Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHOW GENERAL ZIA WENT DOWN

EDWARD JAY EPSTEIN

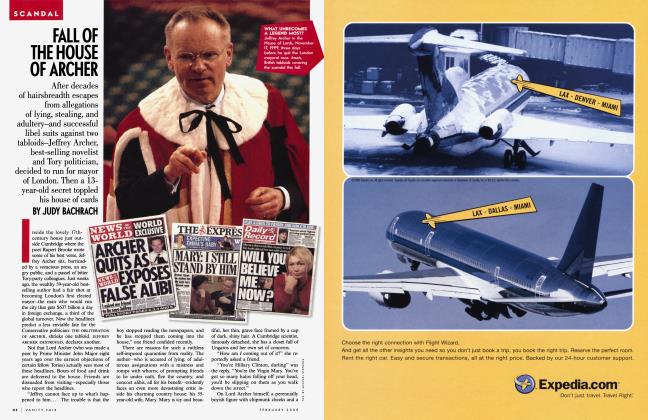

Investigation

What caused the mysterious crash? Who did it? And why was there a cover-up?

On August 17, 1988, Pak One, a C-130 Hercules transport plane, took off from the military air base outside of Bahawalpur, Pakistan, at 3:46 P.M., precisely on schedule. The passengers included Mohammad Zia ul-Haq, the army chief of staff and president of Pakistan, who was returning to the capital city of Islamabad after spending a hot, dusty afternoon watching a demonstration of the American Abrams tank.

This was General Zia's first trip on Pak One in two and a half months. He had reluctantly agreed to fly down to Bahawalpur that morning to see a lone tank fire off its cannon in the desert because Major General Mehmood Durrani, the commander of the armored corps and his former military secretary, was extraordinarily insistent in his phone calls. Durrani argued that the entire army command would be there that day, and implied that if Zia were absent it might be taken as a slight. As it turned out, though, the demonstration was a fiasco. The much-vaunted American tank missed its target. So much for the tank. Zia went on to lunch at the officers' mess, where he ate ice cream and joked with his top generals. Back at the airstrip, he knelt toward Mecca, and then, before reboarding the plane, warmly embraced those officers who were staying behind.

Seated next to him for the flight back to Islamabad was his close friend General Akhtar Abdul Rehman, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and, after Zia, the second-most-powerful man in Pakistan. He had headed Inter Services Intelligence (I.S.I.), Pakistan's equivalent of the C.I.A., for eight years, and had been the chief architect of the support system Zia had set up for the Afghan mujahideen, the Islamic opposition to the Communist government in Kabul. The I.S.I. had organized mujahideen into combat units, trained them, distributed weapons to them, provided them with intelligence, and even selected their targets. And now it seemed that the mujahideen were on the verge of winning. The Soviets were pulling out of Afghanistan.

Like Zia, Rehman had not wanted to come to the tank demonstration. Indeed, he had another appointment that day. He decided to go only when a former deputy of his at the I.S.I. advised him that Zia was on the verge of making major changes in the army and intelligence high command and suggested that his counsel was needed. So, canceling his appointment, Rehman had joined Zia on Pak One that morning. He reboarded the plane in the afternoon wearing his familiar peaked general's hat, accompanied by Lieutenant General Mian Mohammadd Afzaal, chief of the General Staff.

Zia and his two top generals sat in the front, V.I.P. section of an air-conditioned passenger "capsule" that had been rolled into the body of the C-130.

The remaining two seats in the section were given to Zia's American guests: Ambassador Arnold L. Raphel, an old Pakistan hand who had known Zia for twelve years, and General Herbert M. Wassom, the head of the U.S. military-aid mission to Pakistan. They had also witnessed the dismal tank demonstration, and afterward Ambassador Raphel paid a condolence call at a convent in Bahawalpur where an American nun had been murdered the week before.

