumenthal ran, David Brock, in an effort to track down the story, called friends around town and says he soon learned that "Fund had been telling people at parties in Washington this summer that he had seen the police blotters."

This does not mean that Fund was Drudge's direct source—just that he has apparently circulated the story. Fund acknowledges that he subscribes to Drudge's service, but says he has never "spoken with, E-mailed, or had any contact with Matt Drudge." But he acknowledges having heard the Blumenthal story. "The rumor was in circulation around town and a lot of people repeated it and commented on it. When four or five people have a conversation, there's lots of cross talk. I cannot remember ever having referred to 'police blotters' in any shape or form." He adds, "I think that party conversation in Washington, as a result of all this, will be much more constrained—that's apparently what some people want."

Clearly, conservatives had found a useful weapon in Drudge. "The right, in general, have always been much more Internet-sawy, and most likely realized the value of Drudge from the beginning," says syndicated columnist Jim Glassman, a former colleague of Blumenthal's at The New Republic.

Here's the main reason that BlumenH thal has been a favorite target: at The New Republic and later, as a political writer for The New Yorker, he was widely regarded—and derided—as the Clintons' chief journalistic advocate. He routinely jumped to their defense and often feuded with journalists who criticized his close personal friends the president and the First Lady. He has long clashed with much of the Washington press corps, which dismissed his writings as obnoxious, unprofessional toadyism. Many felt he crossed the line during the 1996 Republican National Convention, when he was overheard saying, "Maybe Bob Dole will drop dead."

Last June, when it was announced that Blumenthal would finally be joining the White House payroll, even The New Republic suggested that he be given back pay. And Washington Post media columnist Howard Kurtz wrote that Blumenthal had "been branded as the capital's chief suck-up." Blumenthal believed that his loudest critics in the media are anti-Clinton crusaders who are out to get him. "They play by different rules," says Democratic media consultant Mandy Grunwald. "They just make shit up."

'This is a case of trying to use me to broadcast dirty laundry/' Drudge says. "I think I've been had."

Meantime, conservatives are attacking BlumenthaFs motives. "Sidney's going after the sources because he thinks one of the sources is attached to big money," says Mary Matalin, President Bush's former deputy campaign manager. She has used her daily radio show to champion Drudge as a victim of the "Clinton attack machine." "Sidney isn't a wuss. He knows what politics is. It's not jacks. There is a lot of hypocrisy going on here. Sidney Blumenthal is not exactly known for his meticulous reporting. If he wants to spend his time in politics trying to track down the people who are smearing him, he'd better get another job."

Even some of Blumenthal's liberal colleagues think he may have filed the suit to please his boss. "My impression of the Clintons is that you can't beat up on the press too much for their taste," says Eric Alterman, a liberal journalist who teaches media studies at Hofstra University. "And they form Sidney Blumenthal's core constituency."

Alterman thinks lawsuits of this kind set a dangerous precedent, and he should know. After Alterman wrote a scathing article in The Nation critiquing The New Republic under then editor Michael Kelly, Kelly called Alterman a "pathological liar" in George magazine. Alterman reportedly told a colleague that Blumenthal, through a mutual friend, had urged Alterman to sue Kelly for damaging his reputation. (Alterman declined to comment on a private conversation and Blumenthal denies it.)

li y his own admission, Drudge is "not K that ambitious." His dream is to one m3 day work for Daily Variety. As a kid, he delivered The Washington Star and preferred reading Mary McGrory's columns to doing homework. He graduated 325th out of 350 in his class at Maryland's Northwood High School and never attended college. He then spent several aimless years in New York before heading to Los Angeles in the mid-80s, when he landed a job in the gift shop at CBS Studio Center. In January 1996, at age 28, Drudge quit his $30,000a-year store manager's job to devote himself to his Internet column.

Working in a cramped $600-a-month Hollywood apartment—a friend calls it "Geek Central"—and using an old Packard Bell computer that his father had given him, Drudge began E-mailing his dispatches to various news groups, such as alt.politics and alt.showbiz.gossip. He dug through the CBS trash bins for ratings and other scraps of network news. His first big scoop came when he obtained a memo reporting that Jerry Seinfeld was demanding $1 million an episode.

