Sign In to Your Account

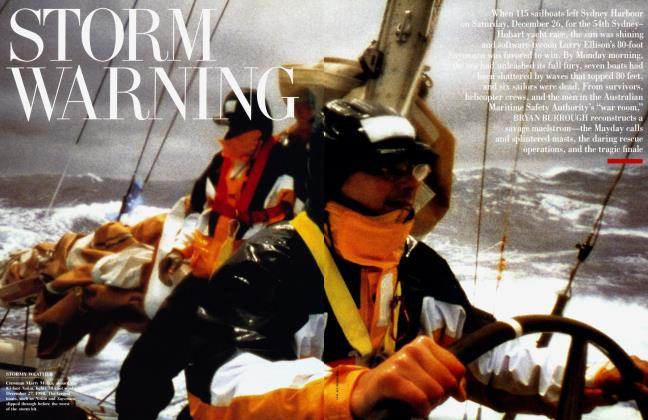

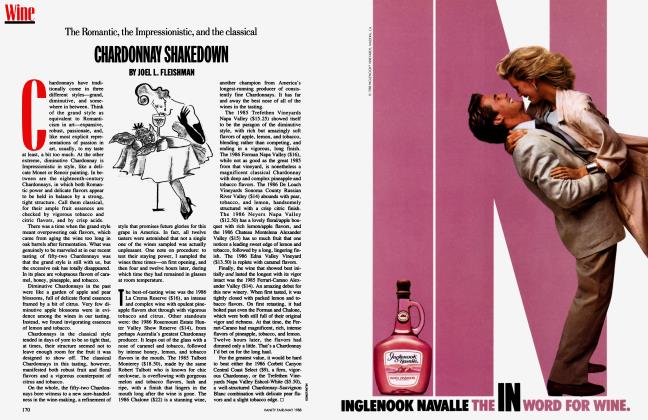

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE PENTAGON'S TOXIC SECRET

Thousands of American veterans suffer from debilitating Gulf War-related illnesses. But the origins have remained a mystery. A crusading molecular biologist and internal military documents now suggest a shocking scenario: the Pentagon's possible use on its own soldiers of an illicit and secret anthrax vaccine

GARY MATSUMOTO

Investigation

Veterinarian Dr. Herbert Smith negotiates the nine paces across his porch to the driveway of his house as though he were on a high wire, adjusting each deliberate step, shifting his weight from a walking cane in his left hand to another in his right. Smith lives in Ijamsville, Maryland, a subdivision no-man's-land of twoacre lots and empty vistas where the exurbs of Washington, D.C., commingle with those of Baltimore.

He wears black leather wrist pads Velcro'd from palm to forearm and a pair of ragged governmentissue elbow pads to protect himself from the falls he frequently experiences. "I'm subject to what's called neurapraxia—damage to the nerves," explains Smith. "Like with diabetics, who then wind up with amputations. I'm trying to avoid that."

On reaching the driveway, he straightens up to shake my hand. You can still see the outlines of the elite athlete he once was. Dr. Smith, 59 years old, is also Colonel Smith, Green Beret. His subordinates nicknamed him "Super Trooper," in deference to his gungho attitude and his once Olympian physique. When he entered airborne school at Fort Benning in April 1966 he set out to be No. 1 in a class of 687 by baiting his drill instructors to drive him harder than the others. "So, they targeted me. I must've done a thousand push-ups a day. But I knew it was all a game. I never got mad, never lost my cool. There were a couple of navy SEALS there. They were

"A doctor there accused me of bleeding myself to fake anemia/' says Colonel Smith.

pretty tough guys. But they weren't as tough as me." Until 1991, Smith ran P.T. (physical training) programs; the ones back in the 80s were notoriously grueling, earning him a nickname: "Dr. Death." He smiles at this but is unapologetic. "I wore 'em into the ground. In a fun way, not in a brutal way."

Today, a thick purple welt juts from Smith's forehead—an angry bulge from hairline to brow. Even on perfectly flat ground, he falls a lot.

The symptoms first appeared in January 1991, the same month, Smith says, that he got his first shot of something that does not appear on his immunization card or in his records—a mysterious vaccine, described to him only as "Vac A." He was then in Saudi Arabia training Kuwaiti medical personnel in disaster relief. Sometimes the pain was so bad in his right hand he couldn't hold a fork at meals. The next time it would be his left hand, never both hands at the same time. By May his joints ached and his lymph nodes were swollen, and he had a fever and a red rash on his chest and legs. He was constantly fatigued. It hurt to walk. It hurt to brush his teeth. After the invasion he wanted to stay on to help the Kuwaitis rebuild, but the symptoms were getting worse, and he had no idea what was wrong. He knew he needed treatment back in the States.

Just before he got on a transport heading home, one of his medical officers, who had seen similar symptoms in other soldiers, came up to him and said, "When you get home, check out the vaccines. I think you've got a problem with them." Smith had received vaccinations for hepatitis and tetanus, and a second shot of Vac A, which was entered into his records on February 14, 1991.

Back at Fort Meade, Smith was given a desk job while the military doctors investigated his condition—without success. In October 1991 he left active duty, but continued to see physicians at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. He didn't regard the problem as serious until the seizures started. Not grand mal, fall-on-the-floor, foam-at-themouth seizures, but complex partial ones, in which he appeared to be functioning normally but was actually on autopilot, without awareness of what he was doing. "I skipped periods of time," he explains. "I was in a car driving towards Baltimore on 1-70, and the next thing I know, I'm

outside of Washington, D.C., on 1-95, and I've got no clue how I got there."

