Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAs the Reagan era draws to a close, I. F. (Izzy) Stone is reaping the recognition long due him.

March 1988 Christopher Hitchens Nigel DicksonAs the Reagan era draws to a close, I. F. (Izzy) Stone is reaping the recognition long due him.

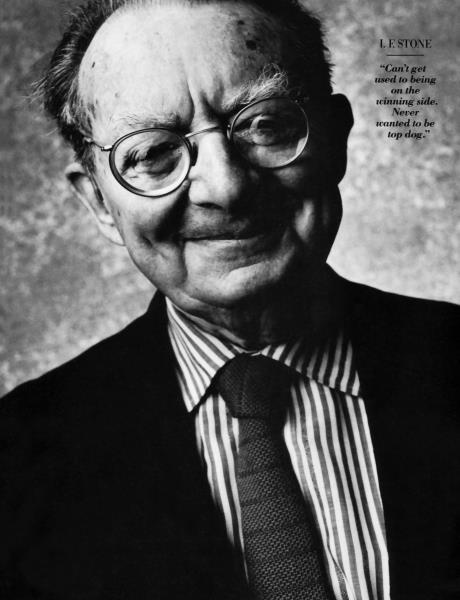

March 1988 Christopher Hitchens Nigel Dickson I. F. STONE "Can't get used to being on the winning side. Never wanted to be top dog."

I. F. STONE "Can't get used to being on the winning side. Never wanted to be top dog."

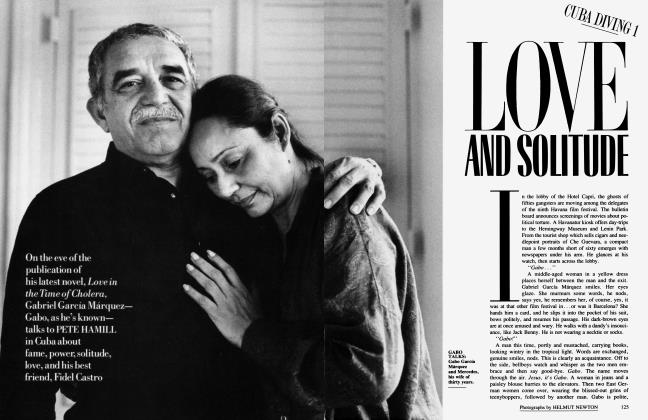

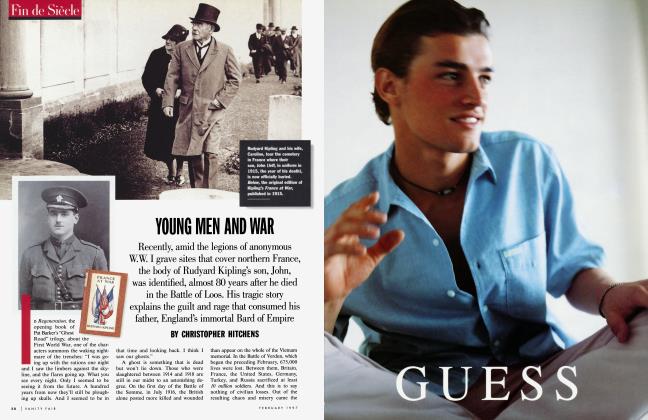

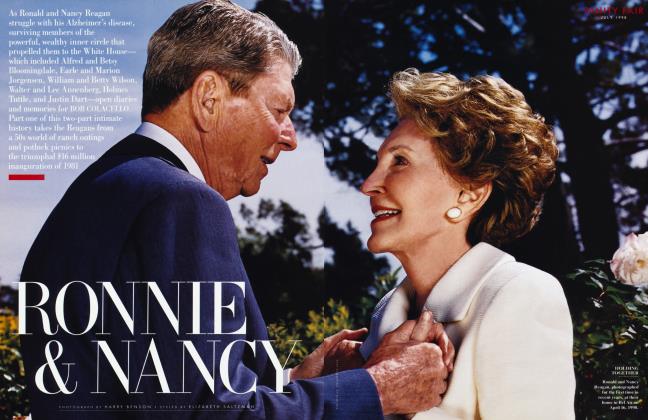

As the Reagan era draws to a close, I. F. (Izzy) Stone is reaping the recognition long due him. The Trial of Socrates has just been published, his collected works are due out in the fall, and a biography of "America's most celebrated radical journalist" is appearing this month. At eighty, Stone has lived to see himself vindicated as the Cassandra of the Vietnam catastrophe. Copies of his famous one-man sheet, I. F. Stone's Weekly (1953—71), launched as a single-handed corrective to the torrent of official propaganda and obfuscation, change hands as collector's items. Old Washington sweats who ignored or derided him when he was politically active are quick to slap his back and heap him with credit. But gloating is somehow foreign to his nature: "Can't get used to being on the winning side," he says. "Never wanted to be top dog."

It's idle to say that Stone has no successor, more pertinent and more worrying to point out that he has no emulators. Izzy has always scorned the herd mentality of modern journalism; he once told David Halberstam that he admired the Washington Post because you never knew on what page you would find a page-one story. Rereading his columns can provide eerie moments. In February 1979 he warned of the danger in letting the Shah of Iran into the U.S., and asked, "What if the new Iranian regime makes demands of its own? What if someone in our military has been giving their military promissory notes of American help?" What indeed? As for the Greeks, so often presented as the essence of the democratic ideal, if they were so pure and noble, how come they put Socrates to death? Stone set out to teach himself Greek and to pursue this conundrum of antiquity for himself. In the epilogue to The Trial, breezily entitled "Was There a Witch-hunt in Ancient Athens?" he assesses the work of the experts and rules that they got it all wrong. Most probably, he concludes, they have been misinterpreting satirical plays as depictions of the real thing. Not bad for a retirement project.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now