Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMARGARET TRUDEAU NOW

Letter from Ottawa

What ever happened to the wild wife of Canadas former premier?

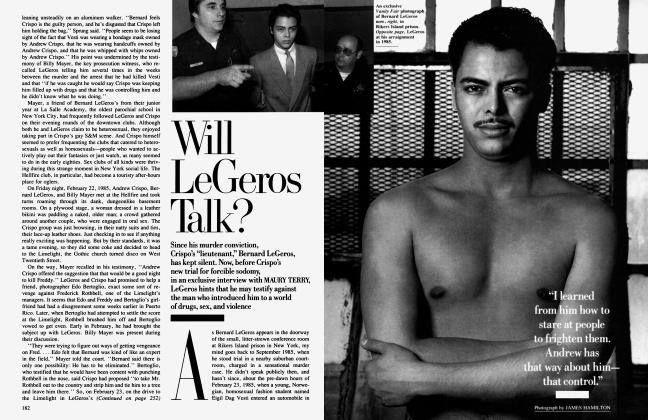

SONDRA GOTLIEB

As the wife of the Canadian ambassador in Washington, I am asked one question more than any other: What's happened to Margaret Trudeau? Although it's four years since Pierre Trudeau was prime minister and nine years since he and Margaret last lived together, Americans still ask about her. They got especially curious last March, when a headline in The Globe and Mail in Toronto read, "Trudeau Ex-wife Faces Drug Charge After RCMP Search of Ottawa Home.'' The story was repeated around the world. On April 20 there was another headline in the same newspaper, but it was given much less prominence: "Drug Charge for Kemper Gets Stay." The name Trudeau was absent from the headline of the second story, which was not repeated all over the world. The reason was simple. Margaret Trudeau being raided for drugs was news. Someone named Margaret Kemper not being charged was not news.

I knew Margaret as the wife of Pierre Trudeau and also later, during the years of their separation, when she was living a life of celebrity and turbulence. Now, not yet forty, she is experiencing her third life, and late this spring, when I was home in Canada, I went to talk to her.

Margaret Kemper lives in Ottawa, in an attractive, unpretentious Victorian redbrick house only three blocks away from 24 Sussex Drive, the official residence of the prime minister, where she lived on and off for seven years as the wife of Pierre Trudeau. After thirteen years they divorced, because she wanted to marry an Ottawa Realtor, Fried Kemper. Margaret was twenty-two when she married the fifty-one-year-old prime minister in 1971. Her second husband is thirty-eight, one year younger than Margaret.

She answers the door wearing a denim skirt and a white blouse. Her legs are bare. Four children, I think, and no varicose veins. She tells me to wait while she drops her three-and-a-half-year-old son, Kyle, off at a friend's so that she can prepare lunch in peace. She says the house is a bit messy, because the cleaning lady doesn't come Mondays.

The room we enter is filled with toys, and I see that she's raising cleome seedlings and begonia tubers near a sunny window next to the TV set. The small, open kitchen, with children's drawings stuck to the refrigerator door, overlooks a sitting room with sofas covered in an attractive orange material. In the dining area, a pool table is pushed up close to the Canadian-pine dining-room table, and the yard contains all the accoutrements suitable for a couple of thirtysomething—wood patio, barbecue, jungle gym. It's a cozy house, but a step down from 24 Sussex.

I first met Margaret in the late sixties, when the prime minister brought her to an informal party at our house. Canada was developing its first communications satellite, and my husband, who was the deputy minister of communications, gave a party in honor of this achievement. I remember that Marshall McLuhan rang up during the party to congratulate the prime minister, and that the mixture of people was unusual for Ottawa—writers and poets mingling with politicians and public servants. I believe that was Margaret's public launching. She was wearing a turquoise knit minidress, and her nervousness ceased only when she fell upon someone she knew, Leonard Cohen, the poet and singer. (The girls Trudeau dated were usually nervous, because they knew what everyone was thinking: Is Pierre really serious this time?) She was an unknown, unlike some of his dates, such as Barbra Streisand, even though her family was prominent. Margaret's father, James Sinclair, had been a minister in the Liberal Cabinet under former prime minister Louis St. Laurent. It is easy to remember that evening, because Margaret Sinclair was the most ravishing girl I had ever seen.

