Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBIG DADDY

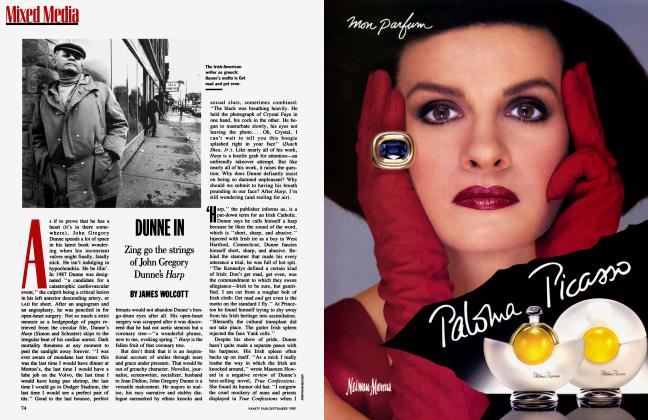

Mixed Media

James Dickey's splendacious new novel, thirty-five years in the "thinking," gives us a lot to gnaw on

JAMES WOLCOTT

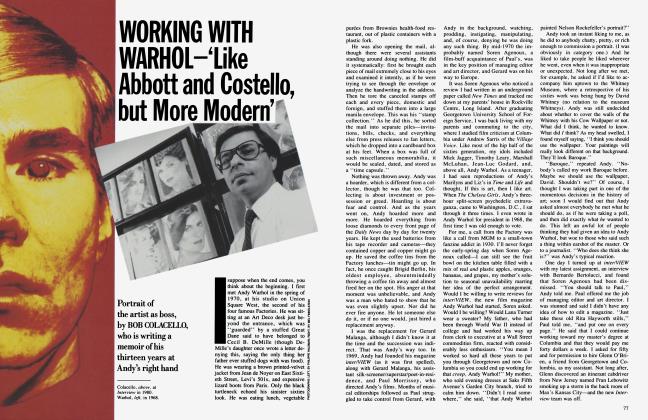

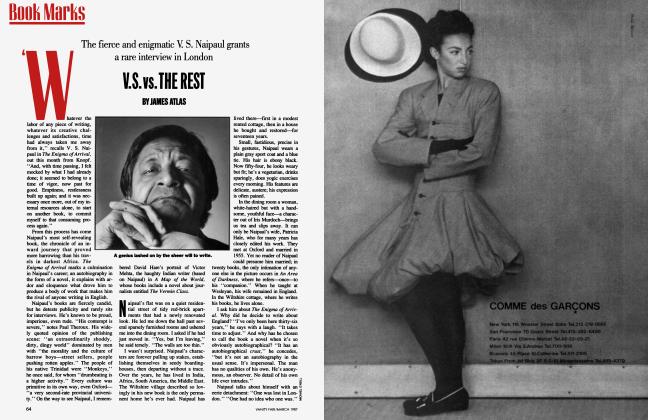

It's a white gospel voice, swung low and heavy on the reverb. Laughter builds from a deep grotto and erupts with a splash. A manmountain of many sides (poet, jock, critic, novelist, teacher, hunter, guitarist, husband, father, Southerner), James Dickey gives off a rumble. He has the basso profundo of a ham actor. One story has him approaching a strange woman at a bar years ago and announcing, "My name is James Dick-ey . . .conjure on that awhile." When he appeared briefly as a sheriff in the movie version of his novel Deliverance, one critic remarked that he leaned on cars real good. A juicier role for him would be Big Daddy in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Like Big Daddy, Dickey has a jumbo presence.

His latest production is Alnilam (accent on the last syllable), a mammoth novel over thirty-five years in the thinking. Yet Dickey is no backwoods Bubba, using his head to butt and uproot stumps. His lit talk is adept, ardent, thorough. He can quote long swoops of Dylan Thomas, entire sections from Dwight Macdonald's movie reviews, brilliant strands of camp from the novels of Ronald Firbank. Big Daddy likes it droll. Hearing that I live a block from W. H. Auden's funky old apartment in the East Village, he remarks, "It was a room from which Ras&o/nikov would have fled." Auden himself Dickey admired, but Auden's constant companion, Chester Kallman, he found worse than "a creep—he was the creep's creep." Is Kallman still alive? I wonder aloud. "Naw," says Dickey, "he's all cruised out." And up that deep laughter booms.

Where Auden built himself a city sarcophagus encrusted with culture and semen, Dickey breathes a woodier air of pastoral. For nearly two decades, Dickey has been a local celebrity along the tree-ringed shore of Lake Katherine in Columbia, South Carolina, where he is writer in residence at the University of S.C. He also conducts classes in poetry

Dad assures her her new dress is pretty, runs from the room exclaiming, "He likes it! He likes it!"

On the desk is a silver-gray mask of Dickey's face that gives him the lidded look of deathly repose. Dickey himself is wearing a noticeable dent in his head, the result of being clunked by the boom of a sailboat. He also had brain surgery last year to deal with a massive subdural hematoma. His mood swings are legendary. His drinking, too. Around him one gets a sense of buried drama, brewing clouds.

