Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

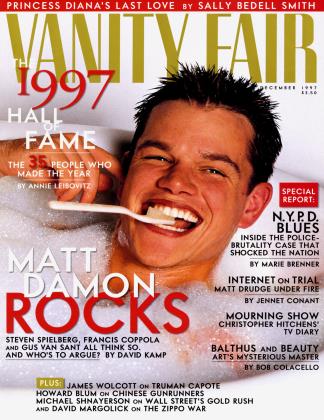

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE TRUMAN SHOW

George Plimpton's new oral biography of Truman Capote provides a sound-bite seance for a life in three acts: the Breakfast at Tiffany's beginnings, the In Cold Blood crescendo of acclaim, and the bitter finale of Answered Prayers

James Wolcott

Truman Capote was the most extraordinary literary exhibit of the talk-show era. Bizarre as he looked and sounded (his highpitched voice could scrape paint), he was perfect for TV. In a medium which prizes closeups, Capote was all head, and what a head, a magic lantern lit with mischief. Its bulging size and lolling movement, offset by his baby-blond hair and the lizard flick of his tongue, fixated the camera and filled the screen. He was more than telegenic. A debauched angel with a bourbon drawl, the likes of which had seldom been spotted outside of Tennessee Williams's swamp mists, Capote had a knack for the swift kill of the sound bite. On David Susskind's Open End show, he dismissed Jack Kerouac*s work with the still-quoted remark "[It] isn't writing at all—it's typing." Years later, he rollicked Johnny Carson's audience by claiming that the author of Valley of the Dolls, Jacqueline Susann (with whom he was feuding), resembled "a truckdriver in drag"—a wisecrack that sent Susann and her husband reeling to their lawyer, Louis Nizer. As Capote grew older, his mind aslosh with alcohol and drugs, he lost pinpoint control of his poison darts. In one of his late-70s TV appearances on New York's Stanley Siegel Show, he affected a fey Rip Torn persona ("I'll tell you something about fags, especially southern fags. We is mean. A southern fag is meaner than the meanest rattler you ever met ... ") and laced into his former friend Lee Radziwill, his face puffy, his diction gummy, his words seeming to wander off on their own. The TV screen, which had been his vanity mirror, turned into a CAT scan of a mind in public ruin.

6 Capote had a knack for the swift kill of the sound bite. 9

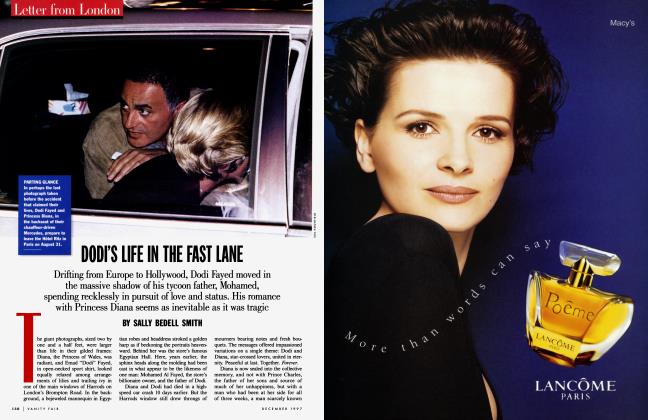

These three TV appearI ances correspond to the I three stages of Capote's career, as he himself conceived it. Act I was the golden-boy period of Other Voices, Other Rooms, published in 1948 (the year of such heavy clompers as Norman Mailer's The Naked and the Dead and Irwin Shaw's The Young Lions), culminating in the critical and popular success of Breakfast at Tiffany's a decade later; Act II was the arduous climb and excelsior cry of In Cold Blood, which brought him wealth, magnified fame, and critical acclaim; Act III, the mandarin phase, was pledged to Answered Prayers, his magnum opus about the emaciated courtesans of the ruling class that would be his Proustian feast for posterity. As his performance with Stanley Siegel suggests, Act III proved to be a bitter anticlimax; instead of a grand finale, the curtain came crashing down on Capote's head. Not only didn't he complete Answered Prayers (boogying the night away at Studio 54 may have unfastened the girdle of his Flaubertian resolve), but the parts that were published cost him the friendship of the Fine Bone Structure socialites Capote called his "swans"—most prominently, Nancy "Slim" Keith and Barbara "Babe" Paley. He was ostracized and traumatized. His last years were a sad muddle of blackouts and ambulance rides.