One night, his worst, Smith became completely disoriented. "I had blacked out for an hour, hour and a half. I had to call my wife on the phone to find my way home. I was probably 25 miles away. I was an emotional mess because by then I had to admit to myself that something was wrong with me."

By this time Smith was seeing Dr. Michael Roy, an internist at Walter Reed. Roy diagnosed Smith's condition as "somatization disorder," a psychosomatic illness in which a patient becomes so obsessed with an imaginary disease that he begins to exhibit its symptoms.

Smith was not the only Gulf War veteran experiencing mysterious symptoms. In late 1991 and early 1992, some from a reserve unit at Indiana's Fort Benjamin Harrison reported sick with a constellation of symptoms that have since been associated with Gulf War syndrome: joint pain, headaches, fatigue, memory loss, and rashes. Reservists in Georgia and Alabama made similar complaints. Military doctors mostly dismissed the symptoms as psychosomatic or stress-related. As the number of people affected began to grow, several government studies were commissioned, including those of the Presidential Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses, the Institute of Medicine, and the Senate Committee on Veterans' Affairs. By 1996 all of them had concluded that there was no single disease that could account for all the different symptoms associated with Gulf War syndrome. The Department of Defense has examined at least 20 possible health hazards, including pyridostigmine bromide (P.B.) pills taken by the Gulf War troops to help protect against chemical warfare, the insect repellent DEET and various pesticides used by the soldiers, and Kuwaiti oil-fire smoke. A frequently repeated theory, still unproven, blames the syndrome on low-dose exposures to chemicalweapons fallout.

About 40,000 veterans have registered with the Department of Defense's Comprehensive Clinical Evaluation Program (C.C.E.P.) for Gulf War illnesses; another 70,000 or so are tallied by the V.A. A C.C.E.P. spokesperson says the numbers do not overlap; i.e., the total number of 110,000 to 115,000 is accurate. Of these, 18,000 are undiagnosed, and are merely being treated for their symptoms. To date, the federal government has sponsored 140 or so related research programs, exploring everything from microwaves to biological weapons, which have been funded at a cost to the taxpayer of more than $130 million.

Colonel Smith is one of the highest-ranking officers on full disability for Gulf War syndrome. He believes he might have never known the nature of his illness had it not been for the efforts of Dr. Pamela Asa, a Ph.D. molecular biologist who for the past five years has waged a one-woman battle with the Pentagon over the diagnosis of Gulf War syndrome and its cause. She has conducted her own research without a penny from the government or any other benefactor. Because of Asa's work, Colonel Smith has become more than a poster boy for a public-health disaster. Asa believes that in Smith's blood there is evidence that may hold the answer to why so many veterans of the Gulf War are sick.

Vanity Fair has uncovered military documents that show the Department of Defense made plans to run a clandestine trial of experimental vaccines and medical products during Desert Shield and Desert Storm. Military physicians called this effort "the Manhattan Project." While many of these vaccines were never used, Vanity Fair has found evidence suggesting that the Pentagon may have developed a modified version of its F.D. A.-licensed anthrax vaccine during an operation called "Project Badger." If Pam Asa is right, an experimental substance that causes incurable diseases in lab animals was mixed into an unknown number of doses—in essence creating a new, untested anthrax vaccine. The actual administration of such a vaccine would have violated the 10point Nuremberg Code, which in 1947 established the conditions for experiments on human beings—the cardinal point being informed consent. Speaking for the Pentagon, Dr. Ronald R. Blanck, a threestar general in the army's medical command, denies that any of this took place. "Absolutely not," he says. "I will tell you flat out it wasn't done."

T here are echoes of the antebellum I South in Pam Asa's accent, in the way I she can stretch three syllables out of a word like "hey." Her speech is a genteel drawl, evoking images of hoopskirts, silk fans, and magnolia blossoms. Asa, 46 years old and the mother of four, lives in Memphis, Tennessee. "American by birth, southern by the grace of God," she likes to say, especially in the presence of Yankees. During the Civil War, Union cavalrymen arrested her great-great-grandfather the Reverend John Murray Robertson for refusing to pray for Abraham Lincoln, and then turned his church, Huntsville, Alabama's Episcopal Church of the Nativity, into a horse stable. But though Asa is fond of making jokes about "the War of Northern Aggression," she is no regional chauvinist. Members of her family have fought in just about every American conflict, from the Revolutionary War up through Vietnam. Francis Scott Key, who wrote the words to the national anthem, is

"They're not going to equate my son with a lab rat," says Asa. "It's not right."

one of her ancestors. Her father retired from the Marine Corps as a captain in the early 1960s, then worked as a qualitycontrol director for NASA's Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville. Asa's reverence for the military borders on idolatry. "My father taught me ever since I can remember to have respect for anyone who serves in the military, because they protect us. They're willing to take bullets for us."

It was patriotism that motivated Asa to approach the Pentagon in 1994 about vaccines administered to the troops for Operation Desert Storm. By then, the symptoms related to Gulf War syndrome had been widely publicized. They were vague enough to point to anything from a stroke to allergies to mere tension. "But when these particular symptoms are taken together," Asa says, "they point to autoimmune disease"— when a person's immune system goes haywire and attacks his or her own body.

