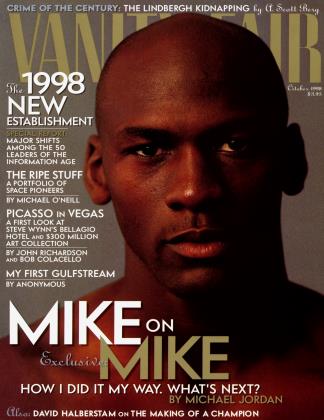

Sign In to Your Account

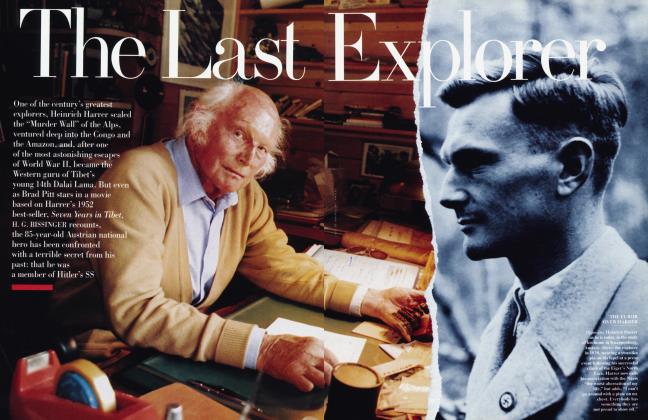

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

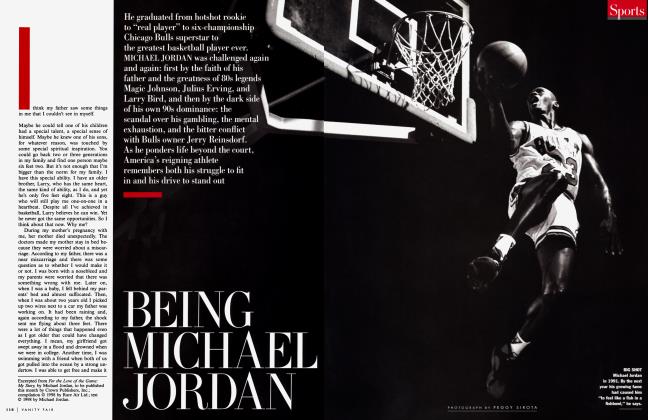

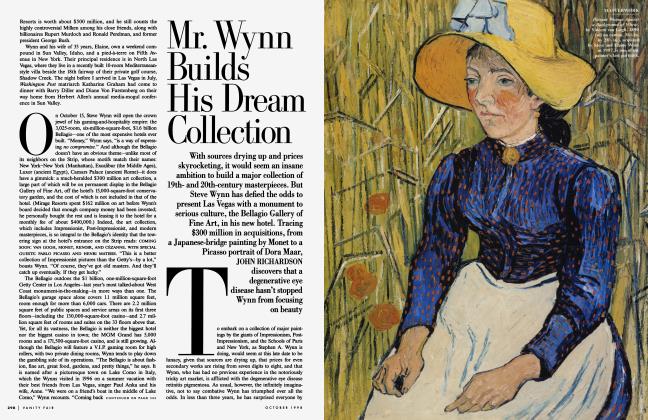

PICASSO COMES TO VEGAS

Casino mogul Steve Wynn already owns three Las Vegas hotels—the Mirage, Treasure Island, and the Golden Nugget—but his heart is in his fourth, the 3,025-room, six-million-square-foot, $1.6 billion Bellagio, opening this month, which houses a $300 million art collection, an 1,800-seat theater, a host of luxury businesses such as Tiffany, Chanel, Armani, and Petrossian, and nine V.I.E villas, each with a personal spa. Touring one of the most expensive hotels ever constructed, BOB COLACELLO takes the measure of its builder, whose father was a compulsive gambler, whose friends include Rupert Murdoch, Ronald Perelman, and former president George Bush, and whose dreams are his blueprint for action

