Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

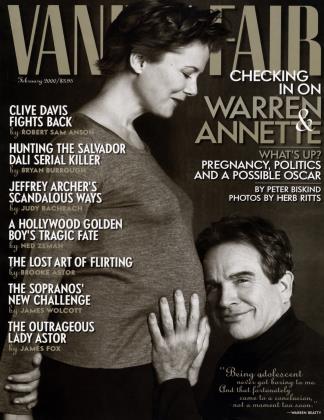

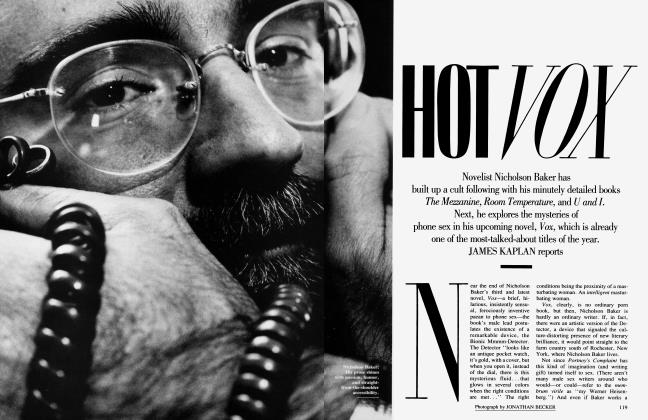

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowForthcoming from the Warren Beatty-Annette Bening household: his next movie, Town and Country with Goldie Hawn, Diane Keaton, and Garry Shandling: her new movie, Mike Nichols's What Planet Are You From? also with Shandling and the couple's fourth child. Not to mention Beatty's recent foray into presidential politics and Bening's Oscar worthy rolein American Beauty; Together and apart, Hollywood's most powerful star team give PETER BISKIND the lowdown on fame and family, thier takes on Bill and Hillary Clinton, and a wonderfully indiscreet account of thier first time together

February 2000Forthcoming from the Warren Beatty-Annette Bening household: his next movie, Town and Country with Goldie Hawn, Diane Keaton, and Garry Shandling: her new movie, Mike Nichols's What Planet Are You From? also with Shandling and the couple's fourth child. Not to mention Beatty's recent foray into presidential politics and Bening's Oscar worthy rolein American Beauty; Together and apart, Hollywood's most powerful star team give PETER BISKIND the lowdown on fame and family, thier takes on Bill and Hillary Clinton, and a wonderfully indiscreet account of thier first time together

February 2000"Her agent thought I was just going to make a pass at her.... And it turned out he was right."

Warren Beatty has always been careful about what he puts in his mouth. In the decade or so that I’ve known him, I’ve never seen him consume anything gastronomically incorrect—take a drink, eat a piece of meat, a dessert, even a bite of cheese. But now we’re in a small, quiet Los Angeles restaurant called Four Oaks near the bottom of Beverly Glen, eating dinner on a balmy evening in late November, just after Thanksgiving, and he’s eyeing a small, pasty disk in the middle of his wife’s plate.

“What is it?” he asks Annette Bening, as if he’s never seen anything like it before.

“Goat cheese,” she replies. As I look on with amazement, in the knowledge that nothing Beatty does is without significance, he considers, reaches over with his fork, and says, “I think I’ll try some.”

“Good! Live it up, Warren,” his wife responds.

Marriage has transformed Beatty, who speaks of his life as falling into two parts, “Before Annette” and “With Annette.” He elaborates, “When I was in my 20s and 30s, there were certain things that were irresistible.” Pause. “And then into my 40s.” He laughs, and pauses again. “And into my 50s. Being adolescent never got boring to me. And that fortunately came to a conclusion, not a moment too soon. I stood a good chance of reaching the end of my days as a solitary, eccentric ... fool.”

This week seems like a moment of downtime for the couple. Beatty’s undeclared non-run at the presidency is winding down, if that’s not a contradiction in terms for an operation that was so low-key from the start, conducted mostly by others in his name, sometimes with his blessing, sometimes not. In fact, “operation,” with its implication of directed activity, is not quite accurate, either, to describe whatever it was that happened last August, the “floating” of his name by Arianna Huffington in a newspaper column, which now seems to the careless eye no more substantial than a beach ball bobbing in the summer surf. But, as Mike Nichols observes, “Warren is full of surprises.” This is the first interview the actor has granted since he declined to discourage speculation about his interest in the presidency.

