Sign In to Your Account

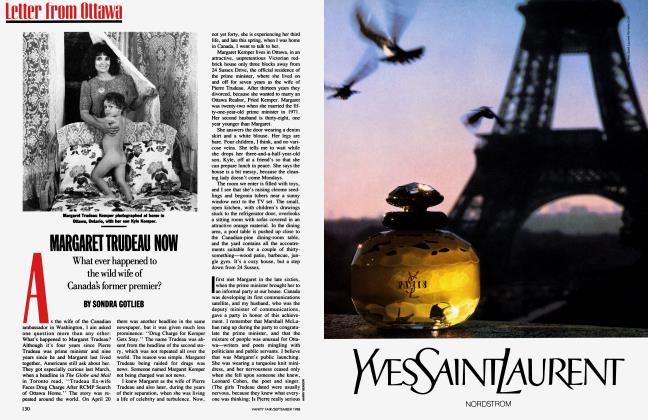

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

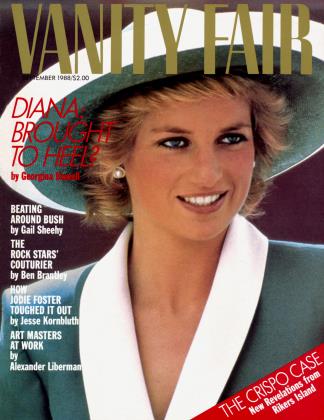

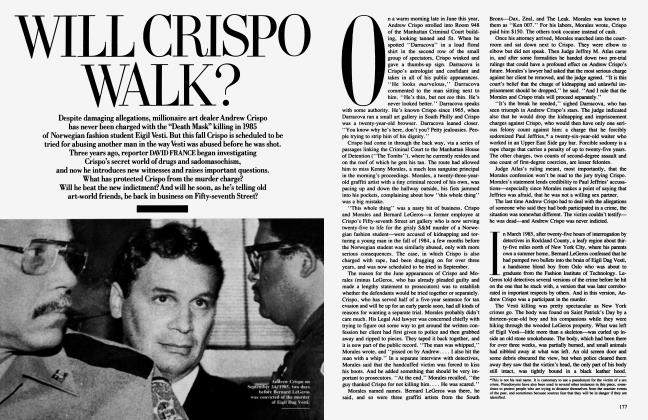

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWill LeGeros Talk?

Since his murder conviction, Crispo's "lieutenant," Bernard LeGeros, has kept silent. Now, before Crispo's new trial for forcible sodomy, in an exclusive interview with MAURY TERRY, LeGeros hints that he may testify against the man who introduced him to a world of drugs, sex, and violence

MAURY TERRY

As Bernard LeGeros appears in the doorway of the small, litter-strewn conference room at Rikers Island prison in New York, my mind goes back to September 1985, when he stood trial in a nearby suburban courtroom, charged in a sensational murder case. He didn't speak publicly then, and hasn't since, about the pre-dawn hours of February 23, 1985, when a young, Norwegian, homosexual fashion student named Eigil Dag Vesti entered an automobile in Greenwich Village and vanished. A month later his charred body was found in a smokehouse on the property of United Nations executive John LeGeros, Bernard's father, in Tomkins Cove, Rockland County, about thirty-five miles from Manhattan.

"I learned from him how to stare at people to frighten them. Andrew has that way about him that control."

"I remember you from my trial," he says. At twenty-six, with his thin mustache, dark swept-back hair, and midnight eyes, Bernard LeGeros has the look of a shy Sal Mineo. He is passive, docile, even affable, clearly one of life's followers. It is hard to believe his violent history. Convicted of the Vesti murder, sentenced to twenty-five years to life in jail, he is awaiting the start this month of another criminal trial, in which he, an individual named Kenneth Morales, and the millionaire art dealer Andrew Crispo are accused of luring a young graduate student to Crispo's midtown art gallery, where he was allegedly beaten and tortured, and also sodomized by Crispo.

