Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

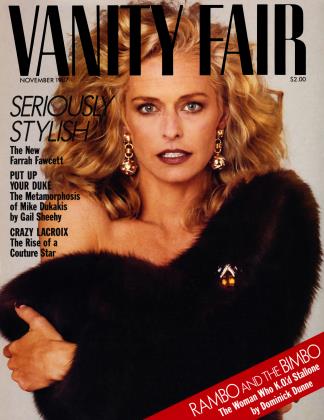

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Metamorphosis of Mike Dukakis

GAIL SHEEHY

Continuing her series of profiles in power, GAIL SHEEHY picks a winner from the Democratic pack. Turned inside out by a devastating political reverse, Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis used it to fuel his self-transformation

Who's the grinning Greek on the platform? The man's mouth is spread so wide his teeth look like a string of taverna lights. Now he leans over to hug someone, his thick black hair flopping over his swarthy forehead, his face flushed with feeling. Then his hands go to his hips, thumbs backward and fingers splayed, the way the men do in dusty Greek villages when the dancing starts. "People ask he tells his audience. Are you kidding? My folks came over on the boat, and I'm running for president!"

"Bravo!" shouts the crowd. They have come from every corner of New Jersey to this restaurant in Edison, American-born Greeks mostly of the first generation, and he touches in them all the chords they share: the reverence for education, the primacy of family, the communal approach to getting things done. Couples with combined incomes of $50,000 drop $500 on the plate for no more than a few spareribs, a drink, and a speech. Young men making minimum wage step up to contribute a hundred dollars in cash. "I feel like I know him," says a teary-eyed teacher, astonished at the welling up of ethnic pride his presence has evoked in her. "He's family."

The governor's speech is good, but his mother's is better. Euterpe Boukis Dukakis steps forward, ramrod-straight at the age of eighty-four, even jaunty in her bright-yellow plaid dress, and she tells the gathering in her flawless Greek, "They are calling me from Greece to claim they are related to him. They are calling me even from Australia." Everyone laughs. Then Euterpe Dukakis draws herself up in majestic, truly Athenian pride, and embraces these five hundred strangers into an extended family with her felt words: "He is not just my son, he is the son of all Greeks everywhere."

All at once a bouzouki throws a lasso of sound into the air. Plaintive and shrill, it pulls the crowd toward the center of the floor. Suddenly there is shouting. Bravo! Bravo! What is happening?

People surge forward. "See, see, he's dancing! With his mother!''

Sure enough, in an uncharacteristic act of spontaneity, Michael Dukakis has come down from his platform to throw his arms over the shoulders of the dancers. He begins moving, slowly, sinuously, in a circle that knows no end. The white handkerchiefs come out and the crowd breaks into rhythmic clapping; a clarinet pierces the ears; people are whistling, shrieking with delight. Euterpe Dukakis, who taught him all that he now, at last, can cherish about being Greek, dances with elegance. Her Michael steps over his clunky wing tips without missing a beat, carefully, properly, executing the oldest line dance from the Peloponnesus. Zorba he isn't, but it doesn't matter—he is down on their level, dancing the old traditional steps, and he is one of them.

Who is this man? And why is he having so much fun? It couldn't be Michael Dukakis, otherwise known as Mr. Clean, whose reputation for integrity over twenty-five years in public life has frozen into caricature. His feet flat as doorstops wedged under a small, trim, wooden frame, he is known by his Massachusetts supporters to stand stiff as a cigar-store Indian. Honest, cool, cerebral, and dull, that's their Mike Dukakis. And cheap. His uncharismatic reputation precedes him on the presidential campaign: look for a soup-and-stew, Neolite-and-Timex type of guy, strictly brown-bag lunches and Holiday Inns and house brands. His emotional-temperature range, they'll tell you, is about that of a climate-controlled museum. No extremes of any kind. Strictly business.

Surely this could not be the same man now standing on the platform, a politician who doesn't talk politics at his audience, but emotes about his mother: "She was the first Greek girl in Haverhill, Massachusetts, to go to college" (waves of applause); brags about big money: "In the first three months of this campaign we raised $4.2 million" (gasps of "Ooh"); and canonizes all of their immigrant parents: "We owe them."

When the music stops, a receiving line is called for, but the crowd is too overcome to stand in line. One by one they press their faces close to Michael Dukakis, and coming off the line they say, one after the other, "He's so warm."

Warm? Michael Dukakis?

Yes! Loosened up, smiling, cracking jokes, dazzled by his own sudden takeoff after Gary Hart's nosedive last May, raking in cash contributions at a record rate, following up his "win" in the Houston debate, among the whole cattle show of Democrats, with a one-on-one debate against Dick Gephardt that broke the two of them out of the pack—why shouldn't this man be warming up? And now he is reading his name in pundits' columns as either the Democratic Party's hottest property or the Republican Party's biggest worry.

The transformation of Michael Dukakis did not begin six months ago, but the adrenaline of a national campaign has accelerated a process that began a decade before. Powdered overnight with the aphrodisiac of power, the hedge-browed, dark-bearded, fiftythree-year-old governor from Brookline, Massachusetts, was designated by Playgirl magazine as one of the ten sexiest men in America. Campaigning, he whips out a pair of dark wraparound shades that look very Onassis or Agnelli, with his bumper sticker running across the bridge (a gift from a local firm), and plays his new image to the hilt, revels in it: "If the news hasn't reached you yet... "

In an election season increasingly focused on what Representative Patricia Schroeder calls "the warm fuzzies" of family life, Dukakis is being projected also as an ideal husband—despite his wife's disclosure of a twenty-six-year diet-pill addiction. Michael and Kitty still live on a sweetly scruffy street of clapboard triple-deckers and small apartment houses. The Dukakis residence, with its twin gables sitting like proper bonnets atop a solid, brick Victorian, shares a wall with another family. Inside, its Danish-modern furnishings have a fond, frumpy, leftover sixties look.