On March 4, 1971, she married the prime minister, and they were a mythic duo—Pierre, the Jesuitical logician whose motto was "Reason over passion" and whose Kennedyesque style turned Canadian housewives into Trudeau groupies, and Margaret, the unreasonable romantic, whose gods were Buckminster Fuller and Janis Joplin. The flower child from Vancouver sewed her own wedding gown, baked the wedding cake, and organized a secret family wedding—even the priest had no idea who the groom would be. Within the next five years Margaret gave birth to three boys, the first two bom precisely two years apart on Christmas Day. Although she was almost always pregnant, she campaigned for her husband before his second election, accompanied him on official trips, decorated their residences, and entertained royalty, presidents, and prime ministers.

Two events from this period stand out in my mind. The first occurred just after Margaret arrived in Ottawa as Pierre's wife; it was an evening party for women, given by the wife of a member of the prime minister's staff. A dazed Margaret sat on a sofa surrounded by older women who tried to draw her out with talk about the weather, comparing the benefits of the heavy snowfalls of her new home, Ottawa, with the grievous drawbacks of Vancouver rain. She barely spoke, and at the first opportunity she dashed out, well before the rest. We didn't know how to approach such a beautiful and young prime minister's wife. The previous one had been almost fifty years older. Naturally, we were also jealous. Margaret was a magical girl living in a magical world, a fabulous princess who had everything, including Prince Charming. At the wave of her wand, Mounties would whisk her away to her palace at 24 Sussex, where maids ironed her Ungaros and Valentinos, and she had a government plane to fly her anywhere on earth to meet famous people. She was the envy of every woman at that party, yet she acted distant, wary, and unhappy.

The second event was a dinner at the prime minister's residence, to which the prime minister and his wife invited a few public servants, ministers, and friends who had children the same age as theirs. The flutist Jean-Pierre Rampal gave a concert before dinner. Most of the guests had never been in the prime minister's residence during Margaret's reign, and were expecting place cards, prancing waiters, and protocol. We all arrived grossly overdressed. I remember I wore an antique amethyst necklace given to me by my mother-inlaw. Margaret wore a peasant skirt and carried a baby on her hip, and we were told that she had prepared all the food herself. The uneasy guests were mollified by quantities of Russian caviar, which the Trudeaus had brought back from a state visit to Moscow. Tired already of official parties, Margaret had decided to give an informal, neighborly buffet. She seemed a little confused, but she had a trembly warmth about her and was eager for the party to be a success. The prime minister was, as usual, a little remote.

After the birth of her second baby, the public began to realize that she hated formality and protocol and was determined to add spontaneity to her official life. Soon no one, including her, had any idea what she was going to do next. She might faint when the Queen was speaking, or stand up at a state dinner and sing a song to the wife of the president of Venezuela, or scream an obscenity at her husband in front of ranks of Japanese dignitaries on the steps of Akasaka Palace.

In 1974 the newspapers said that Margaret had had a nervous breakdown and was recuperating in Montreal. In 1975 she had a third son, Micha. Then, in March 1977, right after their sixth wedding anniversary, headlines announced that Margaret had left her husband and three children to party with the Rolling Stones. That was the public demise of Margaret's official life as wife of the prime minister of Canada.

She said in Consequences, the second of two books of confessional memoirs, "I thought being the Prime Minister's wife was important. It isn't. What counts is being a complete person first and then tackling life out of your own strengths and weaknesses." Her subsequent behavior, however, belied her words. She wasn't as ready for public retirement as she claimed.

Her second life began during this period of semi-separation from her family, when she became Margaret our Lady of the Concorde, jetting with famous names from New York to London, staying at the Savoy and the Carlyle. The simple Vancouver girl who had boiled jam at Harrington Lake (the country residence of the prime minister) now became an Andy Warhol-type celebrity. Cameras followed her everywhere, and book and movie offers rolled in. She gave television interviews and studied acting and photography. She was "searching for her truth," as Pierre put it, and she was free to do what she wanted. There were liaisons with Jack Nicholson, Ryan O'Neal, and a number of businessmen and politicians.

She wrote of this new life in Consequences. "When I wasn't staying in fancy hotels... or eating at the Connaught ... I was crossing the Atlantic on Concorde. There is nothing like Concorde for the ritzy life. I didn't even bat an eye when on one trip I found ex-Beatle Ringo Starr across the aisle and tennis star Jimmy Connors directly behind me. Wasn't I part of the Concorde set?"

