Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGEORGIA ON MY MIND

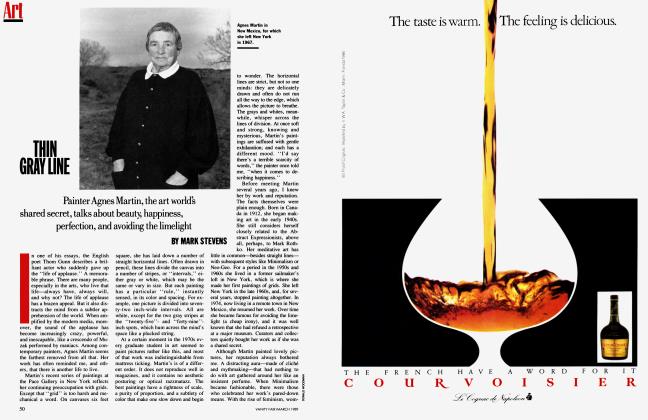

Art

What became her legend most? O'Keeffe's centenary retrospective fans the flame

MARK STEVENS

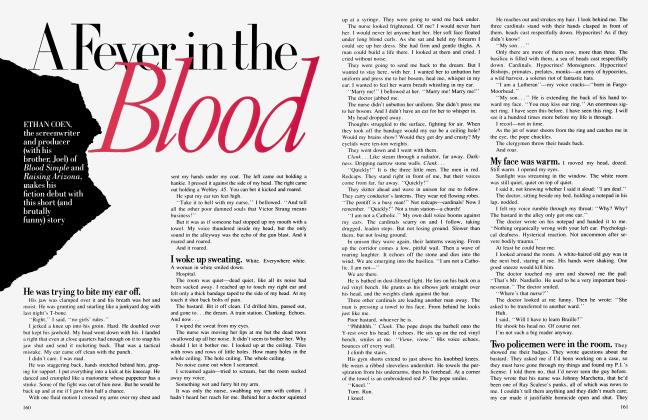

'I walked into the sunset—" the young Georgia O'Keeffe wrote to a friend. It was an emblematic remark. She took other walks, and painted other subjects, but she always returned to the sky. Vast and virginal, O'Keeffe's space is one of ecstatic possibility; the pioneers of legend, while climbing the last rise, might have imagined a similar expanse. Even her down-to-earth subjects—barns or bones or flowers—recall a place where boundaries dissolve and the spirit takes wing. An O'Keeffe flower is no ordinary flower, but a cloud bloom inviting the viewer into its mystery. The smallest watercolors are full of large intimations.

O'Keeffe's importance begins with the painting, but does not end there. Were it only a question of painting, in fact, O'Keeffe would matter less. She was an uneven artist, at times painfully sentimental. By selecting her work carefully, Jack Cowart, the organizer of the large centenary retrospective opening this month at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., hopes to win over the skeptics. Whether he succeeds or not, O'Keeffe will continue to beguile: more than any artist of her time, she recast in her life and work many of the great American themes, and she did so very well. Long before O'Keeffe's death last year at the age of ninety-eight, her life, her art, her prose, her face—what a face—took on a fundamental aspect. She passed into American legend as if by right.

Even the bare facts of O'Keeffe's life have a prophetic flair. She was bom in a town called Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, and she spent a year teaching in Canyon, Texas. Asa young woman she went to the big city—New York—where she married the seminal photographer Alfred Stieglitz and knew the principal American modernists. Although she painted wonderful pictures of New York, she preferred the country. At first, she spent summers with Stieglitz at Lake George in upstate New York. Then she moved west, alone. In New Mexico, she lived to an unearthly age at a place called Ghost Ranch.

It was her unconventional marriage to Stieglitz—and the famous photographs that commemorate it—which first made O'Keeffe seem larger than life. Stieglitz's several hundred pictures of his wife present love in a new light. It is a twentieth-century love, with a modern pulse; it changes and it moves. O'Keeffe is sexy, heartless, canny, wise, stylish, resigned, slatternly, intelligent, pixieish. Sometimes she is an object—aesthetic or sexual—and sometimes a subject. She is naked, dressed, and partially dressed. Again and again we see her face and hands. Stieglitz could no more confine O'Keeffe to one image than Muybridge could capture movement with a single snap of the lens. "His idea of a portrait was not just one picture,'' O'Keeffe said of Stieglitz. "His dream was to start with a child at birth and photograph that child in all of its activities as it grew to be a person and on throughout its adult life."

