Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLET US NOW PRAISE WALKER EVANS

Art

MOMA rediscovers a neglected photographic masterwork

MARK STEVENS

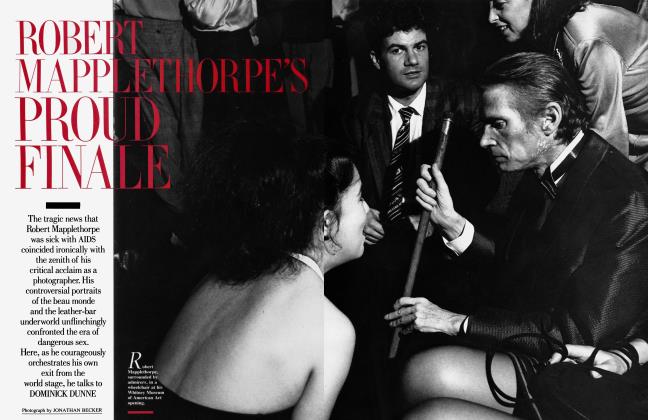

Photography itself has become a kind of celebrity— the belle of the eighties ball. For most magazines it now provides the indispensable snap, crackle, and pop; critics, in turn, regard the camera's invention with the awe once accorded the development of printing. (This year the museums will celebrate the 150th birthday of photography with some big, bragging exhibitions.) Much serious photography also looks surprisingly tony. At the Whitney Museum last fall, Robert Mapplethorpe's silky pictures of celebrities, flowers, and sadomasochists caused much talk. In the galleries, some photographers best known for fashion and

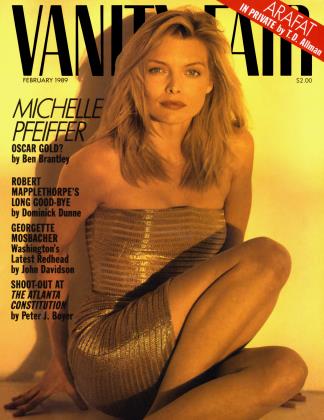

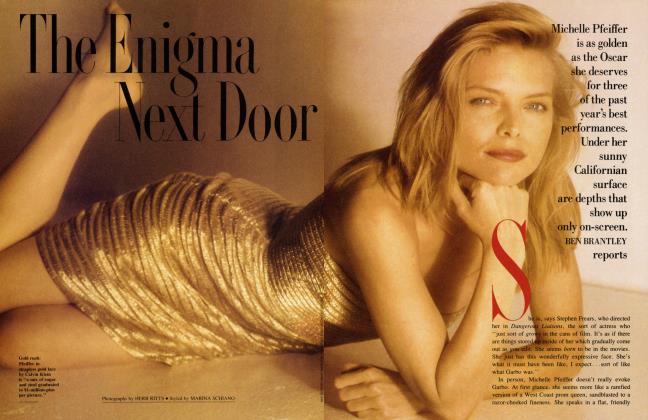

celebrity work, among them Bruce Weber and Herb

Ritts, announced themselves as serious artists.

A certain slicked-up fanciness is one of photography's charms, and "crossover"

artists from fashion (and journalism) have regularly refreshed the medium. But stylishness today often seems suffocating, too polished, too done up, too much. Such a fuss about gym-molded bodies, razzle-dazzle printing, zowie compositions. So many pretty ugly people and pretty pretty people. Photographs are turning into perfume. Those who prefer a strict eye and a cool intelligence, who welcome the slap of truth, will be getting bored. It is for such people, perhaps, that the Museum of Modem Art is now honoring a truly strong photographer—and a great American artist.

The museum has just reissued American Photographs, the masterpiece of Walker Evans. (The book, based on a 1938 exhibition at MOMA, contains an essay by Lincoln Kirstein, and the curator Peter Galassi has assembled many of the original photographs for a show at the museum.) Unfortunately, Evans (1903-75) is much better known for another book, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, his Depression-era collaboration with James Agee about a sharecropper family in the South. That particular pairing was certainly inspired—Agee brought the fire, Evans the ice—but it has led to a vulgar view of the photographer as a champion of the downtrodden. Although social compassion informs Evans's work, I think he cared as much for buildings as for people. Pity alone never made a poet.

Evans came from a prosperous midwestern family and went to Andover. He dropped out of Williams College at the end of his freshman year, hoping to become a writer. Eventually he went to Paris (no, he wasn't raising a glass with Ernest and Scott). He later told an interviewer that "I wanted so much to write that I couldn't write a word." He especially admired the exacting eye Flaubert turned upon the world and its desires. When Evans took up the camera, he turned his back on the glamour of the moment, disdaining both fashion photography and the arty ambitions of Edward Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz. Instead, he began to record indigenous American architecture, and from 1935 to 1937 worked for the Farm Security Administration, documenting rural poverty. Much of his later life he spent creating photo essays for Fortune, and he ended as a bearded presence at Yale, criticizing whatever was soft and mushy in photography.

