Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

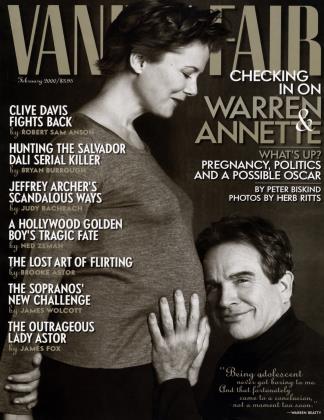

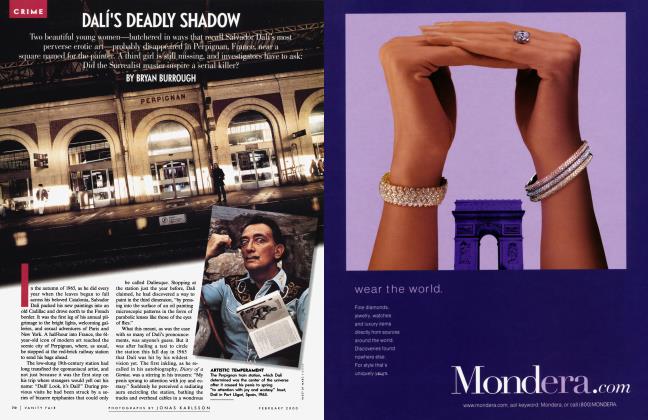

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCelebrated today for the dazzling eloquence with which he inventoried Depression-era America, Walker Evans gave photography a whole new language: the vernacular of the quotidian. A charming rebel in a Brooks Brothers suit, he persuaded the U.S. government and Fortune magazine to fund his explorations, not least the landmark collaboration with James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Anticipating a major Metropolitan Museum of Art retrospective and a PBS film, VICKI GOLDBERG charts how Evans’s portraits of worn-out sharecroppers and abandoned cars, and his use of signs, billboards, and images, shaped a nation’s view of itself

February 2000Celebrated today for the dazzling eloquence with which he inventoried Depression-era America, Walker Evans gave photography a whole new language: the vernacular of the quotidian. A charming rebel in a Brooks Brothers suit, he persuaded the U.S. government and Fortune magazine to fund his explorations, not least the landmark collaboration with James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Anticipating a major Metropolitan Museum of Art retrospective and a PBS film, VICKI GOLDBERG charts how Evans’s portraits of worn-out sharecroppers and abandoned cars, and his use of signs, billboards, and images, shaped a nation’s view of itself

February 2000Richard Benson, dean of the Yale School of Art, says that Walker Evans is the great artist of our time. Benson, who printed negatives for Evans at one point, will hedge a bit if you bring up Picasso, but if you restrict the dialogue to American photography, even American art, it gets harder to disagree with him anyway. Walker Evans rescued entire realms of American life from being undervalued and overlooked. Down-and-out buildings and orphaned architecture, scattershot letters on hand-painted signs, orderly garages and jumbled-up barbershops, empty streets, junkyards, abandoned cars, and worn-out faces had few claims to the status of subject matter before Evans took them on. When no one else was looking, he recognized—maybe even invented—the dignity of anonymous objects and modest achievements.

In the 1930s, Evans coaxed vernacular culture and ordinary existence to center stage, turned representation and images—signs and billboards and photographs—into significant themes in photography, and raised documentary to a new level of complexity. Just as the French Revolution took courtiers out of blue satin knee breeches and clad them in sober black suits, Evans put art photography into workaday clothes.

This brought on one of the quietest revolutions in history, establishing a new field and a new mode of vision. Evans didn’t manage it single-handedly; he just did it better than anyone else. Not many people realized that a revolution was under way until 30 or 40 years later, but if we now know that a tiny wooden church without any grace but God’s is touchingly beautiful, it is because Evans’s photographs proved it to a nation that hadn’t given a damn before.