Her marriage celebrated independence. The sexes were equal, the union a partnership. In the Stieglitz photographs, O'Keeffe never yielded entirely to his camera; she gave only part of herself. Which is unusual: the man with the camera generally owns the woman with the body. Stieglitz may have used the camera erotically ("I was photographed with a kind of heat and excitement," O'Keeffe said), but he could not hope to possess his wife. An essay she wrote in 1978 ends remarkably, if one recalls that she was introducing Stieglitz's portrait of her: "[Stieglitz'sJ eye was in him, and he used it on anything that was nearby. Maybe that way he was always photographing himself." In these photographs, the couple engaged in an exquisite tease; the work of art was a balance of power. It was often O'Keeffe, one feels, who invented the image that Stieglitz recorded.

It would be a mistake, in any case, to refer to the photographer and his model. One would as soon refer to the model and her photographer.

As in art, so in life. Twenty-three years older than O'Keeffe, Stieglitz, a brilliant and volcanic figure, nonetheless encouraged his young wife to keep her name and take herself seriously as an artist. "From the beginning she just felt she was Georgia O'Keeffe, and I agreed with her," Stieglitz said. "She was a person in her own right." The older man—part lover and part father— helped empower the younger woman. Stieglitz's encouragement carried symbolic import for American culture, since women were still largely under the heel. O'Keeffe herself, of course, would accept nothing less than independence. In an early letter to Stieglitz, thanking him for his interest in her work (the catalogue of the exhibition includes 120 heretofore unpublished O'Keeffe letters), she says: "1 like what you write me— Maybe I don't get exactly your meaning—but I like mine—like you liked your interpretation of my drawings. . ." Pretty cocky. Refusing to be patronized, O'Keeffe directed any condescension back where it came from. She often referred to the Stieglitz circle, for example, as the "boys" arguing about art, the implication being that she built the bam while the others just talked.

The reality of the marriage was messier than the myth. It does not seem to have been particularly happy, at least in the later years. Both Stieglitz and O'Keeffe were interested in doing things their way, and each had a different way. He enjoyed company, she liked being alone. He loved talk, she preferred silence. He was intellectual, she was intuitive. He was intentionally American, she was effortlessly American. She wanted a child, he refused. Above all, Stieglitz loved the city, while O'Keeffe required the country. One marriage was not quite large enough for two such people. Listen to the pointed, if lovely, ambivalence in O'Keeffe's description of her husband:

There was such a power when he spoke— people seemed to believe what he said, even when they knew it wasn't their truth. He molded his hearer. They were often speechless. If they crossed him in any way, his power to destroy was as destructive as his power to build—the extremes went together. I have experienced both and survived, but I think I only crossed him when I had to—to survive.

There was a constant grinding like the ocean. It was as if something hot, dark, and destructive was hitched to the highest, brightest star.

For me he was much more wonderful in his work than as a human being. I believe it was the work that kept me with him— though I loved him as a human being.

In the late 1920s and '30s, O'Keeffe began to spend more and more time alone. Pining for prairie and sky, she went to New Mexico for the summers. She and her husband both felt bad about the separations. O'Keeffe "crossed" Stieglitz, as she put it, only "to survive." Yet the didactic importance of the marriage is so great to historians and feminists (in this it resembles the SartreDe Beauvoir union) that even these separations are sometimes regarded as an ideal, as the "space" two creative people may require in order to flourish.

O'Keeffe's marriage, together with her art, helped define the cultural frontiers of the early twentieth century. Upon leaving Stieglitz for the West, O'Keeffe invoked yet another quintessentially American frontier. In Western movies, the man of few words leaves behind a woman and a town (civilization) to pursue a dream in the wilderness: "A man's got to do what a man's got to do." O'Keeffe struck this classic pose—she just switched the sexes. Exchanging husband for solitude, city for country, and, in a way, Europe for America, O'Keeffe came to embody the pioneer spirit.

O'Keeffe looked the pioneer part. Over the years the sun, wind, and rain puckered her up until she resembled an old, weathered fence post.

