Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

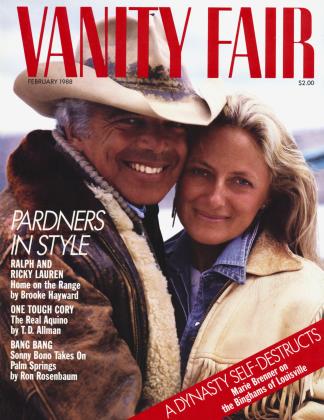

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowONE TOUGH CORY

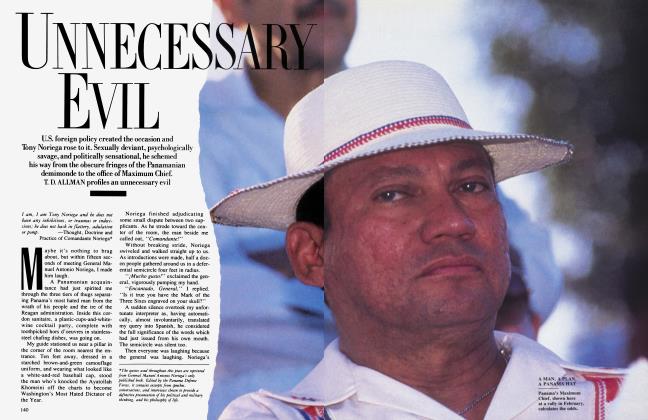

Forget about the mealymouthed housewife. Corazon Aquino was always a woman of steel. T. D. ALLMAN went to Manila to interview the Philippine president and, after talking to her friends and her enemies, came back with a surprisingly revisionist view

Cory Aquino cures asthma by crushing coups. "I used to suffer from it terribly before I became president," she told U.S. ambassador Nicholas Platt after mutinous troops tried to kill her last August 28. "But ever since, I've been breathing easy. It must be the adrenaline."

She needed adrenaline that night. Rebel troops had advanced to within five hundred meters of her residence near the Malacanang presidential palace in Manila. Outside, she could hear the gunfire coming closer and closer.

They had wounded her only son; if they got much closer, the odds were she'd be dead in an hour. "Blood was all over the place," one presidential aide later said. "When I finally reached the palace I had to wipe it off my shoes."

Inside, President Aquino, still wearing her nightgown, stood in the darkness, telephone in hand, trying to rally members of her government. "I called my minister of defense, but I couldn't get through," she later said. "I called the chief of staff, but couldn't get through. I called my executive secretary, but couldn't get through.

"So I called Him." She pointed skyward. "I can always get through to Him. "

It was one of those moments when President Aquino seemed to be exactly what her enemies keep hoping she is—a naive, passive housewife whose first response, even to artillery fire, is to say the Rosary. But by the time loyal members of her staff had gathered around her, quite another woman was in charge. During a lull in the fighting, the president quickly changed into a green dress with a white embroidered bodice, fixed her hair, and applied a little lipstick and eye shadow. She was "very cool and very calm," one person who saw her that morning told me. "You'd never have guessed she'd just looked death in the face."

With the initial attack repulsed, there was talk of negotiating with the rebels, who had occupied part of Camp Aguinaldo, headquarters of the Philippine military. The president's orders were unequivocal: "No negotiations. No terms. Hit them hard, and hit them now." Mrs. Aquino also rejected pleas she move to a safer place. "Marcos made two mistakes," she told the commander of the Presidential Security Group. "He left Malacanang, and he did not immediately attack the rebels. I will not make the same mistakes. We shall defeat and punish these traitors."

By early afternoon, for the first time in history, Philippine troops were killing other Philippine troops in the defense of a civilian president. Rejecting calls to join the rebels, they instead obeyed their female commander in chief.

Soon more than a thousand rebel troops had either surrendered or been captured, and were being sent to navy ships in Manila Bay to await court-martial. The leader of the failed coup, Colonel Gregorio "Gringo" Honasan, fled into hiding. Thanks to President Aquino's determination to crush the rebellion "with maximum force," the Philippines' new democracy had passed a crucial, if tragic, test.

Later, in her office, when the president was discussing the mopping-up operations with members of her staff, an assistant asked her, "Mrs. President, why do they always think you're weak?"

Corazon Aquino shrugged.

T. D. ALLMAN

"They underestimate me," she said. "Then I smash them."

Since August 1983, when her husband, Benigno Aquino Jr. (whom Filipinos almost always call by his nickname, Ninoy), was murdered, many different images of Corazon Aquino have filled the world's newspapers, magazines, and television screens. First there was the almost unnaturally calm widow, tearlessly condemning the Marcos dictatorship on Nightline within hours of her husband's death. Next came the woman of unbounded determination who, while both Marcos and his opponents scarcely noticed it, transformed herself from the symbol of the struggle for democracy in the Philippines into its supreme leader. Then, in February 1986, when she defeated Marcos in presidential elections, and the Philippines' euphoric, peaceful "People Power" revolution swept her into office, "the Cory who could do no wrong" appeared—as the president herself, with both humor and exasperation, describes it. Only thirteen months ago, in its Woman of the Year paean to her, Time fixed this image of Aquino in print—the "soft-spoken housewife" with no political experience whom "a fairy-tale revolution" had catapulted into power.

"That view of me certainly didn't last very long, did it?" Aquino remarked recently. "To read some of the reports, you'd think Fd done nothing at all."

In some news reports, it has been a truly Icarian descent. Time itself now chides President Aquino for her "weakness." It also criticizes her "almost blind faith [in] democratic institutions"—while allotting her "some credit for this year's five percent rate of economic growth," noting her "toughsounding speeches" and frontline visits to guerrilla war zones, and admitting that most Filipinos "adore" her. In a recent New York Times Magazine story, Manila bureau chief Seth Mydans grudgingly acknowledged that Mrs. Aquino has restored "these freedoms and institutions that were her priorities in the first portion of her presidency." Seeing no apparent contradiction, he characterizes her in the same piece as a president "who appears to recoil from using power. ' '

On the marathon flight from New York to Manila, I encountered, in the magazine rack, a "weak," "beleaguered," and "irresolute" Aquino I'd never met in person.