His work had a powerful influence on Depression-era government photography, on contemporaries such as Ben Shahn (whom he taught to photograph), Helen Levitt, and Harry Callahan, and on major photographers of the 1950s and 1960s, particularly Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander (who says he doesn’t know how any photographer younger than Evans could not be influenced by him), and Garry Winogrand, who said that Evans’s book American Photographs made him realize for the first time that photography could deal with intelligence. Evans has continued to exert an influence on photographers ever since, from Bruce Davidson and Joel Meyerowitz to Robert Rauschenberg and William Eggleston—the street photographers and others who have adopted documentary as the vehicle for American modernist photography.

He is sometimes credited with influencing Pop art too, and he laughingly referred to himself as its inventor, though it may be that the 1960s obsession with commercial culture was just waiting to happen and that artists took Evans’s work as confirmation. Jim Dine and Andy Warhol were both fascinated by Evans; Warhol even titled his photographic homage to Rauschenberg Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, after the landmark book that Evans did with the writer James Agee. Evans had a strong impact on conceptual art as well, even on movies that tried to adopt a documentary look, and he played a primary role in shaping our vision of the Depression. The note he struck has simply become the background music of our environment.

Yet “Walker Evans,” the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s show which opens on February 1 and runs until May 14, is the first comprehensive retrospective to include prints from every period of Evans’s work, including his stint at Fortune and the SX-70 Polaroids he took at the end of his life. Jeff L. Rosenheim, assistant curator in the museum’s Department of Photographs, has assembled 175 prints plus a variety of previously unseen diaries, letters, family albums, magazines, postcards,

and books from the Walker Evans Archive, which was acquired by the Met in 1994. The show will travel to San Francisco and Houston, and on February 10, PBS will air Walker Evans/America, a film by Sedat Pakay. On March 16, another exhibition, “Walker Evans & Company,” will open at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.

Born in 1903, Evans was a rebel in a Brooks Brothers suit. His father was an advertising executive, his mother a social climber. They lived in Kenilworth, a tony suburb of Chicago, and Toledo. Walker meant to be a writer, dropped out of college after his freshman year but read his way through contemporary literature anyway, spent a year beginning in 1926 moping about in Paris, returned to New York, and decided he didn’t write well enough. He had fiddled a bit with photography, but he didn’t take it seriously until 1928 or 1929. By 1930 he was so excited by the possibilities of the medium that he said he sometimes thought himself mad.

Being a photographer was rebellion enough at a time when photography was considered a shabby excuse for a profession. “My poor father decided that all I wanted to do was to be naughty and get hold of girls through photography,” Evans said. “Of course, that made it more interesting for me, the fact that it was perverse.”

If you need to rebel, you can always find a reason. There were those who thought the boom years of the 1920s revealed this nation at its worst. “I was really anti-American at the time,” Evans said. “America was big business and I wanted to escape. It nauseated me. My photography was a semi-conscious reaction against right-thinking and optimism; it was an attack on the Establishment.”

Determined to be an artist, he lived from hand to mouth during much of the Depression; at one point he was so poor he had to sell his books. All his life he yearned to be a millionaire but despised capitalism, and he amused himself when he had a little money by spending more than he had on fancy hotels and waxed-calf Peal shoes. A friend wrote that Evans’s initial interest in him “derived from one particular Savile Row suit—which he so coveted that I promised to leave it to him in my will.”

Primed on modernist European practices, Evans first took photographs strong on design, with odd angles, urban geometries, and montage effects; three in that vein were published in 1930 in Hart Crane’s The Bridge.

But Evans soon tried something different, taking pictures on the street that looked unpremeditated—individuals at rest for a moment in the welter of the city, signs casually scrawled on walls, insignificant subjects he looked at directly, plainly, even brutally, without flourish or embellishment or the traditional tactics of art. He was suddenly in rebellion against the photography of his time, working against what he thought was the dishonest use of the camera by the two reigning masters of the medium, Edward Steichen (too commercial) and Alfred Stieglitz (too arty).

e was more impressed by the succinctness and reality of newspaper photographs and newsreels, postcards (which he collected), reportedly even the pictures in real-estate offices. In his photographic sequence for Carleton —I— —I— Beals’s book The Crime of Cuba in 1933, Evans included a couple of anonymous pictures of atrocities, audacious evidence of his faith in the power of news photographs as well as in the artist’s prerogative to use whatever was at hand. Few American artists back then were inspired by newsreels and news photographs. Evans was.