Steve Martindale, a Washington lawyer, who acted as Margaret's agent during this time, said, "You have no idea what it was like being with her. Not only was she incredibly beautiful, she was wife of the prime minister. Everyone wanted to meet her. I would buy coach tickets for us on transatlantic flights and we were automatically bumped up to first class. She hated the press following her about, but if they weren't there she'd ask,

'Where are the cameras?' "

Her last sighting during this period was when the cameras caught her dancing at Studio 54 in New York the night Pierre Trudeau lost the Canadian election. That was May 22, 1979. "I might no longer love Pierre, but I felt stricken by his defeat, and the shame, hurt and humiliation were mine just as much as his. I saw doom all around me," she wrote in Consequences. "I took a bottle of champagne from the fridge and tried to open it with my teeth until my friends, who had just returned, seized it from my mouth. The cork shot off into the ceiling. A minute more and it would have blasted into the roof of my mouth. I was too mortified to care. Then, against all their advice, I insisted on going out to Studio 54. It was there that the press found me... the gayest, most indifferent person in the world. And it was as such that they portrayed me to the world the next day: dancing, as it were, with my 'naked midriff' and niy 'dishevelled hair,' over my husband's political pyre.... Next morning I was horribly ashamed."

Margaret's third life began very shakily in 1979. Using the advance money from her first book, Beyond Reason, as a down payment, she bought the house she lives in now, and appeared to settle down.

'I left all that life in London, New York, and Paris behind me, like a bottle of perfume," she tells me.

She is chopping onions for our lunch. I ask her if it has ever bothered her, living so close to her former official residence but not in it. She laughs. "It's heaven.... I wouldn't trade this life for anything. I hated the feeling of people pussyfooting around, the feeling of being watched." She's beautiful, and serenity has replaced the freneticism I remember from ten years ago.

There were rumors then that she was suffering from manic-depression, and with difficulty I ask her if that was so. ' 'They thought that I was suffering from manic-depression, and that was one of the things that brought me back here," Margaret explains. "The problem was that I wasn't manic-depressive; I was either in the fast lane or the slowest of the slow. I was on lithium for about six months, and I never went out. I never saw people. I saw my children. I ordered food in over the phone from the local stores. I just got fatter and fatter and watched soap operas. The lithium didn't help, because it takes away the manics and the lows, but it leaves you pretty unimaginative." She says about the doctors who prescribed her lithium and Tofranil, "It was the most irresponsible kind of drugging."

"I left all that life in London, New York, and Paris behind me, like a bottle of perfume."

While she was on these drugs, a Japanese company offered her $20,000 to do some publicity in Japan, and she needed the money to pay her mortgage. "I had to start working," she says. Without any medical supervision, she weaned herself off the Tofranil and lithium and came back into the world.

Margaret had done some experimenting with various substances during her Studio 54 period, and she believed that "drug abuse, not mental instability, had been the cause of my major symptoms all along."

The trip to Japan benefited her morale and her pocketbook, and she later found work in Ottawa as co-host of a morning TV show, which lasted several years. Except for the headlines last March, her name disappeared from the press.

I was living in Ottawa when Margaret's first book was published, and many people considered it shocking for her to write a kiss-and-tell memoir while Trudeau was still prime minister. In addition, her publisher went bankrupt, and Margaret never received her royalties from Beyond Reason, which amounted to $400,000. Since I am a writer myself, I knew that it had taken considerable courage for her to tell her story. I no longer saw her as the perverse princess, but rather as someone almost catastrophically confused and overwhelmed by the various worlds in which she had lived— the world of the sixties, the world of wandering freedom, the world without rules, the world of officialdom and protocol, the world of motherhood, the world of glamour, publicity, and stardom. Margaret did not know in which world she belonged or wanted to be. She did not know how to position herself or stay pegged in any orbit. Slowly I began to see her as a victim, a tragic one in the Greek sense, since she was victimized by forces she had set loose upon herself and could have controlled. Somehow this also helped me to see her as human.

We carry our trays onto the back porch and sit in the sun. She has told me on the phone that she doesn't know why anyone would want to interview her, because she isn't a celebrity anymore.

