Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

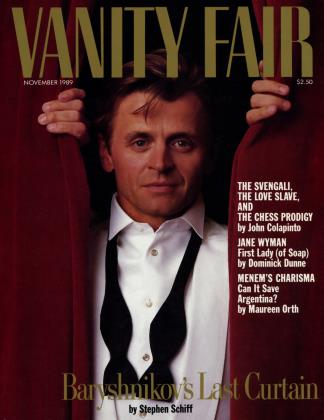

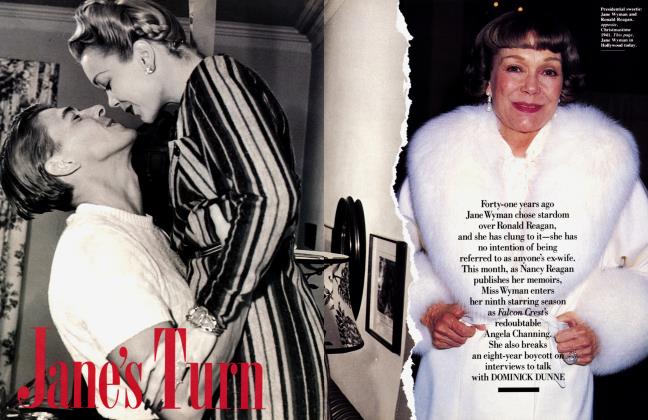

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE MOBSTER AND THE PRIEST

Crime

Vincent "the Chin" Gigante is the Howard Hughes of organized crime— and his brother the wealthy priest counsels Cardinal O'Connor

OWEN MORITZ

Vincent "the Chin" Gigante, the reputed boss of New York's 250-member Genovese crime family, is nervous, insomniac, weird, and maybe schizophrenic. His own men, according to a recent newspaper account, have been caught on wiretaps referring to him as Aunt Julia. Nevertheless, law-enforcement agencies maintain, he's president and chief executive officer of an enterprise doing $100 million a year in illegal gambling, labor racketeering, narcotics, loan-sharking, hijacking, and corruption in the building industry. In the Mafia's corporate standings, the Genovese family is rated just below John Gotti's Gambino family as the most powerful in America. But whereas Gotti is a well-known personality in the media through the efforts of the Eastern District of the U.S. Attorney's Office, the Chin remains a man of mystery.

Vincent Gigante is partial to the night. One investigator who has shadowed him for years says he's the most nocturnal of the crime chieftains. "He's like an owl," the agent told me. "He sleeps in dribs and drabs." In the company of one or two of his close associates, he has been spotted schlepping along Greenwich Village's darkened sidewalks in a bathrobe, pajamas, and slippers. He talks to himself and mumbles incoherently if he is approached by strangers, especially strangers affiliated with the law. He whiles away the daytime hours playing pinochle in the musty-looking Triangle Social Club on Sullivan Street, and he doesn't really get down to serious business until after midnight.

Then he will get into the backseat of a gray stretch limo and motor up to a stunning town house with thick red doors on East Seventy-seventh Street, the home of Olympia Esposito, his mistress and, according to F.B.I. agent Lawrence S. Ferreira, the mother of three of his children. This used to be the digs of former Roulette Records president Morris Levy, who was convicted in Camden, New Jersey, last year on extortion charges, along with Dominick "Baldy Dom" Canterino, the Chin's alleged righthand man. Levy paid $525,000 for the house in 1981 and sold it in 1983, when it was worth at least $1 million, to Olympia Esposito for an astonishing $16,000. Levy has since been accused of being a conduit for Genovese-family money.

If the Chin is under particular stress, he will not spend the night on Seventyseventh Street, but will return to the Village, possibly to the Sullivan Street apartment of his frail eighty-seven-yearold widowed mother.

F.B.I. agents once trailed him to this apartment with a subpoena to appear in court. They searched the place until they found the Chin naked under an umbrella in the running shower. Another time, agents went to the Triangle Social Club searching for a weapon they believed had been used in the slaying of a police officer in Queens. One of the agents stepped inside and asked the Chin to come out. When he appeared, reluctantly, the agents were stunned. Gigante, who at sixty-one is a hulking presence with hard features and closely cropped dark hair, was standing before them looking like Li'l Abner, with his pant cuffs six inches above his shoes, wearing white socks on his large feet. Yet he was perfectly able to satisfy the agents that what they had come looking for wasn't on the premises.