And the moment was right. It was a documentary era and the camera was its star. Some movie theaters showed nothing but newsreels all day long. Certain sections of John Dos Passos’s book U.S.A. were titled “The Camera Eye,” others “Newsreel.” In Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Agee wrote that “all of consciousness is shifted from the imagined, the revisive, to the effort to perceive simply the cruel radiance of what is. This is why the camera seems to me, next to unassisted and weaponless consciousness, the central instrument of our time.”

In 1931, Lincoln Kirstein, who while still a student at Harvard set up a vanguard magazine and a contemporary-art society that influenced the founding of MoMA, asked Evans to photograph Victorian architecture New England, which most people at the time thought really deserved to be ignored. Evans said, “This undergraduate was teaching me something about what I was doing—it was a typical Kirstein switcheroo, all permeated with tremendous spirit, flash, dash and a kind of seeming high jinks that covered a really penetrating intelligence” about “all esthetic matters.”

Evans loved the Victorian houses, their genteel decay, their quaint rectitude and decorative furbelows, their air of being solid and proper beneath their frippery, as if they were pilgrims wearing lace collars. In 1933, Kirstein arranged for a show of the photographs at MoMA, the first one-man exhibition of photographs in a major American museum.

In 1935, MoMA hired Evans to photograph African sculpture; the writer John Cheever worked as his assistant. That year, while photographing architecture in and around New Orleans, Evans met the painters Paul Ninas and his wife, Jane Smith Ninas (now Jane Sargeant). Paul Ninas had a mistress, who sometimes spent evenings with the couple; when Evans and Jane Ninas fell in love, they made it a brittle foursome. One night, Paul pointed a gun at Walker and told him to take Jane or get out of their lives. Evans got out. He wrote Jane a long, apologetic letter, followed by silence.

He had been hired by Roy Stryker, head of the photographic section of the Resettlement Administration, created in 1935 and later renamed the Farm Security Administration (F.S.A.), a New Deal bureau established to help farmers in trouble. Brought in to win public support for the program, 13 F.S.A. photographers made more than 75,000 prints and 200,000 negatives in eight years—unprecedented proof of the government’s belief in the power of photography.

Evans, who wouldn’t engage in politics, wasn’t about to take government directions, and didn’t believe in social reform through photography, was nonetheless crucial to the F.S.A. Stryker later said that Evans’s pictures greatly expanded his notion of what photographs could do. Evans said that other F.S.A. photographers (including Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee, and Arthur Rothstein) just stole his style and applied it to this propaganda project.

He remained aloof from politics—Jane Sargeant says he didn’t even vote till sometime in the early 1950s and then was nearly hysterical, not knowing how—and he stubbornly resisted authority all his life. While many intellectuals in the 1930s were embracing Communism, Evans did not. “I didn’t want to be told what to do by the Communist Party,” he said, “any more than I wanted to be told what to do by an advertising man for soap.”

Stryker soon discovered that Evans seldom checked in, seldom could be located when out on the road, did not always take the pictures he was asked to take, and, since he primarily used the time-consuming 8-by-10 camera, which gives far greater detail than a 35-mm., wasn’t sending as many pictures to the file as other photographers were. Stryker dismissed him after little more than two years.

Evans was violently opposed to anything that smacked of propaganda, no matter how good the cause. Because he took pictures of sharecroppers, he has been repeatedly misread as a social-reform photographer, a label he couldn’t bear. “I would not politicize my mind or work_The apostles can’t have me. I don’t think an artist is directly able to alleviate the human condition. He’s very interested in revealing it.” Evans was against suborning the camera to charitable causes, against bleeding hearts, special pleading, exploitation, sensationalism, against anything that inserted the artist’s personality, feelings, or political agenda into the photograph.