This doesn't dampen interest in Capote. If anything, the opposite. For many, the fizzle of Answered Prayers and his personal tailspin offer a spectacle more engrossing than the perfect arc of a distinguished life. A dignified exit may be desirable in principle, but if you can have your subject bumming around in his bathrobe in public, then you've got yourself a Cautionary Tale. There but for the grace of God and an empty liquor cabinet go I. Capote's star-crossed life, chronicled in a superb biography by Gerald Clarke published in 1988 (and currently being reissued by Ballantine), is being examined under the celebrity spotlight again this month in George Plimpton's Truman Capote (Nan A. Talese/Doubleday).

I know what is being said about me and you can take my side or theirs, that's your own business.

—The opening sentence of Capote's first published story, "My Side of the Matter," Story magazine, 1945.

Like Edie, the biography of Edie Sedgwick that Plimpton edited with Jean Stein, Truman Capote is an oral documentary which consists of quotes from interviews edited into snack-size sound bites: Memory McNuggets. What's eerie is how many of these remembrances issue from the ether. Diana Vreeland, Slim Keith, Leo Lerman, Herb Caen, Diana Trilling, Kathleen Tynan, Irving "Swifty" Lazar, the team of Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale—all have died since the interviews were conducted. With its ghostly chorus, the book is both a seance and a memorial service—a memorial service for Capote himself and a requiem for the prehippie postwar era, before hedonism hardened into decadence, when society still had a capital S but had begun to loosen its pearls and swing. Like Breakfast at Tiffany's Holly Golightly, Capote's most enduring creation, Capote was a starry-eyed opportunist, but unlike her he didn't drift up, down, and sideways like a stray boa feather. His social ascent, which carried him from the swimming holes of his native Alabama to luxury yachts anchored in the Mediterranean Sea, was one of the great solo guerrilla operations of the century.

ACT I

orn in 1924, Capote grew up in a small town in Alabama, next door to Harper Lee, who would later write To Kill a Mockingbird, basing one of its characters on him. Divided natures are nothing new to artists (who, more than most people, are both subject and object, civilian and spy), but Capote was figuratively and physically split in the middle. As the writer John Malcolm Brinnin recounts in Plimpton's book, hereafter known as T.C., "Willowy and delicate above the waist, he was, below, as strong and chunky as a Shetland pony." A centaur with a Napoleon complex, Capote combined the dreamy hypersensitivity of a poet with the push and stamina of a Balzacian upstart from the provinces. Forced to fend for himself after his mother, Nina, left him behind to glam it up in New York (his biological father wasn't really in the picture), Capote "never had a center in his life," according to one of his aunts, and the archivist Andreas Brown says that "Truman's whole life was haunted by abandonment." This sense of isolation made him adaptable, fanciful (he was always thinking up stories), and as acutely observant as only those who take nothing for granted can be, but it also robbed him of any inner anchor. He would complain later of lifelong "freefloating anxiety"—what Holly Golightly called "the mean reds."

Being the center of attention at least gave him a fixed position. When Capote was in the second grade, he learned that he would be leaving Alabama to live up North with his mother. "He said he wanted to throw a party so grand that everybody would remember him," Jennings Faulk Carter, a cousin, recalls. He decided to host a Halloween costume party, and created elaborate games for the other children to play. The party was nearly stampeded by a visit from the Ku Klux Klan, who had heard tell that there might be Negroes present and set upon one scared (white) boy dressed as a robot, whose cardboard legs prevented him from fleeing. After Harper Lee's father and other powerful townsfolk gave the sheeted rednecks the big stare, the Klansmen slunk off to their cars. With its giddy buildup and unexpected drama, this going-away party was the forerunner to the masked Black and White Ball Capote would host for Kay Graham in 1966, a night of operatic intrigue which was the Woodstock of the tuxedo brigade. (Don DeLillo devotes a chapter to its mythos in Underworld.)