According to Newsweek, President Aquino was "feckless," the synonyms for which are "spiritless; weak; worthless"—epithets even her bitterest enemies never used in my one hundred interviews with people who knew the president personally. While she dithered in her palace, the story suggested, a variety of "strongmen" were preparing to replace her with a can-do, macho junta, on which, if they were generous, they might even permit her to sit as a pliant figurehead.

THE LAST DAYS OF AQUINO? the Newsweek headline asked, CAN CORY BE SAVED?Time chimed in a few weeks later. The New Yorker expressed grave doubts. At best, she would "simply muddle through the next four and a half years." At worst, the Philippines would find itself "ineluctably heading toward disaster." Which would it be?

The Atlantic provided the answer. Not only Aquino but the whole Filipino people were too feckless to make democracy work, it reported, because they had a "damaged culture," and the Philippines was "a nation without much national pride." Instead of worrying about Aquino's being ousted in a coup, James Fallows concluded, Americans ought to be worrying about what to do if she weren't overthrown—"and the culture doesn't change, and everything gets worse."

So when I got to Manila, I asked President Aquino, "What would it take to get you either to resign or to surrender your presidential power to a junta?"

Mrs. Aquino was seated behind a mahogany desk in her office, a highceilinged, wood-paneled room on the upper floor of the Malacafiang guesthouse, where Imelda Marcos once entertained friends like George Hamilton and Gina Lollobrigida. Three presidential security guards—wearing sporty gray leisure suits tailored to conceal their weapons—were on the balcony outside. But we were alone in the room except for the president's daughter Maria Elena, who acts as her mother's private secretary. She sat, almost out of earshot, at a small desk some twenty feet away.

Mrs. Aquino was wearing one of those demure, slightly frilly dresses she's made her trademark—it would have looked dowdy in these surroundings when Imelda Marcos still had the run of the place. She looked like the president of a P.T.A. committee as she smiled cheerfully and answered my question.

"Well, I guess they'd have to kill me," she said.

Mrs. Aquino's insistence on doing things exactly the way she wants, when she wants, extends to what is written, not just done, in her name. When Random House won the rights to her memoirs, there was the natural assumption that the project would be handled as memoirs of prominent public figures often are. A writer was dispatched to Manila. It was expected that Mrs. Aquino would merely dot the i's and cross the t's on the manuscript this person wrote.

But Mrs. Aquino soon sent her amanuensis packing. "This stuff is too sweet," she said. "I'm going to write my own story my own way."

"We women," President Aquino said later, "know we have our own timing and our own ways."

Copy has already started flowing to New York, and her editor, Jason Epstein, is impressed. "She's a very strong person with a very powerful sense of herself," he told me. "And this comes through very clearly in her writing."

He added, "She would no more let someone else write her own memoirs than she would let someone else run her own government."

Cory Aquino would never have become president if all those cliches about her were true.

"You underestimate her at your peril," says former defense minister Juan Ponce Enrile. Enrile has reason to know. Having summarily dismissed him from office, Mrs. Aquino crushed him in national elections last year.

That tearless composure Mrs. Aquino displayed following her husband's murder, for instance, no doubt did in part derive from her deep Catholic faith. But what even some close relatives to this day find puzzling is that even in private Corazon Aquino never shed a tear for her husband either during his funeral or thereafter.

What intimates did know long before Ninoy's death was that theirs was no storybook marriage.

"My husband, well, he was a male chauvinist," Mrs. Aquino told Gail Sheehy after he was killed. Before, and by some accounts even after, Marcos imprisoned him in 1972, Ninoy Aquino was unfaithful to his wife, which is considered normal in Philippine society. While silent on that issue, President Aquino is frank about their other marriage problems.

"From the first day that Ninoy entered politics," she wrote in an article published after her inauguration, "I kissed all hope of a private life goodbye. It became clear to me and to my children, as the years went by that family would have to come second to the demands of his political career."

According to the president, Ninoy Aquino was a distant father and a selfindulgent husband. During labor with her first child, Mrs. Aquino recalled, "Ninoy [was] at a loss on what to do," and fled the delivery room. "He was always afraid to carry our babies during their first months," she added. "He could be helpful only as far as removing wet diapers. But when it was messier than that, he would call me or the midwife, shouting in a loud voice that he couldn't handle it."

He also refused to discipline their children. "I think it was because his politics took him so much away that ... we, no, he, had decided on a division of labor. He would be the indulgent parent and I would be the disciplinarian." Only once did he chastise one of his children: he spanked their three-yearold daughter, Maria Elena, because she didn't want to leave her mother to spend time with him after a long separation. To make amends, he instructed his houseboy to buy the child some chewing gum.

Nearly eight years of imprisonment actually marked an improvement in such a marriage because, for the first time, as Mrs. Aquino explains it,

we had no distractions from each other during those [prison] visits and we really opened up to each other. Needless to say, we were both on our best behavior with each other. We wanted no unpleasantness to mar those hours between 1:00 p.m. of Saturday and 10:00 a.m. of Sunday. I cannot remember an occasion where I was alone with Ninoy for twenty-one uninterrupted hours before his imprisonment!

Marcos's efforts to destroy Ninoy psychologically were extended to his wife. On one occasion, a Marcos agent called on Cory and handed her an envelope. "It contained graphic documentation of his relations with other women," a source told me. "She handed the envelope back to him," this person said. "She told him these matters concerned her and her husband only. She showed no anger, no shame; she displayed no emotion whatsoever."