Suppose somebody built a hotel in Las Vegas that was the best hotel in the world, the best hotel that had ever been built. Suppose somebody built the greatest hotel of all time—of any century on any continent. This is not just flapjawed developerspeak. Think about it. Cesar Ritz opened the Ritz in Paris in 1898. Architecture, materials, technology are all way beyond that now. And what's so magic about the Place Vendome anyway? The monument to Napoleon is too skinny—I don't like the proportions. The Oriental in Bangkok is tired. The Regent in Hong Kong is fabulous on that harbor, but it's only got a small piece of land. So if someone did that—built the greatest hotel of all time—wouldn't it make people who never came to Las Vegas want to come? If there was a hotel so pre-emptive in its loveliness—not a themed place, with a theme like pirates or Rome or Egypt. But just romantic in a literary sense: a lovely place, perfect, even nicer than the real world. To paraphrase George S. Kaufman: the way God would do it if he had money. Suppose there was a place so lovely and romantic that there was no argument that it was the best one in the world. That it wasn't, like, 'I still think the Connaught's nicer.' No, this would be, like, 'O.K., O.K.—what's second?''"

The man making this pitch—and building that hotel—is Steve Wynn, the 56-year-old chairman and C.E.O. of Mirage Resorts, Inc., which already owns and operates three major hotel casinos in Las Vegas: the upscale, tropical-themed Mirage and the midmarket, pirate-themed Treasure Island, each with about 3,000 rooms, on the Strip, and the venerable 1,900-room Golden Nugget downtown, the first casino Wynn acquired, back in 1973. With the possible exception of his arch-rival, Donald Trump, Steve Wynn is the most famous name in the casino business, due largely to a series of television ads he made in the 1980s with Frank Sinatra. And, by most accounts, only the legendary and secretive Kirk Kerkorian, the octogenarian Las Vegas billionaire who controls MGM Grand, Inc., has been as successful at turning slot machines into cash cows. According to Bear, Steams senior managing director Jason Ader, an analyst of the casino, hotel, and leisure industries, "Steve Wynn is the leader whom everyone in gaming looks to emulate."

Wynn was one of the first fledgling entrepreneurs to be propelled into the big time by junk-bond wizard Michael Milken, who helped him finance a second Golden Nugget, in Atlantic City, which he opened in 1980 at a cost of $ 160 million and sold seven years later to Bally Manufacturing for $440 million. Today, Wynn's 14 percent stake in the publicly traded Mirage Resorts is worth about $500 million, and he still counts the highly controversial Milken among his close friends, along with billionaires Rupert Murdoch and Ronald Perelman, and former president George Bush.

"To paraphrase George S. Kaufman: the way God would do it if he had money."

Wynn and his wife of 35 years, Elaine, own a weekend compound in Sun Valley, Idaho, and a pied-a-terre on Fifth Avenue in New York. Their principal residence is in North Las Vegas, where they live in a recently built 10-room Mediterraneanstyle villa beside the 18th fairway of their private golf course, Shadow Creek. The night before I arrived in Las Vegas in July, Washington Post matriarch Katharine Graham had come to dinner with Barry Diller and Diane Von Furstenberg on their way home from Herbert Allen's annual media-mogul conference in Sun Valley.

On October 15, Steve Wynn will open the crown jewel of his gaming-and-hospitality empire: the 3,025-room, six-million-square-foot, $ 1.6 billion Bellagio—one of the most expensive hotels ever built. "Money," Wynn says, "is a way of expressing no compromise." And although the Bellagio doesn't have an obvious theme—unlike most of its neighbors on the Strip, whose motifs match their names: New York-New York (Manhattan), Excalibur (the Middle Ages), Luxor (ancient Egypt), Caesars Palace (ancient Rome)—it does have a gimmick: a much-heralded $300 million art collection, a large part of which will be on permanent display in the Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art, off the hotel's 15,000-square-foot conservatory garden, and the cost of which is not included in that of the hotel. (Mirage Resorts spent $162 million on art before Wynn's board decided that enough company money had been invested; he personally bought the rest and is leasing it to the hotel for a monthly fee of about $400,000.) Indeed, the art collection, which includes Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and modem masterpieces, is so integral to the Bellagio's identity that the towering sign at the hotel's entrance on the Strip reads: COMING SOON: VAN GOGH, MONET, RENOIR, AND CEZANNE. WITH SPECIAL GUESTS: PABLO PICASSO AND HENRI MATISSE. "This is a better collection of Impressionist pictures than the Getty's—by a lot," boasts Wynn. "Of course, they've got old masters. And they'll catch up eventually. If they get lucky."

