Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA WILDERNESS OF MIRRORS

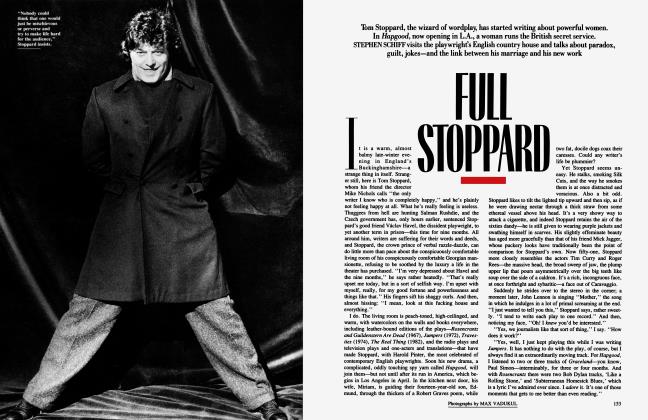

MICHAEL SHNAYERSON

Is Gorbachev's glasnost a ruse? Lenin's was, and that's the question behind Edward Jay Epstein's new nonfiction thriller

Books

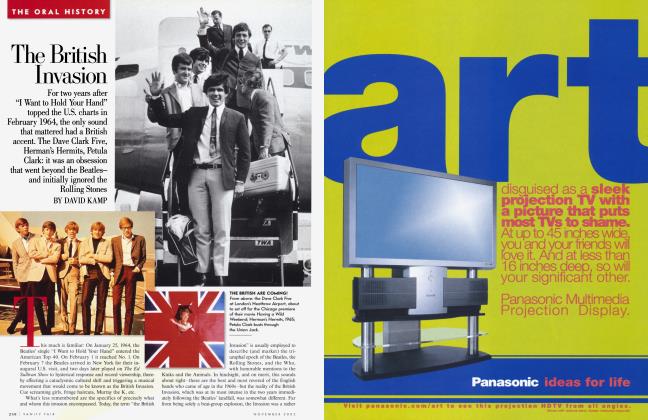

Picture Edward Jay Epstein as an overgrown kid, throwing intellectual darts. Investigative journalist, author of nine books that take on such disparate targets as the Warren Commission and network news, drugs and the diamond industry, Epstein is a prober, a piercer of false truths. "What I like," he says with a hint of mischief, "is disputing received wisdom." His latest book, just out from Simon and Schuster, is deceptively short for a work that consumed a decade of on-again, offagain reporting and research. But that's not the reason for its title. Deception asks the sharply pointed question: What if the C.I.A. has underestimated the K.G.B. for decades and been sweepingly, stunningly duped?

And while we're on the subject, what if glasnost is a ruse?

Epstein bases his case on the worldview of the late James Jesus Angleton, for years the C.I.A.'s head of counterintelligence and indisputably the most eccentric character in the history of the agency. Editor of a poetry journal at Yale, close friend of T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, Angleton rose from membership in the O.S.S. to a postwar position, at age thirty-one, as liaison with Allied intelligence agencies for the newly formed C.I.A. He worked closely and admiringly with his British counterpart, Kim Philby, was devastated by Philby's betrayal, and as a result came to see the world of international intelligence with an almost poetic complexity. In this "wilderness of mirrors," a phrase Angleton borrowed from Eliot, any colleague might be a Philby; any defector might be a fake.

Epstein, researching a book on Lee Harvey Oswald in the mid-seventies, called on a recently retired Angleton to ask his opinion of a defector named Nosenko, who had turned up in the West soon after President Kennedy's assassination claiming to have read the K.G.B.'s file on Oswald and his mysterious months in the Soviet Union. Only later did Epstein learn that the Nosenko case had precipitated Angleton's downfall.