The periods of being held naked in solitary confinement had a different effect on Ninoy Aquino from what Marcos intended. For the first time in his life, he became introspective, spiritual, and, as his return to the Philippines in August 1983 ultimately demonstrated, capable of a heroism that made history, changed the lives of millions of Filipinos, and deeply touched his own wife. "All his previous political achievements were as nothing compared to the victory he had won there over himself, ' ' she later said. "Some women love their husbands in spite of their faults," a family friend told me. "Cory loved the whole Ninoy. Helping him triumph over his adversities was the great triumph of her life. I think it still means more to her than the presidency."

Yet even after he was released from prison in 1980, while they were living in exile in Boston, they still had difficulties, as Mrs. Aquino puts it, "learning to readjust to each other. I did not think that this would be necessary, but I guess, having lived apart for almost eight years, seeing each other only on those precious visits in prison, we had forgotten how different real family life is.

She added, "I think, when that chance came, that he did try his best during the last three years of his life."

When I asked a lifelong friend of the Aquinos' to discuss the president's feelings about the loss of her husband, this normally uninhibited woman refused absolutely. "I love Cory too much to lose her," she answered. But later, in a different context, she said, "I don't think a male foreigner could ever possibly understand what it is like to be a Filipina wife. Loss of your husband is the ultimate tragedy. But it's also a form of liberation."

Friends and family, however, are quite frank about another aspect of the president's character. Corazon Aquino had what one of her brothers calls "an unnerving and very un-Filipino" capacity to separate herself from her emotions long before she started ordering artillery attacks on rebel troops.

David Puttnam, who is preparing to produce a film about Ninoy Aquino and has spent much time with the president, has grown to respect her deeply in the course of their meetings. She is "absolutely fatalistic about her situation in life," he says. Allen Weinstein, of the Center for Democracy in Washington, feels that her religiousness, which runs very deep, provides an inexhaustible reservoir of composure and strength.

Whatever the reasons, all who know her agree on one thing. "Cory is one who will not cry," her mother-in-law, Dona Aurora Aquino, told me. Yet I heard of two occasions when she did cry. Both revealed something about the political strengths and personal values this woman has brought to the presidency.

Her brother-in-law Ernesto Lichauco described the first incident. "It was the morning after one of her visits to Ninoy's prison cell," he recalled, "and as she narrated what had happened, her hands wavered uncontrollably. She was in tears."

As usual, the two had spent hours in his cell talking. But, for once, this consummate politician did not talk to his wife about politics. "Ninoy kept saying he hadn't been able to do enough for his family," Cory said after the visit. "He kept saying he was sorry he hadn't done enough for his family."

When Cory Aquino waved good-bye to her husband, he did not wave back. "His hands were clasped behind his back," she told relatives. "He'd lost so much weight he had to hold his pants up, but he was trying to disguise it. He didn't want us to worry." The tears came only after she had left.

Emanuel "Noel" Soriano, President Aquino's nationalsecurity adviser and head of her Crisis Management Committee, described the other time she became very emotional. In 1984, he and others had formed a group, called the Conveners, to coordinate opposition to Marcos. The members of the group said no when Cory Aquino wanted to attend a meeting of UNIDO, the party of Salvador Laurel, her chief rival in the prospective presidential race to unseat Marcos.

"Tears welled up in her eyes," Soriano remembered. "That's the last time I'll let you tell me what to do," she told the group. "It was," added Soriano. "After that, nobody, but nobody, tried to impose his will on her."

The "housewife" take on Aquino has never been right.

Cory Aquino was bom Maria Corazon Sumulong Cojuangco —the Sumulongs and Cojuangcos being two of the most influential families in the entire country. The daughter of a very rich family in a very poor country, she never had to make a bed until she was sent to Ravenhill Academy, an exclusive Catholic girls' school in Philadelphia. When she married Ninoy Aquino, she had to take cooking lessons from his sister Maur Lichauco. Even then, this was no matter of preparing rice and kare-kare. Her specialties were gourmet productions, pate and Peking duck.

At the College of Mount St. Vincent in New York, she was an ambitious student, majoring in two subjects. One was French (which she still enjoys speaking). Her other major was an even more unlikely choice for a Filipina back then—mathematics, a "cold" science which, she once explained, interested her because "I wanted to be different." Before her marriage, she also studied law in Manila—in her words, "as a discipline."

President Aquino's elite origins have certainly not gone unreported. To focus on all the maids, chefs, chauffeurs, and French lessons, however, is to miss the main point. Growing up in typical oligarchic fashion in the Philippines—if you learn the right lessons from it—can provide oddly appropriate human training for being a president. Armies of relatives, retainers, and favor seekers are constantly entering and receding from your presence. Everyone wants something. On the Cojuangco family's immense Hacienda Luisita, as much as in Malacanang Palace, there was no such thing as private action divorced from consequences for others.

"Mrs* President, why do they always think you're weak?" Corazon Aquino shrugged# "They underestimate me# Then I smash them*"

The notion that President Aquino took office as a political innocent is the most absurd one of them all. For more than thirty years before becoming president, she closely observed and participated in high-stakes, hardball politics. Her husband was, next only to Marcos, the most prominent and controversial politician in the country. Her own Cojuangco family was involved in fierce political struggles, notably against Eduardo Cojuangco, the president's own first cousin, and one of Marcos's most corrupt cronies.

"Her husband's imprisonment," as the president's former executive secretary, Joker Arroyo, put it, "was a seven-year graduate course in national leadership for Cory, because she needed all the same skills that she needed later to defeat Marcos.

"She had to have a photographic memory," he explained, "because nothing could be left on paper for the Marcos secret police to find. She had to be an instant judge of character—to be able to tell if someone was a friend or a spy. She had to make thousands of intuitive decisions involving life and, quite possibly, death. She had to learn to live with a total lack of privacy. [Her conjugal visits with her husband were taperecorded, and quite possibly photographed.] She had to know when to act—and when not to act. She had to find within herself tremendous reservoirs of moral and physical courage. She also had to learn," he concluded, "how to dissemble."