Behind the V.I.P.'s, eight Pakistani generals packed the two benches in the rear section of the capsule. Lieutenant General Mirza Aslam Beg, the army's vice chief of staff, waved good-bye from the runway. He was the only top general in the chain of command not on Pak One that day. Zia had invited him aboard at the last moment, but Beg said he had a meeting scheduled at a stop on his way back home, and he boarded a small turbojet waiting to leave as soon as Pak One was airborne.

A Cessna security plane completed the final check of the area—a precaution routinely taken ever since terrorists had unsuccessfully fired a missile at Pak One six years earlier. Then the control tower gave Zia's plane the signal to take off. In the cockpit, which was separated from the capsule by a door and three steps, was the four-man flight crew. The pilot, Wing Commander Mash'hood Hassan, had been personally selected by Zia. The co-pilot, the navigator, and the engineer had been cleared by air-force security. Just the day before, the plane had been flown back and forth on a trial run between Islamabad and Bahawalpur to make sure there would be no surprises when Zia and his generals were on board.

After Pak One was airborne, a controller in the tower at Bahawalpur asked Mash'hood his position. Mash'hood radioed back, "Pak One, stand by,'' but then there was no further response. Those on the ground became alarmed, and efforts to contact Mash'hood quickly grew desperate. Pak One was missing only minutes after it had taken off.

Meanwhile, at a river about nine miles away from the airport, villagers looking up saw a plane lurching in the sky, as if it were on an invisible roller coaster. After its third loop, it plunged directly toward the desert, burying itself in the soil. It exploded and, as its fuel burned, became a ball of fire. All thirtyone people on board Pak One were dead. It was 3:51 P.M.

General Beg's turbojet circled over the burning wreckage for a moment, then headed for Islamabad. Beg radioed ahead to ask top army officers to meet him when he landed. With Zia and Rehman presumably dead, he, as the vice chief of staff, was now in command of the army. That evening, military units moved swiftly to cordon off official residences, government buildings, television stations, and other strategic locations in the capital.

What had happened to make Zia's plane fall from the sky? Benazir I Bhutto, the most prominent leader of the opposition, offered perhaps the most convenient explanation: divine intervention. In the epilogue to her recent autobiography, Daughter of Destiny, Bhutto notes that "Zia's death must have been an act of God.'' For he was, as far as she was concerned, the incarnation of evil. When she first met him, in January 1977, she had seen him only as a "short, nervous, ineffectual-looking man whose pomaded hair was parted in the middle and lacquered to his head.'' She could not understand why her father, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, then the prime minister, had picked him as head of the army. But in July of that year Zia seized power, and twenty-one months later committed "judicial murder,'' as she saw it, by hanging her father on a trumped-up charge. Zia consolidated his authority by pursuing a policy of "Islamization" and reinstating the law of the Koran, The thousand-year-old legal code existed side by side with an ultramodern military machine, complete with state-of-the-art F-16 fighters, guided missiles, and a scheme to develop nuclear arms.

Zia banned Bhutto's political party, the Pakistan People's Party, imprisoned her and her mother, and had both her brothers, Shah Nawaz and Mir Murtaza, tried and convicted of high crimes in ab- sentia. When Shah Nawaz died mysteriously in France in 1985, she suspected that he had been poisoned by Zia's agents. Zia had destroyed her family. She took particular satisfaction in the fact that his body was burned beyond recognition in the crash, noting that "Zia had exploited the name of Islam to such an extent people were saying that when he died, God didn't leave a trace of him."

But there also existed less divine sources of retribution. There was, for example, Mir Murtaza Bhutto. For the past nine years, Benazir's thirty-fouryear-old brother had headed an anti-Zia guerrilla group that shared offices with the P.L.O. in Kabul (and later operated out of Damascus). Called Al-Zulfikar, or "The Sword," the group was intent on destroying the Zia regime, and the means it used included sabotage, hijackings, and assassination. Al-Zulfikar demonstrated that it had the capacity to carry out complex international terrorist operations when it hijacked a Pakistan International Airlines Boeing 720 with a hundred passengers aboard in 1981. One of the passengers was executed in Kabul, and then the plane was flown to Damascus, where, with the assistance of the Syrian government, Al-Zulfikar forced Zia to exchange fifty-four political prisoners for the hostages.

