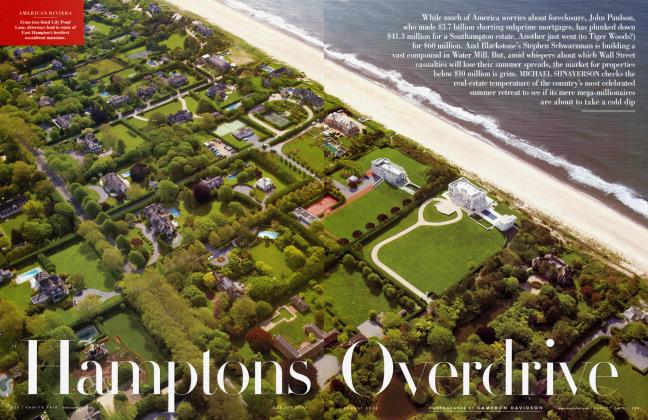

Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

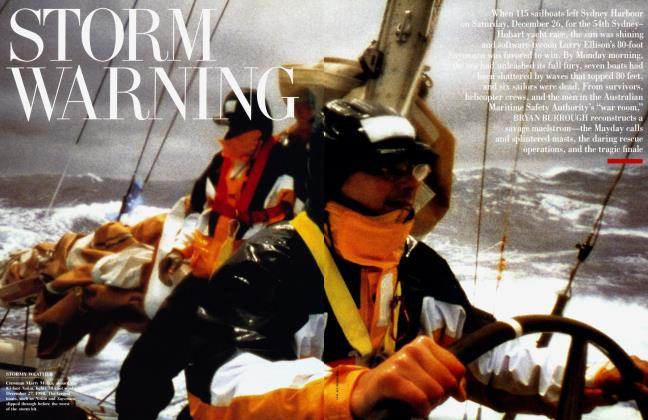

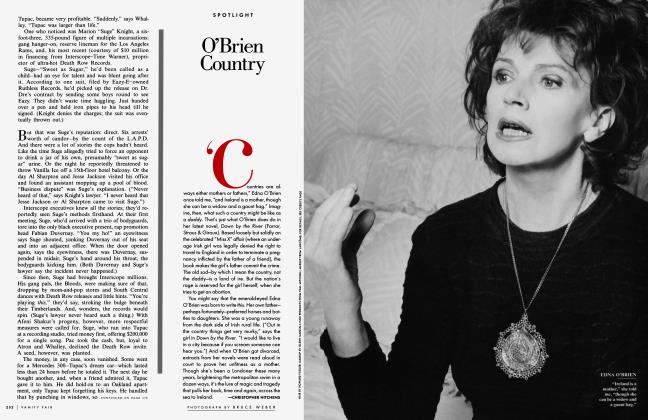

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWith her prodigious talent—manifest in 13 books and almost every literary prize except the Nobel— Eudora Welty could have reigned as the grande dame of American letters. But her sense of the ridiculous, her thirst for experience, and her deep attachment to her childhood home in Jackson, Mississippi, have made her something much more precious. For Welty's 90th birthday, her friend of many years WILLIE MORRIS pays tribute to the woman whom many consider the United States' greatest living writer