"What's there to say?" she repeats. "I met Fried, and now we lead a life that's very rich. We're busy and contented and very involved with one another. He's the right sort of man for me, whereas Pierre was obviously the wrong sort of man. Pierre is such a thinking man. He likes to be alone. And Fried is very gregarious and down-to-earth. I live within a tight, small group of friends and family. We ski, swim, and do a bit of traveling." A lot of her new friends have children the same age, and Margaret, whose preferred restaurant was once the Connaught in London, now lunches regularly with them at McDonald's. She's expecting another child early next year.

"My life is a dream come true. The three boys live with Pierre in Montreal, but I see them most weekends. We split the holidays—half Christmas holidays, half spring break for Easter, half summer holidays. Kyle loves to see his brothers. We're all just one big extended family, which is wonderful."

She talks about her unhappiness during the worst period of her first marriage. "I was still trying to figure out whether I was a glamorous jet-setter, or a fussy prime minister's wife, or a hippie mother. I tried on all different cloaks."

I ask her if she misses her former lives—the parties, the shopping, the attention she received, the famous names she wrote about in Consequences: Princess Yasmin, Lauren Bacall, Christopher Reeve, Liza Minnelli, Bob Dylan, the Niarchos sons, Jack Nicholson, Bianca Jagger. Plus all the world figures she had met and liked before she separated from Pierre—the Aga Khan and Sally, his wife, Fidel Castro, Pope Paul VI, and Chou Enlai, who complimented her because she wasn't embarrassed by her femininity the way Chinese women were.

Margaret's smile is wistful. "I miss being exposed to the leading thinkers of the world. I do miss that. And I always think of New York as the best place for a romance. But you have to know when to exit. That's the most important thing I learned." She says again, "You have to know when to exit. I'd rather be planting my garden than doing that level of partying and living on the edge of a dream. I couldn't keep the pace of it. It's just not for me."

It's not as if she hasn't had opportunities to go back to her former life, she tells me. "I did audition for a big film recently in Toronto. A film from a book by Mordecai Richler, about an Eskimo. They wanted me to play a Leona Helmsley type, a hateful woman who owned twenty-six hotels."

But the stretch limousine that met her at the airport reminded her of her past, and she wanted to go home. "It was a joke. I'm not back in that world. If they made movies in Ottawa, I'd be happy. My husband, Fried, is old-fashioned. He's got very set notions about wifely duties. Fortunately, he has a great sense of humor, and he adores me."

I ask her about the marijuana episode in March. "It was terribly painful for me and my family. But everyone was wonderful, including Pierre. Good friends called from all around the world to give me support, and reassure me, just everybody ... the little old ladies I visit at the old people's home, the people in the dry cleaners', the people in the grocery store."

I ask her what happened. Around noon a postal truck delivered a small package mailed from an unknown address in Vancouver. She left it unopened and went to pick up her child at school. When she returned and opened the package, she found that it contained a small amount of marijuana, less than an ounce. (She was later accused of sending it to herself, but she was in Jamaica the day it was mailed.) About fifteen minutes later the police arrived and asked for the package. There was no search of her house, although they had a search warrant. Margaret gave them the package. An Ottawa Citizen car appeared at Margaret's door ten minutes after the police left. The press knew about "the raid" before she had time to call her lawyer. Later the charge was stayed, because the police had bungled the search warrant. "The press just gave it another dimension. The charge would have been dropped, because I was innocent."

Margaret assumes that the package was sent by an envious paranoid, a "sicko" who wanted to see Margaret Trudeau suffer. She says she doesn't smoke marijuana since she's been married to Fried, because he disapproves.

"There was a time I really cried," she says, "not for myself, but for my children. I just felt so badly that I was once again causing waves, and I hadn't even caused them."

Margaret says that in her new life she can be free of exploitation by trusting very few people outside of her good friends.

"You are not allowed to be real when you are the prime minister's wife, not even to yourself. There is always somebody you have to be putting on a show for—covering up and hiding your feelings. I do not know of any wife in a public position who has not suffered."

As to her life just after she left the prime minister, she says, "I was dealing with tremendous mental anguish. Tremendous."

She still goes dancing, but not to places like Studio 54. She goes with Fried to a little place called Spinners Pub, where they play sixties music. "Most of the people there are in their sixties," Margaret Kemper says, laughing, "but it's fun."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now