LeGeros has pleaded guilty to attempted kidnapping in the case, and speculation is rampant as to whether he will testify against Crispo, his former friend, mentor, and employer.

Andrew Crispo. The name still clings to LeGeros wherever he goes, like a shadow.

''We call him Ace," LeGeros says quietly as he slides onto a rickety bench in the conference room. Outside, a guard shuts the door and padlocks it, and we are left alone. Still, the din from a steady flow of inmate traffic in the hallway impedes our conversation, for LeGeros is extremely soft-spoken.

''You never really get used to it around here," he observes. "It's quieter upstate—I was at Clinton in Dannemora—but my family's nearby and I can see them once a week as long as I'm here."

He lights a cigarette. "You called me Crispo's slave in your book [The Ultimate Evil, which features material on Crispo]. My parents told me you were right. I was always trying to please him. I learned from him how to stare at people to frighten them. He has that way about him—that control. I guess I probably wouldn't be where I am if it wasn't for him."

"He took the Fifth at your trial, and he walked. He wasn't even charged," I say. "How do you feel about that?"

"He also tried to get immunity first," LeGeros interjects. "But they wouldn't give it to him. What does that say to you about his being there?"

"The D.A.'s office believes he was there," I say.

"Look," LeGeros responds, "I know all about having to have independent corroborating evidence. But I can't figure out what went on in Rockland. There is other evidence that he was up there that night—some strands of his hair and a black half-glove of his, for instance. He was also seen with Vesti in the city that night. And that mask on Vesti was Andrew's. People had seen it. He used to carry it around in a bag sometimes. Maybe it's because of his money and connections—but I don't know," LeGeros adds, his voice trailing off.

LeGeros's younger brother, David, testified that Crispo had told him that the rifle that killed Vesti was hidden in his Fifty-seventh Street art gallery, where it was subsequently found. David LeGeros also informed police that Crispo had told him that he was "safe" on the Vesti killing because he kept dossiers on a state-police official and a number of judges and politicians. Crispo's files, if they exist, apparently relate to bizarre homosexual activities and cocaine trafficking on the part of these public servants. However, David LeGeros was never asked to convey this information to a grand jury, or called to testify about his conversations with Crispo. And despite public vows of forthcoming justice from District Attorney Kenneth Gribetz, who prosecuted LeGeros, Crispo has not been indicted in Rockland County, although the case technically remains open there.

"I think Gribetz is only a politician. He's afraid to go up against an excellent criminal lawyer like the one Crispo has," LeGeros says, with resentment.

LeGeros contends that he has been harassed and threatened on a number of occasions since his imprisonment. "I saw Andrew in the bull pen recently," he tells me. The bull pen is a holding area in the Manhattan courthouse. "He said, 'I'm surprised to see you're still around.' I knew what he meant by that, so I challenged him to try something." LeGeros pauses. "He was also talking about you. He said, 'This guy and his book have given me a permanent headache, and something should be done about it.' That's his way now that he's inside. On the street he was much more direct when he wanted something done. Now it's hints. You know, something subtle. He was still feeling me out, trying to see if I'd be willing to make a phone call outside—which I'd never do. I'll tell you, take away his list of special phone numbers and he'd be powerless."

He shakes his head. "I used to think he was my friend. I thought he was great to me. He was an orphan, and I admired the way he came up from that to be as successful as he was, and he was very successful. He was beaten in that orphanage, and I think he kept reliving it with the S&M stuff."

"But didn't he use you?" I ask him.

"Yeah, he did. And he kept on trying. I mean, he once alluded to an awful lot of money if I took the fall on the Rockland case, and I'm aware of some indirect hints about this Manhattan trial too."

LeGeros has appealed his Rockland County conviction, and therefore is reluctant to delve into the events surrounding Vesti's murder. He does say, however, "It started out as one of Andrew's games, a game he'd played many times before. I thought it would be just that. I never believed until it was too late that it would go as far as it did."

