Sign In to Your Account

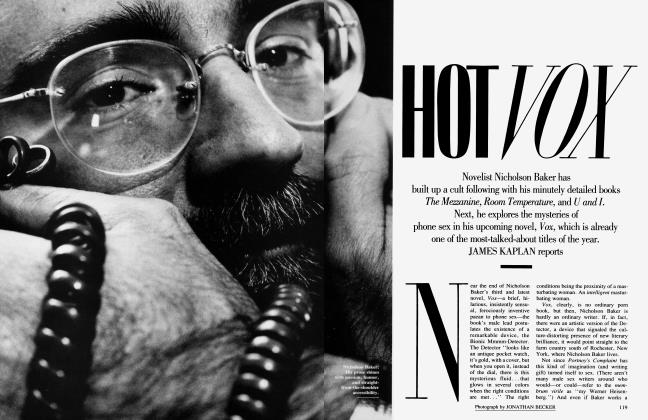

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE ART OF LIVING

If anyone should know how to live with paintings and sculpture and photographs, it's New York art dealer Robert Miller, who, writes STEVEN M. L. ARONSON, shares his apartment with one wife, three children, two poodles, an operatic parrot, and a rolling eclection of art

STEVEN M.L. ARONSON

Ji— t takes all of a twenty-room Manhattan duplex maisonette to house an art collection so profuse and wideranging it resists categorization. Rodin's The Thinker ponders on the piano in the living room. Louise Bourgeois's small Cat's Paw bids for attention on the mantel, while the top of her figurative Spring, on the floor nearby, rises to a bud. Lounging restively in a comer is Malvina Hoffman's bronze torso of Tony Sansone, the physical-culture nut who owned a Greenwich Village gym in the twenties.

On the walls, painterly worlds don't so much collide as meld: Andrew Wyeth's The Oil Lamp, a pre-war Marsden Hartley pageant, a translucent Janet Fish still life, a rare e. e. cummings self-portrait in open collar and flowing greatcoat. Everything here is wisely ordered, arranged by someone gifted with a visual imagination. Above a dark-blue Japanese pot that holds a living, blooming sunflower hangs the brilliant 1921 geometric abstraction The Sunflower, by the photographer Edward Steichen—the last painting he did before abandoning that medium. And flush with the living room's three floorto-ceiling windows, which look out on a quiet East Side park, Maxfield Parrish's painting of ghostly nymphs in a glade is like another window we are drawn to look through.

Elsewhere, in a long passageway, there's an ever changing wall of photographs, a kind of floating eclectic presentation: Man Ray today, Paul Outerbridge tomorrow, Berenice Abbott and Brassai yesterday. And everywhere, "dynasties dwindle to the tiny compass of the eye." Antique minor gods, ancient Near Eastern miniature bulls, Roman grave reliefs and architectural fragments, pre-Columbian figures from an island necropolis, swords and spear tips from tenthcentury-B.C. Luristan, and Chinese ritual wine vessels from the Sung dynasty all cohabit comfortably.

This dizzy diversity reflects the erudition, self-confidence, and independent spirit of gallery owner Robert Miller and his wife, Betsy. "It's a collective aesthetic,'' Miller explains, himself the very picture of an aesthete. "Somehow or other we ended up in a postmodernist tradition without ever having thought toward it. In that way there's a similarity between our collection at home and what we show in the gallery. We're not 'School of' collectors, and we're not a 'School of' gallery—no artist we have is like any other."

This is just a place where we live and are comfortable."

Indeed. In the ten years since it opened, the Robert Miller Gallery has been one of the most consistently exciting in town, exhibiting sculpture, painting, photography, and classical antiquities. In the plastic arts the gallery represents, among others, A1 Held, Alex Katz, Rodrigo Moynihan, Jedd Garet, Robert Graham, Louise Bourgeois, and the estates of Alice Neel and Lee Krasner; in photography, Jan Groover, Bruce Weber, Robert Mapplethorpe, Andy Warhol, and the estates of Diane Arbus and George Platt Lynes.