Of course, the actual frontier had long since disappeared, though life remained pleasantly rough. ("The bridges here are only wide enough for angels to fly over," she wrote Paul Strand.) What's more, countless predecessors had already used the land as a metaphor for the sublime. If O'Keeffe was a little late, she still found ways to replay the oldtime music. Like many artists of the period, she was interested in spiritual frontiers—which do not disappear—and she was able to restate the traditional American sublime with modernist means. At the same time, she settled in a particularly foreign part of the West. Still a largely Indian and Hispanic land, austere and death-haunted, New Mexico had a spiritual tradition far different from the New England transcendentalism that infused nineteenth-century American landscape painting.

O'Keeffe's New Mexico paintings were at once simple and sophisticated, naive and stylish, stringent and voluptuous, empty and full—the classic American contrasts. In her approach to art, O'Keeffe seemed both pragmatic and idealistic, a down-to-earth painter with faraway eyes. She shared with many of the nineteenthcentury painters an obsession with both finely rendered details and the mystical smudge on the horizon. Foreground and background appealed to her more than the middle distance. In trying to suggest the whole, she typically relied on the part and had no qualms about cropping a mountain or a church. In almost every painting there was something hard, a spiky bone or a sharp line, and something soft, a melting color or a patch of sky seen through the holes in a skull.

O 'Keeffe herself fit the pioneer part: she had all the right prejudices. As StiegWlitz had discovered, she liked being alone, and much preferred land to people. As early as 1916, writing to Stieglitz from Canyon, Texas, she made her priorities clear: "I feel its [A/C] a pity to disfigure such wonderful country with people of any kind—" Later in the letter she pays Stieglitz the highest compliment: "You are more the size of the plains than most folks—"

She couldn't have cared less—or pretended not to care less—about what others thought of her. Disgusted with the Freudian interpretations of her work— which described the famous flower paintings as vaginal—she claimed to hold two exhibitions, the first in her own mind, the second for the interpreting public. In 1927 she wrote: "My exhibition goes up today or tomorrow—It is too beautiful—I hope the next one will not be beautiful... I would like the next one to be so magnificently vulgar that all the people who have liked what I have been doing would stop speaking to me— My feeling today is that if I could do that I would be a great success to myself—" O'Keeffe also looked the pioneer part. The face had plenty of flint (the body had a hidden softness that Stieglitz revealed), and over the years the sun, wind, and rain puckered her up until she resembled an old, weathered fence post. Her dour, canny expression was right, too. What nonsense is this? she seemed to ask the camera. Like any good pioneer, O'Keeffe kept her cards close to the vest and her eyes on the main chance. On those rare occasions when a photographer caught her in a half-smile, it was like a shot of sun through the clouds.

More subtle, but still important, was her pioneer's voice. O'Keeffe wrote as if to talk. Pleasingly gruff, inflected with a midwestem twang, and as quirky as a grasshopper, the voice in her writing evoked a long-vanished America. O'Keeffe had no patience for commas; her sentences hopped with dashes as she jumped from thought to thought. "Tonight I walked into the sunset—to mail some letters—the whole sky—and there is so much of it out here—was just blazing—and grey blue clouds were rioting all through the hotness of it—and the ugly little buildings and windmills looked great against it." Like other pioneers, she depended on understatement. (Note the downbeat "to mail some letters" after the upbeat "I walked into the sunset.") Or, put another way, she did not trust words. "Words and I are not good friends at all except with some people—when Im [s/c] close to them and can feel as well as hear their response—"

What she left out always seemed important. As in the paintings, the part stood for the whole. She spoke by ellipsis, implication, reticence. Fancy words were for fakes. In fact, she often sounded like another plainspoken Midwesterner who loved the western myth, a man a little younger than she—Ernest Hemingway. Like him, she used small words to say big things and got a simple rhythm going that sounded as honest as, well, the day is long. In 1915 she described a friend this way: "He gave me so many new things to think about and we never fussed and never got slushy so I had a beautiful time and guess he did too—" It was a tinny rhyme, to be sure, and, not surprisingly, the gossip has always run against Hamilton. Why, it was whispered, would this unknown potter spend so much time with an ancient woman if not to inherit her estate and make important connections in the art world? Her estate was valued at $65 million, and there were indeed codicils to the will that benefited Hamilton. When a court settled the disputed estate last summer, he emerged a wealthy man. He will receive twenty-four paintings, the Ghost Ranch, along with certain copyrights, correspondence, and works by other artists. But why not? O'Keeffe was not close to her family, and Hamilton appeared genuinely devoted. He made the end of O'Keeffe's life as happy as it could have been. (One remembers her years alone and her desire for a child.) If he used her, then she used him, and it was probably a warming arrangement all around. More interesting was why the Hamilton story titillates. The answer was that over three decades O'Keeffe slowly aged into glamour, the Garbo of the West. (Imagine if Garbo had a young man.) The glamour gave particular interest to the ugly if inevitable curiosity— were they. .. uh.. . you know. . . ?