Al-Zulfikar at first took credit for the destruction of Pak One, although subsequently, after it was announced that the American ambassador had died in the crash, they retracted the claim. But Mir Murtaza Bhutto admitted that he had attempted to assassinate Zia on five previous occasions. And one of these earlier efforts involved firing a surface-to-air missile at Pak One while Zia was aboard. On that occasion, the missile missed. Now, with elections called for the end of the year, and with his sister conceivably in a position to become prime minister if Zia were removed from power, Mir Murtaza had an added reason to pursue his mission.

He was not the only one with a motive. Another suspect was the Soviet Union. Earlier in August the Soviets had temporarily suspended troop withdrawals from Afghanistan to protest Zia's violations of the Geneva accords that had been signed in April. The Soviets claimed that Zia not only was continuing to arm the Afghan mujahideen in blatant disregard of the agreement but was directing the sabotage campaign in Kabul. After protesting to the Pakistani foreign minister, the Soviets took the extraordinary step of calling in the American ambassador to Moscow, Jack Matlock, and informing him that it intended to teach Zia a lesson.

The K.G.B. had trained, subsidized, and effectively run the Afghan intelligence service, WAD, which had in its campaign of covert bombings in the past year killed or wounded over 1,400 people in Pakistan, according to a State Department report released the week of the crash. Had Pak One been another of its targets? This seemed unlikely, given that the American ambassador was one of the victims. The Soviets would not have jeopardized detente by assassinating an American of that rank. But it turns out that neither Ambassador Raphel nor General Wassom was supposed to fly back on Zia's plane. At least until the day before the tank demonstration, both men had been scheduled to return on the U.S. military attache's jet (which General Wassom had flown down on). So the perpetrators might not necessarily have reckoned on an American presence aboard the plane.

The Soviet Union was not the only nation to have pointedly threatened Zia. In Delhi, Rajiv Gandhi, the prime minister of India, informed Pakistan on August 15 that it would have cause "to regret its behavior" in secretly supplying weapons to Sikh terrorists. The Sikhs were Gandhi's bloodiest problem. They had assassinated his mother when she was prime minister, and now there were some two thousand armed Sikh guerrillas entrenched in the country, mainly around the Pakistani border. According to Gandhi, Zia had been meeting with Sikh leaders and providing guerrillas with AK-47 assault rifles, rocket launchers, and sanctuary. In response, India had organized a special unit in its intelligence service, known as RAW, to deal with Pakistan.

It was not unlike Agatha Christie's thriller Murder on the Orient Express, in which, if one looked hard enough, everyone aboard the train had a motive for murder. Which was something that had not been lost on Zia. He was particularly uneasy about what might be done to undermine his power during the closing days of the Afghan war. In April, a huge arms depot for Afghan weapons had blown up in a suburb of Islamabad, killing at least ninety-three people. Zia blamed WAD for the blast, but Pakistani politicians criticized him and General Rehman for locating the depot where it endangered civilians. Zia reacted to an impending investigation by precipitately firing his prime minister, Mohammad Kahn Junejo, and dissolving the parliament. When Zia's eldest son, Ijaz ulHaq, a soft-spoken, impeccably dressed man now living in Bahrain, described to me how his father had been persuaded to go to the tank demonstration that day by his generals, despite his misgivings, and then General Rehman's sons told me how their father had been manipulated into going on the same plane, it raised the possibility that the assassination was the work of a faction in the army bent on pulling an invisible coup d'etat—a faction which knew Zia's movements.

It was not unlike Agatha Christie's thriller Murder on the Orient Express, in which everyone aboard the train had a motive for murder.

