Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBlack Comedy

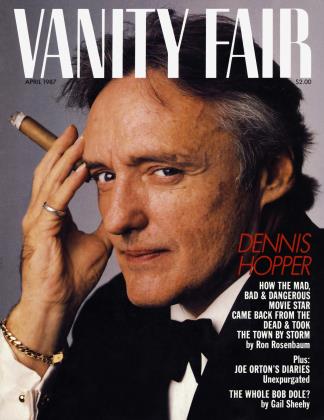

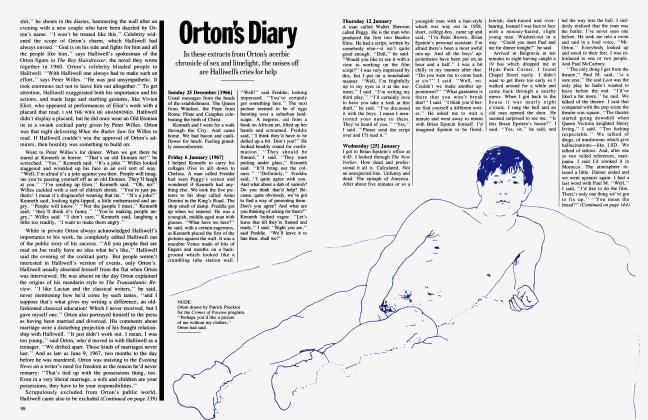

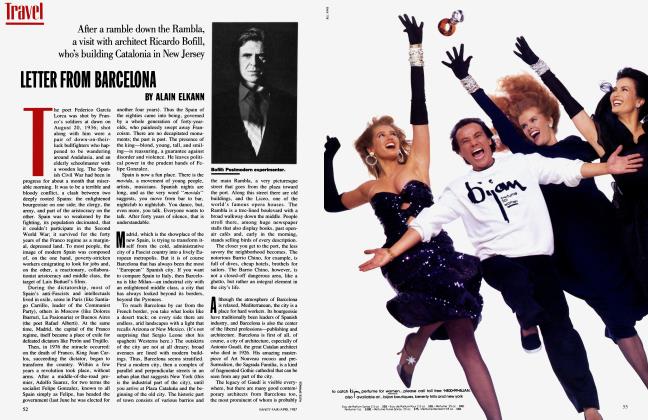

Play wright Joe Orton was the Oscar Wilde of the sixties, a cruelly funny ruffian on the stairway to success—until his violent death at the hands of his lover, I "middle-aged nonentity" Kenneth Halliwell. No one knew then that the tortured relationship with Halliwell was Orton's direct inspiration. Overleaf, JOHN LAHR explores the twists and turns that drove the Halliwell-Orton symbiosis. On page 98 there are extracts from the Orton diaries (out this month from Harper & Row). Also this month a startling new movie, Prick Up Your Ears, will finally put Halliwell alongside Orton in the limelight he craved.

I'm going up, up, up," wrote Joe Orton in October 1966, after the revival of Loot, his second full-length play, became the London West End's comedy hit of the year. It was a miraculous rebirth of a play the critics had pronounced dead on arrival only eighteen months before. With it, Orton too was reborn. He had found a way of making his rambunctiousness and rage acceptable in a lethal, epigrammatic style: "All classes are criminal today. We live in an age of equality." But Orton's change of direction only magnified the distance between him and his friend of sixteen years, Kenneth Halliwell. Halliwell was Orton's mentor, his benefactor, and, finally, his killer. Together they had worked for fame, but only Orton had the luck of talent. They shared everything but success. Orton was celebrated, and Halliwell had nothing to show for his input into Orton's work. For the public, anyway, Halliwell was a nonperson. Orton told the press he'd been married and divorced. But on August 9, 1967, Halliwell linked his name finally and forever to Orton's genius, by staving his head with nine hammer blows and then taking his own life with a massive overdose of Nembutals. On top of Orton's diary, Halliwell had left a note: "If you read his diary all will be explained. P.S. Especially the latter part."

Orton held nothing back in public but Halliwell. The diaries only confirmed Halliwell's declining influence in Orton's life. Once, as Orton's tutor and boon companion, Halliwell had been the center of it, and now he was increasingly an extra in Orton's epic. The diaries are full of Orton's sexual and theatrical triumphs: Loot voted best play and sold to the movies; Entertaining Mr. Sloane, his scandalous first full-length play, which made his name, sold to TV; the Beatles approaching him to write a screenplay; his third and best full-length play, What the Butler Saw, writing itself easily. Everything, even the failed novels they had written together, could be turned to Orton's advantage. Long before Orton could deliver his lethal wit, he dreamed of sentences "capable of killing centuries afterwards." Revenge was at the heart of Orton's humor, a trickster's desire to marry terror and elation, to test all boundaries. Halliwell had encouraged Orton's mischief and erudition for his own amusement, and he watched, bewildered, as the public replaced him as an audience for Orton's high jinks. Orton had willed himself into the role of rebel outcast, beyond guilt or shame. At thirty-four, after serving a term in prison for comically defacing public-library books, he had rejected the world of conventional work, conventional sex, and conventional wisdom. He became an iconoclast who believed there was no sense being a rebel without applause. He had found an audience; but Halliwell, bald and overbearing at forty-one, could attract no public and few friends.

