Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWORDS AND PICTURES

Movies

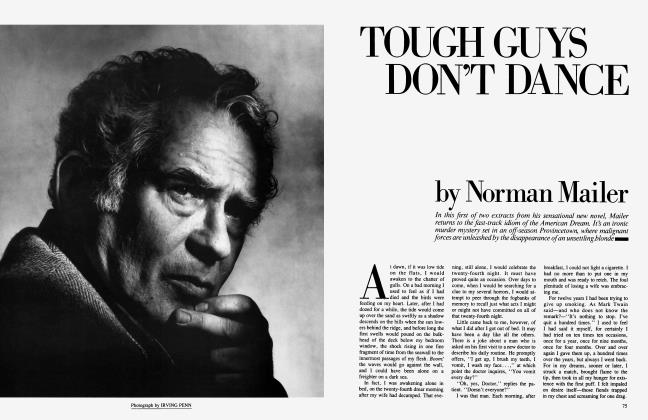

A conversation with NORMAN MAILER about directing the movie of his own novel, Tough Guys Don't Dance

You know, I was struck over and over again while shooting the movie how much it was like being in the army. I was a private most of the time I was in the army, and I kept wondering what it would be like to be a general—my young novelist's brain was working overtime on that. And in a very limited way, directing is like being a small general—a general in an army of sixty people. Everything is determined by the exigencies of the situation. You have only so much money, and you're always making choices with that money.

Menahem Golan [the chairman of Cannon Films] had given me $5 million to make this movie, and he was fairly nervous about it. He would call up the producer—Tom Luddy—and say, "Tom, it's all your fault. You made me give $5 million to a man who's never directed a movie, a crazy man." But there's an odd aesthetic to staying on schedule, because it keeps the morale of the company up. And that's crucial. It's like a good ship; everything works better. That's half your aesthetic: keeping the crew and the actors happy.

V.F.: Some directors use their actors' unhappiness or anger to get a more electric performance out of them.

Well, I'm a great disbeliever in manipulating actors. It's the stupidest thing a director can do. The secret, if there is one, is to go in with a fundamental respect for actors—and it took me twenty years to gain it. I've been in the Actors Studio that long, and I've been married to a couple of actresses, I've got a daughter who's a talented actress and a son who's a talented actor, but it took me forever to understand them.

I used to think actors were asses. I remember during the stage version of The Deer Park the leading man would come back to me every night and he'd say, "Norman, would you tell the goddamn stage manager that the saltshaker was out of place again. It's not supposed to be over there, it's supposed to be over here." And I thought these were the pettiest people I'd ever seen in my life. But you've got to realize that the stage actor becomes a small factory to deliver a product each night. And the product consists of a series of very carefully linked steps—a lot of conditioned reflexes. And for this guy what was involved was he'd reach out his hand for the saltshaker, and as he did he'd start to cry. If he reached for it and he had to divert his hand at the last moment, it hurt the crying.

Acting is the most dangerous art of all. Actors each in their own way, if they are any good, have a force they can tap. And you can't manipulate that force. It's a river. All you can do is direct it. You can encourage it to veer a little to the left or a little to the right. But you must not play with that force.

Before I started, I thought, Will I be able to do it? Will I really know how to direct and know what I've got and what I want? And I discovered that I was really doing something that was natural for me. You know, if film had been going on for the last thousand years, I would say, Well, I've probably been a director in a couple of past lives. It felt right.

But this notion of a director being like a general really works, because sometimes generals know a lot about what they're talking about, and sometimes they don't know much. Either way, they've got to make the decision—everybody must go forward. That's why generals are always slightly in danger of being comic. You know, I don't know a great deal about hairdressing. All of a sudden I was an authority on it. I've been married six times, and through six marriages I've been saying, "Honey, you know, I think I'd like you to wear a little curl over here." And the wife would always say, "Would you get lost?" Now they bring the actress up and they say, "How do you like it, Mr. Mailer?" And I say, "Well, I think it could use a little curl over here." "Yes, sir," they say.

V.F.: So it's a power trip of sorts.

Call it power, I don't know. It's that feeling of people finally listening to you. I think in the twentieth century almost everybody spends a part of their day bearing a certain fundamental relation to power, whatever it is. A dentist—well, he has a few people working for him; he's got to worry about their morale. A guy working in a factory has class relations with management. And they all establish their relation to authority and their rebellion from authority in various proportions. Writers don't. On the contrary, if you're respected in your publishing house, you may see your publisher twice a year, and it's cordial and you have a nice lunch, but that's all. So all sides of yourself don't get used. And writers feel like half-people as a result. Their lives in a way are not as interesting. A movie director is at the opposite end of it—I mean, now you're achieving every aspect of power. But if you can't work with the people under you, you're going to make a total mess of it.

V.F.: It sounds as if your approach has changed since you made your other movies /Wild 90 (1968), Beyond the Law (1968), Maidstone (1971)].