Finally, during the twenty-nine months between her husband's death and her own election to the presidency, she led a vast popular movement that toppled a dictator whom for twenty years no male opponent had been able to beat.

"We're different from ordinary people," President Aquino remarked to an aide in private, following a meeting with Singapore's autocratic prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew. "We have power and know how to use it." But in public she consistently disguises this side of herself. Just around the time she had that meeting with Lee Kuan Yew, a European journalist asked her to explain her rise to power: "I was merely thrust into the presidency by the sweep of events following the assassination of my husband, Benigno," she replied, in what can only be described as a deliberate and gross misrepresentation of the facts.

Mrs. Aquino's astute exploitation of her housewife persona caused Marcos to fatally underestimate her. But the way she has bested even allies—like her husband's lifelong friend Salvador Laurel—provides a more revealing glimpse of how she operates.

Laurel had been the equivalent of best man at the Aquinos' wedding in 1954. In the next two decades he would become one of the Philippines' most prominent politicians. Laurel's UNIDO party had nominated him to run against Marcos well before Mrs. Aquino became a formal candidate for president.

But that wasn't the way things turned out. In a series of face-to-face confrontations, Aquino forced Laurel to abandon his presidential ambitions and run as her vice-presidential candidate instead. It was a test of wills that quite probably decided the fate of the country. Had they run against each other, the opposition vote would have been divided and Marcos possibly could have won. Yet Aquino adamantly refused, under any circumstances, to abandon her own candidacy. Laurel, she insisted, was the one who must give way, and, in the face of her absolute refusal to compromise, he did.

In Manila I asked one of President Aquino's most trusted advisers why she had been so utterly determined that she, and no one else, must succeed Marcos as president.

"First of all," he said, "after Ninoy's death, she got to know all the main opposition leaders really well. And she decided, 'I'll make a better president than any of these men.' Second, she realized if she wasn't the candidate, it would be Laurel, and she had a very low opinion of him."

If this indeed was her opinion, Cory Aquino disguised it well. "I'll just be an interim figure," Laurel says she assured him. "I'll probably resign after a year or two, and you will succeed me. In any case," she is said to have promised, "you'll run the government. After all, I'm just a housewife. I know nothing about such things."

When I asked her, President Aquino categorically denied she'd made those specific statements. But when it came to the "housewife" line, she equivocated: "I said this to everybody at the beginning."

What no one denies is that Laurel was told he would be made prime minister. Indeed, he was named to the post. But just sixteen days later, President Aquino abolished it and concentrated all executive power in her own office. The man whom Corazon Aquino had encouraged to imagine he would be running the government suddenly found himself, as Laurel describes it, a "spare tire."

Following suppression of last August's coup attempt, President Aquino once again was reshuffling her Cabinet—dismissing person after person who'd once imagined he, not she, would be in charge. Seeing the handwriting on the wall, Laurel played his last card. Before she could fire him, he tendered his "irrevocable" resignation from her Cabinet. (He retains the office of vice president.) At a final meeting, Aquino offered Laurel nothing—"absolutely nothing," as a member of the president's family told me. "He was no longer useful to her. She was glad to get rid of him."

Where did Corazon Aquino learn to disguise her use of power so effectively? Like so much else, she seems to have learned the value of political dissembling as a result of her relationship with her husband.

"My husband. . . never wanted it said that I was influencing him in anything,'' Aquino once remarked.

"I have no political ambitions," Corazon Aquino informed the Conveners Group when it began canvassing for candidates to run against Marcos.

"Cory, what's this in the papers?" her mother-in-law, Dona Aurora, asked. "Have you really said you'll run?" She, like virtually all Aquino's friends and relations, learned of Cory's decision to run for president from press reports.

When Mrs. Aquino filed her declaration of candidacy with the election commission, she listed her occupation as "Housewife."

This combination of cold resolve, noblesse oblige, political savvy, and canny exploitation of what others consider her feminine weakness helps explain why in just two years Corazon Aquino has not only toppled Marcos but put down five coup attempts and won landslide victories in three national elections. It also explains why the political landscape of the Philippines is littered with fallen strongmen.

As many of these men freely concede, their problem with President Aquino isn't her "weakness." It's that, to the consternation of those who once imagined they could dominate her, she's turned out to be such a strongwilled president. In fact, most of the criticism of Mrs. Aquino you hear derives from the fact that there sits in the president's office a fifty-five-year-old widowed society matron with five children (including a teenage daughter who embarrasses her mother by wanting to be a movie star); and for reasons her enemies still can't quite fathom, every day this woman conducts her business on the premise that she, and she alone, is her country's duly-constituted chief of state. She doesn't care if you oppose her, so long as you do it within the framework of the constitution. She doesn't even care if you disobey her, though she'll fire you if you do. She certainly doesn't care if you hate her, though if you show the slightest disloyalty to her personally, or if you become an embarrassment to the office she holds, she's quite capable of cutting you dead, even if you are a close relative or friend.

(Continued on page 136)

(Continued from page 115)

But if you once violate the democratic rules of the game she's established, she'll smash you—either right now or later on, when she decides the moment is ripe. And what drives some people up the wall is that, almost always, she does this in such a polite, well-bred, very feminine way.

"I see them walk into this office and see them walk out. What enrages some of these guys," says presidential consultant Teodoro "Teddy Boy" Locsin, "is that she simply doesn't respond to crisis the way they want her to respond. You can try to threaten and intimidate her, like Enrile did. You can fire off guns, like Honasan did. You can even be chivalrous and try to charm her, like Laurel did. But if she doesn't want to do what you want her to do, when you're finished she says, 'No. You don't seem to understand. I am the president.'