The success of Loot (which was Halliwell's title) emboldened Orton. Just four months before the revival of Loot, he had been threatening to quit the theater. "I'm really quite capable of carrying this out," he wrote to his agent, Peggy Ramsay. "I've always admired Congreve who, after the absolute failure of Way of the World, just stopped writing. And Rimbaud who turned his back on the literary world after writing a few volumes." Before Loot's success, Orton had been promising; now he was suddenly major. His literary style and his life acquired a new amperage. He was at the top of his form, full of fun, and writing like the young master he knew himself to be. The buoyant outrageousness of his comic style evolved mostly in the last eight, fecund months of his life. In that time, besides keeping the diaries, Orton wrote Funeral Games, a ghoulish capriccio about faith and justice; rewrote his first play, The Ruffian on the Stair, and The Erpingham Camp to 'go with it, under the collective title Crimes of Passion; completed a screenplay for the Beatles, Up Against It; and wrote his farce masterpiece, What the Butler Saw. Orton's plays caught the era's psychopathic mood, that restless, ruthless pursuit of sensation whose manic frivolity announced a refusal to suffer. His diaries are a chronicle not only of a unique comic imagination but of the cockeyed liberty of the time—a time before the failure of radical politics, before mass unemployment, before AIDS.

I don't write fantasy" Orton's comic world, with its monsters of power and propriety was all around him.

The idea of a diary, which Orton entitled Diary of a Somebody, was first suggested by Peggy Ramsay in 1965 as Orton and Halliwell were leaving for a vacation in North Africa. "I didn't write up the Morocco diary as you wanted," Orton wrote to her in August of that year. ''I thought there might be difficulties in getting it published." Ramsay continued to press for an account of their adventures, if not from Orton, then from Halliwell, whose literary ambitions Orton had inherited and then surpassed. "I urge one of you, at least, to start a Journal, a la Gide; I'm sure it would be a good idea and the publishers would snap at it," she wrote Orton, prematurely, as it turned out. "Why not talk this over with Ken, who has real writing talent, but finds stage plots difficult?"

Halliwell, however, was fast losing what literary confidence he had left. His latest rejection had come the day after Loot opened to phenomenal reviews, and was from Ramsay herself. "What I've read," she wrote, too bored to finish Halliwell's The Facts of Life, "reads like an adaptation from a novel, because the first speech, for instance, is so damned literary and the speeches are nearly always written beyond their 'holding' capacity." Before Halliwell finally gave up writing, he sent the play to a few more agents and to Peter Willes, who produced Orton's television plays. "I'd had several plays sent me by Ken," Peter Willes recalls. "They were not like Joe's whatsoever. They were like very pseudo-Ronald Firbank."

Halliwell, who never found himself, also never found his literary voice. Orton did. Orton's unrelenting display of verbal prowess was a terrific offense which masked his defensiveness; but Halliwell's literary archness only made his insecurity more transparent. Between October and December 1966, when the diary began, Halliwell abdicated the literary obsession that had dominated their adult lives and concentrated on making collages. "Does my real talent if any lie in this direction," he wrote to Peggy Ramsay on September 30. Orton was now the writer, and Halliwell, who had nurtured Orton's skills and ambitions, was increasingly a factotum. Inevitably, the diary suggested by Ramsay became Orton's project.

"I'm keeping a journal," Orton wrote to Peggy Ramsay from Tangier on May 26, 1967, five months after he'd begun it, adding, "to be published long after my death." To Orton, the value of a diary was its frankness. Reality, as his plays insisted, was the ultimate outrage. Orton despised the bogus propriety—the "verbal asterisks"—with which public figures doctored the picture of their life. "It's extraordinary," he complained to Ramsay, "how, as people grow older and they have less to lose by telling the truth, they grow more discreet, not less." To Orton, indiscretion was the better part of valor. "The whole trouble with Western Society today is the lack of anything worth concealing," he wrote in his diary, which revealed everything but Halliwell's legitimate demand to be acknowledged for his contribution to Orton's work.