Things are due to heat up soon. There’s Beatty’s new film, Town and Country, directed by Peter Chelsom, which also features Goldie Hawn, Diane Keaton, and Garry Shandling, as well as a sparkling array of other actors. Bening, too, has a new picture, a romantic comedy called What Planet Are You From?—written by and also starring Shandling (a close friend of the couple’s) and directed by Nichols—due to arrive in March. And then there’s the likelihood that Bening will get an Academy Award nomination, following her Golden Globe nomination, for her spectacular turn as Carolyn Burnham in American Beauty, which would put her up for an Oscar right around the time she expects to give birth to their fourth child.

SCENE FROM A MARRIAGE: Beatty and Bening famously failed to meet—a ships-passing-in-the-night sort of thing—when he was casting Dick Tracy in 1988. He canceled a meeting, she canceled a meeting. He had already developed a certain interest in her: “I had heard about Annette, and you know, you have opinions of certain people’s opinions.” When they finally got together in 1991, it was at Santo Pietro, a restaurant in the Beverly Glen Center, a mini-mall near his office. He was casting the Virginia Hill role in Bugsy. Barry Levinson, who directed the picture, and James Toback, who wrote the screenplay, were thinking about Michelle Pfeiffer. But Beatty, who was seeing several women at the time, told them, “No, I think Annette Bening would be perfect. I’m having lunch with her tomorrow.”

Beatty, Bening, and I are now sitting in a restaurant at the same Beverly Glen Center, a third of the way down the hill from Mulholland Drive, where the couple has a home. The two of them are reminiscing about the way they were. “Her agent didn’t want me to meet her because he thought I was just going to ... make a pass at her,” Beatty recalls. Bening corrects him: “Well, what he said was—”

“And it turned out he was right.” Beatty laughs.

“What he said was ‘He’s meeting every actress in Hollywood.’”

“How long did it take for you to realize that Annette was the one?,” I wonder out loud.

“It took about ... 10 minutes. Maybe five. And ... I felt very conflicted because I was so elated to meet her, and yet at the same time, I began to mourn the passing of a way of life. I thought, Oh, everything’s going to be different.”

“We walked up and down the cul-de-sac,” Bening says, breaking in.

“Behind my office. She talked about her family.”

“I remember you talking a lot.”

“Well, that was the problem, because I went into peacock syndrome. And couldn’t shut up. I did everything but stand up and do a soft-shoe on the table. And then I went upstairs to my office, and Jim Toback was there in the cutting room placing bets.

He said, ‘What did you think?’ And I said, ‘Whoa!’” (As Toback would tell me later, “It was very clear who would get the part.”)

I ask them a tactless question about the progress of their courtship.

Beatty: “I said to Annette that, as much as I was inclined to make a vulgar move upon her, that I would refrain from doing so because I thought it was terrible when people had to work together, if they had that pressure ... and so I wouldn’t be troubling her with that.”

“Go ahead,” Bening says, rolling her eyes, “but I don’t want to hear this.”

“It got to be late in the movie, and her mother and father came to visit the set. I invited them into my trailer for lunch. I thought, What nice people. And this is an actress ... an actress who’s human, whose mother and father seem to be very, very good people, of good humor, who have been married for ... ”

“Forty-some years at that point.”

“As they were leaving, I took Annette aside and said, ‘I want to tell you that I’m not making a pass at you, but if I were to be so lucky as to have that occurrence happen, that I want to assure you that I would try to make you pregnant immediately.”’

I am beginning to suspect he’s drunk on green tea.

“Am I being indiscreet?,” Beatty asks his wife.

“No, I mean ... I don’t know. This is all very precious to me, obviously. It’s ... we’ve never said it before.”

“Well, let me put this in a way that I think no one will understand it. I finally said, ‘You know, we have one more scene to do in the movie before the picture’s wrapped up, and maybe if we went to dinner it wouldn’t be so much pressure on either of us,’ and I asked Annette if she wanted to have a child. After a few minutes she said she did. And I said, ‘Well, I would like to do that right away.’ And we did.”

