Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

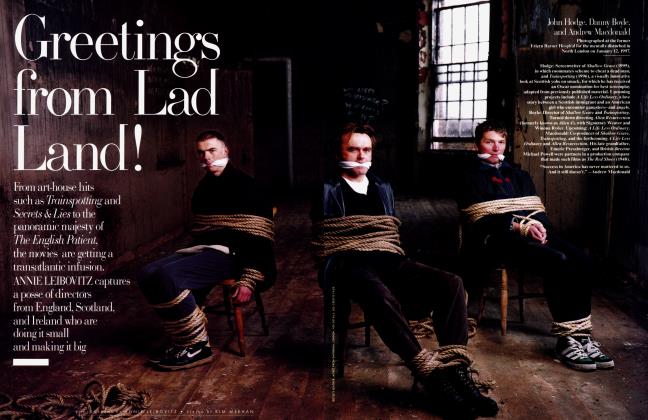

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHBO has an impressive record of cult hits among the smart set, but The Sopranos, its darkly comic series about a modern Mafia family, is the classiest TV phenomenon in years. A sneak peek at the new season underlines why it’s a show you can’t refuse

February 2000 James WolcottHBO has an impressive record of cult hits among the smart set, but The Sopranos, its darkly comic series about a modern Mafia family, is the classiest TV phenomenon in years. A sneak peek at the new season underlines why it’s a show you can’t refuse

February 2000 James WolcottIn Hollywood’s gala youth, when blackand-white films had the gleam of piano keys and no man or woman was safe from the jaws of Joan Crawford, movie studios boasted distinct styles and identities. Decades before “branding” became a buzzword, studio chiefs recognized the importance of differentiation, carving out niches that evolved into house specials. An MGM musical, a Warner Bros, crime saga, a Paramount comedy, a Universal horror film—each make and model had its own familiar faces, wardrobe touches, editing rhythms, and, if you’ll pardon the French, mise en scene. (Manny Farber, writing about the director Raoul Walsh,

noted the peculiar oppression of “the allpurpose Warners backlot” with its “mysterious, all-white, slanted abutments, which could be a brewery, Nazi munitions factory, chemical plant, or penitentiary wall.”) With the demise of the studio system, Hollywood back lots changed from dream factories into expensive launchpads, each payload having its own roster of egos and agendas. No longer able to maintain the continuity of contract players, the personal stamp of a mogul’s meaty thumbprint, or the guild stagecraft that gave genre films their organic form (who makes musicals anymore? who would know how?), movie studios have lost their identity; they now

stand for nothing except their shareholders’ interests. The closest echo of the Hollywood studio of old is cable’s Home Box Office (HBO), which has fashioned a varied persona, and a full menu to match. It’s its own multiplex.

HBO’s variety pack consists of prestige original productions such as RKO 281, A Bright Shining Lie, and Witness Protection; comedies with attitude, ranging from the mouthy talk shows hosted by Chris Rock and Dennis Miller to Robert Schimmel’s rauncharama stand-up routine and Larry David’s pseudo-documentary “comeback” quest; risque slapstick farces such as Dream On (a Walter Mitty-ish fantasy which

found Brian Benben pogo-ing with a different set of bouncing boobs each week) and the popular Sex and the City, about four swinging bachelorettes with easy-drop panties (this season even the show’s “good girl,” Kristin Davis’s Charlotte, went slutso) who mimic a bubbly manner as they trade quips about what cads men be; voyeurvision series such as Taxicab Confessions and Real Sex, those anthropological video studies of perverts (and I

Unlike the broadcast networks, HBO has to please only its upscale subscribers.

mean that in a caring, nonjudgmental way); showbiz satires such as Robert Wuhl’s Arli$$,