He is not just lucid, law-enforcement authorities argue, but quite sharp, very sane, and very much in control of a Manhattan-based crime family with franchise operations in the Bronx, in several suburban counties north of the city, and along the New Jersey waterfront. In other words, they say that the Chin is crazy like a fox.

His sick shtick, lawmen like to believe, is a ruse to avoid arrest, prosecution, and prison. The fact is, the Chin really may be demented, or possibly punch-drunk from his years as an amateur boxer. (His moniker is said to come from his pronounced jawbone, but a few cynics suggest that it goes back to his boxing days, when he often took it on the chin.) Psychiatrists have testified in court that he is also probably schizophrenic.

For all of his seeming incoherence, the Chin manages to discombobulate a large force of government agents, who have been trying to get him for thirtyone years, ever since May 1958, when they brought him to trial on charges that he had followed Vito Genovese's order and attempted to assassinate the late Frank Costello, who was then the prime minister of the underworld. The Chin was acquitted on insufficient evidence, but the incident doubtless hastened Costello's retirement and marked the ascension of Vito Genovese, the Chin's mentor and childhood neighbor, from whom the family that traces its lineage back to Charles "Lucky" Luciano takes its name.

Vincent Gigante is an organizedcrime survivor. One informer says Gigante climbed the ladder to the top spot as far back as 1981, sharing power with Genovese boss Anthony "Fat Tony" Salerno, who had suffered a stroke. By most accounts, however, Gigante's investiture as boss came in 1987.

New York's five crime families are on the defensive. Over the last two years, investigators have focused on high-profile John Gotti and the Gambino family, but the smaller Lucchese, Colombo, and Bonanno families have also been hurt. Within the Genovese family, a number of Gigante lieutenants have been bagged in suburban prosecutions. The Chin himself, however, continues to elude prosecution, and his weird behavior drives lawmen crazy.

"It is like a Howard Hughes syndrome," Ronald Goldstock, who heads New York's Organized Crime Task Force, told The New York Times. "He locks himself up in a small area, and it is hard to understand what enjoyment he gets from being a Mob boss. The only pleasure appears to be the pure power that he exercises."

Former F.B.I. agent John Pritchard, who headed a task force that tracked Gigante's movements for four years, told me, "He's as lucid as you and I. There's no question in my mind. He does oddball things, but the guy is not stupid."

In the course of his surveillance, Vincent Gigante was seen at times conferring with a priest, sometimes on the street, sometimes in his mother's apartment. Pritchard says that the discussions dealt with family matters and that they "never looked sinister."

The priest is Louis Gigante, Vincent's youngest brother. He insists that all the stories about Vincent are garbage, that the Chin is not a crime boss but just a poor victim whose mental condition has been deteriorating since the mid-1960s and who, in his mental disarray, provides law enforcement with an easy and defenseless scapegoat. "He's a mental case," says the priest, picturing Vincent as someone who can scarcely manage his own affairs, let alone a crime network. "Why don't they leave him alone? Vincent is ill. Vincent is in need of psychiatric treatment."

Louis Gigante is no simple, ordinary priest. On the contrary: he may be the most powerful street priest in New York, a doer and shaker who has spent over a quarter of a century in the dismal South Bronx and succeeded in resurrecting a part of it known as Hunts Point, where he has built a strategic hamlet of forty-five new and rehabilitated buildings containing nearly two thousand clean, airy, wellmanaged apartments. And despite a decade-long national retrenchment in government-aided housing, he has still more projects in the works. He served four years as a New York City councilman and headed his own political club. So it's no wonder that callers as diverse as Russian diplomats, Roman Catholic cardinals, and presidential candidates, including Governor Michael Dukakis on the eve of his 1988 campaign, have sought audiences with this priest.

He is not only a church power and a political power but also a community power, an urban hero, even, according to some of his admirers, an urban saint. But famous as he is for doing good, he is equally famous for being the Chin's brother, and the brother, too, of Mario and Ralph Gigante, who have been identified as lesser members of the Genovese family. Saint and sinners, God and the Godfather—Father Gigante has heard all the parables and he is outraged. He is convinced that government agencies are harassing a man who is a menace only to himself. Furthermore, he rejects law enforcement's theory that there is such a thing as a Mafia, or any single organized-crime network in this country composed largely of Italian-Americans.