“You got pregnant that night?,” I ask.

“Umm ... very quickly,” replies Bening. “Because we were ... trying.”

“There was never a moment of not, in effect, being married to Annette.”

“So ... that’s the truth. And that’s a nice thing for our kids to know.”

“No one knew that we were involved with each other,” Beatty goes on. “I had brought my mother out to California because she had had some little strokes and things. She was really declining, in and out of compos mentis-dom, and I thought, Even though we haven’t told anyone else that we’re going to have this baby, I want to tell my mother. I figured she would forget it in another five minutes. So I said, ‘Mother, Annette and I are going to have a baby.’ She said, ‘Oh, that’s wonderful.’”

A week or so later, Beatty inquired of the woman who was taking care of her, “How’s my mother today?” The nurse responded, “Your mother’s not in very good shape,” implying that she had completely lost it. “Why?,” Beatty asked. “She thinks you’re having a baby.”

The couple named the baby Kathlyn, after Beatty’s mother.

AMERICAN BEAUTY: Bening shares her husband’s politics, especially his antipathy for the Clinton administration’s policies. With her sandy hair cut short, gamine-style, she is dressed casually in layers of shirts, a scarf, Chinese silk pants, and flip-flops, in the chill of the late-autumn afternoon. She sits on the terrace of the Chateau Marmont in Hollywood and talks about Hillary Clinton, whom she has met on several occasions. When she first heard her speak, on health care, she was “knocked out. Mrs. Clinton told a story about a child who was ill. I was moved to tears. [But later], if I showed up at an event, she would make sure that I was brought up and that she had time to see me. I saw how politically deft she was, and I was not completely seduced by that. And then there’s my disappointment over the administration, how they’ve ended up. I have a lot of mixed feelings about what she’s doing now [running for the Senate]. She always appears to be doing what’s politically expedient in the most transparent way. That whole thing about the clemency with the Puerto Rican terrorists and how she claimed that she hadn’t spoken to him about it, that was an example to me of just how you feel like there’s prevaricating, there’s lying. You just don’t trust them.”

Born in 1958, Bening more or less missed the 60s, was in high school when the Vietnam War had devolved into waiting for the Vietcong to descend on Saigon. It wasn’t until she was at San Diego Mesa College and taking her first women’s-studies course that she started to develop a political consciousness. “I am still reluctant to use my celebrity, to just show up at a place and draw attention to a given issue like abortion rights or Amnesty International,” she continues. “Part of it is time with my kids, and if I’m not working, I’m just basically doing them.”

So far, the children’s heads have not been turned by growing up in the eye of the celebrity hurricane. Isabel, two, is too young; Ben, five, is more interested in baseball than movies; and Kathlyn, seven, is a Harry Potter fan and voracious reader who once dismissed Dick Tracy as “silly.” Still, the annals of Hollywood are full of movie stars’ kids gone wrong, and Bening and Beatty have given a lot of thought to how best to raise theirs. “Neither of us were raised wealthy, so we don’t have an instinctive understanding of what that is like for a kid,” reflects Bening. “We go to a five-year-old’s birthday party, and it’s a carnival on the tennis court. Considerably out of proportion from what’s appropriate, from my point of view. So I don’t do that. If anything, I’ll probably overcompensate. They have to do their own chores. They have to earn what they get. The good part for us, at least, is that we both work really hard and they see that.”

Bening isn’t kidding when she says they both work hard. She went from American Beauty to a stage production of Hedda Gabler at the Geffen Playhouse in Los Angeles (for which she got generally very good reviews) to What Planet Are You From? without a break. The new movie is a romantic comedy about an alien bent on world domination (played by Shandling) who comes to Earth to impregnate a woman. Of course, he falls in love with Bening’s character, and the story turns out essentially to be about men and women wanting different things of one another, about women humanizing men, perhaps an antic version of Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus, or, in this case, Earth. The pleasure in it is how you get there, a journey that is, needless to say, very funny. The story bears a passing resemblance to the Beatty-Bening romance, and for a minute I thought Shandling was having some fun at his friends’ expense. Nichols, however, dismisses this scenario. “Oh no,” he says. “That would have meant that Garry had to think about somebody else, which I think is difficult for him.”