The Bellagio outdoes the $1 billion, one-million-square-foot Getty Center in Los Angeles—last year's most talked-about West Coast monument-in-the-making—in more ways than one. The Bellagio's garage space alone covers 1.1 million square feet, room enough for more than 6,000 cars. There are 2.2 million square feet of public spaces and service areas on its first three floors—including the 130,000-square-foot casino—and 2.7 million square feet of rooms and suites on the 33 floors above that. Yet, for all its vastness, the Bellagio is neither the biggest hotel nor the biggest casino in town; the MGM Grand has 5,000 rooms and a 171,500-square-foot casino, and is still growing. Although the Bellagio will feature a V.I.P. gaming room for high rollers, with two private dining rooms, Wynn tends to play down the gambling side of its operations. "The Bellagio is about fashion, fine art, great food, gardens, and pretty things," he says. It is named after a picturesque town on Lake Como in Italy, which the Wynns visited in 1996 on a summer vacation with their best friends from Las Vegas, singer Paul Anka and his wife, Anne. "We were on a friend's boat in the middle of Lake Como," Wynn recounts. "Coming back from lunch in the little town of Bellagio to the Hotel Villa d'Este, where we were staying. And Annie Anka says, 'Bellagio is such a mellifluous word.' So we look it up in the ItalianEnglish dictionary we had. It says, 'A place of elegant relaxation.' What a name for a hotel! All four of us go: 'Yay! Bellagio! That's the name of the new hotel!'"

CONTINUED ON PAGE 342

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 298

Lake Como and its greater environs also inspired the Bellagio's overall look and style. "The notion of a shoreline with a village built into it, and that romantic, lovely architecture that you see everywhere on the Riviera, and from the Costa Smeralda to the Lombardy lakes," explains Wynn, who designed the hotel with Mirage Resorts inhouse architect DeRuyter Butler and decorators Roger Thomas and Janellen Sachs Radoff, as well as California architect Jon Jerde. "They've all got it," he continues, "the Spanish tile roofs, the twoor threestory buildings with lovely gardens and balconies, human-scale buildings in stucco in pastel shades. It's sort of a universal symbol of the good life, of a place to get away."

For starters, he had an 11-acre lake dug out across the front of the hotel's 90-acre site—the former Dunes Hotel-Casino & Country Club, which came with abundant water rights. Several hundred feet back, a Mediterranean village of restaurants and shops—all ocher stucco and terra-cotta tiles and plate-glass windows—emerges out of the water. A few multicolored domes lend a Venetian touch, and the hotel's main entrance is approached by a covered bridge, vaguely Florentine in style, which ascends from the Strip along one end of the lake, and has a people mover inside it. A quarter-mile-long balustrade lines the lake along the Strip, for pedestrians to lean on while listening to Italian opera from the speakers hidden in its columns and watching the dancing fountains that shoot 200 feet into the air. Rising above the entire Chirico-esque assemblage is a three-winged skyscraper, topped with an illuminated cupola.

"It is obviously the pursuit of excellence come to life," Wynn says of his dream hotel. That's why, he believes, he has been able to attract an unheard-of array of international designer boutiques and top-notch big-city restaurants to Las Vegas, including Armani, Chanel, Hermes, Gucci, Tiffany, and the Madison Avenue jeweler Fred Leighton, as well as branches of Sirio Maccioni's Le Cirque 2000 and Osteria del Circo from New York, Aqua from San Francisco, and Olives from Boston. Jean-Georges Vongerichten, the chef and co-owner of New York's Jean Georges, Vong, and Jo Jo, is opening a steak house called Prime, and, Wynn says, "Petrossian came to us and said, 'If you'll put our name on a bar, we'll give you caviar at cost forever.' So we're going to have a piano bar and serve high tea and caviar every day, and it's called the Petrossian Bar." There will also be a restaurant named Picasso, run by Julian Serrano from San Francisco's Masa's, where Wynn will hang Picasso paintings, which he refers to as "decorative Picassos—you know, nothing over $3 million."