In June of this year, Father Gigante made headlines when he put up $25,000 in bail money for one of the young defendants in the much-publicized gang assault on a woman jogger in Central Park. He said he did it, on his own volition and with his own money, because the boy's family couldn't raise the money, but for one whole weekend the tabloids and newscasters pointed their guns at the fifty-seven-year-old white-haired priest. In the sort of page-one headline it usually reserves for catastrophes at sea, the New York Post brayed: PRIEST BAILS OUT PARK PUNK. Inside, a second story was headlined "Man of the cloth's brother is reputed Genovese boss."

"When he came out of prison, 1964, Vincent was not the same," Father G. says.

Such reminders are not new to Father G., as he's known, and it was a bit ingenuous on his part to expect that his involvement with someone in a crime, however remote that involvement, would not bring forth a torrent of loaded references to this man of God and his brother the reputed Godfather.

As we talk in his plain, windowless office on 163rd Street, off Southern Boulevard and just beyond the Bruckner Expressway, he is still fuming over the endless references to Vincent in news accounts. "Who needs this shit?" he snaps, rattling a chair. It was just one more example, he complains, of the "media's overparticipation in people's lives to keep an issue alive."

I ask him if he resents the good-versus-evil notoriety. "In some ways, Vincent is a better man than me. He's got moral values sometimes much greater than I do." Later he says, "If a person is evil, God will deal with them."

We have three interviews, seven hours in all, mostly on his life and career and housing goals. But near the end of our last interview, he finally explodes, seeking to terminate once and for all the debate over a troubled brother under constant government scrutiny: "On Sullivan Street, they've made everyone paranoid. Cameras over there. F.B.I. agents looking out windows." His voice is rising. "For what? To capture this one man who is in a robe and who is ill, who has flights of sanity once in a while, who's taking this and taking that, who sees doctors three times a week. Suppose they get him off the street. Will that solve a crime?"

Part of his concern is purely personal. Louis Gigante is the keeper of the family flame. In Manhattan Supreme Court on February 16, defense lawyer Barry Slotnick submitted papers signed by Father G. to have the court appoint a conservator to handle Vincent's affairs and a guardian to care for him. In addition, Louis periodically takes his brother to St. Vincent's Hospital in Westchester County for psychiatric treatment.

There's clearly a risk to Vincent in this. "You think I'm stupid?" Louis asks me. "You don't think this guy's scared shitless because of the publicity, now that it's got out that the family has requested this?"

But it's a risk for the priest too, because it keeps the brother issue alive at a time when he has reached the apogee of his power and influence. Nine days before the bail incident, he had appeared at the sacred St. Patrick's residence of New York's John Cardinal O'Connor at the pleading of Mayor Koch. It was for an extraordinary summit meeting, and Father G. was at his combative, persuasive best.

The meeting had been called to resolve a dispute between the Koch administration and an activist ministers' coalition called South Bronx Churches. Among its members are some Catholic priests who are at odds with Gigante. The coalition was pressing Koch to abandon plans for a housing development in an area known as Site 404 in the South Bronx, on the periphery of Gigante's turf. Churches has its own housing ideas, and it would like to bypass the city's laborious bureaucratic process, which produced the Koch project. Churches argued that its plan was more efficient; the Koch people responded that theirs would yield more units per acre. But anyone familiar with the situation knew that this was a power struggle and that Koch was particularly vulnerable, given his tenuous standing in the election-year polls. Mayoral candidate Rudolph Giuliani had backed Churches at a slambang anti-Koch rally. The lines couldn't have been clearer: Koch versus Giuliani, priest against priest, and Cardinal O'Connor, who had made affordable housing one of his goals, caught in between.

In the end, thanks largely to Father Gigante, the Koch forces won out. During the tense meeting, he preached the virtues of form and process and argued that the administration's plan was already too far along to be halted. Ditching it now, he said, would open the way for lawsuits from architects and builders demanding their pay. Furthermore, the administration's plan would produce more housing than the rival plan, and besides, Churches was being offered other, if less desirable, sites in the same neighborhood. At one point Cardinal O'Connor, on his knees, urged unity and reconciliation. Finally, he rose and said, "I can't ask the mayor to go back to a process."

Leaving St. Patrick's and stepping out into the May sunshine; Father Gigante could well relish the moment. Not bad, as he would say, for a kid from the ghetto.

"Why don't they leave him alone? Vincent is ill. Vincent is in need of psychiatric treatment"

The Gigante boys were raised on the hard streets of an ethnic area within, yet somehow apart from, Greenwich Village. Yolanda and Salvatore Gigante arrived here from Naples in 1921 and settled in a cold-water flat on the top floor of a six-story tenement. In short order, they had six boys, one of whom died in infancy.