Mostly, doctors don't know what causes autoimmune disease. Many victims develop it from unknown causes. Since 1984, Asa had been working with her husband, Kevin—an M.D. certified in both internal medicine and rheumatology—to treat a

group of women with such autoimmune diseases as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. After a series of landmark legal cases in the early 1990s which alleged a relationship between silicone breast implants and autoimmune disease (the lawsuits put the main manufacturer, Dow Corning, into bankruptcy), a large number of the Asas' patients revealed that they had received breast implants. Pam Asa became convinced that silicone had induced diseases such as scleroderma and lupus in her patients—a conclusion that embroiled her in one of the most contentious public-health disputes of the 90s. It is a view that has propelled her into what promises to be an even more bellicose scrap.

Asa suspected that the autoimmune illnesses showing up in Gulf War troops were also induced by a toxic substance. For one thing, the gender breakdown of the victims was suspicious. Women develop autoimmune diseases far more often than men do. With lupus the ratio of female to male sufferers can be as great as 14 to 1. But among Gulf War veterans the victims were overwhelmingly male (an anomaly only partially explained by the

fact that women made up a mere 6.8 percent of the U.S. force serving there).

Another startling fact pointed to the vaccination program. Many of Asa's Gulf War-syndrome patients had never deployed to the Persian Gulf. They had never been exposed to petroleum fires, chemical-weapons fallout, pesticides, or the other suspected causes of Gulf War syndrome. But, she says, they did have one thing in common with the troops who were in theater: they had rolled up their sleeves and gotten their shots.

For Asa, all of this pointed to an adjuvant. Adjuvants are toxic substances which make vaccines more effective by stimulating an even stronger response from the immune system than a virus or bacterium might on its own. In the course of investigating the possible connection between her earlier patients' breast implants and their illnesses, Asa says she came across a confidential Dow Corning document showing that the company had conducted research with silicone as a vaccine adjuvant in 1974. The term "adjuvant" comes from the Latin word adjuvare, "to aid." But the quest for a safe, effective adjuvant has been like the medieval alchemist's quest to turn lead into gold. Adjuvants work because they are toxic, generally too toxic. Eighty years of research has produced a grand total of one that is considered safe for human use: a salt called aluminum hydroxide, also known as alum. Other adjuvants have been rejected as too dangerous; in tests on animals, adjuvants have been used over and over again to induce autoimmune disease.

At first, Asa suspected sabotage. "If the vaccine manufacturers were overseas, their loyalties could lie elsewhere or be bought for the right price." If an enemy wanted to undermine our fighting forces undetected, she says, this would be one way to do it. "I can't think of a more effective and insidious way to reduce the effectiveness of a military force going into combat. This disease process affects people's minds. Patients suffer mood swings, blackouts, and cognitive disorders where a person loses the ability to read or understand language or remember directions. This is not what you want to see happening to people who handle guns, bullets, and bombs." Asa contends this "process" can develop into full-blown, debilitating, and sometimes fatal autoimmune diseases such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis.

"I would have declined to give the vaccine. Ybu do not obey an unlawful order."

In June 1994, Asa phoned Colonel John Dertzbaugh of the Pentagon's Defense Science Board with her theory. Dertzbaugh said it made a lot of sense, and promised to check it out. But the Science Board had just completed a report concluding that there was "no persuasive evidence" of Gulf War syndrome and no single cause of illness related to service in the Persian Gulf. The report had gone to press, and no one wanted to reopen the investigation. Still, Dertzbaugh couldn't shake the feeling that it was important to give Asa's theory a closer look. In December 1994, he asked her to write a report and submit it to the Office of the Army Suigeon General. Dertzbaugh even made a personal pitch; he told the office that Asa's theory appeared to explain the patients' problems, as he understood them. Asa says she asked the office for vaccine samples to test free of charge—to no avail.

Herb Smith didn't call Pam Asa. She called him. In March 1995, 60 Minutes ran a segment on Gulf War syndrome that made a case for chemical weapons as its cause. Promoting this view was one of the veterans whom newsman Ed Bradley interviewed, Colonel Herbert Smith. "We were getting hammered with a lot of information about us getting affected by chemicals. I was getting sick enough where I couldn't argue with anyone. As you noticed," Smith recalls now, "they were talking about chemicals. [Former] senator Don Riegle [Democrat, Michigan], his team, and Jay Rockefeller [Democrat, West Virginia] and his team—they all said it was chemicals."

Watching the program, Asa noticed that Smith's knuckle joints had a particular swelling that she had seen before. She was convinced he had an autoimmune disease.

Asa decided to track down Colonel Smith. "60 Minutes called me and said, 'We got people calling and they wanna talk to you,'" says Smith. "And I said, 'Fine, you know, doesn't bother me, let 'em call.' I was getting people calling me up and saying, 'You've got Lyme disease; you've got chronic fatigue syndrome; you need to take vitamin C.' They were trying to help, but they were nuts. When Pam called, I thought, Well, here's another one gonna tell me, you know, what I've got and how to fix it. And then she starts talking and it just makes sense to me." About one month later, Smith says, he flew to Memphis to be treated by the Asas.

After examining Smith, Dr. Kevin Asa agreed with his wife that the diagnosis was systemic lupus erythematosus (S.L.E.). Physicians back at Walter Reed balked. Smith recalls them protesting, "You can't have lupus! You're a white male in your 50s. People like you don't get autoimmune diseases!" They refused to run their own tests. Smith was not surprised at this response from the people who had been telling him that his problems were all psychological. "I had a doctor there, a guy named Michael Roy [major, U.S. Army]. He accused me of bleeding myself to fake my anemia," says Smith. "I have a degree in chemistry as well as being a doctor of veterinary medicine. Anyway, he says I'm a pretty smart guy, so I must know how to screw up my lab results." (Dr. Roy could not be reached for comment.)