To borrow a quip from Bob Hope, Dickey really brings it with him. He's six feet three inches tall, with a big rotunda, and loaded for bear. Just as Big Daddy deplored the powerful odor of mendacity collectin' at his plantation, Dickey punches holes through thin construction. Of James Michener, Dickey says, "I like Michener personally, he's a sincere guy, but there's no fiction on earth as dead as his." He prefers the tutti-frutti roll and cadence of Dylan Thomas, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and Thomas Wolfe, the last a writer "not in very big repute these days with anyone except me and Seymour Krim."

Sprawling all over the place has left Dickey open to attack, and Dickey has often got as good as he's given. A booklength slam by Neal Bowers called James Dickey: The Poet as Pitchman noted on its back cover, "Critics have called him self-indulgent, false, and unconvincing, a drunken and chauvinistic poseur." As Bertie Wooster once said, this sort of remark verges upon the personal. Over the years, Dickey has caught more than his share of political flak. Because he flew more than a hundred missions with the 418th Night Fighter Squadron in the South Pacific during World War II, he was pegged as a maddog militarist. His war record plus his controversial poem "The Firebombing" made Dickey a peacenik target during the Vietnam era. The fiercest load of rock salt came from the poet-guru Robert Bly, who called him "a huge blubbery poet, pulling out Southern language in long strings, like taffy, a toady to the government, supporting all movements toward Empire, a sort of Georgia cracker Kipling." Today the cracker Kipling says amiably that if the government pays farmers not to grow crops, it can afford to pay Robert Bly ("He's sort of a farm bum") not to write poems. Of the protest poetry of the Vietnam era, Dickey says that it didn't last because it was never alive: "It was dead before it hit the page."

two days a week, hauling in armfuls of research books from his personal stash. It's at his home we meet for a long jaw. Guitar cases lean to one side of the sitting room, which is walled with books, including a complete set of Scrutiny. Rain pebbles the cold gray skin of Lake Katherine. A skinny black cat sleeps on a chaise longue. Stirring about is Dickey's second wife, Deborah (a former student of his, whom he married following the death of his first wife, Maxine— she's the star of such poems as "Deborah in Ancient Lingerie"), and their young daughter, Bronwen, who, after

Perched on the edge of the sofa, Dickey elaborates. "You take the Iliad. The Iliad is about an insignificant encounter in Asia Minor thousands of years ago which probably didn't happen and certainly didn't happen anything like Homer said. It's of no consequence historically. But because of the poet's genius the people in it have enormous stature. Tremendous stature. You are involved in their fate. You want to know what happens when Achilles and Hector are finally going to fight it out. That is the stuff of high drama. Immortal. Then you take Dwight Eisenhower's book Crusade in Europe. About a conflict the greatest the planet has ever known, involving millions of men and women, in-

Dickey's mood swings are legendary. His drinking, too. Around him one gets a sense of buried drama, brewing clouds.

volving the history, the future, of the planet. It is completely without stature. It has no Achilles, it has no Hector. But that is only to say Eisenhower is no Homer." It's language that gives life.

And for Dickey it's the "big primary emotions" that ensure staying power. "I'm not subtle," Dickey told a class at the University of South Carolina. But Big Daddy is subtler than he lets show. Perhaps the best reflection of the range of Dickey's shaded moods is his mosaic journal, Sorties, which intersperses workout tips ("The best abdominal exercise is fucking") and self-exoneration ("Who killed Sharon Tate? I didn't") with longer meditations of the mind at stir, the body settling like an old house: "The sadness of middle age is absolutely unfathomable; there is no bottom to it. Everything you do is sad. If you look at

a football game, you are only a middleaged man looking at a football game." Dickey's jottings add up to a selfportrait of a writer who physicalizes everything he feels, believing "the body is the one thing you cannot fake." Leaving, in a period of dilapidation, what? Leaving mastery. "The only raison d'etre for being middle-aged or old is the possession of an absolute mastery of something." Sorties also contains tune-up ideas for Alnilam, whose subject is mastery of air and machine by Blue-Eyed Youth.

Originally called Death's Baby Machine, Alnilam takes its name from the central star in the belt of Orion. It stakes its interest in the dead zone of high altitude, the limitless desert of zero atmosphere, where aviation transcends simple transportation: "It's...it's personal." Its unhero is a blind stick of stubborn resolve named Frank Cahill, who carries sugar cubes in his pocket and injects himself with insulin. Cahill isn't exactly folks. "Someone said, 'Did you get the idea for Frank, who's very forbidding and dictatorial, from Milton's Satan in Paradise LostV No, I said, I got it from Milton." Milton, of course, was blind, and mighty peevish. Essentially a quest novel, Alnilam commences with Dickey's sightless inglorious Milton investigating the crash death of his son, Joel, at flight-cadet school in North Carolina and spirals into supermystification. Occasionally laying parallel strips of prose on the page for an almost split-screen effect, Dickey shows us the outside action—light—and Cahill's inside deciphering of that action—dark—in a single simulcast. It's a tricky optic barrier erected between event and perception. Shifting attention from one strip of text to the other, the reader's eyes ping-pong down the page in a series of ricochets, zigzagging between dark and light, inside and out. A fit reader for Alnilam must be as agile as a skier.