Salvatore worked as a watchmaker, and Yolanda got a job sewing in a factory. As the boys got older, she took work home at night to earn extra money, but that did not sit well with her Old World husband, who sold her sewing machine. ''I was angry a little," she recalled in a 1974 interview. "But don't you worry. I bought a secondhand machine for ten dollars. I worked day and night." She also did her best to interest her sons in the better things in life and to keep them from succumbing to the West Village streets' lure of machismo and fast money.

Louis did not succumb. Louis was different. He was bright and athletic. At Our Lady of Pompeii grade school, he came under the influence of a nun to whom he still writes in Rome, where she now lives. She urged him to enter the priest"I always remember wanting to be a priest," he says. But at the same time he was learning to play basketball on the West Side playgrounds, and he soon became a city all-star. At Cardinal Hayes High School on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx, Louis played well enough to win an athletic scholarship to Georgetown University. There the five-foot-ten defense-minded guard led the team to glory.

His finest moment came in 1953. Against rival Maryland, he held future N.B.A. scoring star and coach Gene Shue to eight points. "At halftime, Gene Shue, who ordinarily scores twenty-two to twenty-five points a game—at halftime he had nothing. ... I killed him," Louis Gigante recalls with a giggle. "Second half, he scored eight points. We won the game." Georgetown went on to the N.I.T. at Madison Square Garden and lost to Louisville. The next year, his senior year, Louis was sidelined most of the season with a broken leg.

He was a team player, not a great scorer, and a solid student, not an outstanding one. But whether on the court or in the classroom, he was known for his tenacity and leadership. He was a tiger. The summer after Georgetown, as friends expressed doubts that Louis would take the great leap into the priesthood, Gigante struggled with himself. "His girlfriend knew he wanted to be a priest," Yolanda remembered. "I prayed a lot for her. Now she's married and has four children." Finally the time to decide came, Gigante says, "and I knew."

He was ordained in 1959 and sent to Puerto Rico for two years. He still speaks fluent Spanish and delivers regular Sunday services in that language. Back in the States, he was assigned to St. James Church on Manhattan's Lower East Side, where he made his first headline by snuffing out a potential rumble. In 1962 he was assigned to St. Athanasius Church on Tiffany Street in the South Bronx. It was an important parish; one previous pastor, Terence Cooke, had gone on to become the cardinal of New York.

The parish, which is part of Hunts Point, a working-class community with a goodly percentage of middle-class Hispanics, was by then caught up in social upheaval. One block away was Fox Street, proclaimed by the new John Lindsay administration in City Hall to be the "worst block in New York City." Today, Father Gigante still feels the Lindsay administration compounded the neighborhood's misery by sending it its most troubled individuals. "They just dumped the worst welfare cases on us," he says.

All during the late sixties, the South Bronx was burning. Arson had become a form of social protest. Louis Gigante thought that a lot of the destruction was a reaction against poor housing conditions and an attempt by residents to get into the better-run public housing. Whatever the reason, the neighborhood was shriveling. The parish, once eight thousand in number, was down to two thousand by the mid-1970s. Worse still, in a period of limitless government spending to achieve the Great Society, precious little money was filtering down to Hunts Point. As it became clear that conventional missionary work would be inadequate to the task of restoring the area, the Reverend Louis Gigante decided that the moment had come for radical measures. He began to consider running for political office.

The Chin, meanwhile, was doing missionary work of a sort, too. Living in a series of walk-ups in the Village, he had hitched his star to his neighborhood idol, Vito Genovese, serving variously as his chauffeur, bodyguard, and gofer. In 1957, the Chin, already a veteran of the clubhouse boxing circuit, took his weight up to three hundred pounds. By design.

Joe Valachi, a Genovese soldier turned informer, alleged in The Valachi Papers, by Peter Maas, that Genovese, who was then second-in-command to the high-profile Frank Costello and ambitious to be on top, dispatched the Chin in May 1957 to rub out the prime minister. The prosecution maintained that Costello was surprised in the lobby of his Central Park West apartment building by an assailant who stepped out from behind a pillar, announced, "This is for you, Frank," and fired. Costello turned his head, and the bullet only grazed the right side of his scalp. The doorman described the fleeing assailant as a fat man, and police went looking for Vincent. According to Valachi, Gigante went into hiding "somewhere up in the country" and worked the weight off.