O'Keeffe became in the public eye what Santa Fe is now—a stylized version of the simple life, the desert green with money.

Georgia O'Keeffe did not try to become a legend. Most of her time in Abiquiu was spent alone. In the 1950s, the world did not pay her too much mind. During the last twenty years, however, something strange and almost sad happened. Reporters, feminists, art historians, and other sightseers discovered the pioneer in Abiquiu. She probably began to enjoy her own myth, for she started to become a little too mannered, a little too precious. In America, what begins as myth often ends as kitsch.

The younger O'Keeffe had been both stylish and plain. It was part of her achievement to blend those values. Now the paradoxes that had once enriched her sensibility appeared as fault lines. The simplicity seemed showy, the integrity obvious, the privacy public. O'Keeffe developed what might be called an aesthetic of the ascetic. Always conscious of her dress, she now became too gorgeously severe in her flowing black-and-white: Our Lady of the Desert. A true ascetic would not have been so calculating, or would have worried about the calculation. Never less than wily about her career, she now took too great an interest in her fortunes. Like Hemingway, who ended up playing himself, O'Keeffe began to overstate the understatement.

Still a favorite model for photographers, she continued to play to the camera, but there was no more test of strength, no more exquisite tension. O'Keeffe overpowered her photographers. The later pictures were stagy, pretentious, and sentimental. O'Keeffe stared into space as if God himself were whispering into her ear. Or she cut a touching figure against miles of mountain. The wrinkles advertised integrity. Bad photographers always got good picturesque, with O'Keeffe's help.

The most remarkable repetition— when myth really declined into kitsch— was her relationship with Juan Hamilton. As a celebrated octogenarian, O'Keeffe fell in love with a twenty-seven-year-old potter; this rhymed with the Stieglitz relationship, in which a celebrated older photographer fell in love with a much younger painter. Hamilton and O'Keeffe saw each other almost daily, and even traveled to the Caribbean together. He helped manage her career, and after her death he guided the dispersal of her paintings, just as O'Keeffe oversaw the dissemination of Stieglitz's work.

O'Keeffe became in the public eye what Santa Fe is now—a stylized version of the simple life, the desert green with money. As glamour went, she was top-of-the-line. No one was a better grand-old-profound-woman-artist: Louise Nevelson was only a distant second. By the end, Calvin Klein, who revered but had never met O'Keeffe, was giving her presents. Eventually she greeted him at the door of her house wearing one of his creations. So great was Klein's reverence, in fact, that he created an advertising campaign (with himself as the model) which was shot in her house. And now Steven Spielberg is doing the movie.

It's depressing enough to make one want to blame O'Keeffe. But that would be a mistake: any change in O'Keeffe herself was very small, a matter only of degree. (Besides, there's no need to be perfect; sometimes Whitman was just a megaphone.) It was the culture around O'Keeffe that did most of the changing. With effort, however, it's still possible to see O'Keeffe through the hagiographic haze. Her art, for all its faults, remains fascinating. It recalls the painting of William Blake, who was also criticized for his execution and excess. In each case, the spiritual intensity holds the mind and eye. O'Keeffe, like Blake, was not embarrassed by angels. She did not steel herself with irony. "Isn't it curious," she wrote a friend in 1915, "the way we are always afraid someone will think the most serious—earnest ideas we have—are silly—"

The apotheosis of Georgia O'Keeffe —at the exhibition in Washington we can expect the heavenly host, presided over by the solemn spirit of an Indian brave, to welcome her into the American empyrean—has a simple poignance. She became a legend because the values she represents are no longer alive. She really was the last pioneer, even if they used her to sell tickets at the end.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now