Kitty Dukakis would far prefer a little luxury, but she chooses her battlegrounds. She'll buy Ultrasuede dresses and drag her husband out for celebratory dinners at expensive restaurants, having arranged in advance that he be given the ladies' (unpriced) menu. The difference in their tastes and temperaments has mellowed into a burlesque. "Teasing dispels the tension," says a family friend. To Ira Jackson, the state's former golden-boy tax collector, who used to baby-sit for the Dukakises, the marriage is an inspiration. "He can be stubborn, tenacious, a bull, and he doesn't concede on the basis of any personal relationship. But Kitty's commitments are equally muscular. For two such disparate personalities to find a syntax where they can be totally relaxed with each other, it's unusual."

But, like even the best marriages, it isn't perfect. Although an intelligent, tough-minded woman, Kitty Dukakis seems to have more to prove than Michael Dukakis does. Some of their friends see her as the more ambitious of the two. And when they heard of her public announcement that she had finally put the amphetamine habit behind her five years ago, those who know and love Kitty had to chuckle. "Because, frankly," says one friend, "she's still so wired."

As the transformation of Michael Dukakis into presidential symbol proceeds, to the gleeful Greek, the sexy Greek, and the devoted Greek family man is now added another metamorphosis: from unemotional man to tearful ethnic. Imagine the surprise of all those Boston Irish pols, who believe that the Mediterranean man in Dukakis has been packed in Yankee ice, when they read about their governor in Astoria, Queens, with thousands of Greeks screaming and hollering "Du-ka-kis, Du-ka-kis," and a misty-eyed Michael starting off with "I wish my father could have been here tonight to see this." To first-generation Americans of any origin, not to mention the new class of refugees, Mike Dukakis is the living, breathing restoration of the American Dream.

Cut to another restaurant, nine years before: Dorgan's, in South Boston. A thousand people are jammed into a boardtabled Irish beer joint where a St. Patrick's Day political roast is under way. The Yankee lobbyists are pumping hands with the Irish pols in a profusion of ethnic fraternity, and there isn't a political figure of importance in the whole state who is missing. Except Michael Dukakis, the sitting governor. Never one to hang out with the boys, Dukakis by March 1978 is well into the last year of his first term as Massachusetts's chief executive. It is primary season, but at the moment that seems less important to the pols at Dorgan's than the brand of beer to order; like it or not, Dukakis's re-election seems a foregone conclusion.

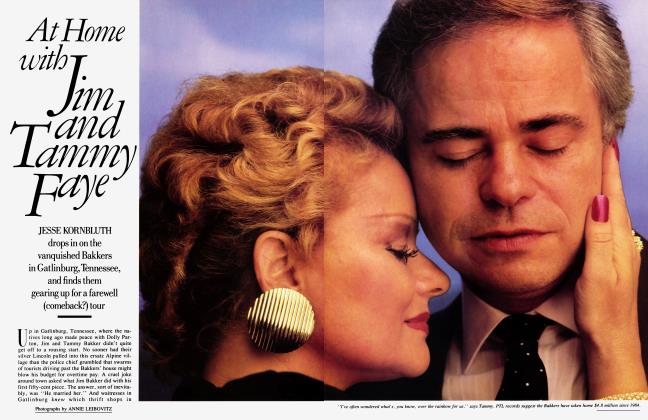

Dukakis faced his mother with the facts: she's divorced, she's Jewish, and she has a child.

Tommy McGee, a bantam rooster of a man who is then speaker of the House, stands up to throw his wisecracks on the fire. But something different comes out: "On the drive over here, when I thought of the possibility Michael Dukakis might be elected to a second term, I threw up in the back of my limousine.''

Slack-jawed, people sit in silence while from the speaker pours wave after wave of angry, bitter slurs about the governor he is currently serving. The mood of frivolity shrivels. By the time McGee winds up, people are almost literally picking up their feet to avoid stepping in the vitriol.

"You all know what you should do on that vote," he glowers, and sits down.

Despite McGee's reputation as a ruthless insider, his words were not discounted, according to a participant. Such uncontainable venom illustrated the disastrous state of relations Dukakis had allowed to develop with his legislature. People were calling Dukakis names behind his back: cold, arrogant, heartless. To all this unrest, the governor turned a deaf ear, so sure of himself he seemed sealed behind glass. Dukakis's single goal, at least as far back as college, was to be a governor. "A political wunderkind," says longtime friend Don Lipsitt. When he attained that goal in 1974, Dukakis bragged about leaving politics at the statehouse door so he could get on with the business of Good Government. He became such an insufferable know-it-all, according to movers and shakers in Boston who attempted from time to time to offer an opposing view, he would start his patronizing spiel with "Let me explain it to you one more time."

Blinded by his own stiff-necked selfrighteousness, Mike Dukakis slammed into that 1978 primary election like a bird hitting a glass wall in full sunlight. The vote was heavily against him, and, worse, the rejection was pointedly personal. It was, for Michael Dukakis, the first failure in forty-four years. And unequivocally the lowest point of his life.