Last spring Miller relocated from Fifth Avenue to 7,500 square feet in the chock-full-o'-galleries Fuller Building, on the comer of Fifty-seventh Street and Madison Avenue, "at the very axis of the art world"—to the second-floor space just vacated by the jail-bound Andrew Crispo. A rumor circulated that Miller had had it exorcised to purge it of any vestigial sadomasochistic vibrations. "That place was a bad situation," he admits. The police had, in effect, initiated Miller's renovation by tearing out the interior walls of the gallery, even the marble slabs in the toilets. "Then we stripped it right down to the cement and the steel beams," he adds. "I didn't want to be responsible for anything that might turn up there."

While Robert Miller is responsible for the gallery, Betsy Miller takes charge at home. She's an artist in her own right—"an accomplished eeramicist," her husband offers, "and at one point she made all my suits and most of her own clothing." She's also an indefatigable cook. "Betsy thinks nothing of cooking for eighty—preparing forty pounds of broccoli or squash, steaming five eighteen-pound tilefish or four twenty-pound salmon..."

In the words of gallery artist Louise Bourgeois, Betsy Miller "reigns discreetly over'both the large collection and the large household." It's a hurly-burly combination of family and menagerie: three well-behaved children (Peter, sixteen; Sarah, fourteen; Christopher, thirteen), an apricot standard poodle named Charlie that's all simulated disobediences, a smaller poodle named Silver, three cats (Inky, Sapphire, Sergeant), an Amazon parrot named Wotan that "sings grand opera," and an untitled hermit crab that lives under a camellia bush in the living room. ("I found him in Hobe Sound, where we go every winter," says Robert Miller. "He's early Disney, with those Pop eyes.") Betsy Miller says, nonchalantly, "This is just a place where we live and are comfortable."

How comfortable are the children with the art? "It's a part of their life," she says. "Once in a blue moon they will take exception to a piece. We had something in the dining room, I can't remember what it was—they didn't want to have to look at it while they ate. 1 took it down because they have to live here, too." Betsy Miller is constantly replenishing and recirculating the art in the apartment. "There's a flow of material. Things go out on loan—to museums and exhibitions, to friends—and come back, and you rearrange. Or something has to go off to the gallery to be photographed. Or you see something and you want to bring it home and try it out."

Continued on page 148

Continued from page 89

"This is not a Park Avenue tracklight operation," Robert Miller adds. "We'd rather have the art lit by candlelight than megawatts, by sources that relate to the way we live in the spaces rather than by spotlights. So natural light or light from lamps is part of what determines where Betsy puts something."

There's nothing accidental in the way Betsy Miller puts things. In the entrance hall, for instance, two Matisse drawings are hung next to one of the masterpieces of the house, a second-century-A.D. Roman head of Apollo, on a pedestal. "I sort of like the relationship between the ruffles on the Matisse dress and the hair on the antiquity," she explains. On the opposite wall Robert Mapplethorpe's silver print of rock star Iggy Pop is perfectly at home under two screaming griffins perched atop Northern Italian Romanesque columns. "This Mapplethorpe is a favorite of mine—it has the poignance of a Goya to me," Robert Miller says. "Dad,'' pleads Peter Miller, who appears just as his father is finishing his lofty discourse on the photograph's Goyaesque qualities, "don't ever sell that—I love Iggy."

Also in the hall: a big A1 Held painting from his black-and-white series, and a haunted self-portrait by English painter Rodrigo Moynihan. "He's just finished a small personal private portrait of the queen," Robert Miller points out. "The official one he did of Mrs. Thatcher caused quite a stir. She didn't like the squint he gave her in it— thought it made her look too hardeyed." Part of the hall is a greenhouse where dahlias, foxgloves, and rubrum lilies grow. The Great Effort, by Pina, a student of Rodin's, takes a break on the floor at the foot of a Rodin.

Propped for the moment on a nearby table is David Hockney's sketch of Robert Miller, on which the artist has inscribed a line from Auden's "Letter to Lord Byron": "To me Art's subject is the human clay." Miller knows the verse by heart: " 'And landscape but a background to a torso; / All Cezanne's apples I would give away / For one small Goya or a Daumier.' What Auden is implying is that great art will have a human in it," he states. He gestures affectionately toward Hockney's drawing of Betsy—"made three days after she had our daughter in 1972. She looks exhausted."