I here were clearly many people who would have been more than happy to see Zia dead. He had even offended the United States, although he considered himself America's greatest Asian ally. Zia was diverting a large share of the American weapons for the Afghan resistance to an extreme fundamentalist mujahideen group led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Not only was this group anti-American, but its strategy appeared to be aimed at dividing the rest of the resistance so that it could take over in Kabul—with Zia's support. American anxiety was also increasing over the progress Zia was making in building the first Islamic nuclear bomb. His clandestine efforts included attempts to smuggle the krytron triggering mechanism and other components for it out of the United States.

With Zia dead, the U.S. could foresee an amiable alternative: the replacement of the Zia dictatorship and all its Machiavellian intrigues by an elected government headed by the attractive, Harvardeducated Benazir Bhutto. In any case, the Americans seemed to have little interest in rocking the boat after the crash. Flying back from the funeral, just hours after the charred remains of Zia were buried, Secretary of State Shultz recommended that the F.B.I. keep out of Pakistan. Even though the agency had the statutory authority to investigate suspicious plane crashes involving American citizens, and its Counterterrorism Section had already assembled a team of forensic experts to search for evidence, it complied with the request.

The result was that the U.S. team assigned to Pakistan's official board of inquiry into the crash of Pak One included only six air-force accident investigators—and excluded any criminal, counterterrorist, or sabotage experts. An unrestricted investigation by the F.B.I. could have opened up a potential Pandora's box of geopolitical troubles. What if, for example, it pointed toward a superpower, a neighbor, or Pakistan's military itself? This could damage detente, leading to armed confrontation on Pakistan's borders, or even destabilize the shaky interim government in Islamabad. Why chance such uncontrollable consequences when the change in power could be attributed to an "accident" or "act of God"? So the State Department apparently decided to work to control the public's perception of what had caused the crash. Classified telegrams were circulated providing "press guidance" and advising that it was "essential that U.S. government spokespersons" stick to "proposed guidance before commenting to the media."

On October 14, a pre-emptive story was leaked to The New York Times headlined MALFUNCTION SEEN AS CAUSE OF ZIA CRASH. It began, "Experts sent to Pakistan. . . have concluded that the crash was caused by a malfunction in the aircraft." But on October 17, when the summary of the board of inquiry's report was officially released, the paper had to reverse itself. The headline now read, PAKISTAN POINTS TO SABOTAGE IN ZIA CRASH. The Times correctly reported that the board had concluded that "the accident was most probably caused through the perpetration of a criminal act or sabotage." But an unnamed administration spokesperson, presumably following official "press guidance," added that "the Pakistani findings were not the same as findings by American experts." The spokesperson even suggested a psychopathological explanation for the official report, saying that it reflected a "mind set" among Pakistani military officers who wanted instability so they had an excuse for continuing their military rule.

The problem with this press guidance was that it was misinformation. There was no such divergence between the American and Pakistani experts involved in the investigation, and no separate American conclusion of a "malfunction." Nor was it a conspiratorial Pakistani "mind set" that had ruled out a malfunction as the cause of the crash. This was the conclusion of the six American air-force experts, headed by Colonel Daniel E. Sowada, who formed the U.S. assistance and advisory team. They, not the Pakistanis, had actually written the sections of the report that led the board to state it had been "unable to substantiate a technical reason for the accident." This was confirmed to me by both the head of the investigating team in Pakistan and an American assistant secretary of defense. Colonel Sowada himself gave secret testimony before the House Subcommittee on Asian and Pacific Affairs that acknowledged that no evidence of a mechanical failure had been found.

The detective work of the investigators is contained in a red-bound 365page secret report, the relevant sections of which were read to me by a Pentagon official in his office. Like Sherlock Holmes, the investigators used a process of elimination. First, they were able to rule out the possibility that the plane had been blown up in midair. If it had exploded in this manner the pieces of the plane, which had different shapes and therefore different resistance to the wind, would have been strewn over a wide area—but that had not happened. By reassembling Pak One like a giant jigsaw puzzle, and scrutinizing with electron-microscope scanners the edges of each broken piece, they could establish that the plane had been intact when it hit the ground.