'Capote claimed that everybody found him irresistible.'

While still in his teens, Capote was hired as a copyboy at The New Yorker. The editor, Harold Ross, looked askance at his flouncing down the corridors "like a little ballerina," in the words of one spectator. The cape Capote wore in the office also probably added an inch or two to Ross's porcupine hair. Copyboys and girls come and go at The New Yorker, they flicker like fireflies, so it was a shock to some of the old gray mares at the magazine when Capote's debut novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms, was published and they realized that this poppet had such confident prose in him. A precocious marvel when it appeared, Other Voices, Other Rooms has been severely marked down in recent decades (Cynthia Ozick took a mallet to the novel in her collection Art and Ardor, pounding it as paste jewelry), part of a general devaluation of the whole school of Southern Gothic, whose carnival-sideshow grotesqueries seem rather faded and clown-forlorn now. The stories in A Tree of Night (1949) and the novel The Grass Harp (1951) were likewise gaudy and impressionistic. If Capote had continued manufacturing pathos and plastic honeysuckle, he might have occupied the same small but durable niche today that Carson McCullers (The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter) does. His book of travel essays, Local Color (1950), an attempt to widen his compass, was a series of exquisite watercolors in prose—the descriptions so preciously sweet, he seemed to be writing with a peppermint stick.

Breakfast at Tiffany's was Capote's Houdini escape into open air. Originally set to be published in Harper's Bazaar until an officious dolt in the Hearst hierarchy interfered (it could be said of him what was said of the editor who rejected Poe's "The Raven": Congratulations; you goofed), the novella, although set in the 40s, conveys the champagne fizz and sparkle of fashion magazines in the 50s, the infusion of frisky new energy into old money. It's all surface, but the surface dances. A call girl and gold digger, Holly Golightly tears through the lives of those around her like a small duster, her flighty narcissism making her as hard to lasso as the most enigmatic European beauty emoting for eternity. Breakfast at Tiffany's captures that period in everyone's life in the city when new acquaintances offer fresh avenues to experience, and even bad experiences feel like initiation rites. Critics drew parallels between Holly Golightly and Christopher Isherwood's Sally Bowles, but the desperate yearning enveloped in Holly's wheedling charm expressed Capote's own desire to be admitted into the V.I.P. room. The writing is eager and limber, drained of southern (mil)dew, offering the prospect that Capote might become the petit maitre of cosmopolitan tales, a Maupassant of the cocktail hour. It was not to be. He had a masterpiece to hammer.

ACT II

On November 15, 1959, a couple of lowlifes named Dick Hickock and Perry Smith descended on the Kansas farmhouse of Herbert Clutter and his family. The two jailbirds had been tipped in prison that there was a large stash to be taken from the farm, but robbery turned out to be incidental. They slaughtered the Clutter family, leaving blood and hair on the walls, escaping with a measly 40 or 50 dollars. On assignment for The New Yorker, Capote went to Kansas to investigate the case (which at that point was still unsolved), accompanied by Harper Lee. In Cold Blood would take six years to research and write, its publication delayed not only by the reporting involved but by the need for dramatic resolution. Capote befriended Hickock and Smith (some say fell in homoerotic love with Smith), but friendship be damned— for the good of the book, for the sake of justice and symmetry, they'd have to die. The composer Ned Rorem recounts that in 1963 Capote confided that his book "can't be published until they're executed, so I can hardly wait." Two years later, he was still pacing. Kathleen Tynan, the wife and biographer of the critic Kenneth Tynan, says, "In the spring of '65 Ken met Truman, I think, at a Jean Stein party. The decision had just been made that the guys would be hanged and Truman, according to Ken, hopped up and down with glee, clapping his hands, saying, 'I'm beside myself! Beside myself! Beside myself with joy!"' When he witnessed the actual executions, Capote went wobbly and wept, and his description of the executions in the book has a penitential dolor. But his original jig can't be ignored. Critics and pundits interpreted the book, and the movie made from it by Richard Brooks, as a statement against capital punishment-sheer piety.