"When Joe sent me Sloane, he spoke of it as 'our play,' " says Peggy Ramsay. "The first time he came to see me, Joe didn't produce Kenneth. But the second time he said, 'Can I bring my friend?' And never at any stage was Kenneth not there." Orton dedicated Entertaining Mr. Sloane to Halliwell, and Halliwell sometimes talked of "a genius like us." In 1965, nervous about the Broadway reception of Sloane, Orton wrote to Halliwell from New York: "I'm not hopeful of success. But then we never were, were we." And when the original production of Loot faced its first audiences in Cambridge, Orton's distraught letters home to Halliwell register a tone of dependence and concern that is nowhere in the diaries: "The play is a disaster. There were hardly any laughs for Truscott. The audience seemed to take the most extraordinary lines with dead seriousness.... I shall have to do some surgery. I can't come back Wednesday. Can't you ring me? It's all so dreadful. I've already had two rows of nerve-wracking proportions. I've said to [the director, Peter] Wood that I'm not a commercial writer and perhaps he understands now why it's impossible that I should ever be a 'National humourist.'.. .I'm going to try and get back before the weekend, but I can't leave with it in this state." From Oxford the news was no better, but Orton's tone had the same solicitousness. "Do try and hang on doing something if you get too fed up without me," he wrote, signing off, "Love, Joe." "I'll get back as soon as humanly possible. I'm not gallivanting about down here. It's the most depressing few weeks I've ever lived through."

Orton had the big bank balance, the big name and the big future

Halliwell had to share Orton with a new lover the public.

But when Orton's luck changed, so did his relationship with Halliwell. "Joe had only one overwhelming relationship allied to loyalty, and that was Ken," said Peggy Ramsay. "He didn't care a damn about anybody else." Orton remained loyal in his fashion to Halliwell, but once he was in the public gaze he couldn't bring himself to acknowledge the collaboration that had made his success possible. Orton could cure himself of many of the culture's deliriums, but not its romance of self.

History is not kind to those who are sacrificed to someone else's art. Emma Hardy was seen as a vituperative, no-talent ninny; Vivien Eliot as the loony baggage the great poet was lumbered with; and Halliwell as a "middle-aged nonentity." They were all silent partners of admired artists, and they all had literary ambitions of their own. They stuck with their literary marriages in part because the other partner fulfilled a dream and in part because they had helped fulfill it. But their collaboration became an alienation. This was especially true of Halliwell, who had worked a lifetime to create art and whose great creation was Orton. Halliwell supposed that with Orton's success some residual kudos would come to him. But he had to share Orton with a new lover—the public. "If he belongs to the public in any way," Emma Hardy wrote to a friend, counseling her not to expect gratitude, attention, or justice from her marriage, "years of devotion count for nothing." Halliwell found himself forced into a position of being at once invisible and unwanted. "I hated Halliwell. No, I disliked him—he wasn't important enough to hate," says Peter Willes. "I put up with Halliwell the way one does with authors' wives if you want their work."

Halliwell was experiencing the desperation of many partners of the famous: discounted in public, they go quietly mad in private. "Everyone wanted to meet Joe—Emlyn Williams, Pinter, Rattigan," says Peter Willes. "I introduced Harold to Joe. Harold said, 'I couldn't believe he was so young.' Joe looked much younger than he was." But Halliwell looked old, and irrelevant. "They treated me like shit," he shouts in the diaries, hammering the wall after an evening with a new couple who have been dazzled by Orton's name. "I won't be treated like this." Celebrity widened the scope of Orton's charm, which Halliwell had always envied. "God is on his side and fights for him and all the people like him," says Halliwell's spokesman of the Orton figure in The Boy Hairdresser, the novel they wrote together in 1960. Orton's celebrity blinded people to Halliwell. "With Halliwell one always had to make such an effort," says Peter Willes. "He was just unsympathetic. It took enormous tact not to leave him out altogether." To get attention, Halliwell exaggerated both his importance and his actions, and made large and startling gestures, like Vivien Eliot, who appeared at performances of Eliot's work with a placard that read, I AM THE WIFE HE ABANDONED. Halliwell didn't display a placard, but he did once wear an Old Etonian tie to a swank cocktail party given by Peter Willes. Orton was that night delivering What the Butler Saw for Willes to read. If Halliwell couldn't win the approval of Orton's admirers, then hostility was something to build on:

Went to Peter Willes's for dinner. When we got there he stared at Kenneth in horror. "That's an old Etonian tie!" he screeched. "Yes," Kenneth said. "It's a joke." Willes looked staggered and wrinkled up his face in an evil sort of way. "Well, I'm afraid it's a joke against you then. People will imagine you're passing yourself off as an old Etonian. They'll laugh at you." "I'm sending up Eton," Kenneth said. "Oh, no!" Willes cackled with a sort of eldritch shriek. "You're just pathetic! I mean it's disgraceful wearing that tie." "It's a joke!" Kenneth said, looking tight-lipped, a little embarrassed and angry. "People will know." "Not the people I meet," Kenneth said, "they'll think it's funny." "You're making people angry," Willes said. "I don't care," Kenneth said, laughing a little too readily, "I want to make them angry."