Tracey Ullman’s Tracey Takes On , and The Larry Sanders Show, starring Garry Shandling, who raised Lettermanesque queasiness to an existential pucker as he anxiously ventured down the corridor, hoping in vain to avoid human contact; and serial dramas such as the prison opus Oz and The Sopranos. Under the leadership of Michael Fuchs and his successor, Jeff Bewkes, HBO has created a pungent hybrid of movies and television. Unlike the broadcast networks, which rely on advertising and are obsessed with demographics (how do we entice the kiddies?), HBO has to please only its upscale subscribers. The prime directive of HBO programming seems to be to use this license to go farther out and/or deeper in than the competition—to knock down the safety rails of what’s expected and permissible. (Other pay-cable outfits, such as Showtime, are playing catch-up, but

the latter’s original series— Rude Awakening, starring Sherilyn Fenn as a recovering alcoholic, and Beggars and Choosers, a toothless Larry Sanders copycat—suffer from a lazy reliance on four-letter words and rampant name-dropping.)

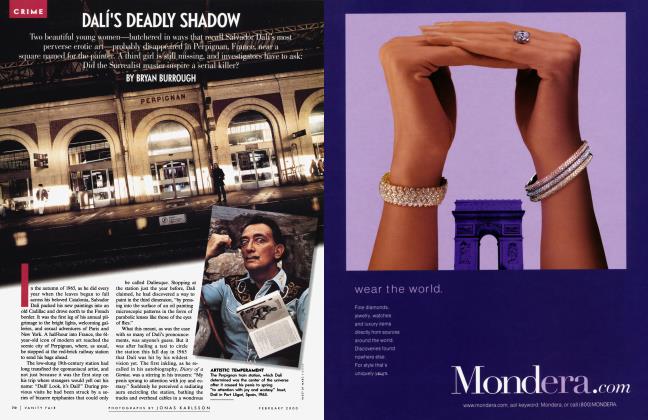

ver the years HBO has had its cult hits among the smart set. Before The Larry Sanders Show there was Robert Altman and Garry Trudeau’s Tanner ’88, which jumbled real politicians with actors pretending to be politicians, turning the 1988 presidential campaign into the first postmodern election (and used mirror and prismatic reflections to convey the fracturing of reality in the media age—imagine, an aesthetic device! on TV!). But the network has never had a sensation to compare with The Sopranos. Debuting in 1999 and twice repeated, the show’s initial 13-episode run ingrained itself so quickly and forcefully on the public imagination that it seems to have filled a dormant slot we didn’t know existed, much as The X-Files did. It came looming out of the collective unconscious and took possession of the living room. Created by David Chase, who wrote and directed the show’s premiere (and whose

fine credits—The Rockford Files, Northern Exposure—gave little inkling of the weird corners he was preparing to turn), The Sopranos is set in New Jersey suburbs lying beyond the graffiti reach of urban rot. The show’s depiction of the suburbs is refreshingly snob-free. It doesn’t stigmatize suburbia as an isolated panel of Norman Rockwell Americana slowly being eaten away by the acid drip of bourgeois alienation (as films such as The Ice Storm and Happiness did) but portrays it as an oasis requiring constant upkeep. Some of the show’s best scenes are conscientiously observed suburban rites and activities—high-school pageants, backyard barbecues, soccer practice—where the surface normalcy offers the false reassurance that the center still holds. It’s as if the show’s sleaze factor was told to wait in the car.

Suffering from depression and a midlife crisis that has him lumbering through the house in a bathrobe as if bitten by a tsetse fly, Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) is a mobster—sorry, waste-management consultant—whose upward mobility has undermined his primate status. He can’t bust thick skulls with the same stone-cold brio anymore. He has bad dreams, panic attacks, fainting spells. The sight of a family of ducks stopping at his swimming pool during migration fills him with the inexplicable melancholy of a John Cheever character attending to dusk. Although it violates every unwritten rule of being a made man, he visits a psychiatrist (Lorraine Bracco) to confide his mortality fears and bemoan the fact that every moocher in the tri-state area is on his case. His wife, Carmela (Edie Falco), is wise to his antics with whores. His own kids spout off at him: “So what, no fuckin’ ziti now?” His mother, Livia (Nancy Marchand), consigned to a rest home, wants him dead. Ditto his Uncle Junior (Dominic Chianese), a baldy who resembles an angry tortoise and whose lips are always pursed with distaste. Put on Prozac, Tony sleepwalks through the day behind drawn curtains, his vulnerable condition making him an even juicier target for his enemies. In the American prosperity of the 90s, indicates The Sopranos, even our gangsters have gone soft. (John Gotti, languishing in solitary, is the last hard man.)