Nor had the plane been hit by a missile. That would have generated intense heat, which in turn would have melted the aluminum panels, and as the plane dived, the wind would have left telltale streaks in the molten metal. But there were no streaks on the panels. And no missile part or other ordnance was found near the crash site.

They could also rule out the possibility that there was an onboard fire while the plane was in the air, since if there had been one, the passengers would have breathed in soot before they died. Yet the single autopsy performed—on an American general seated in the capsule—showed that there was no soot in his trachea, indicating that he had died before, not after, the fire ignited by the crash.

The next possibility was that there had somehow been an engine failure. If this had happened, the propellers would not have been turning at their full torque when the plane crashed, which would have affected the way their blades curled and broke off on impact. But by examining the degree of curling on each broken propeller blade, the investigators determined that in fact the engines were running at full speed when the propellers hit the ground. They also ruled out the possibility of contaminated fuel by taking samples of the diesel fuel from the refueling truck, which had been impounded after the crash. And by analyzing the damaged fuel pumps, investigators could tell that they had been operating normally.

They deduced that the electric power on the plane had been working, because both electric clocks on board had stopped at the exact moment of impact, which matched precisely the time of the crash given by eyewitnesses and a computerized reconstruction of the short-lived flight. The crash had occurred, moreover, after a routine and safe takeoff in perfectly clear daytime weather. And the pilots were experienced with the C-130 and in good health. Since the plane was not in any critical phase of flight, such as takeoff or landing, where poor judgment on the part of the pilots could have resulted in the mishap, the investigators ruled out pilot error as a possible cause.

They thus came down to one final possibility of mechanical failure: that the controls did not work. But the C-130 Hercules had not one but three control systems. The two sets of hydraulic controls were backed up, in case of a leak of fluid in both of them, by a mechanical system of cables. If any one of these systems worked, the pilots would have been able to fly the plane. By comparing the position of the controls with the mechanisms in the hydraulic valves and the stabilizers in the tail of the plane, the investigators established that the control system was working when the plane crashed. This was confirmed by a computer simulation of the flight done by Lockheed, the builder of the C-130. The investigators also examined microscopically the mechanical parts of the controls to see if there were any signs of jamming or binding. The only abnormality they found, which led to a long separate appendix, was that there were brass particles contaminating the hydraulic fluid. Although they could not explain this contamination, they found that it could have accounted only for gradual wear and tear on the parts, not a sudden loss of control.

A gas capable of insidiously poisoning a whole flight crew had been used in neighboring Afghanistan.

Having ruled out all the mechanical malfunctions that could cause a C-130 to fall from the sky in the manner Pak One fell, the American team left it to the board to conclude that "the only other possible cause of the accident is the occurrence of a criminal act or sabotage leading to the loss of aircraft control."

This conclusion was reinforced when an analysis of chemicals found in the plane's wreckage discovered traces of pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN), an explosive commonly used by saboteurs, as well as antimony and sulfur. With these same chemicals, Pakistani ordnance experts reconstructed a low-level explosive detonator that could have been used to burst a flask the size of a soda can, which, the board suggested, could have contained an odorless poison gas that incapacitated the pilots.

But this was as far as the board of inquiry could go. No autopsies had been performed on the remains of the crew members to determine if they were poisoned. The report acknowledged that the board lacked the expertise to investigate criminal acts. What was needed was criminal investigators and interrogators. It therefore recommended that the task of finding the perpetrators be turned over to a competent agency, which meant, as one of the investigators explained to me, Pakistan's intelligence service—the I.S.I.

When I got to Pakistan in February and called upon Lieutenant General Hamid Gul, the director general of the I.S.I., I found that political events had apparently overtaken his mandate to investigate. He told me that at the request of the government the agency had called off its inquiry and had transferred the responsibility for it to a "broader-based" authority headed by a civil servant named F. K. Bandial. Mr. Bandial was not using the resources of the I.S.I., and, as far as Gul knew, the committee had not begun to work. General Gul's tone suggested that he did not expect any immediate resolution of the case.