There were some precedents for this willful removal of the artist from his work. Mathew Brady and other 19th-century Americans took photographs that were plainspoken, straightforward records rather than personal expression, but that was before photography put on the fancy airs of art. In the first quarter of this century, Eugene Atget had mined a vein of poetry in the unassuming doorways and shop fronts of Paris. Evans knew the work of both men but said his primary influences were Charles Baudelaire and Gustave Flaubert, who wanted the author to disappear in the work. Evans had also read modernist doctrines of impersonality by-writers such as T. S. Eliot, who said, “Poetry is not a turning loose of emotion, but an escape from emotion; it is not the expression of personality, but an escape from personality.” Evans set out to meld art with the flat, impersonal rhetoric of documentary photography and produce images that would be, as he put it, “literate, authoritative, and transcendent.”

And deceptively plain. When the photographer John Szarkowski, who was director of MoMA’s photography department from 1962 to 1991, first saw Evans’s book American Photographs as a sophomore in college in the 1940s, he was so baffled that for a minute he thought it might be a practical joke. Where, in God’s name, was the art? It was mostly just facts, he said, and any self-respecting sophomore could tell you that just-facts were not art. Szarkowski changed his mind. MoMA’s 1971 retrospective put Evans on the map in a big way.

In 1935 and 1936, working mostly for the F.S.A., Evans, in a virtual blaze of creativity, produced one picture after another that was tersely and dazzlingly eloquent about America and its history, and sometimes about the history of time itself. It was as though everywhere he looked the world spoke to him of something profound. In Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, he photographed a graveyard in the foreground, workers’ houses in the middle ground, and factories behind, his lens compressing the distances so that the three zones jam up against each other as if they were indivisible. Here are whole lives—birth, work, death—in thrall to the factories and their owners. A woman came to the F.S.A. and requested a print. Asked why she wanted it, she replied, “I want to give it to my brother, who’s a steel executive. I want to write on it: Your cemeteries, your streets, your buildings, your steel mills. But our souls. God damn you.”

He photographed the signs on a building in South Carolina that was a veritable entrepreneurial index, with notices for an art school, a public stenographer, a fish company, and fruits and vegetables, all in different typefaces, like a smorgasbord of alphabets, topped off with a sign saying, GENERAL LAFAYETTE SPOKE FROM THIS PORCH 1824—the past and present life of a southern town spelled out in commerce and placards. Evans was one of the first to realize that the decade’s history was being written by advertising of one sort or another, with signs spreading over buildings like kudzu.

He commemorated the endless grid of portraits in the window of a Penny Picture Studio, where ordinary citizens had exercised their right to be represented. In effect they posed again for Evans, who re-presented them, making the studio photographer’s art his own, years before that idea occurred to the general run of artists. The picture is a riff on photography and time as well: the camera preserved these people in memory, and Evans preserves them doubly, yet only in representation after all. The babies and teens and men in suspenders in that window are different by now, or gone. Photographs are merely stopgaps with smiles.

With Puritan austerity, Shaker simplicity, and Protestant thrift, as well as a certain affection and occasional wit, Evans limned the implications in scenes and faces and postures. Here were the things of this world, things as they were, secretly broadcasting their histories of being built, lived in, discarded, of having had experiences that just might shine through the documented surface if you peered closely enough. A storefront is just a storefront, a street just a street, and yet they are not: they are the sites and evidence of human life and social history, influenced by tradition and commerce and necessity, inhabited by memory and expectation.

In the summer of 1936, Evans got leave from the F.S.A. to go south with Agee for a Fortune article on sharecroppers. Evans was emotionally aloof, in person as well as in his photographs; Agee leaked guilt and confession from his pores. Agee conversed in a steady torrent, unstoppably, like Niagara, and in later years, when Evans sometimes staggered away from his monologues in the wee hours, exhausted, that inveterate talker would follow him into the bedroom to pursue his stream of thought. Evans once said, “I’m embarrassed by the subjective, I’m embarrassed by Agee’s prose, great as I think it is. I could never imagine myself in a confessional mood or an exhibitionistic one.”