'Capote put his faith in the fools gold of gossip.'

In Cold Blood is self-consciously classical in its structure and presentation. It has a churchly sense of its own high aspirations. Capote wanted to prove that he could be the interpreter of the invisible eye of God, that he could divest himself of literary plumage and delve into evil and death. The Clutters—mom, pop, son, daughter—are ready-made symbols: the model American family, America in microcosm, their murders a blow to the heartland and a desecration of the American Dream. Such elaborate foreplay went into the promotion of In Cold Blood (Capote was a crowd teaser as well as a crowd pleaser) that the book was heralded years before it was even finished. When In Cold Blood was serialized in The New Yorker, it was the closest thing the publishing world had seen to Beatlemania. The four issues broke the magazine's newsstand-sales record. The reviewers went hoarse with hyperbole. "He now broods with the austerity of a Greek or an Elizabethan," proclaimed Conrad Knickerbocker in The New York Times Book Review, though he didn't specify which Greek or Elizabethan. A notable dissent was Stanley Kauffmann's review in The New Republic, which deplored the compressed goo of Capote's Reddi-wip prose and contended that for all the book's heavyweight flexing it was psychologically slight and "residually shallow." It's a complaint echoed in T.C. by Norman Mailer. "I was unsatisfied when I read it. I thought, 'Oh, there we are again, that goddamn New Yorker, always ready to put a headlock on everything.'" But Kauffmann's and Mailer's astute gripes place them in the minority camp. Most readers, then and now, maintain an almost religious attachment to Capote's text.

The tumultuous success of In Cold I Blood was the making and breaking I of Capote. Some say that the shock of witnessing the executions left an existential hollow in his soul, others that all the fame and glory expanded an already swelled head. There's little doubt that certain tendencies in his character became more pronounced. His lying, for example. Like many writers, Capote had always been an embellisher, trying out things for effect; now his lies took on a brazen grandiosity. He claimed that everybody, male and female alike, found him irresistible. Albert Camus, Errol Flynn, Greta Garbo—all succumbed to his honeyed tongue. His friend Leonora Hornblow (now, there's a name) recalls, "He said he'd seduced Norman Mailer. My husband got up and went out of the room. . . . Norman Mailer? I wouldn't believe that if I saw it on this carpet!" Me neither, but it makes for a vivid picture. Capote devotee Joanne Carson (one of Johnny Carson's ex-wives) claims that Truman's lies were harmless fantasies—"In Truman's mind, he doesn't lie, he makes things the way they should have been"—but Gore Vidal takes a sterner, Montaignesque line, believing that Capote's lying was hostile and intended to harm others.

Accompanying the lying was an inflammation of snobbery. Capote, schooled in prissiness under Cecil Beaton, had come too far to consort with nonentities. The Black and White Ball was a lavish exercise in pomp and exclusivity, the delight being in deciding who made the cut. Leo Lerman: "One of the things he adored saying was 'Well, maybe you'll be invited and maybe you " won't.' " One of the Rashomon moments in T.C. comes from the conflicting testimonies of the glittering guests, some of whom thought the party never got off the ground and others who seemed to have spent the night blissfully levitating. Some outsiders (like firebrand Pete Hamill) thought it was in poor taste to conduct such opulent revels during the Vietnam War—it smacked of Marie Antoinette. The furor only heightened Capote's status as the little potentate of the ladies who lunch, making him "the most lionized writer since Voltaire, socially" (so sayeth the jewelry designer Kenneth Jay Lane). But at what cost to the quality of his brain? In his 60s diary, Edmund Wilson reports on a party starring Jacqueline Kennedy and Tennessee Williams at which "Truman Capote kissed all the ladies mushily with an 'Mm-mm-mm, Sarah,' etc." Multiply that a few thousand times and you're talking major sappiness. Babe Paley and Slim Keith may have been charm personified, but many of the rich twits he sought to amuse must have been studies in taxidermy. One of the comedies in both the Clarke and Plimpton books is the spectacle of Capote staying as a guest on his friends' yachts and being browbeaten to see historic ruins ("some big old bunch of fucking rocks," he complained). Culture bored him blind. He wasn't interested in the great works of the past but in the daisy chain of infidelities that made up the secret annals of society.