I saw what Locsin meant when I visited the president's office. We were discussing the possibility of another coup. What if next time, I asked Cory Aquino, they actually made it into the palace? Would she still stand and fight? Any male in her position, to say nothing of Margaret Thatcher, no doubt would have chosen this as the appropriate moment to display the jutting jaw, the firm fist slammed down on the table.

The reply was nice, ladylike—and utterly unyielding. "I believe 1 have a commitment to the Filipino people to stick it out, no matter what. And I've said, time and time again, that I am prepared to offer my life, if necessary, for the country, and"—the president paused, as if sensing her visitor, having come all this way, might appreciate a little more drama—"I have not changed from that position."

Would she share her presidential powers with people like Laurel and Enrile?

"No, because when we had the plebiscite in the matter of the constitution, whether it will be ratified or not, the people overwhelmingly ratified the constitution. ... So all of these other proposals are just meant to get some people into power before [my term expires in] 1992. I keep saying that all those who have presidential ambitions should wait until 1992, because that has been mandated under the constitution."

Would she, under any circumstances, resign the presidency?

"No" was her succinct response.

I decided to ask President Aquino something more tricky. Marcos had used his emergency powers to create a dictatorship. As a result, martial law has such a bad name in the Philippines that it would be extremely difficult to impose it, even if a real national emergency did arise. Would she, under any circumstances, impose martial law?

"If the situation warranted it," she answered without hesitation, "of course I would. If it were my belief there were no other remedy, certainly."

Corazon Aquino is a lot less exuberant than members of her husband's family. In fact, in comparison with the Aquinos, the Cojuangcos are supposed to be a dour lot. But when I posed what seemed to me a very somber question, it brought out a streak of good humor that lasted most of the rest of the interview.

"Mrs. President," I asked, "will you remember August 28 as the worst day of your presidency ?"

"Well, I certainly hope so!" she exclaimed, and broke into full laughter. "I do hope there won't be any worse days than that."

Ever since I'd seen photos of her during the coup, in that demure green dress, I told her. I'd "had this image of you, while these artillery shells are exploding around you, and in the darkness, of you having to put on your lipstick and makeup—"

"Well, yes!" she interjected, before I could finish. "That's the difference between a female president and a male president. But I couldn't do much about my hair. In fact, some of the girls who work in the beauty parlor I go to were saying, 'Oh, ma'am, we wish so much that we at least could have fixed your hair that day.' I told them that was the least of my worries."

"So you actually had to take time while the shooting—"

"Oh, no, no. This was after. While the shooting was going on I was not putting any makeup on."

I couldn't quite believe it. Here I was, laughing with Cory Aquino about a coup d'etat.

"You have a curious personality," I heard myself saying.

"That's the first time I've heard it described that way," the president responded. "O.K. What's curious about it?" she asked, evidently ready for a psychological critique.

Instead I asked what it was like to know that, outside that window to the right of her desk, in the vast tropical city beyond, there were men in safe houses, with guns, who'd kill her if they could.

"Well, even Jesus Christ had enemies, and who am I to think that I am somebody so great that I will not have enemies?" she replied pleasantly—as if to say: Who am / to complain, after all He went through?

"I think," the president continued, "I would not like to be a person with no enemies, because then it would make me appear as someone so bland, or so ineffectual, that everybody would just ignore me."

"Over and over again, you have to confront these men," I observed. "Isn't there a certain amount of male chauvinism that you have to fight, as well as military mutinies and the Communist insurgency? Isn't that what the 'weakness' charges are basically about?"

President Aquino seemed to find answering this question nearly as amusing as answering questions about the coup.

"Yes, I think so," she said. Then, laughing: "But, for those who know me, they know well enough that I am not about to let myself be pushed around by anybody."

More laughter, relaxed laughter—not the kind that anxiety, fear, and stress produce. She seemed to find it genuinely funny that a bunch of guys with guns imagined they could push her around just because she was a woman.

Corazon Aquino drew up to a halt only when I asked what would happen to the Philippines if they did kill her.

"If I were killed ?" After a long pause, she said, "I don't really know what would happen after that. I suppose there would be more divisions. I hate to even think of the scenario, but the great majority of Filipino people just want peace. In fact, that's one of my shortcomings: I abhor violence, but my enemies think nothing of resorting to violence, so I suppose that is my disadvantage."

"Yet you have to kill people every day now, don't you?"

"But it is only to prevent greater violence—"

"I understand that. But as a profoundly nonviolent person, how do you deal with that?"

"Well, because I have a greater obligation, because we have pledged to protect and defend the people, so we are not going to allow a few to just kill, and not do anything about it."

At the time, I thought I'd got her— forced her to stare into the face of her own mortality. But as I listened to the tape, I realized I was wrong. You could tell from her tone of voice: she'd just been thinking through the question. What would happen to the Philippines if she were killed? This woman who was not embarrassed to compare herself to Jesus Christ was not so self-centered as to suppose that her fate, for all its congruences, was identical to the fate of the entire nation.

They'd have to kill her to get her out of this office, she guessed. But even if they did kill her, even though the scenario would be terrible, even though there would be terrible divisions, the Filipinos would remain a peaceful people. They would just want peace. If these were the symptoms of a "damaged culture,'' it seemed Corazon Aquino was willing to live, and die, with that fact.

Recently, as she discussed with some staff members and friends the objectives she'd set for herself during her first two years as president, Aquino reflected, "Marcos proclaimed solutions to problems like land reform and Communist insurgency every day for twenty years. And where did that get us? Up to our nostrils in debt, and to the brink of civil war. You can't dictate progress to 58 million people, so I decided to unleash a process of democratic change which the whole Filipino people, not just I, would direct. But first we had to get the structure of democratic process in place.''