The two of them spent several weeks with three sharecropper families. Evans took portraits, mostly letting his subjects pose themselves. One woman gives a shy, graceful fillip to a sack dress that betrays her utter poverty; another stares hard at the lens without a hint of either vanity or self-pity. A family assembles in a bedroom—bare feet, scratched shins, dirty clothes. The boy, half naked, laughs; the rest are self-contained, even solemn, perhaps evaluating the photographer, all possessed of an obscure dignity as surely as any merchant family in a daguerreotype.

Evans’s refusal to politicize, proselytize, or propagandize equalized the differences between a photographer with a salary and subjects without, between the looker and the looked-at. He insisted that human beings in any circumstances whatever were valuable enough in themselves not to be objects to him or to anyone else, and that they be taken on their own terms, not on terms of charity or prejudice or knee-jerk reactions to class.

Some say he exploited these families and made them look worse than they were, but William Christenberry, a sculptor and photographer who first saw the photographs in the 1960s and recognized a family that had lived near his grandparents, says he showed the book to one of the children in the photographs, who said, “We loved Mr. Jimmy and Mr. Walker. They would send us Christmas gifts.”

Evans photographed the sharecroppers’ simple, hand-built houses and their raggedy interiors, framing the rooms so exquisitely and lighting them so carefully that they tend to look like Vermeer on a stringent diet. He photographed southern towns too, the isolated stores and minstrel-show posters, the men on benches waiting long hours for nothing. These deadpan reports of buildings and streets and weary faces are history texts, cultural accounts, critiques of America, somber assessments of the human condition. Evans was highly aware of the camera’s indissoluble marriage to history; he wrote that he was “interested in what any present time will look like as the past.”

Agee’s text was so long and so late that Fortune would not publish it. In 1941, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men came out in book form, with Evans’s photographs, as he had insisted, grouped before the title page without captions, wordlessly divulging secrets about the degree of order that can be wrested from the disordered existence of too little money and too much hard work. The critic Lionel Trilling called the book “the most realistic and important moral effort of our American generation,” but with Europe at war and the Depression beginning to lift, no one was interested, and Let Us Now Praise Famous Men sold just over 600 copies.

In 1938, MoMA mounted “Walker Evans: American Photographs,” a 100-photograph retrospective accompanied by a catalogue. Evans grouped the photographs in the book in two sequences, without captions. The opening series—which includes pictures of photographs and other kinds of portraits (including the Penny Picture Studio)—comments not just on the record before our eyes but also on the spread of images across the world. Then there are automobiles, an auto graveyard with dead cars in a skeletal traffic jam, street people and lonely streets, Depression casualties, a coal miner’s house with boisterous ads on the walls proclaiming the good life, all set out in the quietest photography in the world, not a footfall or a whisper, only the inaudible sigh of time as it seeps away.

The second section opens on a relic, a smashed piece of tin stamped with classical designs. The photographs advance through towns built around factories and railroads, a few fields and some industry swallowing them, then bare-board churches and houses that as the pages are turned grow more elaborately decorated, until the book ends with another tin relic, another bit of ersatz grandeur fallen on hard times—American culture, created by unsung builders and craftsmen trying to make the prosaic present beautiful before time unravels it. Evans once said, “I am fascinated by man’s work and the civilization that he’s built. In fact, I think that’s the interesting thing in the world, what man makes.”

Sequence was of the utmost importance to him. His photographs change meaning as they echo and interact with other pictures. Near the end of the first section, a poster for a Carole Lombard movie in front of a couple of ungainly houses suggests the illusory lures of Hollywood dreams, but when you turn the page and the one after that, the dreamers are out-of-work men with no place to sleep but the street, and the last picture in the section is of a ruined plantation house blocked by an enormous, uprooted tree—a way of life built on an untenable dream that came at last to nothing.