How did he get from there to here over the last decade? For a wunderkind like Dukakis, often the best thing that can happen is a major mid-life crisis. That appears to be what happened as he began his passage into mid-life with a major defeat and a series of heartbreaking personal losses.

John Dukakis, son of Kitty Dukakis from a former marriage, made a routine call to his folks' hotel room the night of the 1978 primary, expecting to hear whoops of victory. "When they realized it was me, a sudden hush came over the room," he recalls. "It was very much like being told a close relative had died."

An old college friend called the next morning. "Very tough," Mike Dukakis told him. "It hurts."

John caught the first plane to Boston. "I found my dad in his rocking chair looking out the window of his office. It was awful. Clearly, most of what was going on was internalized for him." Only when the family retreated to Nantucket for a week to lick its wounds did John Dukakis realize that his normally imperturbable father was not sleeping. Dark divots appeared under his eyes. Whenever John went into his parents' bedroom, Dukakis would be lying, mummy like, face up on the bed.

The phone never rang. Michael Dukakis began to mutter questions. Humble questions. "What did I do wrong?" questions. Kitty, always the carrier of the more flamboyant emotions for both of them, railed at the opposition for using anti-Semitism against her to bring Mike Dukakis down. She is the daughter of a talented Boston Jewish family. ''That had nothing to do with it," Michael said flatly.

He began using the phrase ''I blew it." He said it over and over again. Then he began to telephone the many people he'd brought into government and to hand write notes of apology. Always he used the same, blunt phrase: ''I blew it."

Having lost in a primary, he was stuck in limbo for the next three months, a humiliated, personally rejected lame-duck governor.

Putting one foot in front of the other, he turned up a week after his defeat for the kickoff of a progressive-referendum campaign. No one expected him to honor this prior commitment, least of all John Sasso, the fiery organizer who later managed Geraldine Ferraro's campaign for vice president. South Station was swarming with two hundred liberals, most of whom had sat on their hands during the primary, as liberals are often wont to do, never expecting their governor's defeat but determined to send him a message. All at once a ghostly figure appeared. It was Mike Dukakis, drained, but composed. He gave a little talk about the bright future for homeowners' reform.

Always he used the same blunt phrase: "I blew it"

People came up to him and mumbled their guilty catechism: ''It's such a shock," ''My God, what just happened?" and "Gee, we're really sorry."

Brookline's liberal idealists had always cleaved to Dukakis for being above politics. So he had practiced what they all preached: he'd come into office and sealed all the cookie jars in which the hands of state-government officials had historically been caught. And this is how they rewarded him?

If Dukakis harbored any bitterness, it never showed.

That left an indelible impression on Sasso, who two years later began plotting the governor's comeback with Dukakis (and is now his campaign manager). "He's a person of great strength, and the way he handled that defeat showed it," says Sasso.

"But he still wasn't quite getting it," says his son, John. "It took him a very long time, I'd say about six months, to really get under control."

One of his very few close friends, Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, a neurosurgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital, has called the defeat "the single most influential thing that ever happened" to Dukakis. "He blamed it totally on himself. It took him quite a while to get through the tremendous pain and humiliation and guilt; he felt he'd let people down."

Don Lipsitt, a psychoanalyst who has known the Dukakis family for twentyfive years, observes, "I don't think Mike was ever clinically depressed." Part of that impression, he believes, has been created by Kitty's often quoted characterization of the defeat as "a public death." But a person in the depths of depression would withdraw, slow down, and not be very motivated to do productive work. "I think," says Lipsitt, "he began to examine himself in exquisite detail, in a very cognitive, intellectual way."

At first, it was virtually impossible for Dukakis to believe that his high principles could have been knocked down. "We did some real talking in those months," says Kitty, who is credited by both Michael and his mother as a tower of strength during that period. "It hurt to see him hurt. But he became more comfortable as time went on with inviting people to come in and talk."

His closest Greek friend since Harvard Law School, mild-mannered Paul Brountas, says, "He looked at the mistakes he had made—and Lord knows there were plenty of us telling him about the failure to listen, the inability to be persuaded by others, and the unwillingness to admit he might not be right on absolutely everything. He also looked at his relationships with people. And he said, 'My God, I should have spent more time with the speaker, with the president of the Senate. I fought very hard for my programs, but I wouldn't let them have theirs.' "

The Duke, as many call this cool man, addressed the rational grievances of the voters first. His undistinguished challenger, Ed King, was carried into office on the winds of property-tax reform. Why hadn't Dukakis seen the tax revolt sweeping the country? "Tunnel vision" was one of the criticisms he hadn't stopped to hear.

Now the wunderkind, who had always been in such a hurry to be ahead of everyone else, had the enforced luxury of the next three years to examine the personal charges against him: that he was stubborn, holier-than-thou, and a cold, unemotional, insensitive man.

Stubbornness. This, above all, registers as the most consistent mark of Michael Dukakis's character. Monos mou—"by myself''—if not his first words, he admits, were certainly the watchword of the second son bom to Panos and Euterpe Dukakis. Was he always stubborn? I ask his mother. "Always. Michael never gave up."