While in private Orton always acknowledged Halliwell's importance to his work, he completely edited Halliwell out of the public story of his success. "All you people that are mad on Joe really have no idea what he's like," Halliwell said the evening of the cocktail party. But people weren't interested in Halliwell's version of events, only Orton's. Halliwell usually absented himself from the flat when Orton was interviewed. He was absent on the day Orton explained the origins of his mandarin style to The Transatlantic Review. "I like Lucian and the classical writers," he said, never mentioning how he'd come by such tastes, "and I suppose that's what gives my writing a difference, an oldfashioned classical education! Which I never received, but I gave myself one." Orton also portrayed himself to the press as having been married and divorced. His comments about marriage were a disturbing projection of his fraught relationship with Halliwell. "It just didn't work out. I mean, I was too young," said Orton, who'd moved in with Halliwell as a teenager. "We drifted apart. Those kinds of marriages never last." And as late as June 9, 1967, two months to the day before he was murdered, Orton was insisting to the Evening News on a writer's need for freedom as the reason he'd never remarry: "That's tied up with the possessions thing, too. Even in a very liberal marriage, a wife and children are your possessions, they have to be your responsibilities."

Scrupulously excluded from Orton's public world, Halliwell came also to be excluded from Orton's social world. "Joe was very protective of Halliwell," says Peter Willes. "He wouldn't go anywhere without him. He didn't care if he gave a bad impression. It was 'Take me as you find me.' " But in the last weeks of his life, Orton agreed to attend, without Halliwell, a party of show-biz luminaries given by the former American musical-comedy star Dorothy Dickson. He was killed within a week of the party. Peter Willes, who helped organize the party, remembers Halliwell landing on his doorstep on August 7. "Ken came to see me while waiting to get a prescription of tranquilizers filled. 'You don't realize how Joe carries on at the thought of separating. You don't realize how dependent he is on me.' I couldn't wait to get Halliwell out of the flat. I felt I wanted to disinfect the place. I telephoned Joe and said, 'Listen, you can't leave Kenneth and come to the party.' That was the first time I knew for sure that I was talking to Joe on the telephone, because Kenneth had just left my flat. Ken imitated Joe's voice on the phone—they sounded just alike—and you had to be careful. He wanted to find out what people were saying to Joe— anything that might possibly affect their life together. ' '

Continued on page 139

Continued from page 98

The famous leave around them shattered lives, which are either overlooked or underplayed by biographers, or rewritten by the celebrities themselves. After Emma Hardy's death, Thomas Hardy burned her diary testimony, which was said to be entitled "What I Think of My Husband," ghosted his own biography, and recast the barbarity of their relationship into fine poetry. Eliot sealed his past in silence by stipulating in his will that he wanted no biography. Orton never had time to rewrite history, so his diaries offer a rare, if unwitting, glimpse into the punishing dynamic of celebrity's self-aggrandizement. As Halliwell's suicide note implies ("If you read his diary all will be explained"), the diaries were both an explanation and a provocation. Orton owned the future, the past, and now even Halliwell's suffering.

The diaries are not just a chronicle of the drama between them, but a prop in it. Orton and Halliwell lived in extraordinary physical proximity; their room was sixteen by twelve. The bulk of the diaries was written virtually under Halliwell's nose, and they were kept in a red leather binder in the writing desk, where Halliwell could—and did—read their punishing contents. Everything about the diaries was provocative; they became a symbol of Orton's retreat into himself and away from Halliwell. The title, which emphasized Orton's singularity, was also a reminder that if Orton was somebody, by implication Halliwell was nobody. Orton was the center of Halliwell's life; but, as the diaries indicate, Halliwell was an increasingly minor—and frequently irritating—extra in the drama of Orton's eventful life.