Bening’s due date and the Oscars are uncomfortably close together. She doesn’t want to talk about being nominated, doesn’t want to “go there.” I wonder if she’s allowed herself to think about what it would feel like if she’s nominated and has to spend Oscar night in the maternity ward. “What’s more important?” she asks, smiling. Then she laughs. “Oh, God, it would be hilarious.” But delaying the birth date, even if it were possible, is the last thing on her mind. “At the end of the pregnancy, you are so filled with hate and bitterness and rage—at least I am—that all you want is to get it out,” she says. “It never occurs to you to say, ‘Oh, gee, if only I could stay pregnant another few weeks.’”

BULWORTH DEMOCRACY: A lifelong Democrat, Beatty has been actively, if fitfully, involved in campaigning at least since Robert Kennedy’s run for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1968. His first vote was cast for John F. Kennedy in 1960, and he was instantly drawn to the galaxy of politicians and celebrities that swirled around J.F.K. A year later Beatty himself became a star with the release of Elia Kazan’s Splendor in the Grass, and soon filmmakers were looking at him as a bridge between Hollywood and Washington. When Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, a stinging send-up of the kind of Cold War saber rattling that had taken Kennedy to the White House, was on the verge of release, and the director was worried that Kennedy would try to block the picture, he asked Beatty to arrange a screening for administration officials. He did. They thought it was funny.

"Warren never promoted himself as being this beacon of hope that everybody wanted him to be.”

When Kennedy was gunned down in Dealey Plaza on November 22, 1963, Beatty was at Kubrick’s apartment on Central Park West trying to persuade him to direct What’s New Pussycat?, a project the actor was developing with the legendary agent turned producer Charlie Feldman. Kubrick passed on the film. “Stanley was always mildly amused by what I felt was funny,” says Beatty. As he was leaving Kubrick’s building he heard a radio bulletin from Dallas in the lobby. He got into a cab and went across the park to Feldman’s place on East 68th Street for a meeting with Woody Allen, whom they had hired to do a rewrite of What’s New Pussycat? Beatty recalls, “We all sat there, stunned.”

Beatty’s interest in politics only grew. He argues that, because of the Vietnam War, Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society was still-born. “This was the great tragedy of the past 45 years,” he says, “because it did much harm to a way of thinking which people began to call ‘bleeding-heart liberalism,’ ‘big government stupidly throwing money at problems.’” When Bobby Kennedy came out against the Vietnam War in 1968 and declared his candidacy, Beatty jumped on board. “I didn’t want, as Cary Grant put it, to spend my life just tripping over cables on soundstages. Bobby was one of those few people who was completely accepted by the Establishment who still wanted to rattle the Establishment,” he says, offering a characterization that could apply equally to himself.

Beatty attended the Democratic convention in Chicago in 1968, which nominated Hubert Humphrey. He was teargassed in the park across from the Hilton Hotel, where Humphrey was staying. “I looked at my watch and said, ‘It’s 10:45. I really must be going, because I have a meeting with Hubert.’ So I crossed the street and went into the Hilton. Hubert, who I always liked a lot, wanted me—Bonnie and Clyde was now a big hit—to be part of a campaign documentary. I said, ‘Absolutely I will. But you have to break with the administration on Vietnam, which I assume you’re going to do.’ And he said, ‘Don’t worry, that’ll be happening within the next week and a half.’ And, of course, it didn’t happen.”