The dirty-socks wars would turn into marathon tests of will. "Those socks won't do," his mother would say. Michael would insist his choice was right. "Then go to your room and close your door," his mother would order, "and don't come out until you're ready to do what your mother tells you to do." An hour or two would pass. "He never gave up," shrugs Mrs. Dukakis.

She, too, was a formidably strong figure, however, and determined to "channel" his stubbornness into perseverance plus obedience. Euterpe Dukakis, who became the first GreekAmerican teacher in her town, was turned down for her first teaching job because she was of foreign birth and had an accent. The sting of rejection is still fresh. Even today, her speech is so correct it borders on the stilted, and her posture is almost a parody of prideful erectness. She has never relaxed her vigilance in polishing her son's selfpresentation, so that he would pass as a full American. Whenever the boy mispronounced a word, Euterpe Dukakis would correct him. Later, she would find Michael standing by himself in front of a mirror, mouthing the word over and over until he got it right.

Did young Michael ever have a failure? I ask his mother. Her smooth forehead braids in thought; no, he didn't bring his disappointments home. Finally she remembers one occasion. His sixthgrade teacher kept scolding him for writing too small. Michael stubbornly persisted. The teacher gave him a C —the only C he ever got, and still it remains engraved on the memory of his octogenarian mother.

Then, and only then, castigated on all sides, did Michael Dukakis listen and amend his ways, a pattern that would repeat itself until it was expressed years later in the definitive failure of his life.

His father's example also made a significant imprint. When Panos Dukakis came to America from Turkey in 1912, alone, at the age of fifteen, it was with a burning desire to get an education. Panos earned entry to Harvard Medical School eight years later—by himself. A stem disciplinarian with his two sons, Dr. Dukakis had two passions in life, work and family. The family had no social circle to speak of, since the Greek community was gathered in Boston, where its activities emanated from the church. They settled in Brookline, a "just so" suburb a few bus stops from Boston. Its exclusive club is listed under "T" in the phone book (for The Country Club). The few Greeks were scattered among an affluent Jewish population, and the ethnic Irish were mostly public-service employees. Michael connected with both groups, working summers collecting garbage with workingclass Irish kids and competing at Brookline High for grades and girls with rabbinically bright Jewish boys.

"Brahmin Boston just wasn't part of my life," Dukakis told me, a touch of reverse snobbery showing. "You know, big deal."

Despite his father's increasing affluence, the family paid cash for their first house and never traded up, never bought a thing on credit, never changed their living habits to keep up with the Joneses. Michael, the younger of the two sons, was designated to become a doctor. Both parents impressed upon him the responsibility to give back by serving one's fellow citizens. Dr. Dukakis exemplified those values by delivering hundreds of babies to Greek families for little or nothing. According to a Brookline friend, Dolores Mitchell, "he wasn't the sort of father a sensitive young man would want to disappoint."

Too good was another of the subjective beefs that even his best friends had with Michael Dukakis. "Michael had everything you'd hate in someone your age," says an admiring high-school classmate, Haskell Kassler, who, like Brountas, went on to become a prosperous Boston attorney. "He was an exceptional student, varsity in all his sports, played first trumpet, and on top of all that he dated one of the most popular girls in school." There is still controversy over whether or not Michael won the girl, Sandy Cohen, but his competition, Bob Wool, did definitively whip him for election to seniorclass president. Michael shunned the school's invitational boys' clubs, disapproving of their blackball powers. And that, according to "Hasky'' Kassler, probably cost Michael the presidency of his class.

"Your mother doesn't remember you ever talking about any disappointments or losses," I observed in my first interview with Mike Dukakis.

"There weren't many," he came back, cockily. Defeats or mistakes weren't admitted in the Dukakis household—no, he just kept putting one foot in front of the other until he had made up for his loss by winning the presidency of the student council.

"What about when you first realized you wouldn't grow up to be a giant?" I asked.

"I had myself programmed to grow three inches every year until I got up to five eleven," he told me. "I was on time until I hit about five seven. Then I started slowing down."

That was in junior high. But when a gym teacher directed, "All the tall kids line up over here for basketball," Dukakis blindly ignored his limitations and joined the tall kids.

This extraordinarily driven boy once sighed to his mother, "Life is just hurry time—in some ways I wish time could stand still."

In college he continued to improve on his Mr. Clean credentials. Swarthmore, a Quaker school in Pennsylvania that was strong on community involvement and internationalism, opened up new worlds. "He was a bit daunting in his ability to carry on multiple activities," recalls his roommate of three years, Frank Sieverts, now spokesman for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, "and still manage to hand write all his papers." Dukakis was the kind of kid other people's mothers loved to hold up as an example. Always a plugger, he made seventh man on the junior-varsity basketball team, second-string catcher on the baseball team, and he ran cross-country. That was one of the attractions of his small college: "I wasn't a star, but at least I could play," he says candidly.

Dukakis wouldn't join any of Swarthmore's fraternities, refused initiation into the secret society patterned on Yale's Skull and Bones, and started a civil-rights effort on behalf of black students who were being refused haircuts in town. Putting to use a skill he'd learned in camp, he developed a brisk barbering business, and while his victims were pinned under the sheet, he proselytized for his political ideas.

There was Mike Dukakis, already in full flower: no bleeding heart, he dealt with injustice by direct action, providing compassion on the cheap.

No amount of tenacity, however, could get him through physics. He had to call home and admit he couldn't live up to his father's expectations that he would become a doctor. But young Dukakis had another goal in mind.