Smith wouldn't let this insult go. "I wrote a letter to the commanding general, and I told him I had an officer, a major, accuse a superior officer, me, of conduct unbecoming an officer, and perjury. They gave me this new doctor, and he comes in saying, 'Well, you know, Dr. Roy says you got all these psychological problems.' And I said, 'What about all the V.A. findings [which supported the conclusion that Smith was physically ill]?' 'The V.A.? They're wrong. They don't know what they're doing.' So I asked, 'If you won't believe the V.A., who will you believe?' And this new doctor says, 'We'll believe either N.I.H. [National Institutes of Health] or Johns Hopkins.'"

Smith sent his lab results to the N.I.H.'s Dr. John Klippel, who had co-edited a standard medical-school text in this field called Rheumatology. "He reviewed the case," says Smith, "and he said the Asas' diagnosis was correct, but he couldn't see me, because he wasn't accepting new patients." (Dr. Klippel could not be reached for comment.) Smith then sent his records to another leading rheumatologist, Dr. Michelle Petri of Johns Hopkins University Medical School. "She called me up and said the Asas' diagnosis was correct, but she's going to have to run her own tests to confirm this. I gave more blood. Did a brain scan. And the results were pretty much the same."

When the Asas treated Smith for lupus, his pain subsided. He could get out of his wheelchair and walk again, provided he used canes.

Word about Asa had spread on the Internet's Gulf War-veteran grapevine, and others started to get in touch with her. One was Dr. Charles Jackson, a general practitioner who used to work at the V.A. hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama. Jackson told her he had hundreds of Gulf War-syndrome patients; he didn't know what it was or how to treat it. Asa asked him to run standard diagnostic tests for autoimmunity. Jackson says the lab values suggested that a full quarter of his Gulf War patients had autoimmune problems.

But if Gulf War syndrome is adjuvantinduced autoimmunity, what is the adjuvant? In 1995, Asa got the clue she sought. An official with the Senate Committee on Veterans' Affairs introduced her to a patient who had volunteered for an N.I.H. experimental-herpes-vaccine trial. The patient complained of chronic fatigue, muscle and joint pain, headaches, and photosensitive rashes—the same baseline symptoms as in Gulf War syndrome. She also had arthritis and other autoimmune disorders, diagnosed through lab tests. But this particular patient had never received the herpes vaccine. She'd been injected with a placebo, a single shot of a compound called MF-59, which contained an adjuvant that is much stronger than alum: squalerie. This was in 1991, the same year as Desert Storm. Asa discovered from published scientific papers that squalene was a cutting-edge adjuvant used in at least three experimental vaccines in the 1990s. These were used in tightly controlled experiments on animals and humans, but vaccines containing squalene have never been approved by the F.D.A. for human use.

O qualene is a lipid, or fat, that can \ be found in sebum, an oily subU stance secreted by the human sebaceous glands. Commercial squalene is extracted from shark livers. You can buy it in health-food stores in capsules which are purported to boost the immune system. It is also used in some cosmetics as a moisturizing oil. Squalene manufacturers say it's safe, and it appears to be when swallowed or rubbed on the skin. But injecting it is another matter. The adverse effects of vaccines containing squalene have been documented in papers published in such peer-reviewed scientific journals as Vaccine and the Annals of Internal Medicine. Since the mid-1970s researchers studying autoimmunity have used squalene to induce rheumatoid arthritis and a multiple-sclerosis-like disease called experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (E.A.E.) in rats. Like every other oil-based adjuvant ever concocted, squalene is apparently unsafe.

"For almost 20 years I held a top-secret clearance. Suddenly I'm psychotic?" says Swan.

A rheumatologist who conducts research into adjuvants at the N.I.H. disputes the idea that adjuvants can induce autoimmune disease in humans. The researcher, who did not wish to be named, calls these allegations "junk science." He admits that squalene can induce rheumatoid arthritis, but alleges that it does so only in one species of rat. Published scientific studies, however, show that squalene has been linked to the development of autoimmune disease in rats, mice, and macaque monkeys. When asked if he thinks the F.D.A. will ever approve squalene as an adjuvant, the N.I.H. researcher says no. "The F.D.A. has not had a track record of approving oil-based adjuvants."

Research with squalene has been done at Stockholm's Karolinska Institute, which names the finalists for the Nobel Prize in Medicine each year. Dr. Lars Klareskog, a rheumatologist at the affiliated hospital, concurs that compounds with squalene could be dangerous for humans. "It's true that adjuvants can, in these experimental models, turn a potential autoimmune reaction that is otherwise not pathogenic into pathogenic immune reactions. That is true in experimental animals. Whether that is true in humans, we do not really know. But we believe that is so. Where the event occurs in reality very much depends on the genetic background."