Vesti, he insists, was not an unwilling passenger on the ride to Rockland County. "He and Andrew were into their thing. Vesti thought it was all a game too."

Listening to Bernard LeGeros in his bleak surroundings, you cannot help but ask, What was it that turned his life upside down and led this troubled but intelligent youth from a highly respected family to murder?

His mother, Dr. Racquel LeGeros, a research scientist who specializes in the study of calcium phosphates, has a ready answer: "His brother, David, said to me, 'Mom, how can this be? This was my roommate for more than twenty years.' It was the cocaine and Crispo— that's how it came to be."

A native of the Philippines, the raven-haired Dr. LeGeros travels all over the world to participate in conferences and lecture about her work. In the past few months she has attended professional gatherings in Thailand, France, Japan, and South Africa. She and her husband, John, a physicist who is associated with the United Nations Development Program, an agency that administers aid to Third World countries, both stood staunchly beside their son during his three-week murder trial in September 1985. But by then it was too late.

The oldest of the four LeGeros children, Bernard was bom on April 6, 1962. His brother attends college and is an army first lieutenant. His sisters, Katherine, nineteen, and Alessandra, fifteen, are both students. The family divides its time between the Tomkins Cove property and an apartment on Manhattan's East Side.

"From the very beginning, things were difficult for Bernard," his mother says. "He had a complicated birth, one where for a while they feared it might be either his life or mine. It didn't turn out that way, but he apparently went without oxygen for a time, and he didn't develop fully emotionally after that, I've been told. It wouldn't have happened today, but in 1962 medicine wasn't as advanced as it is now.

"Bernard was always very anxious and upset about people leaving him alone, or leaving him behind. Good-byes are very hard on him, and they always have been. He has this fear. When he was fourteen months old, we sent him to live with my family in the Philippines for about a year. He was treated wonderfully when he got there, but looking back I wonder if—even though he was an infant—the very long trip and separation from me had a negative effect on his development. I don't know, but I do think about it."

Bernard's father, John, who grew up in South Dakota, testified at the Vesti trial. "There were warnings," he said. "I didn't heed them and that was a mistake." He was referring to his son's early patterns of violence, macabre obsession, and suicide attempts. In one week in 1980, when he was eighteen, Bernard LeGeros slashed his wrists and also hung on ropes from the roof of the thirty-seven-story Manhattan apartment building in which his grandparents lived until he was coaxed to safety by security guards. In 1982 he swallowed cyanide. On the last two occasions he was admitted to Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan, and both times—the second time against the advice of a psychiatrist—he was released when his father promised to secure private psychological counseling for him.

Crispo came to know that the rapid tapping of a coke spoon on a wooden table would indicate tension and evoke in Bernard a desire to placate him.

"I convinced them I had the means and would immediately arrange for him to have psychiatric treatment," John LeGeros told the Rockland County court. "I discovered later I was unable to manage Bernard."

I remember LeGeros's parents and brother at his trial, fighting back tears and struggling to maintain their composure as Bernard's entire life was exposed to them.

Bernard, his father has acknowledged, felt rejected and victimized by the demands of his parents' careers. As an infant, he was boarded with a nurse in Yonkers, New York, five days a week and later attended a metropolitan-area grammar school. His life changed dramatically in 1970 when John LeGeros gave up his computer work in the private sector and joined the United Nations staff. The transition marked the onset of a somewhat nomadic existence for the family, and planted in Bernard the seeds of his "good-bye" syndrome.

At the age of thirteen, he was enrolled in the Pierrepont School in Great Britain while his father served with the U.N. in Yemen and his mother remained in New York, absorbed in her work. Bernard balked at his isolation, and was subsequently permitted to drop out of Pierrepont in order to join his father in the Middle East.