Four years later, Beatty worked hard for George McGovern’s candidacy. According to Ronald Brownstein’s excellent study of Hollywood and Washington, The Power and the Glitter, he knocked on doors, introduced McGovern at rallies, spoke on campuses, in living rooms and union halls. Ironically, given his current feelings on the subject, Beatty became celebrated for his gutsy fund-raising. Democratic pollster turned producer Pat Caddell tells about the time Beatty strong-armed a fat cat in Cleveland to contribute to McGovern. The man wrote a check for $50,000. According to Caddell, Beatty said, “I don’t want your $50,000. People in your position give $100,000!” Whereupon the man promptly wrote out another check for that amount. Says Beatty now, “I didn’t like it, raising the money. u couldn’t help but detect hostility on the part of the candidate for the groveling that he was having to do for that money. You’re dealing not only with quid pro quos that actually exist, you’re also dealing with the appearance of quid pro quos, all of which lower the faith in government on the part of the people. As long as our elections are privately financed, you’re not getting an acceptable level of public service.” Beatty will describe his own campaign contributing only as “sporadic,” adding, “I stopped participating in that charade quite some time ago.”

After Watergate, Beatty came out on top in a California poll ranking potential Senate hopefuls. He was urged to run, but declined. In 1984 he became Gary Hart’s adviser, and again in 1987, when it looked for a moment as if Hart would win the Democratic nomination, before the Donna Rice fiasco blew him out of the water. It is impossible to overestimate Beatty’s disillusionment with what the electoral process had become, turned upside down by the media storm that annihilated both Hart’s candidacy and that of Joe Biden, who was caught plagiarizing a speech.

Initially Beatty welcomed the Clinton victory, but like other liberals he watched in horror as the president gutted welfare and enacted much of the rest of the Republican platform. The 1998 film Bulworth, which Beatty calls “a campaign-finance-reform comedy,” probably the first and last of its kind, marked a watershed in Beatty’s political evolution. It deals with a senator who has sold his soul to special interests and is so consumed with self-loathing that he puts a contract out on his own life, which in turn enables him to speak the truth. Bulworth was by no means the first film with political overtones Beatty had made; Shampoo, Reds, and even the anti-Establishment Bonnie and Clyde all came before. But he had always preferred to work by indirection, and there was nothing elliptical about Bulworth. The picture made it easier for him to step outside the charmed circle of Establishment politics. “Something happened to me, gradually, which made it no longer possible to avoid the truth,” he says. “You can’t really make jokes like that, unless you’re willing to have your invitation to the table rescinded. And I had become more and more willing to have that invitation rescinded. I had become a Bulworth Democrat.”

THE UNCANDIDATE: Beatty is like the mayor of the Beverly Glen Center. Everybody knows him, has a “Hiya, Warren,” a smile, a quick handshake, a hug. Sitting on a terrace outside Starbucks, he reminisces about Rome in the early 1960s, where he worked on The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone. He recalls how many of the young men did nothing all day but sit at cafes on the Via Veneto sipping cappuccinos and staring at the girls. Except that every once in a while Federico Fellini would stop by, or Luchino Visconti, who was a nobleman, and rich, and also a Communist. As Beatty blinks in the blinding beams of sunlight dancing crazily off the parked Benzes,, he says, only semi-ironically, “This is my Via Veneto!”

Suddenly, a tall, stunning blonde, boots up to mid-thigh, appears out of nowhere. She’s clutching two pairs of glasses, one with dark frames, one clear. Looking at Beatty she says, “You be the judge. Which is better?” He goes with the flow, and I figure he knows her, the way he knows everyone else here. She tries on one, then the other. Beatty votes for the clear frames, and she says, happily, “There was a tie—you’re the tiebreaker.” And she evaporates as suddenly as she appeared. He turns to me and says, “Who was that?”

Beatty is at home here; it feels right, and I wonder if he could ever be happy somewhere else, say, Washington, D.C. His well-publicized romances with many of the most talented and attractive actresses on the planet have always seemed like a debit politically, but now the public fatigue with Kenneth Starr’s disclosures has finally put the ghost of Gary Hart to rest. When Arianna Huffington floated the Beatty balloon last August, without his knowledge, the idea was taken seriously by many pundits. Supporters came out of the woodwork to offer their services, including several people prominent in the Gore and Bradley campaigns. The staid Washington Post editorialized, “In 2000 it might just take a Beatty candidacy to slay the money beast.” Even The Wall Street Journal’s conservative op-ed page perked up, printing a surprisingly friendly editorial. Political consultant Roger Stone, a shadowy presence in the Reagan years, approached Beatty to run on the Reform Party ticket. The actor, who is fond of saying “We don’t need a third party, we need a second party,” recalls, “I said, ‘No, I’m a Democrat, I’m not going to do that.’ He said he was then going to go to Donald Trump, and he did.”