"Already by our freshman year, when we'd shoot the breeze about our futures, he had a lot of people talking politics," remembers Sieverts. "But all of us would think rather vaguely in terms of becoming senator or representative. Michael was the only one I ever knew who said, 'No, I think governor is the way to go. State government is the place you can really make a difference.' " By the time he was nearing the end of law school, his goals had become even more defined, even messianic. "As a governor, you're kind of running a small country," he told Brountas. "You have a lot more power than even a senator."

Between college and law school, he waived the easy college deferment taken by most of his friends, and despite his father's objections went to Korea as a draftee. "I wasn't thrilled about sitting in a rice paddy for sixteen months," he admits, but he kept his mind occupied by learning a smattering of Korean and traveling. Returning in 1957, Dukakis gritted his teeth and did his time at Harvard Law School, winning a local office at the same time. Burning to get to work in public service after graduation with high honors, he went into a law firm that would allow him to launch his political career.

Never one afraid to be different, Michael Dukakis found the right bride monos mou—by himself. Straightforwardly, he faced his mother with the facts: she's divorced, she's Jewish, and she has a child. He had known all that before he ever allowed his old girlfriend, Sandy Cohen, to fix him up on a blind date with Kitty Dickson.

Their first date bore the makings of a disaster. Kitty had always suffered from a stare-at-her-shoes shyness. Her father, Harry Ellis Dickson, a natural musical artist who played first violin with the Boston Symphony and later became associate conductor of the Boston Pops, used to scold her for being so shy. As a child she played the piano, badly, gave up, tried acting, shriveled with stage fright. Not until she was eleven or twelve did she discover modem dance as a mode of self-expression. Even then, Kitty knew her limitations would not allow her to be a performer, and settled on teaching interpretive dance.

By the time she reluctantly agreed to the date with Michael Dukakis, Kitty felt like an old woman. Twenty-six. College dropout. One failed marriage. Several miscarriages. A three-year-old son. And a rotten body image. Swell, and here, up the walk of her low-rent apartment, was coming "that brilliant Greek kid from the more affluent side of town."

As the couple prepared to leave to see a movie, Kitty's son, John, started howling hysterically. She steeled herself and got outside to the street. With the special castigatory powers of a three-year-old, the boy pressed his nose against the glass and followed his mother from window to window. After that, Michael insisted they take the toddler with them on dates. "The most attractive thing about Michael was the gentle way he handled John," says Kitty. John, today twenty-nine, can't remember when he accepted Michael Dukakis as his father. It happened effortlessly; before he could reach the top buttons on elevators, he remembers, he was proudly campaigning for his adoptive father.

The newly married reformer had no trouble winning re-election to the state legislature for an eight-year stretch. There he made his initial splash by sponsoring the nation's first no-faultinsurance law. So clear about himself, so utterly unaware that others might be wrestling with hidden demons, he moved like a bullet train through the next fifteen years with a tunnel vision so complete it came as a total shock to discover, in the midst of the most important campaign of his life, that all along, unable to reach him, his wife had been an amphetamine addict.

In 1974 he found a bottle of her "diet pills." Kitty had always been thin. She took her interpretive dancing seriously and routinely performed in leotards. To the rational Dukakis, diet pills simply didn't make sense.

"I felt caught," admits Kitty. "Michael early on was just not a good listener. I'd gotten very frustrated." She later took up her own causes (Holocaust studies, refugees, environmental beautification), "but in the sixties and even the early seventies," Kitty reminds us, "I don't think women expected credit."

The couple discussed the physiological problem, and Kitty promised to go to their family doctor and break her habit. "In three or four months she was off them," says Michael, "or I kind of assumed she was." In fact, feeling depressed as she tapered off, Kitty resumed taking varieties of Dexedrine. Five milligrams every day gave her a kick, she has said, and everything she did well she attributed to those magic white pills.

When I asked how the body's natural tolerance of such a tiny dose would still allow her to feel a kick after all that time, Kitty Dukakis said, "There might have been times when I took more than one pill, but they were very few." The natural volatility of her temperament became more pronounced. And over the constant drain to her already watereddown confidence she developed a loud, aggressive surface.

Michael turned back to his first campaign for governor and just kept putting one foot in front of the other. The opposition laughed him off, as usual underestimating him. He won.

The elixir of victory evaporated quickly. Although he had campaigned against the profligate ways of the previous administration, the new governor had no concept of the grave depths of the state's deficit. One bitter day in February 1975, the secretary of finance Dukakis had brought in with him broke the news to the governor and his staff.

"We're three-quarters of a billion dollars in debt," a staffer remembers John Buckley saying. "The state's bonds are going to be re-rated downward. We'll have to borrow to pay off the debts." In fact, Massachusetts was tottering on the brink of default.

"No one breathed a word," recalls Dolores Mitchell, then coordinator of the Cabinet. "We were too stunned." With a constitutional amendment requiring the governor to balance the budget, Dukakis faced either fiscal disaster or probable political suicide. He froze.

Over the next eight months of his term, bills literally piled up in shoe boxes. Governor Dukakis, a man who had never bought so much as a car on credit, drilled from childhood to pay as he went, would not, could not, comprehend the catastrophe waiting to happen.

Kane economia—economize, his father's motto— eventually became the emblem of the values Dukakis imposed on state government from top to bottom.

He didn't need perks, why should others? His own needs had been pared down long ago to a minimalist art.