With its genuflections to Martin Scorsese’s GoodFellas and Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather films, The Sopranos extends the tale of Italian-American crime from the immigrant storefronts and

private clubs of Little Italy to the latte bars of suburban malls, hauling a mythical storage unit filled with old Jerry Vale records, black-velvet paintings, and shrines to the Virgin Mary. Critic Pauline Kael, a fan of the show, cites Prizzi’s Honor as another source for its comic mayhem. The show The Sopranos most reminds me of is Wiseguy, a CBS series created by the prolific Stephen J. Cannell (The ATeam, etc.), starring Ken Wahl as undercover agent Vinnie Terranova, playing dumb under a handsome-caveman brow. Broadcast from 1987 through 1990, Wiseguy broke with the standard format of self-contained episodes and pioneered the development of the extended story arc; each undercover assignment was a separate odyssey—an initiation into a David Mamet-ish squad room of shifting loyalties, opaque motives, and coded language. Not compelled to cut to commercial at the end of every dramatic beat, as Wiseguy was, The Sopranos has an even deeper, murkier flu-

idity; its paranoia is a richer brew.

Another correspondence between the two series is the latitude accorded the actors. Few network series let actors wig out more than Wiseguy did. The late Ray Sharkey did his greatest work there as a hepcat hood; the series introduced audiences to Kevin Spacey, riffing brilliantly as a deranged visionary named Mel Profitt whose “reality-distortion field” rivaled Steve Jobs’s; and Jerry Lewis, a man in full, bore the crumbling-pillar resignation of an Arthur Miller hero in his role as a besieged merchant in the Garment District. More of an ensemble show, The Sopranos is equally actor-centric. Had it been sold as a network series, James Gandolfini probably never would have been picked for the lead; he’s too beefy and lacks sufficient follicles. Here, he has ample room to treat his body like a comfortable chair when he is in repose and mobilize into a butterball of vengeance when

the situation demands. On a network series the supporting cast would have been gift-selected from the latest crop of scrubbed faces vying to be the next Dawson or Felicity. The Sopranos doesn’t hesitate to hire actors who look as if they fell out of the back of a van. From top to bottom, the lineup card of The Sopranos crackles with the creative friction of actors—fledglings and experienced pros alike—being allowed to angle their characters against the usual norm and not be confined to excreting a single, pellet-size point per scene.

The women especially. Aside from Anjelica Huston in Prizzi’s Honor, who could leg-wrestle an alligator if it came to that, women in Mob movies tend to be either nightclub bimbos decked out in acrylic hair

The sexual parity in the acting and dialogue helps widen The Sopranos beyond the "guy" ghetto.

and Christmas-tree-ornament jewelry—Rat Pack chicklets—or troubled spouses minding the fort as the menfolk are off playing cards or stuffing former associates into trunks. Women are seldom the activators. Taking a cue from the BBC adaptation of I, Claudius, where Sian Phillips’s Livia was the evil matriarch poisoning half the upper ranks of the Roman Empire and scorning her emperor grandson as a hopeless simpleton, The Sopranos has its own batch of soured mother’s milk in Nancy Marchand’s Livia, the stroke-victim droop of her face concealing a steel-trap cunning. Those of us who know Nancy Marchand