In Cold Blood brought Capote wealth and fame.^

ACT III

Answered Prayers was intended to be the ark that would survive Capote's lifetime and be his canonical legacy. For all his worldly success, he lacked full literary-establishment embrace. Incredible as it seems, In Cold Blood won neither the National Book Award nor the Pulitzer Prize. Both honors would go to Norman Mailer years later for The Armies of the Night, which infuriated Capote ("Norman Mailer, who told me that what I was doing with In Cold Blood was stupid and who then sits down and does a complete ripoff"), who grumbled about a "Jewish mafia" that had it in for him. Answered Prayers, its title taken from a possibly misattributed quotation from Saint Teresa of Avila ("More tears are shed over answered prayers than unanswered ones"), would be his masterpiece and silencer. It would have the sanctity of art, the dazzle of showmanship, the savage bite of an inside scoop. Only problem was, Capote was frozen at the console. Having compiled notes and spoken of the book since 1958, he conjured such a dense, shimmering mirage in his mind that the actual writing of the book seemed inadequate, like straining the Sahara through an hourglass. Deadlines to deliver the book came and went. Finally, in the mid-70s, he began to peddle portions of the unfinished novel to Esquire—a strategic gamble, since an adverse reaction can cripple a writer's morale.

The first glimpse, "Mojave," went over well. Then Capote gave Esquire "La Cote Basque, 1965," which would prove the blunder of his life. The chapter is a suite for voices, a cutthroat string quartet, narrated by Capote's protagonist P. B. Jones, a writer-masseur-male prostitute (busy, busy, busy), but dominated by his lunch date, Lady Ina Coolbirth, a coarse version of Slim Keith, with Carol Matthau and Gloria Vanderbilt eavesdropping at a nearby table and providing bitchy counterpoint. The dialogue about face-lifts and fat legs is serrated and overrehearsed, Capote's society swans sounding more like vultures picking over a carcass—"Shit served up on a gold dish," in the words of the art historian John Richardson. The set pieces within this set piece are two long anecdotes by Ina, the first involving the shotgun killing of her husband by Ann Hopkins (a thinly disguised Ann Woodward), an alleged murder that was ruled accidental; the second recounting an adulterous episode in which a powerful businessman beds a governor's wife, a "porco" with the mouth of "a dead and rotting whale," who "punishe[s] him for his Jewish presumption" by leaving his sheets sopping in menstrual blood. Unable to summon assistance, he spends frantic, sweat-drenched hours trying to scrub the blood from the sheets before his wife arrives home. Forget the misogyny that informs all of the unfinished Answered Prayers—that women are vulgar messes. The shock of recognition that rocked the Capote circle was that the cheating scrubber was clearly based on CBS boss William Paley, and the unsuspecting wife on Capote's longtime friend Babe Paley. He put filth into the mouth of one friend to slime the husband of another. As an act of betrayal, that counts as a twofer.

Speculation was that "La Cote Basque" was Capote's revenge for being treated as a court jester by his jet-set friends. However, court jester was a role Capote sought, not one he had clamped upon him; he prided himself on being able to "sing for his supper." And Capote didn't seem to realize he was playing with dynamite until he blew off his hands. When it was first broached with him that his friends might take offense, he said, "Nah, they're too dumb." Days before the issue hit the newsstand, Ann Woodward committed suicide, indicating that the import of the story wasn't lost on her. After Liz Smith did a cover article for New York magazine on the brouhaha, providing a scorecard to all the players, a caught-off-guard Capote tried desperate double-track diplomacy. Publicly, he not only defended the sacred right—nay, duty—of a writer to rat out those near and dear to him, but promised even juicier carvings to come. (A subsequent excerpt in Esquire featured Capote on the cover, fin_ gering what looked like a stiletto.) Privately, he funked. All my rich, idle friends have deserted me! Too old and obvious to make new rich, idle friends, he tried to patch things up with the former ones. He had his boyfriend, John O'Shea, phone Slim Keith as he listened on the extension. He wrote letters to Babe Paley. He professed his innocence to those who could serve as intermediaries. Running into Leonora Homblow, he asked, "Did you really think it was Babe? Did you really think it was Slim?" She replied, "Truman, come on," and quoted the line from Bom Yesterday, "Never crap a crapper." He had grace enough to laugh.