The author who disappears in his work expects us to spend time making our own connections and conclusions as a photograph on one page comments on one before. Evans asks a lot of his audience. If instant gratification is the goal, he seems to say, there are always the picture magazines, like Life (which he hated), but the kingdom of poetry was not built in a day.

William Carlos Williams wrote about American Photographs that “it is ourselves we see, ourselves lifted from a parochial setting. We see what we have not heretofore realized, ourselves made worthy in our anonymity.” Others thought the book jaundiced, complaining that it was unfairly critical of this country at a time when it needed boosting. Ansel Adams wrote Edward Weston about it: “I am so goddam mad over what people from the left tier think America is.”

T n New Orleans, Paul Ninas showed his -Lwife the dedication page with her initials, J.S.N. She was astonished. It was the first sign she had had from Evans since his good-bye letter three years earlier. He began a clandestine correspondence, with missives no bigger than Chinese fortunes tucked into letters from one of her friends. She found an excuse to go east, refused to return to a marriage already in tatters, and in 1939 moved in with Evans. They were broke. After the MoMA show, Evans was indisputably a master, at least to the few who cared about photography then, but he could not get work. Sometimes Agee gave them $10 to get through the week. Walker and Jane married on the spur of the moment in 1941.

A complex man and one prone to depression from early in life, Evans was equipped with a klieg-light charm that is said to have illuminated rooms when he came in the door. James Stern, a colleague at Time during World War II, said, “There was Walker the intellectual, Walker the pedagogue, the hypochondriac, the man-abouttown, the boulevardier—I was about to say lover. There were women, I know, who loved and admired him but considered him ‘wicked,’ a bit of a scoundrel.” Bill Stott, professor of American studies and English at the University of Texas, who knew Evans late in life, says his talk was “generally brilliant and gaudy and full of aphorisms.”

There was also the devilishly clever Evans. The artist Mary Frank says that one year, when he had not gotten an expected invitation to Cape Cod, she received a letter from him that read roughly like this: “Dear Walker, It’s so wonderful up here, the only thing wrong is I’ve been missing you really a lot.... Please let me know when you could come.” Once when Richard Benson finished printing an Evans portfolio, someone asked Evans to sign three empty picture mounts in case one should get damaged and need to be replaced. An artist’s signature is valuable, but Evans graciously consented; he signed one Abraham Lincoln, one Walt Whitman, and one Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In 1938 he had a new project, to photograph unsuspecting subjects in the subway. He hung his Contax about his neck like a tourist but neither touched it nor put it to his eye, so no one realized he was photographing by means of a long cable strung through his sleeve to a shutter release in his hand. He went underground to catch strangers unawares, with their guards down and their faces naked. The light was dim, the train lurched, his camera position was effectively fixed, and he depended on luck to put good subjects on the bench opposite his seat. He had purposely given up a large measure of control to photograph people who had unwittingly given up control over their own images; no one would tell them to smile for the birdie. Evans had introduced chance into the photographic domain, where portraiture did not take chances.

The pictures were not published for a long while, but in 1966 MoMA exhibited them, and a book called Many Are Called brought them a wider audience. Evans knew perfectly well how intrusive these pictures were; he once

referred to himself as a “penitent spy and apologetic voyeur.” The photographs were one of the higher-class signposts on the road to the general breakdown of privacy. Evans regarded them as a kind of inventory of “the people,” that core identity the 1930s was so eager to find: “As it happens,” he wrote, “you don’t see among them the face of a judge or a senator or a bank president. What you do see is at once sobering, startling, and obvious: these are the ladies and gentlemen of the jury.”

From 1943 to 1945, Evans reviewed movies and sometimes art and books for Time magazine. Gas and film were scarce during the war years, making photography difficult, and he had a full-time job, but he was always short on energy anyway and didn’t seem charged up with ideas that would push him out the door with his camera. It must have added to his depression that no one was commissioning him to go out, either, and possibly he knew he had already reached his peak. At least he was writing, as he’d always longed to do. He had a taste for popular movies rather like his taste for vernacular architecture. Reviewing Coney Island, he wrote, “The Technicolor cameras of this picture will turn many a spectator green with envy. They have been allowed a prolonged fondling of Betty Grable.”