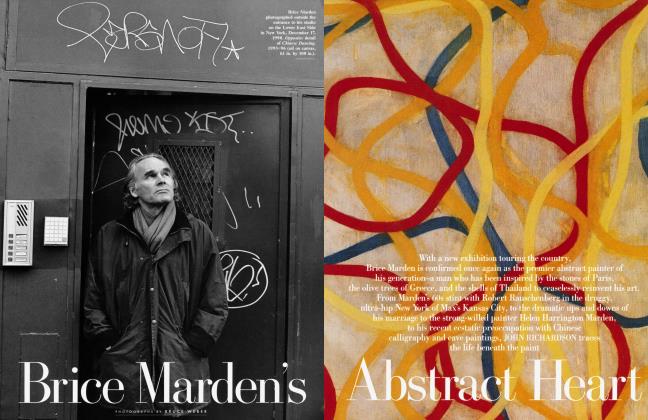

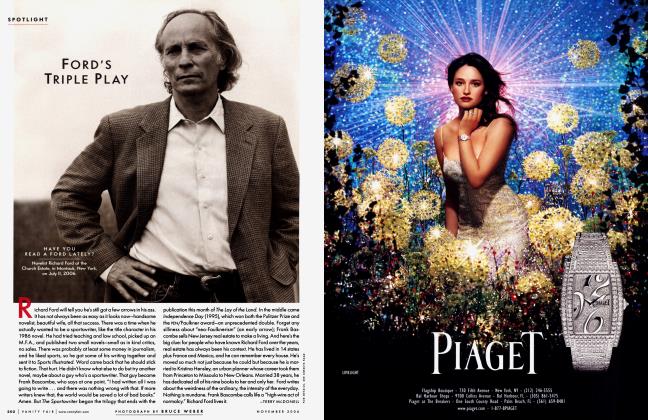

May 1999 Willie Morris Bruce WeberWith her prodigious talent—manifest in 13 books and almost every literary prize except the Nobel— Eudora Welty could have reigned as the grande dame of American letters. But her sense of the ridiculous, her thirst for experience, and her deep attachment to her childhood home in Jackson, Mississippi, have made her something much more precious. For Welty's 90th birthday, her friend of many years WILLIE MORRIS pays tribute to the woman whom many consider the United States' greatest living writer

May 1999 Willie Morris Bruce WeberThe night sky over my childhood Jackson was velvety black. I could see the full constellations in it and call their names; when I could read, I knew their myths. Though I was always waked for eclipses, and indeed carried to the window as an infant in arms and shown Halley's Comet in my sleep, and though I'd been taught at our dining room table about the solar system and knew the earth revolved around the sun, and our moon around us, I never found out the moon didn't come up in the west until I was a writer and Herschel Brickell, the literary critic, told me after I misplaced it in a story. He said valuable words to me about my new profession: "Always be sure you get your moon in the right part of the sky."

—Eudora Welty, One Writer's Beginnings.

One recent Sunday I drove Eudora Welty along the spooky, kudzu-enveloped dirt and gravel back roads of Yazoo County, Mississippi, some 40 miles north of Jackson. Dwarfed like a child by the stark bluffs outside the car window, she rode shotgun through the sunlight and misty shadows. "I haven't even seen another car yet," she noted at one point. "When was the last time we saw a human being?" Her voice, according to her friend the novelist Reynolds Price, remains "shy, but reliable as any iron beam."

She was game for anything, always peering around the next bend. At the crest of a bosky hill, a narrower and darker byway intersected with the one on which we were traveling. "Eudora, I'm going to make a left and drive down Paradise Road," I said. "We'd be fools if we didn't," she replied.

One of Eudora Welty's fictional characters had occasion to remark that against old mortality life "is nothing but the continuity of its love." Welty, often called the Jane Austen of American letters, has charted this continuity in 13 books, including: three novels (The Optimist's Daughter, published in 1972, won the Pulitzer Prize); five collections of short stories; two novellas; a volume of essays; an acclaimed memoir, One Writer's Beginnings; and a children's book. (She has also published two volumes of her photographs, taken in Mississippi and elsewhere.)

Her work, marked by what the critic Jonathan Yardley calls an "abiding tolerance ... a refusal to pass judgment on the actors in the human comedy," has won every literary prize except the Nobel, for which she has frequently been mentioned. Says Price, "In all of American fiction, she stands for me with only her peers—Melville, James, Hemingway, and Faulkner— and among them she is, in some crucial respects, the most life-giving." She once wrote, "My wish, indeed my continuing passion, would be not to point the finger in judgment, but to part a curtain, that invisible shadow that falls between people; the veil of indifference to each other's presence, each other's wonder, each other's human plight."