The foundation of that structure was a new national constitution which was both written and presented to the voters in record time in February 1987. On the eve of the plebiscite, both Mrs. Aquino's opponents and many foreign observers predicted she would either barely scrape by or lose. In any case, they said, this was the beginning of the end for the housewife president. Instead, voters surged to the polls and approved the "Cory Constitution'' by a massive majority. For her adversaries, this victory was particularly galling, and not just because, as she puts it, "it was also a referendum on me, and what I was trying to do.'' For with the constitution in place, it meant that even if, someday, her enemies did replace her, they would have to govern according to the democratic rules she had established.

When national elections were held in May last year, again there were dire predictions of defeat. But Mrs. Aquino's candidates won 22 out of 24 seats in the Senate, and approximately 150 out of 200 seats in the House of Representatives.

Following approval of the constitution, and election of the Congress, Aquino implemented the last phase of her initial blueprint for the Philippines. In her own words. "I stripped myself of the vast, supreme powers I held in my single hand, and became a constitutional chief of state."

Even though an independent judiciary and legislature now exist, Aquino's powers nonetheless remain at least as great as those of a U.S. president. And while her critics sometimes accuse her of being a crypto-Communist, she's actually used those powers to "get government off our backs" to an extent Ronald Reagan has never dared.

In two years, Mrs. Aquino has dismantled the entire corrupt, inefficient system of state intervention in the economy Marcos and his "crony capitalists" built up. (Marcos had run up a foreign debt of more than $28 billion.)

"Many major reforms have been undertaken," says a World Bank official in Washington. "The economy is responding. If the economic-reform program stays on track, the Philippines could emerge as a major East Asian exporter."

Nonetheless, the fact that the Philippines has made one of the quickest and most successful transitions from dictatorship to democracy in history seldom surfaces in the foreboding reports from Manila. There have been few headlines to the effect that the national currency is stable, inflation is under control, the gross national product is growing, and unemployment, if only marginally, is down. These factors nonetheless do help resolve another mystery. If she really is so feckless, why does President Aquino remain so popular?

If you ride the jeepneys into the average working-class neighborhoods, not just the worst slums of Manila (where Aquino is actually more popular than she is in the rich neighborhoods)—and if you talk to people in rural areas all over the country, not just in those newsmaking provinces where there are critical security and economic problems—this mystery simply disappears.

Before she became president, such average Filipinos lived under a corrupt and repressive dictatorship and were getting poorer every day. Today they enjoy basic democratic liberties—not mere abstractions like habeas corpus, but the freedom to wave a political banner, complain to a government official, and vote. (Of all their national fiestas, elections may be the ones Filipinos enjoy the most.) And, at the absolute worst, they're not getting poorer anymore.

These may not be Utopian achievements. But the systematic unfolding of the Aquino blueprint did create a real crisis—for those who initially supposed that they, not the "housewife," would run the country.

In last year's Senate elections, for example, both Enrile and Marcos supporters, along with Filipino leftists, all ran slates of candidates against Aquino's ticket. Not a single candidate of either the extreme right or left came close to winning. Twenty-two of Enrile's candidates were defeated, even though his side massively outspent Aquino's. Enrile himself finished a humiliating twenty-third in a field of twenty-four.

If you can't win by the rules, of course, you can always try to win by breaking them. Even before the constitution was approved, ominous troop movements occurred. Strong supporters of Aquino were assassinated. A confederation of increasingly desperate men attempted to force her to yield power before the new constitution and free elections cut them completely out of the game.

As this struggle unfolded, the strongmen learned something about Corazon Aquino. The housewife could play hardball, too. Did they move tanks? She sent up helicopter gunships. Were they plotting with certain officers in the armed forces? She built her own military-power network—in part by winning over a number of generals' wives. Uncounted millions of pesos, and perhaps dollars, changed hands, but not all of it came from the slush funds of Aquino's opponents. The president's brother Jose "Peping" Cojuangco in those crucial months traveled all over the country winning, and, according to sources in the Philippines, sometimes buying, the loyalty of key political and military figures, some of them just as much a part of the old Marcos system as Enrile had ever been.

This war of nerves went on for months, and so the pattern repeated itself. People asked: Why was the president so weak? Was she going to let Enrile walk all over her forever?

Then, just before dawn on the morning of November 23, 1986, to use her own terminology, Mrs. Aquino smashed Enrile.

When she issued a sudden, pre-dawn summons for them to assemble immediately at Malacahang Palace, members of the Cabinet were tense, thinking there had been a coup. But the president was utterly at ease as she announced Enrile's dismissal, and for excellent reason.

"The amazing thing about her timing," Teddy Boy Locsin told me, "was that this time there had been no coup attempt. The wire services and American correspondents were sending out all these reports about hostile troop movements, but they were our troop movements. I'd been up in a helicopter all night, checking. I knew. Contrary to everyone's advice, she decided to strike at the exact moment when Enrile posed no threat." Months earlier Aquino had laid out her strategy: "I'll get rid of him sometime when it won't create a fuss."

She had not hesitated to prepare Enrile's downfall with what might fairly be called feminine guile. "Do you know," one of her aides told me, "all the time she was waiting for the right moment to get rid of Enrile she was entrusting him with secret missions?"

"We women," President Aquino said later, "know we have our own timing and our own ways. "

What if there had been a real coup that weekend? "Repel all predatory forces approaching Malacanang," the president had ordered on one particularly tense occasion when, another aide told me, "there were exactly four helicopters under her command."

"If there is a fight," Aquino herself said as she sat in her office, "it will end right here."

That was exactly what happened nine months later, during the pre-dawn hours of August 28, 1987, when Corazon Aquino— having failed to reach her minister of defense, the armed-forces chief of staff, and her executive secretary—called up God.

Mrs. Aquino's cool composure helps explain why, when the bullets start flying, she can be one tough president. It also lets her shrug off the kind of stress that might have broken a strongman long ago.