6 His ball was the Woodstock of the tuxedo brigade.^

During this crisis period, Capote said 11 to Diana Vreeland, "Oh, honey! It's U Proust! It's beautiful!" It was a line of defense seized by others at the time, that all literature is gossip, and didn't Proust leech off and tattle on his aristocratic coterie? Yet no sane person reads Remembrance of Things Past for tawdry tidbits on long-dead duchesses; its trance power derives from the opium jag of its reveries and perceptions. Gossip can be the germ for fiction, the initial trigger, but gossip shorn of any other purpose is belittling and petty. It reduces the complexities of character and motive into gotcha moments of shame and hypocrisy. In an essay on gossip that appeared in Clinical Studies: Inter- national Journal of Psychoanalysis, Sergio C. Staude observes that gossip serves a dual function—to spread a secret and to safeguard it by enlisting the listener as an accomplice. "[Gossip] will reveal something, but, following the rule of furtive dissemination, will prevent it from reaching the public. When it does, we are in another domain: that of news, of information, of the exhibitionist boast, that of treason or outrage." Cries of treason and outrage buffeted Capote, and as subsequent installments of Answered Prayers emerged, it became evident that he had no ulterior design to justify the gossip as social criticism or artistic license. He reported gossip without reimagining the participants. "Kate McCloud" featured cameo appearances by Tallulah Bankhead and Dorothy Parker as drunken bags; "Unspoiled Monsters" is littered with sneering references to lesbians ("pockmarked muffdiver" and "slit-slavering bitch") and score-settling shots at Ned Rorem ("a queer Quaker") and Arthur Koestler ("an aggressive runt"). Answered Prayers was probably bitched from the start, to use a phrase of Hemingway's, not only because Capote put his faith in the fool's gold of gossip and chose a narrative persona whose pissy attitude robbed the book of expressive range (it's hard to convey disillusionment through a hero-whore who sounds jaded from the get-go) but because his lyric gift couldn't withstand such elongation. As the writer Marguerite Young puts it in T.C., "Like many American writers, he existed in tidy vignettes of limited dimensions. . . . But just stringing them together doesn't make an epic. An epic has to have a vast undertow of music and momentum and theology."

It's possible that the publication of "La Cote Basque" was semi-deliberate selfsabotage—an unconscious act of suicide. Capote's mother, Nina, who longed to be accepted into cafe society, committed suicide by swallowing pills at the age of 48. Capote, who was accepted by society, may have harbored a resentment and self-loathing that compelled him to push the self-destruct button in a similar desire for oblivion (or a gesture of solidarity with his dead mother). For in detonating himself he precipitated a renewal of the very abandonment he had felt in his childhood and feared all his life would happen again. Even Lee Radziwill, treated kindly in "La Cote Basque," dumped him, refusing to intercede in a legal battle between him and Gore Vidal, telling Liz Smith, "Liz, what difference does it make? They're just a couple of fags." No one as canny as Capote could do something this convulsive without deeper forces at play. His weeping disbelief at the misery and havoc the story caused him and others suggests a profound psychological disconnect. The phrase "social death" has never been more apt. Capote killed himself off in the eyes of others and rolled downhill in a slow twilight of pills and drugs.