When Dukakis walked into his $40,000-a-year job as governor, his income h^d never exceeded $25,000. It was in that first term that he earned his reputation as a skinflint.

He cut $300 million in human services. His liberal supporters were aghast: how could a progressive Democrat be so utterly soulless? It was the cool, aloof, accountant-like manner in which he delivered them, as much as the cuts themselves, that really turned his core constituency against Dukakis. At the same time, he antagonized the techies who had been laying the very roadbed—Route 128, Boston's answer to Silicon Valley—for the economic turnaround in Massachusetts. "There's no question he was perceived as a major impediment to business during his first term," says Mort Zuckerman, a major Boston real-estate developer, now owner of U.S. News & World Report.

But the real blind spot for Dukakis lay in operating as a politician too principled to practice politics. No one could talk to him about an appointment for a friend, regardless of how qualified. His lieutenant governor was Tommy O'Neill, son of the congenitally charming Irish politician Tip O'Neill. "I was the battering ram for everyone else," says O'Neill. "Kitty and I."

"Brahmin Boston just wasn't part of my life. You know, big deal "

Continued on page 182

Continued from page 127

Kevin Harrington, the towering Irishman who presided over the Senate during Dukakis's first term, swears that Kitty entered into a thousand conspiracies with him to get things done politically that Michael was too "good" to do. Harrington describes her marching into his chamber, during session, and striding up to the president's rostrum to whisper in his ear.

"Why can't you get this vote through?" she demanded, according to Harrington. "Michael really needs this program. "

"We can't get the vote through, Kitty, because your husband is alienating a third of my Senate."

Kitty maintains that she rarely entered the Senate chamber and doesn't remember any "conspiracies." But according to Peter Pond, an advocate for Cambodian refugees who has often been on the barricades with Kitty Dukakis, "she goes to the top and says 'Do it.' And she often pulls off something spectacular. Of course, she has also gotten people angry, because she has no patience with bureaucracy."

The charge that Dukakis is henpecked, launched in the nastily personal Ed King campaign, still clings among some of the colorfully chauvinistic characters who inhabit the Massachusetts statehouse. But those closest to the Dukakis family assert that Michael Dukakis wears a full set of pants. His much-touted involvement in domestic chores is a matter of choice, predates feminism, and in fact reflects his traditional Greek reverence for family. It was very much his idea to walk his two daughters to school every morning before hopping the subway to the statehouse. And it was he who would look at the schedule and bark, "I will not go out four nights this week—I want to see my kids!" Heartfelt encomiums come from women who worked for Governor Dukakis. His model allowed them, too, to meet obligations to their families.

"You have to make choices in public life between best friends and a family that is close to you," says his son, John. But family closeness could not salve all the wounds of that post-defeat reflection period. One loss seemed to follow another. The death of Michael's mentor, Allan Sidd, had been a blow. And the year following his defeat saw the death of his father. The day of that funeral was a bitterly sad one.

No one came. Well, not no one, but the usual full court of legislators and old appointees that a politician can count on at such times was noticeably thin. "It must have been devastating for him," says a co-worker who attended the funeral. But Michael Dukakis drew his pain deep inside and expressed not a word of mourning to his friends.

The Duke had already started to teach at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government. He was not looking forward to an involuntary mid-life career change that, for all he knew, might be permanent. "But Dad was up within the first week," reports his son. "I could hear the excitement in his voice." Kitty, too, picked up on work toward her master's degree, having graduated from Lesley College. Michael studied hard to prepare himself, as he always does. And very soon he became good at teaching, drawing openly on his own mistakes to supplement the case-study method. His challenging but adoring students served as the ex-governor's group therapy.

Cold, unemotional, insensitive. This, above all, was the perceived personality trait that seemed to be getting in Dukakis's way. Kitty told him so.

He has always kept his distance from emotional politics—demonstrations, protests, passionate campaigns for allbut-lost causes. Although he credits John F. Kennedy with being his inspiration to enter politics, he never worked in his campaign, nor for Bobby Kennedy or Eugene McCarthy. When Martin Luther King came to Boston to march in 1965, Dukakis wasn't among the marchers. He never took part in anti-war protests during the Vietnam years. And when I asked how he had participated in the busing crisis that almost tore Boston apart ten years ago, he couldn't remember.

According to those closest to the Duke, he is not without emotional range. He can blow up at the kids and Kitty. He gets choked up over tragedies that befall friends. When it comes to conflicts between pursuing his own goals and dropping everything to close ranks with family at inconvenient moments of crisis or ceremony, family comes first. But you'll never hear him talk about his wounds. And as Evelyn Murphy, his lieutenant governor, says, "you'll never see where Michael hurts."

"I'm not a neutral guy, and I never was," Dukakis insists. "I always loved what I was doing."

For the man who, like Dukakis, starts out "running for president," or playing to win rather than playing not to lose, the dividing line between work and private life is blurred early. He works even at play. Seldom introspective, the wunderkind rarely shares his private thoughts, fears, and hurts. They are locked up because he is afraid to admit he is not allknowing. Somewhere, back in the deep recesses of boyhood, each wunderkind I have studied recalled a figure who made him feel helpless or insecure. It may have been an overbearing mother or a father who withheld his blessing, or a parent who meant to be of goodwill but locked in the chosen offspring to fulfill a family destiny—"You have the chance I never had to become a doctor," and, as in the Dukakis case, "You must enhance the family name by reaching the highest levels of public service."