best as Mrs. Pynchon, the Katharine Graham-like class-act newspaper owner on Lou Grant, can only marvel at her transformation into a crone cawing at everyone around her in a voice that’s the aural equivalent of lead paint. Her entire existence is a bitter reprimand and a rehearsal for martyrdom. (One of the comic highlights of the first season was the smile on Tony’s face as he swiped a pillow on the way to her hospital bed, savoring the prospect of smothering her.) If Livia is a fairy-tale evil godmother, Edie Falco’s Carmela appears to embody the reality principle; her self-validation seems shatterproof. When Michelle Pfeiffer played a Mafia wife in Married to the Mob, she was feisty and enjoyable but engaged in an obvious impersonation—she got points from the critics for shedding her blondness and tawking like dis. Falco’s performance is completely unfabricated. Her Carmela is all there, hip-propelled as she makes her daily rounds, her preening gestures revealing a host of small prides and her eyes utterly unfooled by the lies Tony tells as he clomps upstairs to hibernate. (“What am I, an idiot?”) Perhaps the sharpest exchange on television last season was the one in which Carmela told off Father Phil (Paul Schulze), a New Agey priest who had been flirting with her and partaking of her baked goods, the little coquette. She set him straight with such tender finality and analytical acuity that it was like a ruling from a higher court, delivered like rain. It was one of those rare moments on TV when conversational dialogue did the dramatic work usually accorded to rhetorical grandstanding. The sexual parity in the show’s acting and dialogue helps widen The Sopranos beyond the “guy” ghetto.

The show is also progressive in another cockeyed way. Crime shows such as The Sopranos, Law & Order, and NYPD Blue are the only places where ethnic tensions can be vocalized and bruited about without a lot of nervous throat clearing and assurances of good faith. The urgency of the situations and the collision force of the street mentalities in one another’s faces cut down on Bill Moyers mind-meld empathizing. Although some notables in the Italian community have complained about the show’s stereotypes (their protests proved short-lived when Rudy Giuliani, among others, rallied to the show’s defense), The Sopranos spreads the ethnic slurs fairly evenly (“Yo, hairnet central ... ”), practicing its own, pirate

version of multiculturalism. Backing a stolen U-Haul up to the American Dream, The Sopranos says that regardless of one’s skin color, religious faith, or ethnic heritage, we are subject to the same itches; pious Jew, uptight Wasp, guilt-ridden Catholic, barrio brother, gold-toothed hiphopper in wide-load pants, we are all basically greedy, horny bastards underneath. Our scoring opportunities are what allow us to put aside petty differences and divvy up the booty. (“Booty” in both senses of the word: a Hasidic desk clerk, being bribed to look the other way as tricks are turned in the hotel rooms, receives his payoffs from the lips of a black hooker.) Business is business, just don’t move in next door, capisce? I catch you on the lawn, you’re dead.

The second season of The Sopranos, which begins on January 16, inevitably gives rise to second thoughts. Is the show really that good? Is it truly an angstdriven artwork that deserves to be ranked with Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz and Dennis Potter’s The Singing Detective, as Vincent Canby proposed in The New York Times'? Or is it another example of American autohype, like the Ally McBeal craze? Even those who side with the majority opinion might blink at Canby’s assertion that The Sopranos “possesses a tragic conscience.” That dark the

series doesn’t go. It gets off too much on the stompings meted out to those who cross Tony and his crew (especially his overachiever nephew, played by Michael Imperioli, a punk-ass junior Mussolini who tattoos his heels into his enemies’ ribs), and on the dumbo arguments these bruisers have when they’re wasting time together. Like Martin Scorsese with his goodfellas, the writers of The Sopranos can’t hide a sneaky admiration for balls-for-brains primitives who don’t censor their words or actions, who have no interest in controlling what Tony’s shrink might label their “impulsivity.” Sociopaths who look as if they just stepped out of the barber’s chair, these wiseguys seize life and squeeze it till it pops, an experience denied us more introspective types with our magazine subscriptions. The only one afflicted with a conscience and the ability to think beyond his next meal is Gandolfini’s Tony, who earns the audience’s sympathy for having a soft, chewy center and being, despite everything, a family man—a dedicated provider. Tony is a monster, but a witty monster with whom the series makes it too easy for us to identify. The shrink sessions, which tend to

be the weakest links in the show (Lorraine Bracco’s psychobabble sounds memorized, like a poem being recited at show-andtell), contain elements of special pleading, as if Tony’s soul-sickness absolves him of moral responsibility for his actions. In real life, hoods like him would have zero conscience and barely traceable charm.