Eudora Welty, whom many consider America's greatest living writer, was born in Jackson 90 years ago. On April 13 she enters her 91st year. She is abidingly revered in her hometown, where her birthdays are cause for celebration. In 1994, when Eudora and friends gathered at her favorite restaurant, Bill's Tavern (which she helped get started by supplying quotes of praise for the newspaper), a Greek belly dancer performed. Above her navel were written the words "Eudora Welty I love you." During another celebration, at Lemuria Bookstore, letters were read from comrades and admirers around the world, including President Clinton. John Ferrone, her Harcourt Brace editor, wrote:

Hail Eudora

Staunch perennial

I'm looking forward

to your centennial

Eudora, who is quite simply the funniest person I have ever known, could easily have become the grande dame of American letters, but clearly would have found herself tittering at such a self-important posture. She is wryly self-effacing with a gentle irony. Our connections go back considerably, for I was born in a house two blocks from hers in the Belhaven neighborhood of Jackson and christened in the church of her childhood, Galloway Memorial Methodist, where as a girl she took nickels to Sunday school in her glove. I met her when I was eight or nine and can pinpoint exactly where: Eudora always shopped for groceries at an erstwhile establishment called the Jitney Jungle, which had wooden floors and flypaper dangling from the ceiling. One afternoon during World War II, on one of my many sojourns into Jackson from my home in Yazoo City, I accompanied my great-aunt Maggie, who was wearing a flowing black dress, to fetch a head of lettuce, or a muskmelon perhaps. Eudora was at the vegetable counter when my great-aunt introduced us. I remember her as tall and slender, her eyes luminous blue. As we were leaving, my great-aunt whispered, "She writes those stories her own self. "

Through the years I have learned to expect certain kinds of reactions from Eudora. For example, when one telephones her for a meeting, she does not say, "Let's have lunch," but rather, "We must meet." Her conversation is laced with phrases such as "That smote me," and with solicitous interrogations, including "Don't you think?" or "Can't you imagine?" Josephine Haxton of Jackson, who writes under the nom de plume Ellen Douglas, first met her many years ago when Eudora went to Greenville, Mississippi, to sign copies of a book called Music from Spain. "Many years later, when my children were long since grown and had children of their own," Josephine tells me, "Eudora said to me, 'Oh, I remember so well that day I came to Greenville to sign books. Your children—those beautiful children.'" Others recall such instances of her magnanimous spirit. One of them, the historian and novelist Shelby Foote, tells me, "In Eudora's case, familiarity breeds affection."

Stories about her have always abounded in Jackson. In the 1930s there was not much to do in town and she and her comrades had to look hard for entertainment. They were especially intrigued when one Jackson lady announced in the paper that her night-blooming cereus was about to blossom. According to Eudora's friend Suzanne Marrs, "Eudora and her group would often gather to attend the bloomings, and they eventually formed the Night-Blooming Cereus Club, of which Eudora was elected president. Their motto was: 'Don't take it cereus; life's too mysterious.'"

Patti Carr Black, recently retired as director of the Mississippi State Historical Museum, is one of the best sources of Welty anecdotes. "My favorite hours," she says, "are spent with Eudora in the late afternoon sipping Powers Irish Whiskey and going back in her incredible memory to high times in our favorite spot, New York City. She quotes entire Bea Lillie lyrics, especially 'It's Better with Your Shoes OfF; delivers Bert Lahr punch lines; and describes the moves of the Marx Brothers and W. C. Fields, including Fields's wiggle of his little finger. She also does a great rendition of Mae West inspecting the troops up and down."

But it isn't just the locals who savor their memories of Eudora. William Maxwell, who was her editor at The New Yorker beginning in 1951, loves to recall her visits to New York, particularly one specific night. "When I first got to know her she was staying in the apartment of her friend and editor at Harper's Bazaar Mary Louise Aswell, and what I remember of the evening is Eudora's acting out of her mother telling her niece the story of Little Red Riding Hood while simultaneously reading Time magazine. It could have been transferred to the stage without a single change of any kind, and I didn't know anybody could be so hilarious. Some years later, when we were living on the fifth floor of a walk-up in Murray Hill, she came with the manuscript of a novella, The Ponder Heart, and after coffee we settled down to hear her read it. In no time I was wiping my eyes. Nothing has ever seemed so funny since. What the world must be like for a person with so exquisite a sense of humor, I don't dare think."