Inevitably, Orton's memory is selective. His accounts of Halliwell's depression—the rows, the nagging, the brittle hauteur—are well documented, but the issues behind these scenes are kept very much offstage. "Halliwell felt he was excluded somehow and not valued," says Dr. Douglas Ismay, a G.P. with an interest in psychology to whom Peter Willes had sent Halliwell for help, and who gave Halliwell Tofranil and sympathy. "People didn't know he helped to write and edit some of the plays. He said that Orton was a much less well educated person than he was, and Orton drew on his know-how and grasp of English. He felt frustrated." Although in the diaries Orton acknowledges Halliwell's critical acumen, he mentions none of Halliwell's artistic claims. In Orton's version of his daily life, Halliwell is shown merely as an accoutrement. And by then he was. But the Beatles' screenplay, Up Against It, was based, in part, on their first novel, written in 1953, when the only thing Orton could contribute to the collaboration was his typing. The Ruffian on the Stair, which Orton polished for the Royal Court, was adapted from their novel The Boy Hairdresser. Sloane was, according to Orton, "our play." Even Orton's wonderful gift for dialogue owed its power to collage, which was originally Halliwell's fascination. Halliwell had been completely taken over by the imperialism of Orton's fame. ("Must make it plain," Halliwell wrote to Peggy Ramsay in a letter asking her to assess his collage murals, "this invite is not from J or anything to do with him or his Works.") On that painful issue, Orton in the diaries remains mum. According to Dr. Ismay, Halliwell "said that Orton thought he was a pain in his side, a nuisance who was interfering with Orton's success." Orton rarely states his feelings in the diaries. Instead, he signals his disaffection in small asides ("Kenneth quel moan") and throwaway snatches of sour conversation—never in print probing Halliwell's complaints too deeply. "You look like a zombie," the diary reports Orton saying to Halliwell on April 23. "He replied, 'So I should. I lead the life of a zombie.' " Whether Halliwell is crying on the terrace of a Tangier restaurant, or creating a scene at Peter Willes's home, or threatening suicide, his emotional pressure on Orton is as apparent as Orton's refusal to be moved by it. The "tranquillisers worked against too much yapping," Orton writes on the day of the "zombie" exchange.

But the diaries are also an extraordinary record of Orton's sexual adventures—his way not just of keeping count but of recapturing desire. "At one moment," Orton writes on June 11 of an encounter with an Arab boy in Tangier, "with my cock in his arse, the image was, and as I write still is, overpoweringly erotic." Halliwell hated this side of Orton. "He was disgusted more and more with Orton's promiscuity," says Dr. Ismay. "The public-lavatory theme was the thing that bothered him most." Orton insisted that the trolling fed his work, but it also fed Halliwell's rage. "I'm disgusted by all this immorality," Halliwell shouts at Orton after an anticlimactic dinner on May 1 with two homosexual acquaintances of Orton's. "Homosexuals disgust me!" Promiscuity exacerbated not only Halliwell's sense of sexual guilt but his sense of sexual inadequacy. Halliwell may have been the focus of Orton's affections, but never of his sexual desire. "Kenneth knew that Joe didn't reciprocate his romantic attachment in any way," says Peter Willes. "Joe had no feeling for him except protection and loyalty." But the issue of sexual prowess became an infighting point between them. When Halliwell loudly claims in front of the Loot cast that Orton isn't oversexed, Orton takes umbrage; likewise, Orton is angered by Halliwell's bravado on the subject of young male prostitutes in Tangier:

Kenneth said, "Oh, all the boys will do anything." "They won't," I said. "There's a lot of things they won't do." It was very irritating to be told by someone who likes being masturbated that the boys "will do anything."

This gibe about Halli well's prowess precipitated the first of Halli well's violent attacks on Orton.

Orton instinctively taunted the bogus; and promiscuity was, on some level, a way of taunting and testing what he saw as Halliwell's illusion of their family unit. "The household they had was a fake household, and Joe knew this," says Penelope Gilliatt, who befriended Orton when she was drama critic of the Observer. "Joe knew the fakery well enough to kick it about and endanger it as much as possible by staying out late, by promiscuity, by every means he could. To see how far he could drive Halliwell. I think Joe hated himself for accepting domesticity and carrying on with it." The diaries brought Orton's promiscuity off the streets and under their roof. The fact that he described these scenes with such humor and insight only compounded the problem. Orton was making a legend of something profoundly undermining to Halliwell. He was writing down these scenes—and relishing them in set pieces of conversation—while Halliwell was at the same time acting out his desperation to be loved. It was a dangerous game. Orton was flirting with death not only in the public lavatories but with Halliwell at home. He and Halliwell had already explored the murderous parameters of Halliwell's self-loathing and possessiveness in The Boy Hairdresser. They had already imagined their deaths in print—Orton's "beauty smashed forever" and Halliwell dreaming of one crazy act of revenge before killing himself: "When he went, he'd take others with him... the last laugh had to be played correctly."