I n early 1995, Asa submitted to the army I surgeon general the report Dertzbaugh I had asked her to write. In response, the Department of Defense in March 1996 published a report on the Internet, refuting her theory without ever putting it to the test. A letter to the commander of the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command from Dr. Walter Brandt, who works for the Science Applications International Corporation, a Pentagon contractor, summarized the army's critique of Asa's theory, claiming that the only adjuvant the military used in vaccines was alum. He also criticized Asa's use of the phrase "human adjuvant disease" (H.A.D.), a term used by Japanese doctors in the 1960s to describe autoimmune problems in women who had received silicone injections to enlarge their breasts. Brandt's letter said, "The term was coined 30 years ago and is generally not used by most informed physicians today_There is similarity between H.A.D.

and Gulf War Syndrome in their symptomatology. However, the development of symptoms in H.A.D. requires years, not months."

After the Internet report came out, Asa's initial frustration with the army's lack of response turned to anger. "Adjuvant disease doesn't take years to create symptoms," Asa says. "And I wrote them about squalene and they hardly mentioned a word about it." Recently, Dr. Brandt explained to Vanity Fair, "The presence of squalene or squalene antibodies in blood samples would seem to be a natural occurrence and not an indicator of adjuvant injection." According to Dr. Robert Garry, a professor of microbiology at Tulane University School of Medicine who works with Asa, this contradicts the fundamental definition of autoimmunity. "If that were true, we'd have antibodies to all the proteins, all the tissues in our bodies, and the immune system wouldn't function at all," he says.

In August 1997, Vice Admiral Harold M. Koenig, then the surgeon general of the navy, wrote that the army "has used squalene as an adjuvant in several experimental vaccines ... over the past ten years_

Military members who served in the Persian Gulf received standard vaccines, licensed by the FDA, with one exception [botulinum toxoid, which approximately 8,000 troops received].... Squalene was not a component of any vaccine product given."

In June 1996, after denying for years that Iraq had ever forward-deployed chemical weapons during Desert Storm, the Defense Department admitted that the U.S. had destroyed a large cache of chemical munitions at the Khamisiyah depot in Iraq in March 1991. Using only limited data on weather and detonation patterns, in 1997 the D.O.D. and C.I.A. released computer models of a toxic plume emanating from Khamisiyah, wafting downwind and possibly contaminating 100,000 troops—by remarkable coincidence the approximate number of veterans who at the time were believed to be sick. (In September 1998, after conducting its own study, the Senate Committee on Veterans' Affairs would censure both the D.O.D. and C.I.A. for faulty analysis and for sending letters to Gulf War vets suggesting—without sufficient evidence —that Gulf War syndrome may have been due to fallout from Khamisiyah.)

The Khamisiyah computer models were suspect, but the spin was effective. The C.I.A.-produced animations were played and replayed on television news shows. Almost overnight, chemical-weapons contamination became the conventional wisdom on the cause of Gulf War syndrome. Saddam did it, sort of. So did the wind. And maybe army engineers should have taken more precautions. As shots in the dark go, this seemed to make sense. The appearance that the Pentagon and C.I.A. had disclosed a possible cover-up lent the idea credibility.

"All I know is, my son and other people are getting sick after getting the anthrax shots."

But even if a toxic plume had actually existed and moved in the direction the Pentagon said it did, enveloping 100,000 troops with minute doses of nerve agent, the theory collapses on several points with regard to autoimmune disease. First, the symptoms don't match: the effects of chemical weapons—acute headache, nausea, shrinkage of the pupils to pinpoints, and muscle paralysis—are well documented. In more than 50 years of data on nerve gases, published since the Nazis invented the chemical weapons sarin and soman, there isn't a single recorded instance of a nerve agent causing autoimmune symptoms or diseases.

Second, veterans suffering from the symptoms of Gulf War syndrome who never deployed to the Gulf could not have been exposed to chemical-weapons fallout, or any other toxic agent in the region. Some of the veterans never left the United States; some went to other countries, such as Egypt. These veterans did not take P.B. pills. Moreover, had chemical weapons caused Gulf War syndrome, one would expect to see it among those who are native to the region. Yet according to U.S. defense intelligence documents, there are no reports of Gulf War syndrome among the Kuwaitis or Israelis. The Egyptians, who contributed some 40,000 troops to the coalition force, don't have it; neither do the French or the Belgians. All of them sent troops. Another cohort of people who do not significantly report cases are the journalists who covered the war, myself included. These groups all have at least one thing in common: they did not receive shots for biological-warfare agents.

Retired air force master sergeant Jeffrey Swan, 40, says he got his shots at Fort Belvoir in Virginia sometime around March 1991. Only one of the vaccines he received was identified (smallpox), so he doesn't know which other shots he was actually given. Because Swan speaks Arabic, French, and Greek, the air force sent him to Egypt in April 1991 to serve as a liaison with the Egyptian military. About four months later the tremors started, which made him look as though he were suffering from an alcoholic's D.T.'s. He developed joint and muscle pain and experienced seizures similar to Smith's. In 1996, back home in Tamworth, New Hampshire, he felt his car accelerating out of control and he slammed on the brakes. But it wasn't moving; he was parked at a shopping center.

Swan's symptoms were the same as those of veterans who had Gulf War syndrome, but a V.A. physician refused to put him on the government registry for it. "He told me that I had Gulf War illness, but he couldn't write that in the records, because I hadn't been deployed there, I wasn't in the right place. So he wrote 'undiagnosed illness.'" Air-force physicians have listed Swan's problem as "Major Depression with psychotic features." "For almost 20 years I held a top-secret security clearance," Swan says. "On my medical chart there was a big red-and-white sticker that said, 'SENSITIVE DUTIES.' I never had a doctor or dentist once note anything suspicious about my behavior. Any hint of instability had to be reported immediately.... Anything that might affect my performance had to be reported, even a teaspoonful of codeine. Suddenly I'm psychotic?"