In his first meetings with Epstein, the gaunt superspook spoke cryptically of orchids: how they deceive insects and birds into alighting on their pollen pods by emitting a nectarlike fragrance or even by displaying on their flowers a replica of the underside of a female fly. Brushed by pollen, the carrier flies off to deliver his unintended cargo to the next "deceptive" orchid. Over the years that followed, as one source led to another, Epstein kept returning—a human pollen carrier—and Angleton, over long, brandy-laced lunches, slowly opened up.

Nosenko, he confirmed, had caused a major schism in the C.I.A. that involved not just the question of one defector's integrity but the whole way in which American intelligence viewed its archrival. Almost immediately, the C.I.A. had sensed Nosenko might be a fake, sent over to spread disinformation. But if this was true, it meant that earlier defectors, who corroborated Nosenko's story, must also be fakes. Since the C.I.A. had already bought the "bona fides" of these earlier defectors, and J. Edgar Hoover had proudly passed on to President Johnson tidbits of intelligence they had provided, this conclusion was unacceptable to the intelligence community.

Angleton, at odds with most of his colleagues, chose to nurture another defector, whom he believed Nosenko had been sent to discredit. That defector was Golitsyn; it was from his information that Angleton filled out the contours of the "wilderness of mirrors" that Epstein chose to inherit.

According to Golitsyn, the K.G.B. had undergone a major reorganization in 1959. Instead of merely guarding the home front—protecting state secrets, purging dissidents, and the like—the agency had adopted the more ambitious agenda of manipulating the United States and its allies through a complex campaign of deception. The game involved dispatching numerous "dangles"—agents who feigned disloyalty to their home country. If a dangle succeeded in being accepted as a bona fide defector, he could then more easily pass on disinformation. As insurance, a highly placed "mole" would quietly report back from within Allied ranks on how the disinformation was being received. If the feedback part of the loop was secure, the fake defector could keep amending his story as needed, and the C.I.A. could be directed by its enemy—to assume, say, that production of a new Soviet missile system was lagging when it wasn't.

In fact, the "new" K.G.B. marked a return to Lenin's original vision, an agency that had managed more than once to gull the West. But now there was a further twist, Golitsyn explained. To keep the organization leakproof, only an inner core of trusted K.G.B. agents who rarely left the Soviet Union would be privy to its plans. The "outer" K.G.B. would be fed only low-level secrets or even disinformation, and never would a member of either K.G.B. be allowed to cross that line. The implications were shattering: that none of the diplomats and military attaches whom the C.I.A. had recently managed to "turn" were of any real value, and that the West was working in the dark.

For those in the C.I.A. who had built careers on the enemy agents they had turned, Golitsyn's message—that every new Soviet defector might be embroidering a patchwork of disinformation—. was unacceptable. As for Angleton, he must be paranoid. How, after all, could such subtleties exist when the "eyes and ears" of Western satellites could now "vacuum-clean" information from the Soviet Union? After fierce infighting, a new C.I.A. policy was adopted in the early seventies: defectors would be judged fake or bona fide primarily on the basis of whether their secrets fit in with other known information. Angleton and his Cold Warriors were banished, and Nosenko was declared to have been genuine all along.

Deception reads like a thriller, with Epstein as a real-life detective on the case, making the connections that lead to his amazing speculations about glasnost. But what if Angleton was wrong?

Peter Wright, the former assistant director of British intelligence's M.I.5 division whose best-selling Spycatcher is still under a publishing ban in Great Britain, portrays Angleton as brilliant but misguided and manipulative. He says Angleton's calls for greater secrecy in the C.I.A. were widely viewed as empire building; he implies the counterintelligence chief was wrong to put blind faith in Golitsyn, who may have been telling the truth at first but soon began exaggerating to sustain his importance and make money. Furthermore, he says that by the end Angleton was bitter and paranoid, "consumed by the dark, foreboding role he was committed to playing... a kind of Cassandra preaching doom and decline for the West."

On the computer, Epstein calls up his tailor-made spy program. "Let's say I'm looking for suicides."