It was in the 1930s that Evans had his great run, and it is American Photographs that established him as a great artist. Strangely enough, this essential book has been out of print for years and, except to photographers, remains too little known. People have often spoken longingly of "the great American novel." In this slim book, Evans attained what the writers have looked for. Nearly half of the photographs stemmed from Evans's work for the Farm Security Administration, but the book has a concentrated poetry that goes well beyond the purely documentary. Evans was a Yankee with a puritan's disdain for showing off. He revered the hard bite of fact, but, like the best puritans, he also sensed the shadow of passing angels. Because he could discern what Kirstein called the "revelatory fact," he gained a privileged perspective on the lovers' quarrel between the American dream and the American reality.

Evans divided his book into two parts, the first mostly pictures of people, the second mostly of houses—a map of American faces and of American expressions. Although the faces come in many colors and shapes, Evans did not arrange them into that typical American heart-warmer, the ethnic rainbow; nor did he present the opposite, a cynic's revision of the cliche. The face of each dockworker, farmer, and lover remains irreducibly particular, so that Everyman is never less than someone. Typical national poses are struck. An American Legionnaire, for example, shoots the camera a cocky look— but his forehead puckers slightly with selfpity, and his mustache is that of a dandy.

Evans collected examples of vemacular art as if it were an endangered L species: a bit of folk painting on the side of a wagon, a peeling poster for a minstrel show, an artful display of tires or watermelons beside the road. American houses especially excited him. They seemed to embody the wit, pride, and dreams of ordinary people, as in the sweet formal fuss of carpenter's gothic or the baronial pride of a decaying boardinghouse. Evans's houses are very nearly alive; Kirstein rightly referred to the photographer's pictures of people and portraits of houses. It is all the more affecting, then, to see so many of these houses (and other folk art) in such decay.

During the Depression, of course, the American Dream had come under considerable pressure. In Evans's photographs we witness not just the flesh but also the fancy of America yielding to the corrosions of time, poverty, and factory— and, more subtly, to the growing conformity of mass culture. Yet I doubt Evans himself really cared about making such points, for the photographs are too rich for simple generalization. His contrast between a heap of junked cars and a delicate horizon line broken by a few naked trees is too austere, too lovely, for sociology.

In this regard, I particularly like the picture of two movie posters plastered on a wall beneath a pair of identical houses, each of which has an oval architectural detail that looks rather like an eye. The posters advertise Anne Shirley, her arms outspread, in Chatterbox, and the wonderful Carole Lombard, looking like a sexy spitfire, in Love Before Breakfast. You could say that Evans's photograph juxtaposes folk and mass culture, but you would not be saying enough. The houses resemble two prim Victorian sisters, rather down on their luck, who are certainly not open-armed chatterboxes. Yet there is also a mysterious rhyme between Carole Lombard's seductive stare and the oval eyes of the twin sisters.

In Evans's photographs we witness America yielding to the corrosions of time, poverty, and factory.

Evans obviously paid careful attention to the sequence of photographs. One image will enhance or surprise the next, until, as in a novel's slow gathering of detail, the mind becomes aware of a richness beyond mere telling. Just when Evans seems interested only in beat-up stuff, there will suddenly be a radiant portrait of a pristinely housed water pump or a view of a town in which the main steet, on a rainy day, looks like a magical river. When we prepare to make a boring statement about poverty and the American Dream, we come upon a picture of a little girl with too experienced a face, standing beside a wall on which is scrawled a carefree drawing of a child.

Evans had a supremely exact sense of form, but he didn't show it off. Just as he seldom imposed an obvious moral, so he rarely called attention to his eye or his technique. He usually shot his pictures straight on, with no funny business about angles, lighting, or crops. As a result, the facts seem to speak for themselves. One has the impression that, for an instant, the world has come into focus and yielded its secret configurations. Critics sometimes use words like "destiny" and "fate" in describing Evans's work. They can use the big old-fashioned words because with Evans the small figure of the artist is not always getting in the way.

Has anyone since Evans successfully put America into a book? Only Robert Frank, perhaps, though his The Americans (1959) is a much lighter work. Frank, too, was interested in ordinary people and pop culture, but they do not seem locked into history or fate. If Evans turned "destiny into awareness," as Frank once said (quoting Malraux), then Frank himself turned destiny into movement. His casual snapshot style beautifully suggested the rattling around, like a ball on the roulette wheel, of America in the fifties. Subsequent photographers have not fared as well. Perhaps it's not their fault. Neither American dreams nor American facts seem especially important when compared with the electronic shimmer of contemporary life.

Richard Avedon's recent In the American West demonstrates just how difficult the task has become. Avedon addresses a great romantic theme, the American West, with a cool contempo. rary eye. He goes out and photographs westerners much as Evans went out and photographed Americans. But the results are vastly different. Avedon brings together fashion and documentary photography, and the result is just fashionable facts. Set against a white backdrop, stripped from their context, blown up to large size, with the negative's black border exposed, these westerners are permitted no power of their own. They showcase trendy angst.

Evans's America possessed a graven stillness, as if the past were weighing the present in anticipation of the future. Frank's was an America as if glimpsed from the window of a Ford. Avedon's America is Avedon. To escape the narrowing charms of narcissism, some photographers choose to portray the homeless—about the only issue that still touches the public heart. Other photographers, more intellectual, take photographs of photographs. It should come as no surprise that Evans himself, among much else in American Photographs, also photographed the homeless, also photographed pictures. He even captured celebrity itself, in his great pictures of peeling posters.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now