Swan thinks he knows why he and other veterans have encountered this penchant to call their problems psychosomatic, if not psychotic. "Anything I said could be dismissed. It got to a point where / didn't even believe I was having these symptoms ... that I was imagining everything. If we were registered for Gulf War syndrome, then everybody would know that the sickness couldn't be due to chemical weapons. We're the proof." According to Asa's reading of Swan's lab tests, Swan has lupus. He says a V.A. rheumatologist also told him that he may have atypical lupus, but that it would take more time to confirm the diagnosis. Asa has tested Swan +2 positive for squalene on a scale of 4.

In early 1997, Asa bought 200 milliliters of squalene from Acros Organics in Geel, Belgium. She developed a scratch test to measure sensitivity to the substance. All 10 of her Gulf War patients were "reactive." Some suffered symptoms such as rashes or swelling at the injection site. She also tested a control group of healthy patients who had never taken military vaccines; none of them reacted. Still, Asa didn't have her evidence. The scratch test indicated exposure, but didn't prove squalene had been injected.

Around this time, Asa teamed up with Robert Garry at Tulane University. Garry and the university received a U.S. patent in 1997 for an assay that could detect antibodies to polymers, of which squalene is one. Asa sent Garry an initial batch of serum samples, including one from the subject who had volunteered for the N.I.H. herpes-vaccine trial. Asa didn't tell Garry which polymer he would be testing for, or which patients might have been exposed to it. This would be a blind study.

When the samples all came back positive for antibodies to the unknown polymer, Garry repeated the tests and got the same results. He also tested frozen serum samples from Gulf War veterans sent directly to him in 1993 by Department of Defense and V.A. researchers. He had originally been asked to test the blood for evidence that the patients had been exposed to retroviruses including H.I.V., for which they were virtually all negative. Garry got these samples out of cold storage and ran the new assay on them. He had been told that some of the samples were from healthy control subjects; now 69 percent of the samples tested positive for antibodies to the unknown polymer.

It was at about this time, Asa says, that the phone calls started. She would answer the phone, and no one answered back. Her phone would occasionally dial 911 by itself in the middle of the .night. A year and a half earlier, just after she had submitted her report to the D.O.D., there had been two attempted break-ins at her house. Her husband opposed any further involvement with the Gulf War-syndrome patients after the harassment began. If it was tied to this work, their children could be in danger, he believed. But Asa persisted, partly, she says, for the safety of her children. Her eldest, Chris, was in high school and would soon register for the draft. "They're not going to equate my son with a lab rat. I don't care what the vaccine is. I don't care what they claim it's supposed to do for mankind. It's not right to experiment on people, ever."

"Our commander told us to destroy everything connected with the vaccine/'says Dr. Dubay.

Asa sent Garry more samples, and by the fall of 1997, Garry had the results. Ninety-five percent of Asa's Gulf Warsyndrome patients had tested positive for antibodies to the unknown polymer. Colonel Smith was positive. The subject from the N.I.H. vaccine trial was positive. Of those sick veterans who had never deployed to the Gulf, but who said they had received shots, 100 percent were positive.

In all, Asa and Garry tested some 350 subjects, half of them controls. "So what was that stuff?" he asked Asa.

"Squalene," she said.

This left one major question unanswered. If the military used a squalene adjuvant, in which vaccine did they use it?

In August 1990, the month Iraqi troops invaded Kuwait, there was palpable anxiety at the Pentagon over the prospect that Saddam Hussein might use biological weapons to defend his newly annexed territory. On August 8, intelligence intercepts of Iraqi military communications indicated that Baghdad had produced and probably weaponized (i.e., made suitable for warfare) many deadly biological agents, including botulinum toxin and anthrax. The U.S. Army had been purchasing small amounts of vaccine for both, but its stocks were woefully short of what would actually be needed. A high-ranking army source confirms that by August 1990 the United States had stockpiled between 11,000 and 12,000 doses of anthrax vaccine. We eventually deployed 697,000 troops in the Persian Gulf.

According to declassified military documents, in August 1990 the army surgeon general at the time, General Frank F. Ledford Jr., ordered a team of doctors and researchers from the army, the navy, and the air force to form a secret Tri-Service Task Force on vaccinations for troops in the Gulf. On October 9, 1990, in a conference room at the army's Fort Detrick in Frederick, Maryland, the Defense Department

convened the first meeting of the task force, which began to draft plans to "surge" the production of vaccines for anthrax and botulinum toxin. At the next meeting, on October 12, the acting chairperson, Colonel Garland McCarty, and a team of 13 other officers decided to give the task force and its mission the code name Project Badger.

Of more than 160 companies that were asked to make anthrax vaccine, all but one said no. Only Lederle-Praxis Biologicals of Pearl River, New York, signed on. Under the supervision of General Ronald R. Blanck and Colonel Harry Dangerfield, Project Badger organized the production of additional anthrax vaccine at the National Cancer Institute's Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center, located at Fort Detrick. Both Lederle and N.C.I. were unlicensed and unregulated by the F.D.A. The plan called for subcontractors to ship vaccine to the only F.D.A.-licensed manufacturer of anthrax vaccine, Michigan Biologic Products Institute (now BioPort), in Lansing, Michigan, for bottling, labeling, potency testing, and storage. This would have been another breach of federal safety regulations. As an earlier task force memo from October 10 stated,

"It must be noted that any firm other than Michigan will produce a vaccine under an I.N.D. and not a licensed product." I.N.D. stands for "investigational new drug," which requires special approval from the F.D.A. for use. The army—as the executive agent for the Defense Department's biological-warfare vaccine program—should have sought that approval. It did not, and N.C.I. confirms that it never applied for an I.N.D. to produce anthrax vaccine. (Wyeth-Ayerst International, which now owns Lederle-Praxis, could not be reached for comment.) The F.D.A. must approve all vaccines used in the United States and also license the production sites, military vaccines not excepted. General Blanck disputes this scenario unequivocally. "I have no knowledge of anybody producing any anthrax vaccine other than Michigan," he says. "Nobody provided us or produced any vaccine, because the war ended, basically, is what happened."