'The part of the symphony that is the most difficult is the entertainment," Wynn tells me. "We said from the very beginning that the entertainment centerpiece of Bellagio has to be as remarkable as the hotel itself. People have to talk about it in Singapore and Johannesburg and Paris and New York." He is sitting in his office in the Mirage hotel, wearing a royal-blue collarless silk shirt, dressy black slacks with a black alligator belt, black suede shoes, and a gold watch. He is tall, tan, fit, with a full head of charcoal hair and jet-black eyes, which he tends to lock on you, perhaps to compensate for his failing eyesight due to retinitis pigmentosa, the degenerative disease with which he was diagnosed at 29. Behind his burled-blond-wood desk, hanging on the floor-to-ceiling glass walls that look out onto a palm garden where half the grass is real and half is AstroTurf, are an eight-foot-long Jackson Pollock drip painting from the 1950s and an abstract de Kooning from the same period. His office also contains an orange "flag" painting by Jasper Johns, a small Robert Rauschenberg, and two Andy Warhols—Campbell's Elvis, which was owned by Salvador Dali, and a small Orange Marilyn, which New York art dealer Larry Gagosian sold him for about $3 million from S. I. Newhouse Jr. (whose family owns the company that publishes Vanity Fair) after the latter bought a larger Orange Marilyn for $17.3 million at Sotheby's earlier this year; sculptures by Giacometti and Brancusi; a globe made of semi-precious stones and rare metals, which was a gift from his brother, Ken Wynn, who oversees Mirage Resorts' construction projects; and a framed Bachrach photograph of Colin Powell, in his four-star general's uniform, autographed, "To my buddy, Steve Wynn."

Facing Wynn, in head-to-toe black Calvin Klein, is Sandy Gallin, the Hollywood talent manager he has lured to Las Vegas to take charge of all entertainment—from lounge acts to show-room extravaganzas—at all Mirage Resorts hotels, including the Beau Rivage in Biloxi, Mississippi, which is opening early next year, and Le Jardin in Atlantic City, which Wynn plans to build by 2002, despite Donald Trump's legal efforts to keep him from returning to New Jersey. Gallin was recommended to Wynn by their mutual friend Barry Diller. He has turned his clients at the Gallin-Morey Agency, including Dolly Parton, over to his longtime partner, Jim Morey, and is now chairman and C.E.O. of Mirage Entertainment and Sports, a subsidiary of Mirage Resorts. "I have dealt with a lot of very creative people in the business, and Steve's right up there," Gallin says of his new boss. "And I'm talking about Neil Diamond and Michael Jackson and Richard Pryor. For me, Steve's a modern-day combination of Mike Todd, Walt Disney, and Barnum and Bailey."

Gallin points out that Wynn already has "the two largest-grossing live attractions in the world"—Siegfried and Roy at the Mirage and the Cirque du Soleil's Mystere at Treasure Island. "They both perform at 99.6 percent capacity, and they've been there for years," he says, noting that each theater seats 1,500 and has two shows a night, five nights a week, at $88 and $70 a ticket. At the Bellagio, Wynn has built an 1,800-seat theater for a new Cirque du Soleil spectacle titled O—a play on the French word for water, eau, and a reference to the fact that the 10,000-square-foot stage can be transformed into a million-and-a-half-gallon pool in the flick of an eyelash. The show features 68 young Olympic-level swimmers, divers, and gymnasts from France, Germany, China, South Korea, and Mongolia, as well as this country. "The theater, and the entertainment attraction that's in it," Wynn says, "is an attempt to be one of the most lyrical and overwhelming sensory experiences ever."

While I am in Wynn's office, he and Gallin discuss everything from staging Broadway shows in Las Vegas to whether to hang a pair of large 1977 de Koonings on either side of the Bellagio's front desk. "The question is would the public recognize de Kooning," wonders Wynn. "Or would I be hanging a $2 million picture for nothing?"

"Maybe you can call it the De Kooning Registration Desk," suggests Gallin.