■■ ortunately, real life and top-rate enterla tainment have only a passing resemI blance to each other, and I can report that whatever one’s qualms about the show’s gangster chic, there’s no sign of quality drop-off in season two. After being rolled into a blanket and carried like a giant Tootsie Roll into an undisclosed screening room in Manhattan, I was able to take a hush-hush peek at a new episode to be shown in February, featuring a cameo appearance by Frank Sinatra Jr. (teased in the show as “Chairboy of the Board,” he displays a winning comportment and authority). Frank junior and the director Paul Mazursky are among the guests playing cards in a high-stakes showdown called “the executive game.” Hosting and catering it is an honor and a privilege for Tony, who maintains his aplomb even when a tightly wound Silvio (Steven Van Zandt) excoriates

These wiseguys seize life and squeeze it till it pops.

one of the help for being a “cheese fuck.” Elbowing a place at the table is a sporting-goodsstore owner played by Robert Patrick (Termina-

tor 2), a “Jew gentleman” who’s in over his head and an incident waiting to happen. Even when he’s in the hole to Tony for serious G’s, he thinks they can go off and have a shvitz together. (Tony is forced to dole out his own form of physical therapy.)

The marathon card game provides the narrative hub around which the story line’s continuing developments revolve like spokes. Out of his bathrobe, Tony is still in his funk. “I got the world by the balls

and I can’t help feeling like a fuckin’ loser,” he informs his shrink. The big picture is no better. We used to be a country of strong, silent types, he laments, now we’re “a nation of pussies.” (When she tries to pacify him with some pearl of wisdom from Carlos Casteneda, he snaps, “Who the fuck listens to prizefighters?”) In another scene, Tony learns that he has a mentally slow uncle whose existence has been hidden from him all these years. “My mother would argue about my father’s feebleminded brother, but I always thought she meant you,” he tells Uncle Junior, who’s under house arrest and in no mood for mirth. He’s also dogged by his wraithlike mother, who wails at a funeral service for one of the clan. (“Fuckin’ Bette Davis back there,” he mutters.) At the end of the episode Tony and Carmela undergo an ordeal that even the Corleones didn’t have to endure: listening to daughter Meadow (Jaime Lynn Sigler) perform the theme song from Titanic on high-school cabaret night. They can’t pack that kid off to college fast enough.

Aside from the mild roughing-up of Robert Patrick’s bad-credit character, the violence in this Sopranos was minimal, which was a relief. The psychological hexes being cast are more intriguing than beatings and the indiscriminate use of steak knives. Like a magician plucking silk handkerchiefs from his sleeve, The Sopranos seems to have a limitless supply of surprises to flaunt, fanning out in different directions and pacing itself to its own points of emphasis rather than bowing to the pressure of trying to top itself. When you see a movie like Bringing Out the Dead, you can sense how determined Martin Scorsese is to dazzle Hollywood with an adrenaline rush of money shots to show he can hold the wandering eye of today’s antsy audiences. The film’s hyperactivity reflects the EKG of a genius director under the gun to prove himself all over again. The noncommercial structure of HBO helps insulate creative talent from the warp effects of huge budgets and crushing career expectations. Just nominated for five Golden Globe Awards, The Sopranos swims with the playful purpose of a group effort that hasn’t been script-conferenced or focusgrouped to death. They’re having fun at a profound level. What lifts HBO above the competition is that when it gets hold of a great property like The Larry Sanders Show or The Sopranos it resists the temptation to tinker (i.e., ruin things). That’s so rare these days, it’s practically Utopian. Now, if only HBO would stop foisting Arli$$ on us ...

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now