I talked to a soldier of the Presidential Security Group, which had bravely defended Mrs. Aquino in August. When I complimented him on the good job he and his comrades had done, he said, "Thank you, sir," and added, "Yes, we've kept the boss alive so far, so she can do her job." Then this macho Filipino crossed himself.

He told me a story about the president that a member of her family corroborated later.

Three men from the Presidential Security Group had died on August 28. After the fighting was over, Mrs. Aquino went into the working-class barangays to visit their families. She consoled their wives and children and said the Rosary with them.

When she got back to Malacanang, someone asked her how it had gone. The president said, "Something very funny happened at one of the wakes."

As it turned out, one of the dead soldiers, a stereotypical Filipino male if ever there was one, left behind him not just one wife but three. Certain the president would be there, all three widows had shown up for the wake, demanding the place of honor.

"I smiled at all three," said Mrs. Aquino, "then headed straight into a corner and consoled the mother."

"I've seen her stand down a room full of generals one minute and giggle with her daughter the next," an aide told me. "By the time the August coup was crushed," he added, "I was on the verge of nervous collapse. She went back to her house and went to sleep."

"She enjoys putting down coups d'etat," he said.

"Marcos was the first male chauvinist to underestimate me," she herself once remarked. "He was not the last to pay for that mistake."

A few days after the meeting in her office, I saw President Aquino again at a luncheon meeting with the country's most powerful business and political leaders. The word was she was going to deal with the "weakness" issue. The choice of venue was deliberate: in this same cavernous room in the Manila Hotel, just two years earlier, she'd launched her campaign to bring down Marcos—a possibility that, back then, had also been derided by the strongmen, and much of the press, as absurd.

As she started speaking, people were still finishing their desserts. There were the usual Doesn't-Cory-look-nice-today comments. The president, as usual, explained her blueprint. Once again she outlined her political, economic, and military plans.

Then she said, "The honeymoon's over, isn't it?"

It seemed to be the "isn't it?" that caused a surge of shocked recognition to pulse through the room.

She hadn't just asked, she'd answered, the question that, for months, even her critics hadn't quite been able to formulate. What was the problem? What really explained that sense of anticlimax, of letdown, even when she'd crushed a coup?

Having defined the problem, she also prescribed the solution. It was time for the Madonna of People Power to come down off her pedestal. Time, too, for people to stop blaming Our Lady of Democracy every time their prayers didn't come true. Time, in short, to put a great, romantic moment in Philippine history behind them—and start collecting the trash, filling in the potholes, which, to thunderous applause, she instructed the responsible officials in the audience to do within one week.

"Can she hack it? Is she weak?" People could hardly believe it. Here was Aquino herself asking what most people in the room would not have dared to say to her face.

"[My] style of government by consultation, which I hoped would get your understanding and support, has disappointed you," she conceded. "Henceforth I shall rule directly as president."

She outlined her policy on the insurgency, and concluded, "I have said clearly all that needs to be done." Then she stared straight out at her audience. "Am I also expected to take up an M-16 and do it myself?"

By now it was hard to stop the applauding.

Then Mrs. Aquino took on her enemies. Would the "shamefaced officers" and "failed politicians" find a back door to power ?

"They can forget it," she declared. "Although I am a woman and physically small, I have blocked all doors to power except [through a free presidential election] in 1992." She went on: "Still you ask, is she weak? Again, I say, let my scattered enemies answer that."

She had, she pointed out, something her enemies lacked—"election to the presidency and a mandate for my principles and policies. . . . They lack the one thing the people will never give them: trust.

"I am not sorry the honeymoon is over," she told her audience. "The sooner we get over the fantasy of the honeymoon and face the hard work of marriage—the marriage of president and nation—the better.

Unless you've actually seen her do it, it's hard to appreciate Corazon Aquino's ability to instill in Filipinos—all different kinds of them—not just faith in her but faith in themselves.

"She's smart, she's good, she has a coherent vision, and she's immovable," a businessman named Chito Ayala remarked following her speech. "Besides, she's the only one who can stop them from turning this country into a banana republic."

A couple of hours after Mrs. Aquino's speech at the Manila Hotel, which was televised that night and created great excitement even among the president's opponents, I went over to Malacanang to talk with her press secretary, Teddy Benigno.

I'd expected euphoria among the president's staff, but it was business as usual. If something's scheduled to happen at 3 P.M., the president doesn't like it to happen at 3:15. Also, when she calls, she expects her subordinates to come running. At one point the phone rang, and Benigno ran.

1 told Benigno the president had made the most effective political speech I'd ever heard—not as oratory, but because she'd so uncannily asked, and answered, every question that had been troubling the audience.

"It was about time,'' he said. "You can have no conception of how impossible it is to get her to do something before she's decided the time is right."

Then he said, "Today, for the first time in public I saw the woman I have to cope with in private every day."

Corazon Aquino has always known how to deal with her enemies. Lately she's shown she also knows how to deal with her friends. Over the past six months, she has dismissed dozens of men and women who, quite literally, had dedicated their lives to her cause—strongwilled, brave, and independent-minded people, people more temperamentally suited to overthrowing a dictatorship than carrying out the daily chores of a functioning democracy.

"I'm tired of having a Cabinet of superstars," she explained. "I want people who will obey me."

The most prominent of those dismissed was the president's executive secretary. Joker Arroyo. Everyone agrees that Arroyo was totally honest, totally loyal to the president—also a totally incompetent administrator who angered and humiliated people who thought they, not just he, should have free access to the president. Everyone was also in agreement that President Aquino delayed far too long in dismissing him, just as, earlier, they had agreed she delayed far too long in dismissing Enrile.

I wonder. Mrs. Aquino has an intuitive ability to sense at exactly what moment certain men are no longer dangerous—and no longer useful—to her.

The August night that mutinous troops got to within five hundred meters of her bedroom, many extremely competent officials telephoned to say they'd be right over just as soon as the shooting stopped.