At dinners these days Eudora's stories move here and there like a gentle breeze that emanates from Greenwich Village in the Prohibition years, past the names of friends long dead, and on to her travels through Mississippi with her Kodak during the Depression, when she worked as a photographer. Questions provoke peregrinations. "Eudora," I asked during a recent gathering, "would you like a little kitten? I have one named Bubba." "Well," Eudora began, "mine has been a dog house all my life. My mother can't stand the thought of a cat. Of course, she's been dead a number of years. I like little kittens, but I don't think I can take one. I remember [novelist] Caroline Gordon. The first time I ever saw her, I was living in the Village, and I was going to meet her. I was walking along Eighth Avenue and she was carrying around a bunch of newborn kittens with her, and she'd go up to people on the street and say, 'You look like a cat person. Wouldn't you like a kitten?' It didn't work very well. She had a good many left. Whatever became of those kittens, I've wondered."

No one else answers questions in quite this way now, not even in Jackson.

Eudora has never married, and she lives alone in the house her father built in 1925 when she was 16 and the nearby streets were gravel and there were whispery pine forests all around. On the front lawn is a oak tree. ("Never cut an oak," her mother advised her.) The kitchen of the old house looks out on a deep-green garden with its formal bench beneath another towering oak tree. Eudora loves what she still calls "my mother's garden" and says she was "my mother's yard boy."

"My wish would be not to point the finger in judgment," Welty has said, "but to part a curtain—that invisible shadow that falls between people."

Her Tudor-style house has a sturdy vestibule, a brown gabled roof on the second story, and a screened-in side porch long unused. Excluding the time she has spent traveling, she has lived and worked here for 74 years. "I like being in the house where nobody else has ever lived but my own family," she says, "even though it's lonely being the only person left."

She calls it "my unruly home." Books of all kinds are everywhere, stacked in corners, on tables and chairs. There are mountains of books, and on every flat surface one finds unanswered mail. Her correspondence is so voluminous, she says, that she is unable to handle it. In a box on a table is the Richard Wright Medal for Literary Excellence she received in 1994. "I'm proud to have it," she says.

These days Eudora does not dress up for visitors. On the morning of one of my calls she was wearing a blue sweat suit and white sneakers. Her short hair curls around the top of her ears. Her eyes are large, very blue, a little sad, yet still, at times, vibrant with mischief. She sits near a front window in an electric lift chair that makes it easy for her to stand up. She calls it her "ejection seat." If it is late afternoon and she feels up to it, she will press the button to raise herself to an upright position and suggest you join her in the pantry while she pours a couple of Maker's Marks. "This is what Katherine Anne Porter called 'swish likka,"' she says, quoting "swich licour" from Chaucer. "This is powerful stuff." Then, faithfully at six P.M., she turns on the television for her favorite program, The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer.

Every conversation is a procession of supple images. One day after a winter storm in Jackson—the first real one here in years—she recalled for her friend Hunter Cole the first time she saw snow, from her elementary-school windows on North Congress Street. It was not cold enough for it to stick, she recalled, so the teacher raised a window, took off her cape, and extended it outside. Then the woman walked hurriedly about the classroom with the garment, showing the young writer and her contemporaries the glistening snowflakes.