Continued on page 250

Continued from page 185

"Bernard was angry that I was still in New York," Racquel LeGeros says. "But John and I were trying very hard in our own careers—maybe too hard. We really wanted the best for our children—to give them a better start in life."

In Yemen, Bernard and David witnessed several public executions of criminals, which they later described to their mother. "I was very upset that they saw such things," she says. "But John didn't know that they had done so."

After returning to New York, Bernard attended La Salle Academy in Manhattan and graduated in 1980. That autumn he entered New York University's School of Continuing Education, and also that year he made his first suicide attempt.

In 1982 he became something of a hero. Walking on the street one day, he witnessed a pair of muggers approach a couple and snatch the woman's purse. LeGeros gave chase, wrested the pocketbook away from the thieves, and returned it to the shaken couple, who happened to be the mayor of Tel Aviv and his wife. LeGeros was oveijoyed when he received an official letter thanking him for his bravery.

After earning an associate-in-arts degree in 1984, he signed up for some cinema and television courses at the university's Tisch School of the Arts. He was also interested in photography and painting. "I like to work on canvas with oil," he says. "I lean toward Neo-Abstract Expressionism, Neo-Surrealism, and realism."

After a few months, he dropped the film courses. "He had some emotional difficulties," his Vesti-case attorney, Murray Sprung, recounted. This was a real understatement. By the middle of 1984, LeGeros had changed his life completely.

Looking back, he agrees with his mother on the causes of his decline and fall: Crispo and cocaine. "The two C's," he says. He is also quick to exonerate his parents. "I did feel rejected and alone," he says, "but they were trying to do their best all along. I don't blame them—they tend to blame themselves. What happened to me happened to me. Crispo saw that I was vulnerable and he took advantage. But I feel sorry for what I've done to my family—not what any of them has done to me."

After meeting Andrew Crispo, Bernard LeGeros lost his grip on the real world and drifted into a make-believe existence. "I was looking for something, and I thought he was the answer, but he sure wasn't. I became a prisoner of my own momentum. I allowed fantasy to rule reality."

LeGeros is heterosexual, which makes his allegiance to the notoriously gay Andrew Crispo even more puzzling on the surface. But if, as he says, he was searching for an authority figure who would provide the direction and guidance he desperately wanted, and believed he was lacking, Crispo was quick to identify the young man's weaknesses.

"He was very effective," Racquel LeGeros says bitterly. "He came to where he would tell Bernard to write down what bothered him, what made him angry, what upset him—all his emotions and what triggered them."

It was not surprising, then, that Crispo came to know that the rapid tapping of a coke spoon on a wooden table would indicate tension and evoke in Bernard a desire to placate him. LeGeros paints a disturbing picture of himself in those years when he first met his Mephistopheles.

In December 1977, fifteen-year-old Bernard LeGeros had an after-school job in a travel agency in which his uncle was a partner. The uncle had met Andrew Crispo in Southampton and socialized with the art dealer's summer set. One day LeGeros delivered travel tickets to the gallery. There he and Crispo engaged in a friendly discussion about art. LeGeros liked the man.

In 1982 LeGeros returned to the gallery to discuss job possibilities with Crispo, who suggested that Bernard pore through art magazines in order to determine the type of work he'd like to pursue. A year later, in April 1983, LeGeros was having problems with his studies at N.Y.U. and was going through a difficult period in his relationship with a girlfriend. Once again, by fate or magnetism, he was drawn to Crispo, and that time, he says, he and Crispo shared a line of cocaine at-Crispo's apartment on West Twelfth Street.

That summer, LeGeros says, he introduced the girlfriend to Crispo, and they "did coke with Andrew and another friend of his at Crispo's apartment." Meanwhile, LeGeros was running into resistance on the home front, as his parents became more and more concerned about their son's life-style. Needing a shoulder to lean on, LeGeros chose Crispo's.