In the middle of a meeting with a Bellagio convention-sales executive, two deliverymen walk in with a Magritte painting of two men in bowler hats and hold it in front of Wynn's desk for his consideration. Bruce Willis calls Wynn from Sun Valley to make plans for the weekend. Charlie Rose calls from New York to see about getting Wynn on his show again. A jeweler arrives from Los Angeles with the almond-size diamond ring Wynn is giving his wife for their 35th anniversary, and Wynn takes it out of its blue velvet box to show Gallin. "D-flawless," he says. "I wanted Elaine to have something perfect." He has one of his secretaries get Bill Bible, the chairman of the Nevada State Gaming Control Board, on the phone, to complain about an investigator asking what he considers devious questions. "Every time we open a new hotel I get reinvestigated," he tells me. "And that's fine. I've been doing this for 30 years. I've never had a negative vote." Then he asks the secretary to play the video of the collected television spots he made for the Golden Nuggets with Sinatra, Dean Martin, Kenny Rogers, Dolly Parton, Paul Anka, Cathy Lee Crosby, and his mother, Zelma.

When I ask him how the Bellagio project came about, he launches into an hourlong saga, beginning with the purchase of the old Dunes Hotel-Casino & Country Club in early 1993, from the Sumitomo Bank, after the Japanese businessman who owned it ran into financial difficulties, for the bargain-basement price of $70 million. "We congratulated ourselves," Wynn recalls. "We danced around. We had bought 166 acres for $400,000 an acre. And we owned a golf course and a hotel. We blew up the hotel as a publicity stunt for Treasure Island—you know, to underscore our opening." A few months before Treasure Island opened in October 1993, Wynn had traded 40 acres of the Dunes golf course to developers—who later merged with Circus Circus—in exchange for 50 percent ownership of the hotel they built on the land, the $345 million Monte Carlo, which opened in 1996. "So my cost on the [Bellagio property] was nada. We had 126 acres free and clear."

Late in the afternoon of the second day I spend with Wynn, he takes me on a tour of his hotel in progress. Driving down the Strip, we pass his competitors' latest projects: Sheldon Adelson's $1.2 billion Venetian, which is built around a Grand Canal, and Hilton's $750 million Paris Las Vegas, which will have a half-size replica of the Eiffel Tower directly across from the Bellagio. As his chauffeured Lincoln Navigator turns onto the Bellagio construction site, Wynn says, "I think we've got 3,200 guys on the job right now. And girls." He points out the 18-acre temporary nursery filled with trees from the Dunes golf course, which are being replanted around the Bellagio. "This is the road we're building from behind the Mirage all the way to the airport," Wynn says when we hit the back of the property. "It's a mile long, and we're landscaping it and giving it to the county. It's going to be called Frank Sinatra Boulevard." Running parallel to that road will be a monorail for the trams that will connect the Monte Carlo to the Bellagio and the Bellagio to the Mirage, which is already connected to Treasure Island.

We enter the Bellagio through the rear employees' entrance. "This is as nice as most hotels' front entrances," Gallin says as we walk through an enormous foyer covered with stained-glass skylights and lined with ficus trees in terra-cotta pots. We tour the convention center and the meeting facilities, including the 45,000-square-foot large ballroom and the 25,000-square-foot small ballroom, the conference rooms named for artists (Van Gogh I, Van Gogh II), and the wedding chapels, which have built-in video cameras and pews upholstered in salmon moire. "For $80 or $90 we'll produce a video of your wedding that looks like it cost $20,000," Wynn said. "You pick out the music and we do the rest." From the windows of the Palio coffee bar, we look out at the three swimming pools, one of which can be closed off for private pool parties, and all of which will be surrounded by formal Italian gardens. Outside the Cirque du Soleil's theater, Wynn points to the wall where "the [Fernand] Leger tapestry's going." Inside, I ask about a futuristic chrome chandelier. "It's a surprise," Wynn says. "When the show begins, it has people in it. Breathing people. Humans."

"Steves a modernday combination of Mike Todd, Walt Disney, and Barnum and Bailey'' says Sandy Gallin.

He leans a hand on Gallin's shoulder as we make our way down wide hallways littered with construction debris. On the third floor, we poke around one of the nine villas, which are reserved for major celebrities and the highest of the high rollers. It has three bedrooms, with his and hers bathrooms, a living room, a dining room, a kitchen, and a powder room, as well as a personal spa, consisting of a mirrored exercise room, a massage room, a sauna, and a beauty parlor. Wynn is proud of the gasfueled fireplace that floats in the glass wall between the living room and the patio. It was his idea, he says. The villa's total square-footage: 6,200, not counting the 3,000-square-foot patio with its lap pool, Jacuzzi, and Renaissance-style fountain. Across the hall from the villas are "entourage rooms"—"For friends or security or secretaries," Wynn explains. "They have a bedroom and a sitting room. They're really petite suites. So nobody's roughing it."