By the first week of December 1990, Project Badger had begun plans to test If other experimental vaccines on U.S. troops in the Gulf. Project scientists referred to this endeavor, rather portentously, as a "Manhattan-like project," or simply a "Manhattan Project." They organized a crash program to manufacture, or purchase, at least four experimental vaccines: Enterotoxigenic E. Coli, Hepatitis A, Centoxin, and Shigella. At least two other experimental products were ultimately used: P.B. pills and botulinum toxoid vaccine, for both of which the army received from the F.D.A. a waiver of informed consent.

As for the mysterious "Vaccine A," variously cited as Vac A, Vac A-l, or Vac A-2 in the shot records of sick veterans such as Colonel Smith, declassified Defense Department documents identify it as anthrax vaccine. Dr. Gregory Dubay, who commanded the 129th Medical Company, a former Alabama National Guard unit out of Mobile, gave thousands of anthrax vaccinations to troops. He says, "Each soldier had to read a classified sheet of instructions, stating that he, or she, was receiving a secret shot, and that this was so for reasons of operational security. You don't want to tell the enemy that you're getting protection against one of his weapons." Dubay—who both administered and took the vaccinations—says that he was under orders not to record the inoculations in the soldiers' medical records, and that the troops were not given a chance to de-

"No one in their right mind would volunteer for something like that/' says Jeff Rawls.

cline the shots. "You were just marched through, and that was it.... Then our commander told us to destroy everything connected with it—the empty vials, the boxes, and the package inserts. We burned them all in 55-gallon steel drums back behind the tents."

The Pentagon says that 150,000 Gulf War troops received anthrax inoculations. There are no documents available proving that the army used a squalene adjuvant in the unapproved vaccines, and the army has specifically denied it. But that still leaves Asa and Garry with more than 100 sick veterans who had their shots and now test positive for antibodies to squalene.

Why might the army have used squalene instead of alum, the only adjuvant approved for human use? Probably because squalene was stronger. The licensed anthrax vaccine was relatively weak. Immunity wasn't achieved with one shot. It took six shots, administered over a period of 18 months, then an annual booster. In 1991, tens of thousands of U.S. troops arrived in Saudi Arabia only a month before the coalition forces began the ground war. Most could get only two shots out of the six-shot regime; some just got one. And there was, perhaps, an even more compelling reason to enhance the vaccine. Two former members of Project Badger say the coalition suspected that Iraq had engineered a more powerful anthrax bio-weapon. "We were concerned that Saddam may have made anthrax resistant to penicillin," says one, who does not wish to be identified. "We knew he had the skills to do that—people who had trained in the United States, who had the skills to turn the bug into a resistant bug.... The Brits were the ones who gave us the information, actually. We actually knew who those people were." The anthrax vaccine licensed by the F.D.A. back in 1970 was designed to protect against anthrax germs that occasionally infect woolsorters and veterinarians. It was not known to be effective against a biowarfare agent that Iraq had possibly made more lethal. It is plausible that the army thought an experimental anthrax vaccine was worth the risk, especially since squalene was considered to be a superior adjuvant. However, this was a hypothesis. Administering such a vaccine to the troops would have been tantamount to a human experiment. In order to conduct a legal trial with squalene, one would have to file an "investigational new drug" application with the F.D.A. and have that application approved. This did not happen. In October 1997, the British revealed their attempts to boost the efficacy of their anthrax vaccine during the Gulf War by using a pertussis vaccine as an adjuvant. This controversial combination had caused serious side effects in animals. But Asa believes she has evidence that the British also boosted at least one of their vaccines with squalene. In 1998, she tested five British veterans suffering from symptoms similar to those of Gulf War syndrome. Four were positive for antibodies to squalene. (The British Ministry of Defence denies using squalene in vaccines given to Gulf War troops.)

Among the 1991 coalition allies, the United States, Britain, Canada, and the Czech Republic have reported possible Gulf War-related illnesses. Of these, the first three admit to immunizing troops against biological-warfare agents.

Production of anthrax vaccine in unlicensed facilities did not end with the war. On August 29, 1991, six months after Iraq's surrender, the army surgeon general approved a $15.4 million contract for a company called Program Resources, Inc. (P.R.I.), a National Cancer Institute subcontractor that managed some of N.C.I.'s labs at Fort Detrick. Contracts were drawn up for fiscal years 1992 and 1993. In a secret Pentagon log kept continuously between August 8, 1990, and February 7, 1992, there are numerous references to the army's expanded vaccine-production program, but no record of any decision to halt it or to cancel the contract with P.R.I. Chuck Dasey, a spokesman at Fort Detrick, says that no anthrax vaccine was ever produced through the contract.