In their novel, the revenge is botched; in life, it wasn't. The diaries were the focus of both of Halliwell's attacks on Orton. The first, in Tangier, took place while Orton was actually writing in the diary, with Halliwell "hitting me about the head and knocking my pen from my hand." After the second attack, Halliwell placed his suicide note directly on top of the diaries, directing police to them as an explanation for the bludgeoning.

rrthe diaries pick up Orton's story just JL after the power in the two men's relationship had shifted irrevocably in Orton's favor. Orton had the big bank balance, the big name, and the big future. All the calls and letters were for him. Halliwell, who had been Orton's mentor, was now his employee. "When I said, 'What's your job?' " recalls Dr. Ismay of his first meeting with Halliwell, "he said, 'I'm a secretary.' Later it transpired that he was a writer." By the time of the diaries, Halliwell's resentments and frustrations had changed Orton's tone from one of comradely dependence to forbearance ("When we got home we had a cup of tea and it was smiles until bedtime"). In the diaries, Orton continually looks at Halliwell and finds him lacking. Halliwell's whining, his prissiness, his self-consciousness, his bombast are all noted in Orton's asides. And when Orton forthrightly defends Halliwell against the slander of being a "middle-aged nonentity," he is compelled to add, "Kenneth has more talent, although it's hidden."

There was nothing hidden about Halli well's talent when they first met, at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in 1951. Halliwell was twenty-five and imposing in his bravado and his baldness. Orton was eighteen, the first of four children from a working-class Leicester family where there was never enough money or attention to go around. He was a raw kid who'd never spent two weeks away from home. To him, Halliwell was promise incarnate. He had everything Orton lacked: his own flat, a car, a library, an education. He also had a good line in literary chat. Halliwell spouted the kind of romantic idealism he put into his play about Edmund Kean, The Protagonist: "This is the end to which my being has been directed: the acclamation of the world and nothing less." And he preached the gospel of Art, at least until he became its victim. "If a man must, by the very nature of his work, live more intensely than others, may not extravagances be forgiven in him, which would be blameworthy in others?" Orton became his acolyte.

Halliwell's possessiveness and desire to control were the result of the traumatic abandonments of his childhood. His mother died in 1937, when he was eleven, of a wasp sting on her finger, inflicted while she was making breakfast. With her death, according to their lodger, J. P. Howarth, Halliwell "became very introspective and difficult to talk to." He and his father had little to say to each other. They lived as strangers under the same roof. Halliwell studied hard at the Wirral Grammar School and did well, earning his Higher School Certificate in ancient history, Greek, Latin, and German. One morning in 1943, he came downstairs to find his father lying dead with his head in the oven. With typical reticence, the taciturn Mr. Halliwell had left no note. Inevitably, after such overwhelming rejections, Halliwell found refuge in grandiose fantasy. His mother had wanted him to be a doctor. His father had quarreled with him about his decision not to follow an academic path. But Halliwell had his heart set on the glory road, which would lead him nowhere.

"Tight is the word that comes to mind for Halliwell," said Charles Marowitz, the director of the first London production of Loot. "He was organizing his social persona so vigorously, so forcefully, that I never once saw him in repose. He could never unclench." Even as a teenager, Halliwell was grave. At RADA, he was all perspiration and no inspiration when he was onstage. He was older than most of the students, and his high-handed manner kept them at a distance. What Orton saw in him as intellectual authority came across to more sophisticated students as hapless insecurity. "He was a very affected little man," says Margaret Whiting, who won the Bancroft Medal for being the outstanding performer of their year. "He had visions of grandeur. He was always in his little world of creative fantasy. He was so selfish and so preoccupied about himself. He was a great egotist."

Orton, with his threadbare resources, saw Halliwell as a teacher, a father, and a friend. And Halliwell, an orphan, found in Orton someone willing to share his life and his dreams of glory. Orton was vivacious and charming; and, as they wrote in The Boy Hairdresser, reconstructing the origins of their relationship, Orton "made him feel young." He also made Halliwell feel powerful, because "he was in need of protection." Orton, as depicted in The Boy Hairdresser, "was half-educated, half-baked, half-cut." To educate him gave them both a mission and a bond. They became united in their desire to be special.

"I never was able to imagine myself being ordinary," said Orton. He got this idea from his mother, Elsie, who looked upon "her John" as the most gifted of her children. Elsie, a char, refused to admit the ordinariness of her life or her children. She was always in search of some indication of status: Player's, not Woodbines; ham, not Spam; opera, not Gilbert and Sullivan. She wanted the best, but she'd been shortchanged in life. Her family had no money, no education, no prospects. When Orton failed his eleven-plus exam, which meant that his secondary education would be nonacademic, Elsie pawned her wedding ring so that her son could be the only boy on his Leicester council estate of 1,500 to attend a fee-paying school. Typically, Elsie chose Clark's College, which offered a commercial curriculum, not the academic course she'd intended. In his plays, Orton mocked his mother's pretensions to propriety, but he worked to fulfill the generalized ambition he'd absorbed from her. At fifteen, before he'd even appeared in a play, Orton had dedicated his life—so he wrote in his teenage diary—to the theater. He was looking for a way out of Leicester and for a new family. He found it with Halliwell.