II is last days were comic horror. H Bereft, running on inertia, a social 11 lion turned social leper, he found refuge in the Los Angeles household of Joanne Carson, who kept a bedroom for him which later became a kitschy shrine. She mommied him in his hour of need; she created a protective bubble and kept the bad people away. "When Truman was here, I put my answer phone on and I was not available to anybody, because my time was so precious." They drove to Malibu and flew kites— kites are a recurring motif in Capote's fiction— or took imaginary trips together. Joanne Carson:

6 Capote was both the snake charmer and the snaked

He'd call me from New York and say, "Tomorrow we're going to Paris." I would pick him up at the airport; we would come home, I would put my answer phone on, and cancel anything I had for the next day, and when I would wake up in the morning he would bring in a tray with croissants and sugar cubes from the Ritz Hotel and little jars of marmalade from the Hotel Crillon, which of course he'd lifted. Then we'd take out books from the Rodin Museum, books from the Louvre, and we'd take a trip there. "Now we're going to have lunch," he'd say; he'd pick a restaurant and we'd have a French-style cuisine here to match, and so we would spend a whole day in Paris without moving. We did the same thing with China. We went to Spain; we went to Mexico.

All without ever leaving the house. Doesn't it sound charming? Doesn't it sound insane?

On Saturday, August 25, 1984, Capote expired at Carson's house, though one comedienne wickedly speculated that he had died on the lawn and she dragged him indoors. His funeral would have made a fitting sequel to Evelyn Waugh's The Loved One. The service was held at noon at the Westwood Mortuary on a day so hellish you can practically hear a giant fly buzzing on the soundtrack. Robert Blake, who costarred in In Cold Blood but was more famous as the streetwise cop in Baretta, babbled in actorspeak about himself. The bandleader Artie Shaw went off on an endless tangent about Duke Ellington's funeral. Joan Didion: "We were watching and suddenly a glaze came over Artie's face and he realized he was far afield. So he got a grip on himself, and he said, 'And many of the same lessons apply. These were some of the same thoughts that were in my mind today!'" Didion's husband, John Gregory Dunne: "This thing was a fucking nightmare. Absolute nightmare. Then Joanne Carson got up with great rivulets of mascara coming down, like a couple of rivers, and she read from one of the stories, gulping away like people who can't control their tears." The last speaker was Christopher Isherwood, who said that the wonderful thing about Truman was that he had always made him laugh, a remark that some found winning and others (the Rashomon effect again) found coy. In the latter camp was Carol Matthau, who told Plimpton, "He said, 'Everytime I think of Truman, I laugh.' And he laughed and laughed. I think he was tinkling in his pants. It was a debacle."

Capote's divided nature followed him into beyond death. According to Joanne Carson, his wish was to be cremated and have "half of his ashes kept in Los Angeles and half in New York, so he could continue to be bicoastal." Truman Capote—terminally chic.

EPILOGUE

But let's not end on a snotty note. Alii though he's been dead more than a If decade, Truman Capote doesn't seem a dated figure, unlike so many writers of his generation (James Jones and Irwin Shaw, to name two). His iridescence has kept his reputation alive. Capote had a tabloid mentality with a slick-magazine gloss, which made him one of the most representative writers of his (and our) time, a roving ambassador between the last remnants of the Beautiful People and the celebrity photon chamber of People magazine, where new famous nobodies are covered weekly. Like Andy Warhol, whom he worked with at Interview, he understood that in the media universe real fame and bogus fame occupy the same lustrous plane, or at least adjoining booths on The Hollywood Squares. Capote's tragedy was that he came to value the spoken word over the written word, believing that he could sweet-talk his way out of anything because he had sweettalked his way in. He was both the snake charmer and the snake, toying with toxic insinuation until the spell snapped and he was bitten by his own sound bites. In a chapter of T.C. called "In Which the Reader Is Let In on TC's Secret," we learn that Capote kept a small studio apartment where he maintained a collection of snakebite kits, which he decorated with collages and cryptic phrases, like Joseph Cornell boxes. It was his private stash of voodoo, an attempt (like his fiction) to make something lasting and celestial out of loneliness, menace, and fear. I bet they're beautiful.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now