I had a determination in those days that was much more unilinear. I had a way to make a movie, and this was the way to make movies, and there was no other way. All the films that were made up to that point were all wrong. I was going to show the way to the future. I was a prophet—a martyr to my own film. But this time I wanted to see if I could do a mainstream film and see how much I could learn from it—twenty years had to go by to turn my guns around that far. And this time I got obsessed by what I call movie logic.

Menahem Golan would call up the producer and say, "Tom, it's all your fault. You made me give $5 million to a man who's never directed a movie, a crazy man."

Movie logic has nothing to do with practicality or reasonability. It has to do with the fact that you've got all these forces—actors' forces, lighting, production design—and that's a river of forces. And movie logic is: Don't get in the way of the goddamn river. You just move. If there's no reason why a character or something pops up there, don't start to apologize for it. It's just popped up there; the audience will accept it. The one thing you can't do is sever the line of narrative. That is, you have to do a movie that's reasonable enough so when people go home afterward and start arguing about it over the dinner table and say, "Well, why did he do that?'' the reason doesn't have to be in the film, but it has to be ultimately locatable.

I think audiences are faster than moviemakers by now; there is no need to lay it all out for them. I hate films that are needlessly slow. If there's anything I hate, I hate a movie where the guy and the girl are looking off into space, and the guy says, "You know, I think I could fall in love with you." Long silence. Cut to her, she's silent. Cut to him, he's silent. She says, "Well, maybe you will." Cut to him, he's silent. Cut to her, she's silent. Cut back to him and he says, "Maybe." And you cut to her and then you cut to him and then you go out into the twilight. And fuck it! It's unendurable. It's an outrage to twentieth-century sensibility. And it comes from commercials. You know, commercials are always disrupting your sense of timing in order to impinge on your nervous system, so that a commercial will always be guaranteed to be either faster or slower than the show that's interrupted. And a lot of moviemakers are taking that and just using it for hype effects.

V.F.: What you're describing is different from the way things are in novels, isn't it? In novels you have to explain why everything happens.

That's right. I hate books that are too quickly paced. You get a good plot and there is nothing easier in the world than to tighten it up in such a way that you'll have a best-selling novel. And I hate it because I think they end up giving you the shell of the book. And thank you very much, but I don't want to flesh out the characters in my imagination. I want them developed by a writer that's got a sensibility a little more advanced than mine. And so in a novel I love all the excursions.

V.F.: In this movie, you've cast Ryan O'Neal and Isabella Rossellini. They're not big stars, but they're well-known, recognizable names. How important are stars to you in the mix of elements that make up a film?

Well, nothing makes me as miserable as a movie in which there are no stars. Stars are egg in your beer. Then you have two movies to follow: one of them is the movie you're watching, and the other is your knowledge of that star and the parts of your life that are attached to the pictures that star has made. It's like hearing old hit songs.

Look at Isabella. I like Blue Velvet; it's an extraordinary film because it has a true sense of evil. But seeing Isabella in that film or, even more, in my film is extraordinary because there are moments when you're thinking of Ingrid Bergman. I respected how brave she was in Blue Velvet. I just thought, God, that girl's got guts.

V.F.: And Ryan O'Neal? Was he your first choice?

Menahem Golan wanted Warren Beatty. I know Warren slightly, and I know that he does take a while to make up his mind. So I said to him, "Warren, look. You're not going to want to do the film. It's O.K. I won't be hurt. Please, if you're not going to do it, say no right away and don't lose me a year and a half." So he did. And Ryan was my next choice. He and I boxed together years ago, and he's a very good boxer—he could have been a professional boxer. And I got to know his sunny side and his dark side. I thought, I need an actor who's got a lot of things that Ryan has. Ryan's pretty quick-witted, a very intelligent man, which very few people know.

V.F.: Do you have a sense of what your film style is? What is a Norman Mailer movie?

Well, it's hard to talk about your own style. It's a little bit like that famous saying of Ring Lardner's. One of his kids asked him if he was an author, and he said, "Well, you can't say you're an author. It's like saying you're a good third-baseman." If you say you have a style, that implies that you're good. I think I have a temperament that gets into the film. An irony. Good novels and good films have one thing in common, and that's irony. You can't have a good film without it, it's my belief. It's a marvelous English word, irony: on the one hand, it's the spirit of comedy, but it's also the iron laws of necessity. Sometimes I've written something and I've said, "What's wrong with this?" and what's wrong with it is that it is absolutely without irony. Irony gives you an additional point of view. Without it, the gods are not present.

V.F.: You seem to have gotten such a kick out of directing. Will you do more?

Well, if heaven is in a supportive place, then I'll be able to write novels and make films. I'd like to go back and forth. Write a novel, do a movie, write a novel, do a movie. That's the ideal. It would be frustrating to give up that kind of fun.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now