Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMAMET MEETS MADONNA

Theater

David Mamet's new play takes on Hollywood

STEPHEN SCHIFF

Speed-the-Plow, David Mamet's first major play since Glengarry Glen Ross, swaggers onto the stage, chin up and ready to brawl. With his stiff brush cut and omnipresent cigar, Mamet himself has the air of a stubby bruiser (his friend and favorite actor, Joe Mantegna, calls him "Mr. Gung-Ho Tough Guy Who Always Knows the Answers"), and no other contemporary dramatist's works exude such pugnacity, such cock-of-the-walk confidence. When the curtain rises, his characters are already fuming and flexing, already poking at one another with the meanest, ugliest weapon at their disposal—Mametese.

His best plays start in medias res: in the middle of a world, a conversation, a language we don't instantly understand. Mamet refuses to translate. Instead of letting us languish at ringside, he shoves us right into the action, where the locutions fly fast and furious. Most playwrights—even the hip ones, like Sam Shepard and Lanford Wilson—draw us into the characters they've invented by whispering darkly about their pasts, their secrets. Mamet heaves all that out the window. His characters are what they utter, no more and no less, and the audience can enter them only by learning to think along with what they babble.

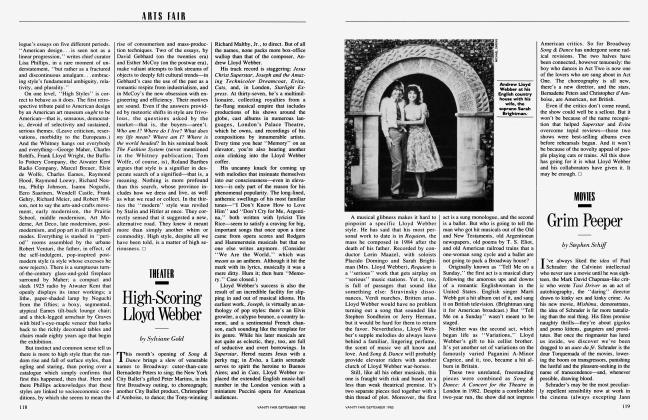

That gift of gab has served him best when he's used it to root among the underclasses of his native Chicago: the small-time thieves of American Buffalo or the real-estate hucksters of Glengarry Glen Ross—what Mamet calls "the bottom of the food chain." "David has pointed out that the language of the middle class has gone dead," says his friend and frequent director, Gregory Mosher. "There really is nothing to it anymore. Whereas you can still find, you know, cops and robbers who speak well." But in Speed-the-Plow, premiering at New York's Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater March 29 under Mosher's direction (it stars Joe Mantegna, Ron Silver, and Madonna), there are no cops and there are no robbers. No, the jabberwocky one hears at curtain rise is the oily schmoozing of Hollywood insiders at full throttle, wheedling, petting, and cajoling each other in search of the Golden Deal.

Speed-the-Plow's talk is as low-down and scabrous and realistic as anything Mamet has ever written, but it sounds utterly new—it has its own distinctive tang. The playwright doesn't stoop to the usual show-biz-isms: no one asks, "What's his back story?"; no one gives good phone. Instead, Mamet dives beneath the nonce words to get at the ageold patterns that produce them—the Yiddishisms, the raunch, the stroking and hand-holding and backstabbing. He's having fun here, and you can feel it. He knows how studio types sling movie references, so he makes up a few of his own, including such film icons as Balto the Sled Dog and Pancho the Dead Whale. He's also seen the way producers revel in the dirty thrill of selling their soul. "I'm a whore and I'm proud of it," a production chief exults. "But I'm a secure whore." And though Speedthe-Plow never mentions cocaine, one can almost hear the stuff caroming off his heroes' synapses as they extemporize about the mysterious industry that sustains them. Are they there to make wonderful movies? Are you kidding? "You wanna do something out here, it better be one of the Five Major Food Groups," says one. "Or your superiors go napsybye." Which, in its own concise and delirious way, just about sums it up.

'David has a fantastic sense of what's needed and what's not needed," says Mosher. "The principles for him are basically Aristotelian—that nothing should be in the story that doesn't belong, that everything in the play should move the story forward, that the play is an imitation of an action. From the first read-through of American Buffalo, he cut, I would guess, forty pages—of great shit, you know, just screamingly funny stuff. 'Why?' I said —it was the first time we'd worked together. He said, 'It's not necessary to the story.' " Speed-the-Plow's plot, too, is elegantly spare. A Hollywood producer, Charlie Fox, visits the new office of his pal Bobby Gould, who has just been promoted to head of production at some nameless studio. Fox has been toddling in Gould's footsteps—and lapping up his leavings—for years, but now he has his grubby mitts on something hot: the great Doug Brown (an actor? a director?) has fallen in love with a script Fox owns, and Fox has brought the project to Gould, who will "green-light" it and send it on to the studio boss for funding. Will the movie make money? "I think the operative concept is lots and lots," says Gould. Then sex raises its dangerous head. Gould has a new temp, an innocent cutie named Karen, and Fox bets him $500 that Gould can't get her to sleep with him. By Act Three, Karen has persuaded Gould to drop Fox's Doug Brown project and film instead a high-flown tome by some "Eastern Sissy Writer" about man's fate and the brevity of life and the end of the world and what it all has to do with radiation—in short, she has shattered Gould's smooth professional glaze by arousing in him the fiercest enemy of any successful studio boss: his artistic conscience.