Aided by a network of anonymous E-mail and chat-room sources—including what he claims are a number of White House staffers—Drudge began landing bigger scoops: CBS fires Connie Chung, Bob Dole picks Jack Kemp as his running mate. "I am a menace," Drudge says. "What I do is new and it's changing news cycles." He adds, "I ask questions—that is my right as a citizen."

A news junkie, Drudge rises at nine and immediately scans the wire services, then spends the rest of the day talking to his sources. (He has a side interest in weather and regularly reports on unusual climatic phenomena.) Drudge reads 30 on-line papers a day, watches three television sets (C-SPAN is a favorite), listens to talk radio, and monitors a police scanner. "You live with it," he says of the constant stream of information. In the late afternoon, he reads the next day's London Times and The Daily Telegraph to get a jump on the American press.

"What I love about him is that he is weirdly innocent," says Michael Kinsley. Kinsley was so impressed with Drudge that he tried to hire him last spring. "He's using the Web in a very effective way. And he's a nut, and I like nuts."

"What I do is only outrageous because of the period we're in," says Drudge, who perhaps fails to appreciate the human toll his reporting can take. "If you compare it to what was written in columns in generations past, it's tame now. Back then, there was real intensity—'So-and-so is a Communist.' What I do is nothing like what Winchell did. It's just echoing in a really cavernous media world where there is nothing to buffer provocative writing."

n July 3, Drudge began his transformation from office gossip to national newsmaker when he reported that Newsweek Washington correspondent Michael Isikoff was working on a damning story about Kathleen Willey, a former White House employee subpoenaed by Paula Jones's lawyers because she could allegedly testify that Clinton had "sexually propositioned" her on federal property. The item enraged the Establishment press, but Drudge became the toast of talk radio. Isikoff called him "a menace to honest journalism" and ultimately published an article that simply reported both sides of the story.

But according to Newsweek's Howard Fineman, Drudge merely used oldfashioned reporting techniques to get the Willey story. "He waltzed into the bureau and started nosing around," Fineman says. "Drudge approached us the way we once approached political institutions. This little mouse of a guy has everyone up on their chairs."

Drudge boasted that White House staffers visited his Web site 2,600 times in the days after his Isikoff report. Because of his scoops, there was concern that he might somehow be hacking into office computer systems and reading files. "I have Windows 95—it's plug-andplay," says Drudge, whose computer skills are self-taught. "How did Woodward get Deep Throat? That's the same way I get sources. People come forward."

I ow Blumenthal wants Drudge to pay— Nand he has the legal and financial IV means to see that he does. Drudge is not so fortunate: he supplies his on-line report for free and lives off his modest, four-figure monthly royalty from America Online. "It's just me and my two cats," he says. "I clip coupons." As we leave the restaurant, I can't help noticing that he bypassed the valet parking and wedged his red Geo into a metered spot a short walk away.

"I am a menace," Drndge says. "I ask questions-that is my right as a citizen."

As soon as news of the litigation spread, Blumenthal's enemies came out of the woodwork to embrace Drudge. The first was David Horowitz, the bestselling political biographer (with Peter Collier) and a former leader of the New Left who underwent a conservative political conversion late in life. "He offered to set up my legal-defense fund," says Drudge, sounding cheered at the prospect. "He's the trustee." Horowitz has seen to it that Drudge has expert pro bono legal counsel in Manuel Klausner, who is on the board of the Reason Foundation, a libertarian think tank.

Drudge is a registered Republican, but when I ask him about his politics, he seems fairly unformed. "I am anti-big-government," he says mildly. Drudge insists that his reporting is nonpartisan. "It's just about going out there and checking what's going on in the offices in Washington. Whoever's in the White House next will get my undivided attention."

"He is a new-paradigm populist," says Mary Matalin. "He is an entrepreneur. He has joie de vivre and the people like him." It just so happens that most of those who do are conservative. In 1995 Drudge won the endorsement of Rush Limbaugh, who called him "the Rush Limbaugh of the Internet." (Drudge countered by calling Limbaugh "the Drudge of radio.")

I f Drudge was only opportunistically I conservative in the past—simply takI ing dirt from the best shovelers—the Blumenthal suit has put him solidly in the conservative camp. "If somebody cast an unjust aspersion on Blumenthal," says David Horowitz, "it couldn't have happened to a more deserving guy. He made his reputation throwing sleaze at people."