The most important legacy of such a dictate is the last and implied part:. . .or you'll be nothing. All the wunderkinder had a mid-life crisis—a screeching inner halt that forced them to take stock. Jimmy Carter, for example, after being defeated in his first race for governor, went into a profound period of despair and penance, seeking rebirth through religious commitment. Once his mental balance was restored, and the defeat assimilated, he went on to run again and win.

To me, the real question is, did a transformation of character take place in Mike Dukakis at a deep inner level during those exile years? Or did he do a rational makeover of his political style in order to appear more open and accessible?

He did go about building bridges to those he had offended, one by one. Over Labor Day weekend in 1980, for example, he followed State Representative Philip Johnston around, to see the improvements Johnston had made in the former governor's failed workfare program. "He was trying to tell me in his own way, 'Look, I know I didn't listen enough.' I appreciated on a personal level that he was reaching out to me. I didn't think it was phony, either.''

Mitch Kapor, the whiz kid in the Hawaiian shirt who founded Lotus, the world's largest developer of personalcomputer software, is one of the many entrepreneurs spawned by M.I.T. and Harvard who have helped create what Dukakis calls "the Massachusetts miracle.'' Kapor says it would be simpleminded and wrong to give the governor credit for the boom. "But he's grown to appreciate the absolute importance of high tech to Massachusetts. He's been able to see the big picture.''

Traveling in his state, one hears the governor praised repeatedly for innovative public-private partnerships and for spreading the new wealth around to formerly depressed areas. The already impressive figures keep improving. Unemployment had dropped, as of August, to 2.5 percent—the lowest of any industrial state in America. Dukakis has cut taxes five times in four years. More than 30,000 families have been taken off welfare and provided with the training, day care, and transportation to keep jobs which make them taxpayers.

Mort Zuckerman sees Dukakis as having grown into a skilled orchestrator of government and business. Even his most garrulous detractor, Kevin Harrington, admits with grudging respect that "the man has done a 180-degree turnaround." One still hears grousing around the statehouse, though, when leaders are asked if Dukakis would make a good president. "A good president, maybe," says one. "A good buddy, no."

His close friend Paul Brountas hasn't seen much change: "The Michael Dukakis of the first administration is not substantially different from the Michael Dukakis of today."

This is a short man from a small state who is easy to underestimate. But mark this well about Mike Dukakis: he will always overcompensate. Despite the fact that his immigrant Greek family provided an airtight upper-middle-class home from the time he was born, that he took political root in an affluent suburb, was polished at Harvard Law School, and can speak six languages, there isn't a trace of Haaahvad snootiness about Michael Dukakis. He consciously avoids dropping his r's in Des Moines. Plunging into steak houses and Greek pizza parlors across Iowa, he is the swarthy ethnic in rolled-up blue shirtsleeves who talks straight to the voters. They don't have to be Greek to appreciate his unpretentiousness. A retired farmer who took Dukakis around southern Iowa says the rural Iowans were impressed that he talked to them for fortyfive minutes before his speech, and he listened. "Mike is one of us. He isn't the kind of guy who'd have fourteen forks at his dinner table."

Racing through an airport, he is still rarely recognized and scarcely even seen. But one can always tell where he is, because there's a ripple in the crowd and a hole in its center. And that is where, five feet eight without his thick Neolites, one can always find Mike Dukakis—putting one foot in front of the other. But that plays well with short people. "He'd be the first president to be shorter than me," says a Tampa man approvingly.

He does discreetly compensate for his height by having a riser slipped behind his podium, but size is not a problem on the tube. And with four years as a moderator of public television's The Advocates under his belt, he has learned how to speak in sound bites. What is more unusual for a politician, he genuinely seems to like the press. After interviewing the governor twice for this article, I still had some personal questions to ask. Pat O'Brien, his highly independent press secretary, approached his van on my behalf. "Sure, c'mon, Gail, jump in," he called jauntily. "I could get used to this," he told me, settling back on a cushion embroidered with the presidential seal. "I can see a whole fleet, Van Force One, Train Force One..."

Cautiously, I broach the awkward subject of his brother. "No brothers were ever closer," he says of Stelian Dukakis. "He was my leader." Three years Michael's senior, Stelian had entered Bates College and was itching to get into politics himself. "And suddenly, bang, for no apparent reason..." Dukakis's voice trails off.

His brother had a mental breakdown. Thereafter, although he had lucid periods, Stelian never fully regained stability. Some of Stelian's more embarrassing escapades took place while Michael was a Brookline representative. Paranoid, the disturbed man would collect his brother's campaign fliers off the town's stoops and substitute his own, illconceived literature. People would talk. "Isn't it a shame?" "It must be terribly upsetting when you're running for office, having a brother who's, well..."

Michael Dukakis swivels to face me, eyeball-to-eyeball, the way he must have with his brother's detractors then. "You've got to be supportive and as understanding as you know how. I can't tell you what great shape he was in, the best two-miler in the state," and the recollections pour forth, putting his brother in only the best light.

"Mike never did try to distance himself from Stelian," Dr. Lipsitt had told me. "He dealt with it the way I've seen him deal with other disappointments. He showed extraordinary tolerance and never said anything negative. For a man so politically ambitious, that was very impressive."

Further heartbreak came when Stelian was knocked off his bicycle by a hitand-run driver. He was hospitalized and remained comatose for four months. Michael, then thirty-nine and running for governor, kept a daily vigil at his bedside, "hoping he would move a hand, or respond at all. It was a terrible experience for my parents, for me, for all of us."