She is not, by birth, what is called here "Old Jackson." Her father, a northerner originally from Ohio, was the top man in a fledgling insurance company. Her southern mother had been born in West Virginia. "I was always aware," Eudora has written, "that there were two sides to most questions." Before they built the house in Belhaven the Weltys lived on North Congress Street, right down from her elementary school. (The writer Richard Ford later grew up directly across from the old Welty house.) The family was by no means rich but lived comfortably, and Eudora's parents were particularly attentive to her. In One Writer's Beginnings, Eudora wrote of mornings in the household of her childhood. "When I was young enough to still spend a long time buttoning my shoes in the morning," she began, "I'd listen toward the hall: Daddy upstairs was shaving in the bathroom and Mother downstairs was frying the bacon. They would begin whistling back and forth to each other up and down the stairwell. My father would whistle his phrase, my mother would try to whistle, then hum hers back. It was their duet. I drew my buttonhook in and out and listened to it—I knew it was 'The Merry Widow.' The difference was, their song almost floated with laughter: how different from the record, which growled from the beginning, as if the Victrola were only slowly being wound up."

Her father, Christian Webb Welty, had "an almost childlike love of the ingenious." Eudora believes he owned the first Dictaphone in town and he put the earphones over her ears to let her discover what she could hear. He also owned one of the early automobiles, in which the family made long journeys on perilous gravel roads to Ohio and West Virginia. Her father told Eudora and her two younger brothers, Walter and Edward, that if they were ever lost in a strange land to look for where the sky is brightest along the horizon. "That reflects the nearest river. Strike out for a river and you will find habitation." This helped provide her with what she terms "a strong meteorological sensibility." As for her mother, Chestina Welty, "valiance was in her very fibre."

The Weltys loved literature. They had an encyclopedia in the dining room, and if someone had a question at the table, someone else was always jumping up to prove the other right or wrong. As a girl, Eudora's mother had been given a complete set of Charles Dickens's novels as a reward for having her hair cut, and when the Welty home caught fire one night before Eudora was born, Mrs. Welty—on crutches at the time—returned to the house and threw all 24 volumes one by one out the window for Mr. Welty to catch.

It was a disappointment to the young Eudora to discover that storybooks had been written by people, "that books were not natural wonders, coming up of themselves like grass." She was in love with books, their words, their smell, their covers and bindings. The public library was on the other side of the state capitol from her home, and on her trips to get books she would glide along the marble floors of the capitol on roller skates. This produced "very desirable echoes."

At the library itself, Mrs. Calloway, a witchlike lady with a dragon eye, intimidated the children. But she could not inhibit Eudora's reading, for her mother had told the librarian: "Eudora is nine years old and has my permission to read any book she wants from the shelves, children or adult, with the exception of Elsie Dinsmore."

She was absorbed by the stories all around her, the eternal and ubiquitous Mississippi storytelling she heard from family, neighbors, maids. Preparing for a Sunday-afternoon ride, she would settle onto the backseat between her mother and a friend and command, "Now talk!"

At the time, Jackson girls took piano lessons as a matter of course. Eudora's own teacher, "Old Jackson" to the core, dipped her pen in ink and wrote "Practice!" on her sheet music with a P that resembled a cat's face with a long tail, and slapped her fingers with a flyswatter when she made a mistake.

Even as a child she was drawn to the bizarre, the grotesque, the phantasmagoric. "This being the state capital, we had all the state institutions in Jackson—blind, deaf and dumb, insane," she once observed to me. "Made for good characters." There was also the occasional society murder, which Eudora found singularly fascinating. She recalls the Mississippi matron whom I myself had heard about who was convicted for the murder of her mother; part of the corpse was found, but not all of it. She was sent to Whitfield, the asylum. Eudora and all of us heard the stories of the bridge games the murderess played with other proper ladies confined there for alcoholism. One afternoon one of the ladies abruptly tossed down her bridge hand and said, "Not another card will I play until you tell me what you did with the rest of your mother."

In Eudora's childhood years, the two Jackson newspapers published the honor rolls and individual grades of all the honor students. Also, the city fathers gave the honor children free season tickets to the baseball games of the noble Jackson Senators of the Class B Cotton States League. Eudora adored Red McDermott, the Senators' third-baseman, and offered him her documents attesting to her 100s in all her subjects, even attendance and deportment. At age 12 she won the Jackie Mackie Jingle contest, sponsored by the Mackie Pine Oil Company of Covington, Louisiana; the company president sent her a $25 check and said he hoped she would "improve American poetry to such an extent as to win fame."