Arroyo didn't need to be telephoned. He was already on his way to the palace, heedless of the dangers. He carried out her every order during those crucial hours—except the one that, politically, was the most important.

"You're not to say a word against Ramos," she'd told him, referring to General Fidel Ramos—leader of the constitutionalist, loyalist mainstream of the Philippine armed forces, the officer who with agonizing slowness, following painstaking staff preparations, finally did implement her order to crush the rebellion with maximum force.

Yet the next day, when everyone should have been celebrating and congratulating Ramos, Arroyo was telling everyone that the general had wavered. A firestorm of public outrage descended not on those who had plotted the coup but on the president's closest adviser, coming far too close to the president herself. "Joker's got to go," she announced a few days later. "I'll do it over lunch."

Arroyo walked up the stairs from his office on the ground floor of the Malacaiiang guesthouse into the presidential office and closed the door. "We could hear the screaming down here," a receptionist told me. "He kept shouting, 'I stood by you and your husband for sixteen years. I stood by you and your husband for sixteen years.'

No one heard what the president said, because Cory Aquino did not raise her voice, but when I asked her what had been her greatest mistake as president, she replied, "I guess in the beginning I was very trusting and that I felt when people said, 'We want to help you,' they really meant it. And I supposed a great many of them did. But there were others, perhaps, who had other motives other than just helping me. And so maybe that's a mistake on my part, or what you might call a failing in that one shouldn't trust everybody."

She went on: "It's always been my policy to give everybody the benefit of the doubt. But I suppose in everything in this life you have to find the right balance— not being too skeptical, not being too trusting either. So I have learned that much as I would like to believe that everyone is sincere and would like to help, sometimes it isn't so."

She'll never resign. She'll never give in. She'll never stop trying. If she keeps growing and learning as she has so far, I suspect she'll be hard-pressed not to accept a second six-year term in 1992.

Of course, they just might kill her. During his twenty years in power, Ferdinand Marcos corrupted every national institution. But there's a difference between corrupting the judiciary, say, and corrupting the military. The difference is, soldiers have guns.

In Manila a journalist friend named Lin Neumann, who, over the years, has been consistently more pessimistic than I about both Cory Aquino's prospects and the Philippines' future, summed up the situation with precision.

"Seventy to eighty percent of the Filipino people," he said, "support Cory and support democracy. Ten to fifteen percent on the extreme right and extreme left are determined to overthrow her and democracy by any means they can. The real question is, can the center hold?"

"Oh, sure! Yes, of course," Aquino answered when I asked her that, "because if it couldn't, I wouldn't be here! I mean, if it weren't holding, I would have been out of here!"

Normally I'm against using italics and exclamation points. But they're necessary if you're to convey any sense of how Philippine English is spoken. It's lilting, like Irish English. It's also brisk and emphatic, with the stress, especially as President Aquino speaks it, often on the last word of the sentence.

She added, "But, of course, the two extremes have to try their best, and they will resort to any means to get me out of here."

The men with guns in the Philippines are just like most Filipinos. Most of them support democracy. An even larger majority just want peace.

But bullets aren't like votes. It doesn't take 51 percent of the bullets to oust a leader. It takes just one. And while this fact appalls the vast majority in the Philippines, it fills certain others with hope, even glee, as I discovered one night in Manila at a dinner attended by people considered experts on the Philippines.

These people derided me for even trying to write a profile of Corazon Aquino, because, as one of them put it, it was "inevitable" she would be forced from power.

I challenged them to lay their reputations on the line and to say when, exactly, this would happen.

These people made the same predictions some people have been making about Mrs. Aquino ever since she took office.

One, a woman with ties to both the insurgent left and the multimillionaire exile opposition, said, "She'll be gone in two months."

The second, an American banker who's been in the Philippines for more than ten years, said, "Four."

The third, a British journalist who'd just finished his "Whither the Philippines" piece and would be off to Djakarta the next morning, said, "1 give her a year, at most."

This dinner had been held in Ermita, which is called the "Tourist Belt" of Manila, though it doesn't attract many tourists these days, because of the widespread impression the Philippines is a country going down the tubes. The Filipinos are a small-statured brown people, with a propensity for silly nicknames and a cheerfulness in the face of adversity that seems to offend some visitors more than the adversity does. Since Ninoy Aquino's death, which struck some deep chord within millions of them, they have demonstrated enormous courage and a knack for making things consistently turn out better than the "experts" predict.

As I walked back to my hotel, it was clear the streets of Ermita were no Utopia. I saw prostitutes there, as well as beggars, bars, and nightclubs. But 1 also passed late-night grocery stores, churches, and many newsstands, along with a restaurant called the Hobbit House, staffed entirely by dwarfs. If this was a "damaged culture," I decided, I nonetheless preferred it to the company of the people I'd just left. It was not the pessimism of my dinner companions I could not understand. It was their optimism, why they were so very hopeful Mrs. Aquino would fail.

"One last question!" exclaimed the president briskly.

"Oh, my heavens," I said, startled by the authority in her voice. "All right. You do keep to schedule. I knew that."

"I have to," she said. "Otherwise ..."

For my last question, I told her about that dinner party—about the two months, four months, twelve months. I asked her, "Will you still be—"

Before I could say "alive" or "in power," she said, "Well, before, when I announced my candidacy, I think a number of people not only living here but I guess foreigners were saying, 'No way can she defeat Mr. Marcos, and no way can Mr. Marcos be removed from the presidency.'

"Well, that is my answer to these people who are saying that I'll be gone in two months, four months, or whatever. I'll see this thing out, don't worry."

Her voice speeded up as she said the ritual good-byes. Her smile was replaced by a look of hectic concentration. Mrs. Aquino was already focused on the next item on her agenda. Before I knew it, I was out of the room.

She has, I realized as 1 walked downstairs, quite a knack for getting rid of people when their time is up.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now