William Colby, the C.I.A. director who forced Angleton to retire, corroborates that view in his own book, Honorable Men. "I spent several long sessions doing my best to follow [Angleton's] tortuous theories about the long arm of a powerful and wily KGB at work. ... I confess that I couldn't absorb it, possibly because I did not have the requisite grasp of this labyrinthine subject, possibly because Angleton's explanations were impossible to follow, or possibly because the evidence just didn't add up to his conclusions."

How, one wonders, can a journalist enter the "wilderness of mirrors" and not get lost?

"Actually," says Epstein, "I don't know whether to believe Angleton at all."

At age fifty-three, Epstein lives alone in a spacious Upper East Side penthouse—one of those apartments that journalists and other New Yorkers of modest means invariably scooped up in the early seventies. He has never married, though he often has a girlfriend. This is not to say that he projects the image of a suave playboy in a bachelor pad. Tall but a bit soft in the belly, he comes across more'as a distracted professor, pushing up his glasses and making his points in a silky voice that somehow, incongruously, retains a strong New York accent.

The issue of Angleton's veracity remains haunting. Even now, with Deception about to appear, Epstein takes it up with a brooding earnestness in the confines of his book-lined, green-feltwalled study. "Most people in the C.I.A. feel he was either a fraud or paranoid, and did great damage to the organization." Epstein pauses. "He did do great damage to the C.I.A. as an empire, because he wanted to bring it back to its original mission of gathering reliable information." But Epstein never caught Angleton in a lie—which is more than he can say about many of his other C.I.A. sources. Also, he says, Angleton spoke less to facts than to states of mind.

"If you were discussing Edwin Wilson," says Epstein, "he would start moving the players around like chess pieces. He'd say, 'Well, of course, Qaddafi didn't need to buy C-4 explosives in America. So then why did he use Wilson?' And he'd maneuver around until he came to the answer that Qaddafi wanted to frame the C.I.A. for assassination. When he described to me how the C.I.A. thought about an issue, I tended to believe that. And I think his view was really his own."

Still, Angleton's views were shaped by Golitsyn, and how reliable was he? "Possibly Golitsyn was a liar," admits Epstein. "But Golitsyn is very interesting because he's a museum of Angleton's mind. What I believe happened is that Golitsyn listened to stories Angleton told him and then repeated them to British intelligence, and vice versa.

"Look," he says. "We're used to dealing with stories that have documents and facts, where we can get papers from the S.E.C., where someone like Ivan Boesky can be put on trial. But when you go into this world of intelligence, there are no documents. There's nothing to count. There are .. .memories." Early on, Epstein realized that the few sources of verisimilitude—the autobiographies of spies and defectors—were the least reliable sources of all. "Those books," he says, pointing to several rows of them, "were each written by defectors. But every one of them was written with the C.I.A.'s approval. How do you treat this information from people in the intelligence world who are unable to write honestly about their experiences? The answer I came to is that those books reflect the view that the intelligence agencies were trying to put out about themselves; it was no different from any other form of public relations."

When an agent had served under diplomatic cover, certain facts could be gleaned from public sources: where he had served, his dates of service, and what Epstein calls his "disposition." On the computer screen in his study, Epstein calls up his tailor-made spy program. "Let's say I'm looking for suicides," he suggests. Eerily, names begin to appear: Jack Dunlap, recruited 1957, carbon monoxide poisoning, October 10, 1963. Johannes Grimm, recruited 1964, self-inflicted gunshot wound, October 18, 1968. "Hypothetically," says Epstein, "from that I might be able to conclude there were at least two moles who might have been involved with a certain case at a certain time."

Helpful, too, was any information the C.I.A. had not intended to release. Besides testimony procured under oath in congressional investigations, and scattered documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, there was one relatively new treasure trove: the C.I.A. documents from the American Embassy in Teheran that had survived shredding in 1979 to be painstakingly reconstructed by Iranian rug weavers. Some seventy paperback volumes, titled Documents from the U.S. Espionage Den, lie scattered around Epstein's study like so many Hardy Boys books. (Epstein picked them up for three dollars a copy from a Texas distributor.)