Eudora spent two years in the little town Columbus, Mississippi—Tennessee Williams's birthplace—at the Mississippi State College for Women. Although "the W," as it is called, was impoverished, neglected, and overcrowded, Eudora remembers it as a place of great intellectual stimulation, with a dedicated cadre of female teachers who taught without pay for months during the Depression when the state could not pay their salaries. The college brought together 1,200 girls from every corner of Mississippi. They all wore identical uniforms, but Eudora learned to tell where a girl had grown up from the way she talked, ate, or entered a classroom. She once told me that she could distinguish a girl from the Delta by the way she walked.

Eudora became a cartoonist for the school paper and was chosen fire chief of Hastings Hall. At night she frequently sneaked out of the dorm to go downtown, where the action was, and, on one such evening, won a Charleston contest at the Princess Theater. Elizabeth Spencer first met Eudora some years after this when the former was a college student. "I was in great awe of her talent," Elizabeth remembers, "but I was not aware of her high-flying sense of humor." Then one afternoon the two of them were at a post office and noticed a tacked-up poster proclaiming: NO LOITERING OR SOLICITING. "Eudora saw it," Elizabeth recalls, "and said, 'Let's loiter and solicit.'" When Elizabeth said O.K., Eudora declared, "Then you solicit while I loiter."

Eudora's father, the northerner, wanted his daughter to spend her last two college years at some distinguished university up North, and in 1927 she enrolled at the University of Wisconsin. Her mother was already encouraging her aspirations to become a writer, and Mr. Welty gave his daughter her first typewriter, a little red Royal Portable, which she took with her to Madison. To get her through the harsh winters he also bought her a possum coat at Marshall Field in Chicago. Many of the students, she recalls, had raccoon coats, but her family could not afford such luxury.

At first, the Midwest frightened her. Years later she wrote her longtime agent, Diarmuid Russell, about her first months above the Mason-Dixon line: "I was very timid and shy, younger than the rest and those people up there seemed to me like sticks of flint that live in the icy world. I am afraid of flintiness—I had to penetrate that I used to be in a kind of wandering daze, I would wander down to Chicago and through the stores, I could feel such a heavy heart inside me. It was more than the pangs of growing up, much more. It was some kind of desire to be shown that the human spirit was not like that shivery winter in Wisconsin, that the opposite to all this existed in full."

Her father, concerned about his daughter's future, persuaded her to go to graduate school in business. She immediately chose Columbia University because she wanted to live in New York for a year. She studied typing for a while, "so I could be a secretary and make a living." When she had to pick a major subject she selected advertising, "which wasn't awfully good, because all at once, when the Depression hit, nobody had any money to advertise with. For that matter, nobody had any money to do anything with." During the Manhattan winter her mother sent her boxes of camellias to remind her of home.

In 1931, shortly after Eudora returned to Jackson from New York City, her father died of leukemia. Her mother was left with two sons in high school and college, so Eudora worked at whatever she could do. Her first job, at age 22, was at a local radio station headquartered in the clock tower of Jackson's first skyscraper: the Lamar Life building, which had been built by her father's company.

As part of her job she wrote the radio schedule to mail out to listeners and also sent fake letters to the station which were to be read on the air: "Dear WJDX, I love the opera on Saturday. Don't ever take it away!" She remembered the office as being "as big as a chicken coop," with just enough room for Mr. Wiley Harris, the announcer and manager, and herself. He would go up into the clock tower to clean out the canary's cage, and she would yell "Mr. Harris! Mr. Harris!" because it was time for him to announce the call letters of the station. The absentminded Mr. Harris would come down and say, "This is Station ... uh, this ... This is Station ..." Eudora would write the call letters—WJDX—on a sheet of cardboard and hold it up for him.