Step by step, as LeGeros explains it, he was enticed into the Crispo galaxy of cocaine, limousines, parties, and more cocaine. As LeGeros became more and more enmeshed with Crispo, so the art dealer came increasingly to rely on his faithful Bernard, who was ready to cater to Crispo's every whim.

Crispo, according to LeGeros and other acquaintances, was fond of playing games, including S&M scenarios. Occasionally, a young man would be invited to the gallery after hours to participate in these activities. Sometimes LeGeros would dress up as a security guard and carry a billy club or a handgun. And sometimes, as Crispo looked on, an initially willing partner would turn reticent as LeGeros and others mercilessly whipped him for hours. Things were clearly getting out of hand, as Crispo spoke of snuff films, perhaps in jest, and LeGeros absorbed every word, every nuance. Cocaine now ruled their world, along with the accompanying illusions of invincibility and manifestations of animalism and paranoia.

Meanwhile, LeGeros was enduring yet another "good-bye," one that he says affected him deeply. On August 24, 1984, his girlfriend left for an extended vacation in Romania. "I felt depressed and suicidal," LeGeros tells me. "So I called Andrew, and he told me to come to the gallery. We did coke together and talked about a job with him." Shortly thereafter, Bernard LeGeros was put on the payroll at the Andrew Crispo Gallery.

Crispo, LeGeros recalls, "left me with a sense of power and relief that day. I also felt a strong sense of loyalty and affection for Andrew; he cared about me." Crispo departed for Nantucket for the Labor Day weekend, leaving LeGeros in charge of his apartment. From Nantucket, Crispo spoke regularly with LeGeros by telephone. "I felt trusted and needed," LeGeros says, "and decided I was willing to do whatever I could to prove my loyalty to Andrew."

Part of that loyalty, LeGeros acknowledges, was playing his role in the S&M scenes that were growing more and more violent, and more and more frequent, throughout the fall of 1984. LeGeros rapidly became Crispo's enforcer, and Crispo would jokingly refer to him as "my bodyguard" and "my executioner."

But LeGeros, despite his deteriorating mental state, still held on to a degree of humanity. "Sometimes, unknown to Andrew, I'd deposit someone at the hospital if things got out of control."

With hindsight, it seems clear that tragedy was inevitable. It just happened to be named Eigil Dag Vesti.

LeGeros is unable to discuss the Vesti murder, but according to testimony at his trial in 1985, Crispo had told him to shoot Vesti twice—once to kill his body and once to kill his soul. An act of necrophilia was also performed by Crispo, LeGeros alleged.

After LeGeros was arrested, he says, he told authorities that he had been with Crispo all night and nowhere near the Rockland County estate. Crispo, LeGeros claims, "told them he wouldn't be part of my alibi.'' After that, he says, he felt no loyalty to Crispo.

Bernard LeGeros, who has been in prison three years, shows an objectivity he lacked at the time of his last trial. He spends his time in prison writing letters, socializing with other inmates, participating in an inmate-run group-therapy program, visiting with his family, studying his trial transcript, and pondering his possible appearance at Crispo's upcoming trial in Manhattan.

As I get up to leave, he hands me some of the papers on which he writes down his thoughts. The first entry I look at reads: "I am overwhelmed with sorrow for what I have done to them. To rephrase what Pablo Neruda once wrote: '. . .for from each crime were born the bullets that have this day found within me where my heart lies.'"

He points out another item to me, and says, "This about sums it up." It's a rewrite of some lines by Dra2a Mihajlovi, a Serbian guerrilla who had been sentenced to death by Tito's government:

I found myself in a whirl of events and intrigues.

Some I created and some others created for me.

I found destiny was merciless towards me when

It threw me into the most difficult whirlwinds. I wanted much.

I began much.

But the whirlwind—the world whirlwind Carried me and my dreams away.

Now, as Andrew Crispo waits to go on trial, Bernard LeGeros seems strangely calm. "He's afraid I just might decide to testify against him," he says. There's a pause. "So let him wonder about it."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now