After returning to the city, Chin was arrested and stood trial. The doorman who witnessed the crime identified Gigante as Costello's assailant, but since the doorman was blind in one eye and had weak vision in the other, the jury considered his testimony untrustworthy. Costello maintained that he had not seen his attacker, even though Gigante's lawyer, Maurice Edelbaum, baited and badgered the prime minister with great theatricality: "You know who shot you. You know who pulled the trigger that night. Why don't you tell the jury who it was?" Costello would only reply, "Well, I'll ask you. Who shot me? I don't know."

Throughout the elevenday trial, which was chronicled in the Daily News, Yolanda Gigante sat in the back of the courtroom, reciting the Rosary. When the jury returned with a verdict of not guilty, she wept openly and cried, "It was the beads! It was the beads!"

According to Paul Williams, U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, as Costello prepared to retire, the Chin became a rising star in the Mafia world. Costello, however, had a surprise in store. According to several accounts, he successfully conspired with a number of the underworld's senior partners, Meyer Lansky and Carlo Gambino among them, to frame the overzealous Genovese and Gigante on a drug rap. Sentenced to fifteen years, Genovese died in the U.S. penitentiary in Atlanta in 1969. Sentenced to seven years, Gigante was out after five. But, according to Louis, the Vincent that emerged from the Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, penitentiary was already showing signs of mental illness.

"When he came out of prison, 1964, Vincent was not the same," Father G. says. "We think the combination of the fighting and the unjust fact that he went to prison—he went to prison for nothing he did—" brought on Vincent's mental decline. Authorities believe none of this. As far as they're concerned, 1964 was when Chin began his climb up the reconstituted Genovese family's corporate ladder.

In the Bronx, Louis Gigante reasoned that political office would give him access to the decision-makers, the planners, the grant and subsidy dispensers. So against Cardinal Cooke's wishes he ran for Congress in a tri-borough district that included parts of the Bronx, East Harlem, and Queens. Despite stumping in his collar, often accompanied by his mother and a nephew, he finished third. In 1973 he fared better, narrowly winning election to the City Council in roughly the same district.

His one term was uneventful, save for his support of a gay-rights bill in the face of church opposition. Though he chose not to run again, the experience changed his outlook. For one thing, he began wearing civilian clothes during the week, in particular a Yankee baseball cap. The council years also focused his attention on the question of housing—the inescapable need for it and the techniques for making it happen.

The Chin's own men have been caught on wiretaps referring to him as Aunt Julia.

"I went into housing to build a neighborhood," he says. "Church, God, Jesus Christ, and the neighborhood." Before you could minister to a person's spiritual needs, the priest had convinced himself, you had to tend to his need for shelter and stability. In 1968 he had formed SEBCO, the Southeast Bronx Community Organization, with leaders of twelve other organizations, but by the mid-1970s only five organizations remained. SEBCO had yet to produce anything. Then suddenly things changed.

All across America, the tax shelter came of age, and Gigante's SEBCO was among the first organizations to profit from it. Government-aided housing for the inner-city poor could also produce tax breaks for the wealthy. Louis Gigante and those around him felt that by producing the sites and applying for federal funding themselves they would be in a position to deal with builders not only eager to build but also eager to cash in on the tax-shelter craze. In other words, builders wanting sites were expected to cough up funds for the service, maintenance, and operation of organizations dominated by Father G. and the locals. "Cash flow" became the words of the moment.

Housing began to flourish in Hunts Point, and soon Gigante learned the fine art of screening tenants. It was possible not only to get good housing for parish members and local people but also to keep out troublemakers, social problems, alcoholics, and drug users. "His buildings look as good as the day they opened," says Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer.

While Louis was hunkering down on the hot streets of the Bronx, the Chin was finding relief in the cool shade of suburbia. He had married a dark-haired beauty named Olympia Grippa (known as Olympia I, in F.B.I. parlance, to distinguish her from Olympia Esposito), and their union would produce five children. In the mid-sixties they moved into a sprawling split-level house in Old Tappan, New Jersey, located in that part of Bergen County that has since been favored by Eddie Murphy, Brooke Shields, and Richard Nixon.

Even among the suburban gentry, Chin didn't change his stripes. On Christmas Day 1969, Olympia arrived at the local police station with "several hundred dollars" in cash for distribution to the five-man department. In the subsequent view of a Bergen County grand jury, this holiday largess was a payoff to the local cops in return for information on the workings of police surveillance outside Chin's home. The entire force was suspended. The charge did not stick, however, and all of the officers were reinstated. That was because Chin's family produced two psychiatrists, one of whom testified that Vincent was a schizophrenic and advised that consideration "should be given to the possibility of electro-shock."