"If we could pool our resources, we could help each other," says Halliwell's spokesman in The Boy Hairdresser. Orton's contribution, at first, was enthusiasm and attention. Halliwell exerted almost complete control over the relationship; he cooked and provided the food. More than that, as Lawrence Griffin, who shared their first flat, at 161 West End Lane in London, recalls, "Halliwell showed Orton what to wear, what to read, where to go." The price Orton paid for this largess was loyalty. Halliwell, who called him "my pussycat," kept Orton on a tight leash. "Kenneth Halliwell didn't like John being away," Griffin says. "You could see Halliwell was jealous. John didn't bridle. It was useful. It was a base to go back to. He was, like Sloane, a tease." Peter Willes agrees: "Joe was Sloane, ruthless, not immoral but amoral, and pragmatic." Orton followed the line of least resistance, and, like Sloane, was maneuvered into a situation he'd never bargained for.

"They had the idea they were going to be brilliant actors," says Griffin. "Sometimes I used to feel the odd one out, because they practically convinced me they were so good. They looked upon themselves as very special." When their acting dreams collapsed, Orton and Halliwell fixed on writing. Cocooned in their room and their dream of literary success, they began to write and make a study of literature. "Escape unaided," wrote Orton in the early sixties in Head to Toe, his posthumously published novel, "had never occurred to Gombold." Nor had it occurred to Orton. After a while their regimen of writing and reading became habit, and Orton, like Gombold, "never now mentioned escape; study took the place of liberty; absorbed in acquiring knowledge, days, months and years passed in one rapid and instructive course." Orton's fictional characters "slithered into what they hoped was freedom." They didn't find it; and neither did Orton and Halliwell. For them freedom meant success, and it completely eluded them. They published nothing. Their hostility—in the form of the comic defacement of public-library books—landed them in an actual, not an imagined, cell. In 1962 they were sent to separate prisons for six months. It was the first time Orton had been away from Halliwell for a sustained period of time. In jail, on his own, Halliwell grew depressed, and soon after his release he attempted suicide. But Orton learned something about himself that brought detachment and boldness to his writings: "Before, I had been vaguely conscious of something rotten somewhere: prison crystallised this. The old whore society really lifted up her skirts, and the stench was pretty foul." For Orton, the experience was a liberation. "Being in the nick brought detachment to my writing," he told the Leicester Mercury. "I wasn't involved anymore, and it suddenly worked." Orton had passed beyond suffering. He now had nothing to lose. His laughter became dangerous. He had at last found a way to "rage correctly."

"I don't write fantasy," Orton said. "People think I do, but I don't." The diaries confirm this. Orton's comic world, with its monsters of power and propriety, was all around him. He heard his brand of daft pretension in passing street talk, and he lived the truth of farce's momentum. "My life beginning to run to a timetable no member of the royal family would tolerate," he writes during the last vacation in Tangier as the traffic plan for his liaisons with Moroccan boys assumes farcical complications. Orton's complaint about traditional farce was that it was "still based on the preconceptions of half a century ago, particularly the preconceptions about sex. But we must now accept that, for instance, people do have sexual relations outside marriage." Onstage and off it, Orton practiced an unbuttoned liberty.

But it was not just the rapacity of his farces that mirrored Orton's life. The joke at the heart of Orton's farce mayhem is that people state their needs but the other characters, in their spectacular self-absorption, don't listen. "Hum to yourself if you're sad," says the nurse in Funeral Games as she takes leave of the defrocked priest who is her patient. Orton's laughter invokes a world of no consolation, and in private Orton could give little to Halliwell. He was incensed on Halliwell's behalf at the "middleaged nonentity" slur. He continued to try to get Halliwell's collages exhibited. And in the last week of his life, while Halliwell sank into his final, fatal depression, he offered to take him to Leicester—a strange suggestion, since Halliwell had never visited Orton's family and would once again find himself an appendage. As the diaries show, nothing, not even Halliwell's veiled threats of violence, could make Orton attend properly to Halliwell's anguish. On March 9, Orton writes: "Kenneth said, 'You're turning into a real bully, do you know that? You'd better be careful. You'll get your deserts!' Went to sleep."