One other source beckoned: the lessons of world history. Epstein scanned the twentieth century and found telling examples of international deception that make Angleton's worldview entirely plausible—so many that after Epstein faithfully recorded them all in an earlier draft, he ruefully decided to cut most of them out for fear of condemning his readers to terminal boredom. Of those that remain, the most chilling are the stories of Soviet deception.

As early as 1921, Epstein observes, Lenin declared a glasnost—the same term was used—with the West, to encourage investment that would shore up the post-revolution economy. Gestures were made: a freer press, a seemingly democratic Soviet constitution, an economic restructuring along capitalist lines. Then a decoy was chosen: twentyfour-year-old Armand Hammer, whose father had been known to Lenin as a founder of an extremist faction of the American Communist Party. Hammer was granted a monopolistic "concession," and soon led other American corporations into the trap. In 1929, having propped up the economy, the first glasnost folded like a carnival tent. Concessions were canceled, investments expropriated, democratic gestures reversed. Over the next decades, four more glasnosts followed, with Armand Hammer often in the lead. Each time, freedoms were promised, then abruptly withdrawn.

As Angleton had pointed out, the Soviet glasnosts were textbook examples from the thin bible of deception, a two-thousand-year-old work called The Art of War, by Sun-tzu. The book's message to state leaders: when weak, feign strength; when strong, feign weakness. "And what is our explanation for this glasnost?" Epstein asks rhetorically. "That the Soviet Union is so weak it has no choice, that the Soviets have basically surrendered."

What no one seems to notice, he adds, is that while the Soviets' consumer economy may be weak, their industrial economy has boomed. "We have this assumption that the Soviet Union is like the U.S., and that if the middle class is collapsing, it will revolt. But the evidence is just the opposite." Instead, the broadcasting of social problems creates a convenient screen, and the pronouncements of perestroika bring foreign investment, as they did in the past. This time, too, glasnost is thawing Western alliances—what need is there for NATO, or for American missile bases across Europe, if the Soviets are no longer a threat?—so that subtly the tectonic plates of world power are beginning to shift.

The West's insurance policy against such dark thoughts is satellite technology. But, as Epstein convincingly argues, the few satellites that scan the Soviet Union produce results no different from those of an old telescope a mile above ground; they simply see the same narrow slice from higher up. More to the point, they have no X-ray capabilities; they see only what lies in plain sight. And because their paths can now be charted by the Soviets, it's easy for the U.S.S.R. to create a false picture—fine-tuned by deliberate infractions of the SALT treaty to double-check U.S. satellite reach—while building new armaments within any four walls. "I don't think there's going to be a nuclear war," says Epstein. "But I also don't think the world is going to be the same in the year 2020 as it is today."

Bold as Deception's premise is, Epstein says barely a handful of people will have read it before it hits the stores: his book editor; a magazine editor or two; his close friend Renata Adler. "And of course," he adds, "my good friend Jimmy Goldsmith."

Every day at lunchtime, alone or not, Epstein strolls down First Avenue to Petaluma, a peach-painted, lateeighties Elaine's with better food. Scarcely has he been seated on this day when a pair of chicly European ladies breeze by with merry greetings. "That's Laure Boulay," Epstein explains when they've passed. "She's the mother of two of Jimmy Goldsmith's children."

Such distinctions are important in discussing the British tycoon, who used to maintain a family on either side of the English Channel, and with whom Epstein enjoys a warm friendship to which he often alludes in his financial columns for Manhattan, inc. Goldsmith has played a major role in Epstein's life ever since the two met in the early eighties through Milton Glaser, who was doing work on L'Express, which Goldsmith then owned. "Eventually I got interested in these takeovers," Epstein says. ''I went to a conference and flew back in his plane. I think we really became friends in 1986, when he invited me on his yacht in Turkey."