On the 17th floor, in a lilac-and-green suite with a gold-framed print of a Monet painting on the living-room wall, Wynn is annoyed by the look of the bedroom carpet. "We have a mistake here," he hisses into his cell phone. "I remember telling you distinctly I did not want bordered carpets around the beds.... And here it is right in my face." When he hangs up, he says, "That won't be there when the hotel opens, I assure you." He also orders every lightbulb in the hallway sconces switched from 25 watts to 15.

His mood brightens when we return to the first floor and he shows me a 30-by-70foot coffer in the lobby ceiling where a $10 million chandelier by Seattle artist Dale Chihuly will be installed. "It's a huge glass sculpture of a bouquet of flowers, made of 2,164 pieces of glass. And the flowers are vermilion and yellow and purple and red.

... It's an explosion. It's three times the size of his biggest museum piece. It's the largest glass sculpture ever, according to Dale. In the world!

"This is the most dramatic part of the hotel," he goes on as we enter the conservatory. "The botanical garden. We've got four different scenes—summer, fall, winter, and spring. Every 90 days we change for the season, and then in each of the four seasons the blooms last for 30 days. The hotel's smell and look change every 30 days. We're going to open in October with an explosion of orange. I want it to be monochromatic on opening night. See that hallway over there in the comer? It's 14 feet tall and 14 feet wide. That's the connection to the greenhouse, which is 90,000 square feet. We have 111 people in the horticulture department of this hotel. We can make a season change in 18 hours—three nights, six hours a night, on the graveyard shift. In the spring, we've got fullsize cherry trees—like in Washington."

To our left, an enormous curved marble staircase sweeps up to what Wynn says will be the separate ladies' and gentlemen's spas. Ahead of us, next to the Cafe Bellagio, are the ticket office and the entrance of the Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art. Wynn explains that guests will enter through a museum gift shop.

As we head toward the front door and porte cochere, where Wynn's driver is waiting, he says, "When you come into the hotel, everything about it is nongaming. The lobby, the gardens out front, the gardens inside, the beauty spa, the bar, the stores—you have to take a right turn to go to gamble.... Now, when people come out, this is a cobblestone place here, and that's a very formal garden over there. The tunnel to the left is where we pop up the taxicabs, because we won't let them park on the curb. They're underneath here, and they've got their own break area—bathrooms, vending machines, air-conditioning—so that they'll like us. But there are no cabdrivers leaning against their cars with cigarettes dangling out of their mouths. They come up that ramp when we press a button—one at a time."

I ask Wynn if the verdigris metal and glass covering the porte cochere were inspired by the Galleria, Milan's late-19thcentury precursor of a shopping mall. "That's one of my favorite places," he answers. "That's where I got the idea. I said, 'That's a great look. Let's use verdigris metal. But it has to be real. No faux.'"

"Steve, am I right in saying that the difference between this hotel and the other hotels in Las Vegas," asks Gallin, "is that everything here is real?"

"Everything," says Wynn.

"Real plants," says Gallin.

"Yes, and real limestone," says Wynn.

"Real tile," says Gallin.

"Not the look of," concludes Wynn. "Now, what is not real is this rock wall on the side of the driveway."

"That's not real?" I ask.

"No, that's FGRC. Fiberglass-reinforced concrete."

On my third day in Las Vegas, I have lunch with Elaine Wynn, in the clubhouse at the Shadow Creek golf course. A tall, slim blonde who was once Miss Miami Beach, she is a director of Mirage Resorts and has been involved in her husband's business from the beginning. "I realized early on that this was a man who was ambitious and dynamic, and that I'd better be along for the ride," she says. "Fortunately, he's allowed me to be a partner.... There are things that he doesn't see that I'll bring to his attention, and vice versa. I've made him more sensitive to opera, for example. And the irony is that I was the great art enthusiast at first. But when he gets into something, he takes it to dimensions that I never envisioned. I've always been modest in my personal consumption, if not in my wish list. He acts on his wish list."

They met in Miami Beach in 1960, when he was a sophomore at the University of Pennsylvania and she was a freshman at U.C.L.A. "I came home for Christmas break," she tells me. "Our fathers fixed us up. We had a date, and it took."