Crazy or not, the Chin continued to climb, working under such bosses and overlords as Thomas Eboli, Frank "Funzi" Tieri, Jerry Catena, and "Fat Tony" Salerno until he reached the top. Louis Gigante, however, denies that any such progress ever occurred.

"Who's the boss now?" the priest asks rhetorically. "Oh, my brother! Well, how did you elect him? Who made him the boss? It's such a very, very enclosed situation. But say he dies tomorrow. What do they do?... They wait and listen to the eavesdropping and people talking that it's him, him, him, and they go around and say because he got more credit he must be the boss."

The money that is thrown into the war on the Mafia, he argues, could be better spent in the war on drugs and violence, particularly on the murderers who keep returning to the same stomping grounds. "What is the fear of this neighborhood?" he asks. "Certainly not the Genovese crime family. What is the fear of Sixty-eighth Street-andPark Avenue residents? Certainly not John Gotti. What is the fear? The fear of the promiscuous openness of drugs, prostitution, violence, and repeated criminals."

No one, it should be pointed out, has accused Louis Gigante of any organizedcrime involvement. He is indignant whenever the issue is raised. In a deposition given to the F.B.I. during an investigation of Morris Levy, the priest stated, "I am not involved with organized crime." Indeed, law-enforcement officials have repeatedly made it clear that Father Gigante is not considered a member or an associate of the Genovese organization. And in a well-publicized statement issued during a heated race for Bronx district attorney in 1988, then U.S. attorney Rudolph Giuliani called for the resignation of the incumbent, Paul Gentile, after Gentile accused Philip Foglia, his opponent in the race and the son of an officer of SEBCO Security Company, of leaking information about F.B.I. investigations into organized crime to one of his political supporters, the Reverend Louis Gigante.

Still, shadows have been cast. He has not been able to shake the whispers that he is a Mob priest, particularly after he played the role of a bishop who presides over a Mob funeral in Last Rites, a 1988 movie starring Tom Berenger. "If I have talked to people that may be questionable, there's no sin in that," he says. "We all do that." Many of these questionable types, like Morris Levy and Thomas Eboli, date back to his early years. In June 1971, when Joseph Colombo was gravely wounded during an Italian-American civil-rights rally in Columbus Circle to protest the F.B.I.'s characterizations of the Mafia, Gigante heard about the incident on his car radio and rushed to the hospital to administer last rites. In 1979 he served seven days in the Queens House of Detention rather than divulge the import of jailhouse talks he had had with gambler Jimmy Napoli several years earlier. It is, as he says, "no sin to talk to people."

Following a four-month investigation this past spring, The Village Voice alleged that some $50 million in SEBCO contracts had been funneled to construction firms with suspected ties to the Genovese family. In fact, many upright federal and city housing agencies have dealt with these same firms, because the Genovese family has long cornered elements of the city's construction industry. But because of the Chin's suspected role in the Bronx construction deals, the charges dog his brother far more than they ever would federal and city officials involved in housing.

Then there's the matter of life-style. Father Gigante is the first to say he never took a vow of poverty. He has a residence in Puerto Rico and spends much of his time in the summer at a country home near Albany. And he has reportedly earned $130,000 over the past two years from various SEBCO subsidiaries. Such revelations don't distress him nearly so much as the fact that people think a priest earning an income is unholy. After all, as he will tell you, he made a lot of investors rich. "You know what one guy said to me? He says, 'If those things are true about you bringing $50 million a year into this company, $200 million overall, you're worth $300,000 a year.' "

He lives a lot better than his brother Vincent, and his life is a lot more secure. New York's current cardinal leans heavily on this South Bronx priest for guidance. Last year, O'Connor came to Gigante's enclave for still another groundbreaking ceremony, this one for a pilot affordable-housing development for the archdiocese built to Gigante's specs.

"It would be very difficult to imagine what the South Bronx would have been without the efforts of Father Gigante," the cardinal said. "It would be hard to imagine the second spring that has come to the South Bronx without Father Gigante."

Louis Gigante started out as a missionary and ended up as a power broker in a beneficial sense. He made life better for a lot of people. If there is something besides bloodlines that he shares with his brother, it is that they both demonstrate in their own ways that a great city is run from the ground up.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now