Epstein shrugs off the thought that journalists must guard against venerating the rich. "I think the word 'venerate' is wrong," he says. ''Journalists report what's of interest. What's of interest is fantasy. Rich people can act out fantasies." As Epstein sees it, ''people with money are always interesting. Because they can do things arbitrarily. Jimmy could decide to build a great estate in Mexico, and have a thousand workers working there. Next week he could decide to fire everyone and stop all the work. He can do what he likes. People who can do what they like are intrinsically interesting. People who have to do what they do aren't very interesting. I mean, just as a character in a novel, a waiter wouldn't be very interesting.

''But," he adds, "I don't write about Jimmy because he's rich. What I respect in him is his mind. He's a superb bridge player, a world-class backgammon player. He's very likable, a great character; he's one of my closest friends."

Epstein cultivates a host of other friends, so many that his phone rings almost constantly. The calls are from writers, academics, Washington insiders, most of them interlinked. The network traces to Cornell, where Epstein studied under Allan Bloom and wrote a thesis that became his first book, the best-selling Inquest: The Warren Commission and the Establishment of Truth. (The book might have died a commercial death as one of three works in a Viking anthology but for the fierce intercession of Hannah Arendt.) At Harvard, Epstein studied political science under James Q. Wilson and extended his network; this time his thesis became the book News from Nowhere: Television & the News.

He taught briefly—at Harvard, and at U.C.L.A., where he was a full professor—but soon found he preferred journalism, and drifted back to New York, where he joined the staff of The New Yorker. Several books and years later, he has come to include among his friends such diverse elements as the Clay Felker crowd from early New York magazine days, and Washington wheels like Richard Perle, Reagan's assistant secretary of defense for international security policy, and Paul Wolfowitz, slated to be Bush's new undersecretary of defense. ''Also," says Epstein, "I was part of the whole neoconservative crowd for a while. Basically, neoconservatism consisted of Jews who weren't Democrats. Plus Daniel Moynihan and Jeane Kirkpatrick."

The notion of a politically conservative Jewish journalist is oxymoronic to some, but Epstein owns up to the label as willingly as he acknowledges his fascination with the rich. "If a conservative today is defined as someone who believes the Cold War is still going on, I'm a conservative," he says. "On domestic issues—blacks, abortion—I'm very liberal; I would have supported Jesse Jackson if he'd been nominated. But on international issues? I have great respect for the Soviet Union. In other words, it's the respect of one chess player for another. You treat your adversary with great respect, which is to say that you assume he'll always act in his interest, not yours."

Certainly Deception, in its basic assumptions, is an inherently conservative work—so much so that Epstein finds himself to the right of Henry Kissinger, among others.

On the one hand, Kissinger says he sympathized with Angleton. "I thought he was about 75 percent right in his basic attitude," he muses. "I believe, for example, that there's probably an outer and inner K.G.B." Moreover, he finds it conceivable that glasnost is laced with a bit of propaganda. "I have no doubt about their basic strategy," which is to aspire, at least, toward superiority over the West.

"They have written in theoretical journals that if they take away the image of the enemy, NATO will fall apart," Kissinger adds. "They don't say, 'We will stop being an enemy.' So that is a deliberate policy. But to assume they're just doing this to build up until they can put it to us again, I don't believe. Glasnost is not a K.G.B. mirror, it's not a K.G.B. plot. The social problems exist, and they're doing the best that they can with the existing situation."

In other words, Kissinger concludes, "glasnost is a strategy. But it's not a ruse."

"Well," says Epstein, "I don't want to disagree with Henry Kissinger, whom I like and admire. But I certainly look forward to trying to convince him that glasnost is more than a strategy." Undaunted, the darts player toes the line, takes aim again—and lets Deception fly.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now