(Continued on page 46)

(Continued from page 32)

Sound familiar? Naturally. Hollywood jeremiads are a dime a dozen. And yet Speed-the-Plow never feels stale; this isn't the usual bitter screed about cigar chompers brutalizing moist young poets and neurasthenic geniuses drowning the last whimpers of their talent in highlife and booze. Speed-the-Plow's characters are venal, small-minded, and, yes, monstrous, but they're also winningly vital, even exuberant—they've been galvanized by the peculiarly vivid lie they're living. If these are plowmen, they till their imaginary fields from speakerphones and swivel chairs, and the play is at its best conveying the vaporous, almost hallucinatory nature of their daily whirl. Mamet knows whereof he speaks. He did, after all, write the screenplays for Bob Rafelson's The Postman Always Rings Twice, Sidney Lumet's The Verdict, and Brian De Palma's The Untouchables, not to mention his own directorial debut. House of Games. And he's just finished directing his second picture, from a script he wrote with Shel Silverstein: it's a sweetish gangster comedy called Things Change, in which Don Ameche plays an old shoeshiner mistaken for a Mafia don. Mamet has strong reservations about Hollywood, but his attitude isn't unrelievedly bleak, the way David Rabe's was in Hurlyburly. Mamet kind of likes the place. Shocked at first by the puny stature accorded screenwriters in the Hollywood power structure, he soon learned to use his low-

"I'm a whore and I'm proud of it," a production chief exults in the play. "But I'm a secure whore."

ly niche to summon a new kind of discipline. "When you write a movie you're an employee," he has said, "and you have to deliver." And in Writing in Restaurants, his collection of mini-essays, he admits, "Working in the movies taught me (for the moment, anyway) to stick to the plot and not to cheat. . . . My work in a collaborative situation where I could not say 'It's perfect. Act it' was a healthy tonic."

In interviews and essays, Mamet often comes off as something of a scold, railing against the corruption of America's commerce and the debasement of her culture in terms neither enlightening nor particularly original. Shades of the beetle-browed moralist creep into the dramas too, but in Speed-the-Plow they're balanced by something close to tenderness. Like almost all of Mamet's plays, this one is finally about the ineluctable conflict between business and sentiment: Gould and Fox, like Don and Teach in American Buffalo or Danny and Bemie in Sexual Perversity in Chicago, would doubtless roll merrily toward fame and fortune if love didn't bung up the works. Yet as much as Mamet may rant in interviews about how "we've become so materialistic, so avaricious, that our capacity for love has become injured," Speed-the-Plow refuses to condemn its hopped-up hustlers. Gould, for instance, is plainly happier before Karen reinflates his withered scruples—and not just happier, but more alive, more energetic, more sane. And though the Doug Brown film he and Fox are planning will surely prove a lusterless piece of hackwork, the high-minded epic Karen wants him to make would almost certainly be worse—a mawkish disaster, aesthetically as well as financially. Mamet hasn't managed to make the sense of crisis as urgent in this play as in some of his previous work—there's no good reason why Gould can't make both films, for instance, or why Fox can't just take his project to another studio. But he's done something better. He's reached beyond the usual ain'tHollywood-awful story to get at the truth of the situation: that the movie culture is a calamity not because it's run by halfeducated reprobates who wouldn't know King Lear from Balto the Sled Dog, but because the system itself, the very field these overpaid plowmen tend, has become hopelessly inhospitable to risk, to valor, to real aspiration. A saint has no more chance of plucking beauty from it than a whore.

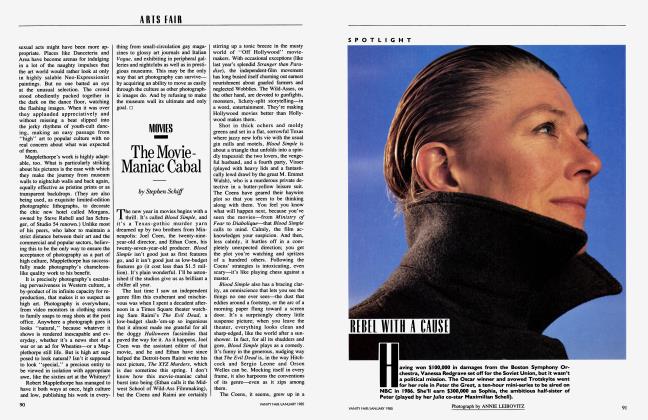

Mamet's ambivalence about Hollywood is exactly the sort of subtlety that a heavy-handed production could wipe out. So he's lucky to have such a sympathetic director and such a strangely apt cast. It's no surprise that Mamet and Mosher have selected Joe Mantegna to play Gould. And Ron Silver, who plays Fox, has by now portrayed so many Lotusland sharpies that some studio ought to make him an honorary V.P. What's startling is the choice of Madonna to play the purehearted naif Karen. "Joe and Ron I didn't audition," says Mosher. "I just knew they were the right guys. But Madonna—maybe we just liked seeing this Italian girl from the Midwest with this Italian boy from the Midwest. [Madonna was bom in Michigan; Mantegna hails from Chicago.] It's obviously a part that has nothing to do with brassiness and selling yourself. But the character does need the strength that it takes to be pure, and Madonna's strength just astonishes you when she walks in the room." That strength, in fact, may be exactly what the role requires. If Karen were portrayed as a darling little cuddle bunny, all sweetness and light, she could tip the play's delicate moral balance, and all the sympathy Gould and Fox should draw would drain to her side. So it may prove fortunate that Madonna's presence is always a bit forbidding, a bit inhuman—with any luck she'll turn Karen into a Joan of Arc with shorthand skills. And even if she fails, even if her stage debut proves she's not yet ready for prime time, her name on the marquee ought to keep Speed-the-Plow away from the halfprice window for a while. Which just goes to show, I suppose, that the theater, like the movie industry it so often decries, lives in a material world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now