In 1945 he joined Fortune as the only staff photographer and later became the magazine’s special photographic editor. He was always ambivalent about being an artist in a capitalist lair, but he managed to maintain his independence and do pretty much what he wanted—which wasn’t very much— for 20 years. He met with a higherup now and again and passed some ideas by him, then took off with his camera and didn’t come back for a couple of months. Evans must have been a master of manipulation, having managed to persuade first a government bureau and then the Luce empire to pay him a living wage to do what he wanted in his own sweet time. Over two decades he published some 40 portfolios and photo essays in Fortune, including a couple of essays culled from his postcard collection.

He was still exploring, if not so often discovering. He pursued the issues of selfremoval and lack of control by assuming a fixed vantage point on the street and photographing passersby. He recorded the passing scene through the window of a moving train. He claimed that color photography was vulgar, but he published several color essays. And he kept on looking for American life and traditions in the way that life was lived and constructed, on the streets of Chicago, in old New England hotels, old train depots, old office furniture.

He spent less and less time with Jane and so much of his social life without her that some of his friends and colleagues didn’t know he was married. All his life Evans had been certain he was an artist, and when he quarreled with her would say, “I don’t think you know who I am!” When she got a gallery show at last and a tiny taste of success, he thought she was competing with him, and painting became so difficult she almost stopped. She left him in 1955 to marry another man.

In 1959, Evans met Isabelle Boeschenstein von Steiger (now Storey), a Swiss designer, exceedingly pretty, worldly, and almost 30 years younger than he. A year and a half later she divorced her husband to marry Evans. His friends included literary types such as Lionel and Diana Trilling and Mary McCarthy and Edmund Wilson, as well as a bohemian crowd of artists including Mary and Robert Frank, but Evans always kept his acquaintance circles entirely separate. Isabelle Storey says that when she met him he had recently become very social,

spending a lot of time with people such as Jock Whitney. Evans the artist and rebel was a not-so-closeted aristocrat at heart. “He was an artist with a dinner jacket,” Storey says. “We were invited everywhere.”

He was invited to Yale too, to give a lecture in 1964, and then to teach. He used some students shamelessly to help him out and lend him money, but they thought him a great man whom they were privileged to assist, and he was exceptionally generous to them too. He quit Fortune, where he had become a luxury. He and Isabelle built a house in Lyme, Connecticut, but the marriage was already in trouble. Evans had begun to drink heavily, and when his wife taught for a semester in Switzerland, he accused her of deserting him. As attractive as he was to women, and as endlessly fascinated as he was by them, he remained an Edwardian who could not imagine that a woman was equal to him in any way. Isabelle Storey left him in 1971.

In 1973, just two years before he died, Evans bought a Polaroid SX70 camera. He was frail, but the camera was so easy to use that he became excited anew by photography. He worked at high intensity, in color, making more than 2,400 pictures in eight months: close-up portraits, everyday architecture, interiors, signs. Little of this work has been seen until now.

He became an obsessive collector, passionately gathering trash, ticket stubs and shells, sometimes making collages with them, filling the back of his house so completely that half his bed was covered and he’d have to push things aside to slip his thin body between the sheets. Once, he bought the entire contents of a yard sale, borrowed a truck, and dumped them on a friend’s lawn. He collected old signs too, inveigling young friends to help him steal them. On one such occasion, William Christenberry, stunned to realize what he had just pulled off, asked Evans what they would have done if the police had stopped them. “Aw, hell,” said Evans, “we’d have told them it was a fraternity prank.” He was nearly 70 years old.

In his photographs he already owned the vernacular, the hand-painted signs, the ads, the crushed relics, the marginal crafts of American life. Late in life he simply brought them home. He had already lifted the artifacts into public consciousness and hinted that if you put them together in the right order they would sing a national anthem in a new key. And they did, and it had a mournful sound, and it kept time to the beat of American history. It plays throughout the land even today.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now