Later, still during the Depression, she was hired as a publicity agent, junior grade, with the Works Progress Administration. She visited the farm-to-market roads in Mississippi and interviewed people living along them. She rode around on bookmobile routes and helped put up booths at county fairs. She visited landing fields being hacked out of cow pastures, juvenile courts, the scene of the devastating Tupelo tornado, and even a project teaching Braille to the blind. She went mostly by bus and stayed in the old small-town hotels. At night, under a squeaky electric fan, she wrote up the projects for the county weeklies. The Depression, she would remember, "was not a noticeable phenomenon in the poorest state in the Union."

For her own gratification, she began taking photographs, using an old-fashioned Kodak. The Standard Photo Company of Jackson developed her film, and she printed it at night in her kitchen at home. She says that her years of "snapshooting," as she calls it, helped her arrive at the perception that she must go beyond silent images to the slower voice of words.

"Mostly I remember things vividly," she says of the years she spent taking pictures. "I remember how people looked, just people standing against the sky sometimes, at the end of a day's work. Something like that is indelible to me. In taking all these pictures, I was attended, I know now, by an angel—a presence of trust.... It is a trust that dates the pictures, more than the vanished years."

Soon her stories started to come to her. Her very first, in 1936, was "Death of a Traveling Salesman," published in an obscure Ohio quarterly called Manuscript. When she was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship in 1942, she told a friend's aunt in Jackson her news. The aunt responded, "A Guggenheim what?" "I think she thought it was a hat," Eudora said.

By 1944 she had published A Curtain of Green and The Robber Bridegroom, and for six months of that year she lived again in New York City. Robert Van Gelder of The New York Times Book Review had interviewed her in 1942 and later offered her a job. "Can you imagine?" she remembers. "Of course, I immediately accepted and then phoned my mother in Mississippi. She was glad I'd found a job, because they weren't easy to come by during the war." But she was not entirely comfortable. "I didn't want to give a book a bad review. No matter what it is, it's a year out of somebody's life." She used the pseudonym of Michael Ravenna when reviewing war books, and when readers wrote to Michael Ravenna, she replied that he was away at the front line.

Always unabashedly stagestruck, Eudora could look outside her office window and see the performers she most admired arriving at rehearsals and performances. Mae West was rehearsing Catherine Was Great just next door and Eudora often slipped in the back to watch. "I'd watch during my lunch hour. Nobody seemed to mind. And I was in heaven."

In 1949, with a $5,000 advance on a new book and a second Guggenheim, she made her first trip to Europe and fell in love with Ireland, as southerners often do. She walked alone on its country roads and hid under hedges when it rained. One of her writing idols was Elizabeth Bowen, whom she visited in County Cork. Later, at Cambridge, she lunched with one of her own admirers, E. M. Forster, and became one of the few women to enter the hall of Peterhouse College. Eudora recalls, "They were so dear the way they told me: they said, 'Miss Welty, you are invited to come to this, but we must tell you that we debated for a long time about whether or not we should ask you.'"

Years later Eudora—with 29 other women, including Helen Hayes, Lauren Bacall, and Toni Morrison—was invited to become a member of the Players Club on Gramercy Park, the prestigious establishment for theater people. They were the first female members. "Let's invade them, girls," Eudora announced to the assembled companions at cocktail hour.

By 1955 she had published four short-story collections, a novel, and two novellas. For the next 15 years, with the exception of three short stories in 1963, 1966, and 1969, until the novel Losing Battles, there was silence. She was virtually unpublished. These were difficult years personally. Her mother had serious eye surgery, and as her complaints multiplied, her condition gradually deteriorated. Eudora had to take care of her; there were no others to do this except salaried outsiders. Eudora's brother Walter, six years younger than she, also became very ill at the age of 40 with heart problems compounded by arthritis. "I'm so ashamed of not producing anything," Eudora wrote Diarmuid Russell. "I should think all of my friends would have given me up."

Walter died in 1959. Eventually, Eudora was forced to put her mother in a nursing home in Yazoo City, nearly 50 miles away. Eudora drove there and back every day of the week for more than a year to read to her and help look after her. On the long drives she sometimes made notes for Losing Battles in a notebook propped on the steering wheel. Her mother and her other brother, Edward, died four days apart in 1966.