Other obstacles have been rigged on this downhill slalom. Lean and mean on the inside, Frank Cahill is humorless and redneck, barely sympathetic even if blind. His canine sidekick, who savages a pack of rival dogs, is closer to a wolf than to Rin Tin Tin. The pilots and their instructors talk reams of technical lingo. The evocations of night flight have a raw buzz of amphetamine rather than the soothing blue-velvet lyricism of SaintExupery. ("With Saint-Exupery," says Dickey, "you only worry whether he's going to run out of gas or into a mountain.") The basic premise doesn't have the fable grip of Deliverance, and the development of Cahill's son, who emerges as the snot Zarathustra of a cabal of airborne Nietzscheans, is (ahem) a little farfetched. Yet this isn't an opaque mega-book like Joseph McElroy's Women and Men, a 2001-like black slab of inaccessibility that never leaves the ground. As his war record and his poetry attest (not only "The Firebombing" but the famous "Falling," about a stewardess sucked out an emergency door and dropping through "all levels of American breath"), Dickey is at home in the shuddering air, the zodiac of stars. "I want the reader to feel a rapport with the air." He succeeds splendaciously.

The novel also has the advantage of being a prototype. "I can't think of any model for this book," I told Dickey. "I can't either," he replied. Birthing this heavy-metal baby took a long spell. "I got the idea for the book in 1950, which is not to say I worked on it continuously; I wrote twenty-five books in between." The novel slept in the back of Dickey's mind, nudged awake by notes and blueprints for the narrative, down to a minute-by-minute schedule of Cahill's day. "My approach to writing novels is to wait until I've got the plot I want in everything but the final details. Then I sit down to make it happen." He doesn't prostrate himself before the Flaubertian mot juste. "I like to write big scenes."

Alnilam abounds in big scenes. The novel's opening sequence—the blind man feeling his way out of a strange house to take a whiz in the snow—is an amazing piece of empathy. A long session around a bottle of Jack Daniel's becomes an epic swapping of tales, an impromptu course in comparative air war. A bombardier's Plexiglas bubble and a navigator's glass dome become private screening booths for a Major Motion Picture projected on the heavens. The navigator: "You're like a spectator of something awesome and serene; you're not only the only one who's been allowed to see it, but the only one who will ever see it. I had such a view, a view, a three-hundred-and-sixty-degree view of nothingness, just a few inches away from my face." Into the intimate void the night unfurls, and you realize literature has all the time in the world, even if we don't. For variety, Dickey provides briefer jolts. In the novel's sole sex scene, Cahill spanks the skinny tail of

a white-trash gal with a flat object that's foreign to him. Only afterward is he told by the girl that it's his son's slide rule. "You know, the one with all the numbers on it. He put enough numbers on my butt with that thing to build a highway bridge." Conjure on that awhile.

Way back in Sorties, Dickey was casting the novel in Major Motion Picture terms ("George C. Scott could play Frank Cahill, and very well too"), and the final result can certainly be accused of being too movieish. Frank Cahill gets to tell too many people off in scenes that seem to be written for an actor of Scott's angry volume. But there's a crazy wealth to this novel, a wild tumult, and you can feel that there is a whole man behind its dual camera. You don't feel as if you're a snail nibbling on a single scrawny leaf of consciousness. Big Daddy gives you a lot to gnaw on.

When it comes to life and literature, Dickey's a survivalist. You peek around his house—at the photographs of Deborah looking as mysterious and windblown as the French lieutenant's woman, a framed letter from Jimmy Carter (Dickey read a poem honoring Carter at the president's inaugural gala), the stockade of books—and the total effect is of lifelong purpose and fortification. He's mentally dug in for the long haul, his inner shelves stocked. Sex, after all, isn't the only way to get all cruised out. At one point in our conversation Dickey rattled off the roll call of poets in his lifetime who had selfdestructed: Delmore Schwartz, Theodore Roethke, Randall Jarrell, John Berryman, Robert Lowell, Hart Crane, James Agee, Dylan Thomas. Down they all went, on tottering legs. (If he didn't mention Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, it's because he doesn't hold them in much regard: "Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath might be said to belong to the School of Gabby Agony"—Sorties.) Dickey has done more than his share of tottering, but he's managed somehow to keep his sense of calling clean and intact. He hasn't gone whoring after the latest thing. Paraphrasing something he had written earlier, Dickey told me, "Thomas Wolfe may not have been a great writer, but he was a great something." That's how you feel about Dickey after meeting him. And, hell, he could be a great writer, too. Posterity will sort through the baggage. James Dickey may be out of fashion today and tomorrow, but literature has all the time in the world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now