Both of their fathers were compulsive gamblers. Wynn's father, who had been born Michael Weinberg, ran bingo parlors on the East Coast and rented a cabana for his wife and two sons at the Fontainebleau hotel in Miami Beach. He died during heart surgery at age 46, in 1963, leaving behind tens of thousands of dollars in debts. That same year Steve Wynn married Elaine Farrell Pascal, and together they started to turn the bingo business around. Their first daughter, Kevyn, was born in 1966, and their second daughter, Gillian, was born in 1969. Today both daughters work for Mirage Resorts.

In 1967 the Wynns moved to Las Vegas. He bought a 3 percent stake in the Frontier Hotel casino, which he sold after investigators found that it was owned by Detroit mobsters. He then ran a liquor distributorship. In 1972 he bought a lot on the Strip from Howard Hughes for $1.1 million, sold it to Caesars Palace for $2.25 million, and bought a 5 percent interest in the Golden Nugget. A year later, at age 31, he took control of the Golden Nugget and began transforming it from a seedy gambling joint into the first four-star hotel in downtown's Glitter Gulch. Sixteen years later he opened the $730 million Mirage, the most opulent—and profitable—hotel on the Strip. Treasure Island, another hit, followed in 1993.

"We have 111 people in the horticulture department of this hotel. We can make a season change in 18 hours! says Wynn.

Along the way the Wynns divorced and remarried. "We made a midcourse correction," she says. "We had a very short separation. I was in Sun Valley. He was in Atlantic City. He called me every day. He didn't want me to resign from the company. People thought we were crazy. We were crazy. You don't really know what you have until you are confronted with the fact that you might lose it." She pauses and adds, "I proposed the second time. We got married on the same day at the same place—the Waldorf-Astoria on June 29. The girls made all the arrangements. That's the nice thing about a second wedding. Your children can be there."

In July 1993, Kevyn Wynn was kidnapped. After paying a ransom of $1.45 million, the Wynns decided it was time to move up from the tract house they had bought for $385,000 in 1978. The house they built at Shadow Creek was designed by the same team that is building the Bellagio. It has everything from a flower painting by Georgia O'Keeffe, one of Elaine's favorite artists, in the hall to a fireplace in the master bathroom for winter nights when the desert temperature can drop to the low 30s.

After lunch Elaine Wynn shows me around the clubhouse. In the men's locker room, there is a brass plaque on each louvered locker door bearing the name of a friend of the Wynns'—President Bush, Kevin Costner, Vic Damone, Michael Milken, Bill Gates, Kerry Packer, Will Smith, R. J. Wagner, Paul Anka, James Garner, Andre Agassi, Bruce Willis, Cheech Marin, Tom Selleck, Steve Lawrence, Clint Eastwood, Jack Nicholson, Kenny Rogers, Randy Quaid, Don Johnson.

I ask Steve Wynn about his plans for the Bellagio's opening.

"It's not rent-a-star. We're past that. I don't want to overload everybody with paparazzi bullshit. I'm going to invite about 1,000 people, and that includes the press. So it's going to be a severely restricted event—there'll be tremendous squealing. What I'd like to do is have all the V.I.P.'s arrive on Thursday and Friday. Thursday night, when we cut the ribbon and inaugurate the lake and fountains, we'll have Van Cliburn play the 'Bellagio Theme,' which David Foster composed for us—it's wonderful, like Mantovani. We'll probably have fireworks by Grucci—Sandy and Elaine are deciding how far to go with this. Friday we'll give everybody a free night. I want the invited guests to have a chance to check out our incredible collection of restaurants. And if you're a shopper, how about Armani and Chanel? There'll be 100,000 people on the Strip trying to get in, but I'm going to severely restrict the public that comes in. The centerpiece of Saturday night will be the premiere of the show. Then we're going to have a gala in the ballroom. I want a full symphony orchestra, and maybe we'll have Andrea Bocelli sing—he's the 40-year-old blind Italian opera singer who's all the rage in Europe. I would like the opening to have a very special tempo. You know when you see Prince Philip and the Queen walking? I would like the tempo of the evening to be like that for my guests. I want them to move slowly and be able to take everything in."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now