Although it’s a cultural cliche to say that the values of the entertainment industry have permeated Washington, this is not strictly accurate; it’s the values of the marketplace that inform both Hollywood and Washington, and no one knows this better than Beatty. “We have this way of counting the grosses on Friday night, and saying, ‘The people want this.’ Well, that’s not necessarily true. If the studio doesn’t get behind the movie and find an exciting way to advertise it and give it a buildup for week after week after week, the picture’s not going to look popular. Well, neither will the agenda of an ideology that is not backed with money and organization and advertising. With the front-loading of primaries, you have the political version of a blockbuster movie. There’s no time for people to discover the movie before it’s kicked out of the theaters.”

Beatty declined entreaties to enter either the New Hampshire or California primary. He felt that, having rejected special-interest money and lacking a professional political organization, which would have taken a year to put together, he was likely to make a poor showing and damage his agenda. As he puts it, people would have said, “‘Look, Mr. Movie Star was up here and tried to do something with these issues and look how unpopular they are.’ Well, I don’t believe that.” Beatty advocates public financing of campaigns, including primaries (and on this he takes a much stronger position than either John McCain or Bill Bradley); Medicare for all; building enforceable sanctions against exploitative labor practices and environmental pillage into the structure of world trade; and addressing the public-school crisis by rebuilding the infrastructure and raising teachers’ salaries.

Reds ends with John Reed’s death, Bonnie and Clyde with Clyde Barrow’s, and Jay Billington Bulworth is apparently killed as well. Life is short, art is long, and the lure of the movies has, after all, defined his life. He says, “You work in a field in which it’s more palatable to express what needs to be expressed in metaphor and in humor and in drama, and then you finally grab the

mike and say, ‘Let’s stop trying to be funny or cute or dramatic, or hide behind metaphors. Let me tell you what I think is wrong.’ It’s exhilarating, but it’s also a fall from grace. It’s much more attractive to me, after the last few months of seeming to endanger so many people’s comfort, to undertake the drudgery of writing, producing, directing, and acting in a movie.”

So what is he working on?

“It’s none of your fucking business.... Can you imagine how much pleasure that gives me to say, ‘It’s none of your fucking business’? If you say to me, ‘What do you mean, single-payer health insurance?,’ I can’t very well say to you, ‘It’s none of your fucking business.’”

Whatever the future holds, first up is Town and Country, a troubled production that has been pushed back. The budget going in was $50 million, and as of December it had spiked to $78 million, with a new ending, yet

to be shot, maybe. Hollywood buzz has pointed the finger at Beatty, the 800-pound gorilla on the set, but New Line production head Mike DeLuca admits that the movie started shooting without a finished script because of scheduling problems: “We just rolled the dice and hoped it would work out.”

Ultimately, it’s hard to say what Beatty’s latest venture into the political fray amounts to. He may have moved Bradley to the left, and if Bradley moved Gore had to move, however fractionally, because he can’t afford to lose the traditional Democratic constituency. But poll-driven Washington consultants are dismissive. Says Mark Mellman, a Democratic strategist, “Beatty is a guy of enormous convictions and a strong moral compass, but the notion there was a strong public demand for a Beatty candidacy is ludicrous.” Beatty himself doesn’t sound like a man who has flitted about the flame and

been singed. “I feel good about speaking up,” he muses. “I wouldn’t feel good if I hadn’t. It seems to me that the effect has been positive, that I’ve not yet made too much of a fool of myself—at least, I don’t think I have. I have not diminished the importance of the issues. One has to be very, very careful not to be an unwitting party to making what most people consider to be unfashionably liberal ideas appear to be more unpopular than they really are. I think the question is: Can I be effective at another time? Whether that is in a year, or two years, who knows?”

Meanwhile, it’s back to the big house on Mulholland Drive, which is too bad in a way. The prospect of Beatty and Bening in the White House is interesting. As Garry Shandling puts it, “Each of them would make a great president. And each of them would make a great First Lady. I aspire to be either one of them.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now