The feud between Horowitz and Blumenthal dates back to the 1987 Second Thoughts Conference, which Horowitz helped organize. Blumenthal apparently did not approve of the conference, which called for the rejection of certain 60s ideals, and wrote a savage article for The Washington Post about the founders of the New Right. Horowitz, he wrote, "left his wife and three children" after abandoning radicalism.

"He portrayed me in a defamatory fashion," says Horowitz, who claims the story was filled with errors. "I have four children, by the way. I never abandoned them. And it took seven or eight years for my politics to change." Horowitz says he considered suing, but instead complained to the Post's ombudsman. "Who hasn't made a mistake, particularly when politics is involved? . . . There isn't anyone in this game who hasn't circulated something they shouldn't have. . . . But to try and bring down a writer—and for the White House to be behind it!"

"Everything I've seen shows me this is a compelling case for Matt Drudge, and shows this case should never have been filed," says his lawyer, Manuel Klausner. "Leaving aside the issue of whether or not the statement was false, Matt provided an immediate retraction and apology. And at the time he printed it, he believed the information to be accurate, which is very significant from a legal standpoint." If Blumenthal is considered a public figure, he must prove that Drudge acted with actual malice or reckless disregard of the truth, and that he published information that he knew was not true or had serious doubts about.

Klausner says that Blumenthal is bent on destroying Drudge. "The problem for the White House is not that Drudge is inaccurate," he says. "The problem is that Drudge is too accurate."

"The problem for the White House is not that Drudge is inaccurate," says Manuel Klausner. "The problem is that Drudge has been too accurate."

With so much legal machinery set in motion, the Blumenthal suit could break new ground in the relatively new field of Internet case law. Blumenthal and his lawyer believe the lawsuit is a healthy development, but others aren't so sure. "The good news about the Web is there are no barriers to entry and you do not have to pay for a printing press," says Steven Brill, the publisher and editor of a new magazine, Brill's Content, which will cover media issues. "The bad news about the Web is that there are no barriers to entry and you do not have to pay for a printing press. Because this was America Online, he took on an importance and patina of credibility."

The suit raises the question of whether cyberspace should be governed by the same rules that apply to the general media. Is AOL just another communications carrier, like the phone company—one that isn't responsible for anything it broadcasts? Or is it like a network that's legally required to exercise editorial control? The answer is unclear, and Internet providers are paying close attention. "There is a false notion, which has great currency in cyberspace, that they live in a law-free zone," says First Amendment expert Floyd Abrams. "But as regards Drudge, he's subject to the same libel laws as everyone else, and should be."

America Online believes it is covered by Section 230 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which states: "No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider." AOL spokeswoman Wendy Goldberg says, "We have seen the complaint and believe it has no merit."

But Blumenthal's complaint alleges that America Online knew exactly what it was getting into when it hired Drudge. The company even trumpeted the arrangement in a press release, which read: "Giving the Drudge Report a home on America Online (Keyword: Drudge) opens up the floodgates to an audience ripe for Drudge's aggressive brand of reporting."

"The lawsuit might be healthy, as much as I hate to say it," concludes Brill. "It could be the best thing that ever happened to the Web. It could be a wakeup call. Did anybody ever say, Wait a minute? What was AOL thinking when they signed him up?"

et while most journalists and editors agree that Drudge made an appalling error, they don't think Blumenthal should make a federal case out of it. "If it's a flat-out lie," Jim Glassman says, "I don't mind if Sidney sues as an individual. But I don't think that the White House should stand for this as a matter of policy. It could have a real chilling effect."

The first signs are already evident. Michael Kinsley had been planning a regular feature for Slate tracking the tabloids, until the Blumenthal suit came along. "We had to put it on ice because of the increased concern over lawsuits," Kinsley says. "The whole Drudge business—and suing America Online—has raised the ante on this sort of thing."

Kinsley falls back on the adage that every dog gets one bite. "Drudge went too far and he should be taken out and spanked," he says. "I can't defend what he is doing, but I think it would be very sad if he had some sort of scarlet L stamped on his chest because of this. When you think of the nefarious scumbags—the Oliver Norths, the Dick Morrises, the list goes on and on—who go on to have big careers, certainly it would be ridiculous if Matt Drudge was effectively silenced."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now