Presumably, the vaccines made during the Gulf War are part of the stockpile I now being administered in the wake of the D.O.D.'s December 1997 decision to immunize all 2.4 million people in the armed services against anthrax. When Pentagon officials held a press conference about the mandatory immunizations last summer, they insisted that there had been only seven reported adverse reactions to the nearly 140,000 anthrax vaccinations that the military had given in the preceding six months. But according to the F.D.A.'s Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, there were at least 64 reports of reactions to the vaccine between September 2, 1998, and March 9, 1999. Activist Lori Greenleaf, a day-care provider in

Morrison, Colorado, says that, based on her E-mail, there are a lot more military personnel reporting problems. Greenleaf began a grassroots campaign against mandatory anthrax immunizations because of her 23-year-old son, Erik Julius, who she says fell ill after taking the second of three anthrax shots in March 1998. She is swamped with messages from fearful enlisted men and women. Some of them have already received their anthrax shots. "They've got rashes, chronic fatigue, hair loss, memory loss, muscle and joint pain, numbness in their extremities." Greenleaf says she does not know what an adjuvant is, and she has no idea what is ailing her son. "All I know is, my son and many other people are getting sick after getting the anthrax shots, and it sounds an awful lot like Gulf War syndrome."

Two servicemen who received their anthrax shots last year have tested positive for antibodies to squalene. One received vaccine from Lot No. FAV020, the same lot sold to Canada and Australia. The other serviceman received vaccine from Lot No. FAV030. Doses from this lot were also sold to Canada, according to that country's Department of National Defence. There is no evidence that every dose in FAV020 and FAV030 is contaminated with squalene, but the antibodies in these two veterans suggest that anyone immunized from these lots may be playing "vaccine roulette." The U.S. has shipped anthrax vaccine from other lots to Germany, Israel, and Taiwan.

If the first casualty of war is truth, then the rule of law is a close second. As Cicero wrote, "Laws are silent in time of war." In the fall of 1990, the Pentagon began petitioning the F.D.A. to waive informed-consent requirements on so-called investigational new drugs for the Persian Gulf. This was an ethical powder keg. In 1947, under the authority of the U.S. military in Nuremberg, Nazi scientists and physicians stood accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity for performing experiments on prisoners. Seven were hanged. Following the trials, U.S. judges drafted the 10-point Nuremberg Code, which was intended to govern all future experiments involving human subjects. The code's first and bestknown principle was voluntary, informed consent. Until the Gulf War, the U.S. military had never argued that there should be any exceptions. In the end, the F.D.A. de-

Production of anthrax vaccine in unlicensed facilities did not end with the Gulf War.

cided to grant waivers for P.B. pills and for the rarely used and as yet unlicensed vaccine botulinum toxoid.

In 1994, the Senate Veterans' Affairs Committee called this a violation of Nuremberg, the moral equivalent of the army's World War II-era mustard-gas tests on troops and its LSD experiments in the 50s and 60s. "We'd like to think these kinds of abuses are a thing of the past, but the legacy continues," said the committee chairman at the time, Senator Rockefeller. "During the Persian Gulf War, hundreds of thousands of soldiers were given experimental vaccines and drugs ... these medical products could be causing many of the mysterious illnesses those veterans are now experiencing." Rockefeller could barely contain himself: "The D.O.D.'s failure to provide medical treatment or information to soldiers was unjustifiable, unethical, sometimes illegal, and caused unnecessary suffering."

He was referring to the experimental PB. pills and botulinum-toxoid vaccine. Rockefeller and his staff made no mention of unapproved anthrax vaccine, Project Badger, or the Persian Gulf "Manhattan Project."

Declassified documents show that Dr. Walter Brandt, who helped oiganize the Internet report attacking Asa's theories, was one of the original members of Project Badger. Dr. Michael Roy, the physician who diagnosed Colonel Smith's illness as psychosomatic, also worked with members of the team in early 1991—the same doctors who planned the "Manhattan Project." The Pentagon says that most of the unit logs in which biological-warfare vaccinations were recorded are missing. Vanity Fair has found an army document showing that at least some of these records were ordered sent to the Office of the Surgeon General. General Ronald Blanck, who led the Project Badger Working Group on expanded vaccine production, is the current army suigeon general.

Some might understand the decision to accelerate vaccine production by any means possible when faced with the prospect of biological warfare. But Dr. Greg Dubay believes he should have been told if he was administering an altered version of an existing vaccine. "If I'd known it was a vaccine that had been tampered with—if it was tampered with—I would

have declined the order to give it," he says. "You do not obey an unlawful order. If I knew it was done clandestinely, and had solid evidence, I would have disobeyed the order. The first oath of every physician is to do no harm. I don't know any physician who would purposely do something that is truly harmful, unless you're a Mengele or something."

A spokesman for BioPort says parts of Project Badger remain classified. Pentagon officials deny using a squalene adjuvant in any Gulf War vaccines and balk at Asa's allegation that some undiagnosed Gulf War illnesses are autoimmune diseases. Can a substance that induces autoimmune disease in a rat or a mouse be dangerous to a human being? Former Marine Corps tank commander Jeff Rawls has a solution for the naysayers. Rawls is a 31-year-old Gulf War veteran who now lives with his parents in upstate New York. He has experienced severe shrinkage of part of his brain and can barely walk. At +3, he is almost off the scale for antibodies to squalene. "Inject them with the same thing and see what happens," Rawls says in a slurred and halting voice. "No one in their right mind would volunteer for something like that."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now