To help pay for the nursing home, Eudora had to take a job teaching a writing workshop at Millsaps College in Jackson. She had 16 talented students screened by the English Department. When the now famous writer called the roll for the first time, the students realized she was more nervous than they were. "We hadn't expected that," says John Little, who was one of the students and later became director of the writing program at the University of North Dakota. "We didn't know this was the first college class she ever taught. We didn't know she was intensely shy." After the roll call, she read Dylan Thomas's "A Child's Christmas in Wales." After the story, the students sat in stone silence. Eudora looked at her watch; they looked at theirs. Finally, Tom Royals—now a lawyer in Jackson-rescued the day. "Miss Welty," he said, "since this is the first class, we don't have to stay the whole two hours." Her sigh of relief was audible.

After a few classes they tried a more casual setting—a Sunday-night social at someone's house. John Little got there late; he was carrying a case of cold Budweiser on his shoulder. The hostess frowned at the beer and sent the young man to the kitchen with it. The stifling silence from the living room matched that of the classroom. "Anybody want a Bud?," Little shouted. "Please," came one small voice from the silence. It was Eudora's. "The sight of Miss Welty drinking that beer had the sound of ice breaking," Little says.

Eudora's closest friend, in almost every way a sister, was Charlotte Capers, who died two years ago at age 83. Charlotte, author of an essay collection entitled The Capers Papers, and a friend of my own family's, was a descendant of Episcopal bishops and Sewanee College presidents, and one of the brightest, wackiest women on earth. To each other they were "Cha-Cha," pronounced with a soft ch, and "Dodo," like the note. Once not long before her death when she and another companion were helping Eudora into a four-door sedan, Capers said, "Let's get Dodo ... into the fo'do'."

Up until fairly recently, Eudora drove an ancient Oldsmobile Cutlass, and the sight of her, barely able to see over the steering wheel, making her way to Parkin's Pharmacy to buy The New York Times, was as familiar as another picture we all have in our memories, Eudora's profile through the open windows of her second floor, as she sat at her writing desk. She always declared that her work made her happy and fulfilled. With short stories she always tried to get down a first draft spontaneously, often in a single day's work. "After that," she says, "I revised with scissors and pins. Pasting is too slow and you can't undo it, but with pins you can move things from anywhere to anywhere, and that's what I really love doing—putting things in their best and proper place, revealing things at the time when they matter most. Often I shift things from the very beginning to the very end. Small things— one fact, one word—but things important to me. It's possible I have a reverse mind, and do things backwards, being a broken left-hander."

Because of her health, Eudora has a hard time writing now. "My body doesn't help me anymore," she tells me, quoting a friend.

Eudora was a tall woman in her prime, but osteoporosis and a compression fracture in her back eight years ago have left their mark. She has arthritis in her hands and can no longer use a typewriter. Some years ago, the New Stage, a community theater group in Jackson, had a rummage sale. Eudora drove over in her old car and took a half-dozen handblown Czechoslovak Easter eggs and an old Royal typewriter in its original travel case. It was the typewriter her father had given her years before, the typewriter on which she had written her novels and stories since the 1930s. Jack Stevens, an actor, bought it for $10. Later he donated it to the State Archives.

She laments not having direct access to the written page as she once did, in the days when we all watched her working as we walked or drove past the house. Directly across the street from the Welty home was the music building of Belhaven College, and from the practice rooms the sounds of piano music would drift across Pinehurst Street, keeping her company through the long and solitary hours at the old Royal. "Though I was as constant in my work as the students were," she has written, "subconsciously I must have been listening to them, following them I realized that each practice session reached me as an outpouring. And those longings, so expressed, so insistent, called up my longings unexpressed. I began to hear, in what kept coming across the street into the room where I typed, the recurring dreams of youth, inescapable, never to be renounced, naming themselves over and over again."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now