"You're a quite different person, you know, since you've had your success," Halliwell tells Orton in the diaries. And he was. He was more confident. Halliwell, as they'd written in The Boy Hairdresser, "preferred him wracked with hesitation, only at ease in a conspiratorial way." But now Orton's conspiracy for high jinks was with the public. It made him bolder and, to Halliwell, more threatening. "Arguing about a Polaroid camera," writes Orton on July 26. "Kenneth says it's a waste of money. I want one. Conspicuous wealth, I suppose." Orton had his own money now, and with it the freedom to do what he liked. Their old style of making do didn't fit his new life. Their room was no longer the haven it once had been. Orton was increasingly lured away into the world, where there were other people to listen to him and to laugh with him. "When I've taught you a little,'' says the Halliwell spokesman, Doktor von Pregnant, in Head to Toe, "you'll know as much as I do myself.'' That day had come. Halliwell had invented his perfect friend, only to watch his efforts win from the world an admiration he himself could never earn. In The Boy Hairdresser, they'd imagined Orton's "charm become sinister." And from Halliwell's point of view, it had. Orton sneered at Halliwell's attempts to stand out, he mocked Halliwell's sexual passivity, and—more hurtful—he disrespected Halliwell's "wifely" role:

Kenneth's nerves are on edge.... He had a row this morning. Trembling with rage. About my nastiness when I said, "Are you going to stand in front of the mirror all day?" He said, "I've been washing your fucking underpants! That's why I've been at the sink!" He shouted it out loudly and I said, "Please, don't let the whole neighbourhood know you're a queen." "You know I have hay fever and you deliberately get on my nerves," he said. "I'm going out today," I said. "I can't stand much more of it." "Go out then," he said. "I don't want you in here."

"The Daily Express telephoned me and said, 'Have you heard the news about Joe Orton?' " says Peter Willes, recalling how he learned of the playwright's death. "I thought Joe had been up to no good at the King's Cross cottages. My first thought was to ring Ken at the flat. I called. The police answered. That's when I learned Halliwell had killed him." Orton was a voluptuary of fiasco, and his death seemed a macabre echo of his plays. (Even Peggy Ramsay, terrified at having to identify the bodies, made a farce entrance, walking backward into their room.) Nobody, certainly not Orton, expected Halliwell capable of such an act of will. Orton had long ago begun to discount Halliwell's threats as yet another indication of his hectoring impotence. "When we get back to London, we're finished! This is the end!" Halliwell snarls at Orton in a bitter quarrel they have on June 27, a few days before leaving Tangier. The diary entry continues: "I had heard this so often. 'I wonder you didn't add "I'm going back to Mother" ' I said wearily. 'That's the kind of line that makes your plays ultimately worthless,' he said. It went on and on until I put out the light. He slammed the door and went to bed."

When he wasn't writing, Orton increasingly found ways to stay away from their flat. He was adamant when he told the comedian Kenneth Williams that he'd never forsake Halliwell, and Peter Willes concurs: "Kenneth thought he was losing Joe, but he never would have." In one sense, as the diaries show, Orton had already made an imaginative separation from Halliwell. Orton certainly couldn't continue to cohabit long in the atmosphere of cramped desperation and envy which Halliwell created around them. But Halliwell was the entire creative environment of Orton's adult life. Like so many literary figures with unhappy silent partners, Orton had persisted in the relationship both out of loyalty to his partner and because it was advantageous to his craft. Halliwell was not only Orton's editor and sounding board, he was his subject matter. Out of their melodramatic and tortured arguments about personal needs Orton got What the Butler Saw. He was prepared to buy Halliwell off with a house. He encouraged him to take up other people and other interests. The only way to change him, he knew, would be to change his situation. But Halliwell wanted only Orton and their world back. And that was lost.

"Events move in one direction and are cumulative," they wrote in The Boy Hairdresser. From their calendar in mid-August, it was clear in just what direction their destinies were going. On the day they died, a chauffeur was set to take Orton to Twickenham Film Studios to discuss Up Against It with Richard Lester. The following day Halliwell was scheduled to see a bona fide psychiatrist. When Dr. Ismay had called in the psychiatrist, Halliwell had told him he was "taking the matter far too seriously." But in the early hours of August 9, the prospect of Halliwell's leftover life drove him crazy. In murder, Halliwell was imitating their art. "Which is worse," asks Halliwell's alter ego in The Boy Hairdresser, before he attempts murder, "fruitless running or aimless drifting? Evil to look back on, nothing to look forward to, and pain in the present." Death made them equal again. In the anarchy of his farces, Orton had taken revenge for the fretfulness of his desires and disillusion. Now Halliwell did the same. What is left to the world is Orton's evergreen laughter, and the last testament of the fierce, sad kingdom of self from which it came: his diaries. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now