When Euterpe Dukakis told me about that tragedy, she indicated that a decision had had to be made about whether or not to keep her son alive on support systems. Michael Dukakis says now, simply, "We lost him."

I ask if he disciplines himself not to show the things that hurt. "Not consciously," he replies slowly. "I've never been terribly introspective."

Is he consciously trying to let go and show his emotions a little more these days, to offset the image of coolness?

"I think I've gotten more relaxed these days," he says. "The defeat did a lot of that for me. It made me more philosophical." He smiles, and mocks his tendency to self-righteousness. "I'm less sure today that I have the revealed truth."

So what do you think about Dukakis? people inevitably ask. Running on character is Mike Dukakis's best issue, and he knows it. His blunt phrases—"I believe we can make a real difference in real people's lives"—come across as sincere. With a sitting president believed by 60 percent of the American people to be a liar, the prospect of being led by a man who seems congenitally incapable of lying is most refreshing. On character, I would have to give Michael Dukakis high honors. His stubbornness, however, is a trait to be weighed from both sides. Channeled into the perseverance needed to run a long hard campaign, it is both admirable and formidable. But a stubborn, self-righteous president, dug in against Congress, evokes the prospect of an irresistible force meeting an immovable object. The example of Ronald Reagan's Iran-contra policy and intransigence on the budget is instructive.

Dukakis often sounds preachy and pedantic on the stump, but his values—respect for law, family, and frugality—are reflected in his more muscular state programs. The second Dukakis administration came on strong with what might be called "gotcha economics." It went after tax delinquents with highly publicized seizures of yachts with Delaware registrations, and unreported limousines and vacation homes. In his current term, Dukakis launched a tough child-support enforcement program. Collections were up 40 percent in the first month. Now his deputies are gearing up to go around to public schools putting the fear of a lifetime of payments into eighteen-yearold boys: before you even think about getting a girl pregnant, remember, child support may be important enough to send you to jail. His most recent effort is establishing a universal health-care system for Massachusetts—the first of its kind in the country.

Governor Dukakis says that any political leader who wants to be president must be a cheerleader in the best sense. Like John Kennedy. Yes, but, I interject in one of our interviews, in the twenty-five years since J.F.K., Americans have learned situational ethics.

"What are situational ethics?'' he asks.

To such dark thoughts Mike Dukakis seems all but impervious. He has a real capacity for incredulity. Gary Hart's behavior was as far from his comprehension as Reagan's invasion of Grenada. "What kind of craziness is that?" he will say. Friends like Lipsitt, expecting a more sophisticated analysis, have to remind themselves, "When it violates his deeply held values, it hits a gut, emotional response."

While his responses on domestic issues are often detailed, with an underpinning of experience, his pronouncements on foreign policy sound like liberal bumper stickers—in a perfect world, reasonable people would sit down and make the Contadora process work in Central America. And we wouldn't be "wandering around in the Persian Gulf bumping into mines." Let Kuwait ask the Russians to run interference for them in the Gulf, he says.

His message restates Reagan's appealing ends, but calls for very different means: a national comeback to optimism, energy, innovation, sacrifice for country, and social utopianism. It is the sort of call to revitalization on which political cycles have turned, every seventeen years or so, from the retreat into privatization, denial of social problems, and old-time religions. The question is, can Mike Dukakis transmit his personal discipline and sacrifice and unswerving confidence to a nation sliding into the twilight of its youthful supremacy?

If any of the Democratic candidates can, Dukakis seems the most likely to do so. The team he might assemble in the White House would surely draw on Massachusetts's competitive edge in advanced education and its cottage industry of raising prize politicos. One can imagine a beehive of idealistic young postgraduates (no BMW-driving yuppies need apply). Unlike Jimmy Carter, to whom Dukakis is often compared, this small man is not threatened by larger-than-life experts or political appointees who get more press than he does—as long as they get the job done. And Kitty Dukakis would unquestionably bring a new dimension to the job of First Lady; she'd be a fiery activist with a love of the arts who knows, from experience, that it's not enough to simply tell 'em "Just say no."

But how do you feel about him? my friends persist in asking.

I find myself answering in the same cautious, self-protective phrases I have heard from veteran idealists all over the country. Peel down the phrases and what is really being said is:

I'm afraid to fall in love again. I've been hurt too often. I can't stand to be made a fool of one more time. They're all so demanding—you give your heart and what happens? Vote for them and you know they won't respect you in the morning. No, at least for the time being, I'd rather go it alone.

After the flirtation with Hart, the fervor for Ferraro, the humiliation with McGovern, the heartbreak over Bobby, the killing of King, the curse stamped on Camelot, and the disillusionment with Reagan—twenty-five years of unrequited, misplaced, or annihilated love—do we really want a leader who appeals to our emotions? Or might we be ready for a hardheaded, thoroughly decent, pre-war model of a man, one who would wear very well indeed, never tell us a lie, give good value on the dollar, and keep Amtrak running on time?

We have waited so long for a political leader to believe in with all our hearts, it may be too late for the Vietnam generation, and even for Dukakis's own Silent Generation, to soften the calluses of cynicism, satire, and sarcasm, to reverse the retreat into personal fantasy. If a good man or qualified woman is hard to find, the even harder task is to suspend disbelief and come down from the bleachers to take another chance.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now