In the dining room lurks Alice Neel's 1980 portrait of Robert Miller, in blue scarf and sepulchral pullover, looking grim. "I had to stand up for the portrait, and I was in pain because of a back injury. Also, it was summer and she had me wearing a black sweater and a scarf. Anyway, people don't like facing their portraits," he explains, adding, "I'm convinced Alice Neel is one of the most significant portraitists in all our American history. The National Portrait Gallery recently purchased two of her portraits from us, a large one of Linus Pauling and one of herself that she did just before she died—can you imagine the staid National Portrait Gallery buying a painting of a nude octogenarian, life-size yet! Of course, she's famous for her nudes. She said to Betsy, 'Oh come on, I want to paint you, take your clothes off!' "

Betsy Miller, however, sits fully clothed in her Neel portrait. "It looks watchful,'' she says, facing her likeness and liking it. "I look strong and I am strong. People say, 'You don't look pretty.' I don't look pretty—it's not important to me to look pretty. I'd rather look strong than pretty. When Robert Mapplethorpe took my portrait, the same quality came through.'' Her face suddenly wears a look of purpose. "Georgia O'Keeffe once said to me that she could never like anybody who wasn't strong, whose strength she couldn't respect—that was one requirement of friendship. I gave her her ninetieth-birthday party in this apartment. One of our cats, Sergeant, who's particularly large, would always sit on her lap and she would always say, 'This is a very heavy cat.' It's funny how she never failed to comment on the weight of that fat cat. She was a good friend of my sister's mother-inlaw, the next-to-last Mrs. J. Seward Johnson. Georgia used to go to New Jersey to see her all the time when the Johnsons lived in Oldwick."

The Millers own several ravishing O'Keeffes. On the mantel in the living room is a double-sided drawing: one side shows a hibiscus blossom; the other, a landscape that evokes the blackplace series of O'Keeffe's paintings. Robert Miller recalls, "Georgia gave it to me at the conclusion of a visit I made to her house near Ghost Ranch, where we stayed alone for several days and took walks in the desert and talked of Stieglitz's poor digestion." In the music room an O'Keeffe poppy is strewn on a table like a blossom, and over the fireplace hangs her View of the River— "one of her wonderful paintings that mix abstraction and a kind of pictorial reality. It's the river that flows near Ghost Ranch. Once I was coming in by helicopter with Calvin Klein—he's a client of the gallery and a big O'Keeffe enthusiast—and he said he wanted to buy her house, but when we got closer and he saw the mud huts next to it he changed his mind. She stood in the sand waiting to greet us— wearing a Calvin Klein cardigan. Standing there in that desert in his sweater she looked like a time-lapsed photograph of one of his models.

"You know the artist, you know where the picture was painted— there's a relationship you have. This is genuine collecting as opposed to what's-hot-at-the-moment. For instance, Lee Krasner's Noon that we have in our living room—one of her great, early 'all-over' paintings—relates to a beach in East Hampton that Lee used to go to called Louse Point, and if you look down at the shells and stones at noon, there's the whole surface of the picture. It's a completely abstract painting, but it draws its essence out of life."

Robert Miller himself has the ability, crucial to an impresario of art, to detect and magnify the essence of a work, then reify his discovery for others. Some of us introduce people to people, Robert Miller introduces people to objects. As Bruce Weber, whose show of romantic pastel-toned Rio photographs opened the fall season at the gallery, recounts, with a touch of awe: "Bob called me up one day and said, 'Bruce, I have a sculpture here—nobody likes it, but I really want you to see it.' So I went up to the gallery and there in this all-white room was this faded white statue of a young man, American Youth, by some virtually unknown sculptor, done in the forties—all broken, without arms, but it had this really beautiful face, and a leanness to it—it was graceful and childlike. So I photographed it, and even before I saw my contact sheets I knew it was going to be one of my favorite pictures I've ever done. And when the contact sheets came back there was this strange separation—you almost couldn't tell where the white wall ended and the white figure began, and then suddenly the face just bounced out of the contact sheet, and the shape of the body—the destroyed quality of it loomed out and made you want to touch it. It's a great talent Bob has— he knew how to make me see something that was so beautiful in something that was so destroyed. He almost wills you to see things in a unique way, and he can certainly make you fall in love with them." □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now