But it was still possible to come to some reasonable conclusions about what happened to Pak One, if not the precise cause. A crucial piece missing from the puzzle was what had happened to the pilots during the final minutes of the flight. There was no black box or cockpit voice recorder on Pak One to recover, but there were three other planes in the area tuned to the same frequency for communications: General Beg's turbojet; Pak 379, the backup C-130 for Pak One; and the Cessna security plane that took off before Pak One to scout for terrorists. I managed to locate crew members of these planes—all of whom were well acquainted with the flight crew of Pak One and its procedures— who had heard the conversation between Pak One and the control tower in Bahawalpur. They independently described the same sequence of events. First, Pak One reported its estimated time of arrival in the capital. Then, when the control tower asked its position, it failed to respond. At the same time, Pak 379 was trying unsuccessfully to get in touch with Commander Mash'hood in Pak One to verify the plane's arrival time. They heard die words "stand by," but no message followed. When this silence persisted, the control tower got progressively more frantic in its efforts to make contact. Three or four minutes passed. Then a faint voice in Pak One called out "Mash'hood, Mash'hood."

One of the pilots overhearing this exchange, or lack of it, recognized the voice. It was that of Zia's military secretary, Brigadier General Najib Ahmed, who—apparently, from the faintness of his voice—was in the back of the flight deck (connected by a door to the passenger capsule). This meant that the radio was switched on and was picking up background sounds; in this sense, it was the next-best thing to a cockpit voice recorder. Under these circumstances, the long silence between "stand by" and the faint calls to Mash'hood, like the dog that didn't bark, was the relevant fact. Why wouldn't Mash'hood or the three other members of the flight crew speak if they were in trouble? The pilots aboard the other planes, who knew Mash'hood and were familiar with the procedures he was trained in, explained that if Pak One's crew were conscious and in trouble they would not under any circumstances have remained silent for this period of time. If there had been difficulties with the controls, Mash'hood would have instantly given the emergency "Mayday" signal. Even if he had for some reason chosen not to communicate with the control tower, he would have been heard shouting orders to his crew or alerting the passengers to prepare for an emergency landing. And if there had been an attempt at a hijacking in the cockpit or a scuffle between the pilots, it would also have been overheard. At the minimum, if the plane had been crashing toward earth, screams or groans would have been heard. The radio must have been working, since it picked up the brigadier's voice. In retrospect, the pilots had only one explanation for die prolonged silence: Mash'hood and the other crew members were either dead or unconscious, while the microphone had been kept open by the clenched hand of one of them on the thumb switch that operated it.

Tapes of the flight crew's last minutes may exist. One witness claimed that he had listened to such a tape after the crash to identify Mash'hood's voice, but the control-tower operators at Bahawalpur told me they had not made such a recording. They suggested that the main airport, at Multan, eighty miles away, could have tapes. (The U.S. National Security Agency might also have its own tapes, since, in what it calls "vacuum cleaning," it routinely sucks in radio and electronic signals from all parts of the world.) If such tapes exist, the clarity could possibly be enhanced to separate other background sounds from the static.

In any case, the accounts of the eyewitnesses at the crash site dovetail with the radio silence. They had seen, it will be recalled, the plane pitching up and down as if it were on a roller coaster. According to a C-130 expert I spoke to at Lockheed, the plane characteristically goes into a pattern known as a "phugoid" when no pilot is flying it. First, the nose of the unattended plane goes up, then a mechanism in the tail automatically overcorrects for this motion, causing the plane to head momentarily downward. Then, with no one at the controls, it would veer up again. Each swing would become more pronounced until the plane crashed. Analyzing the weight on the plane, and how it had been loaded, this expert estimated that Pak One would have made three rollercoaster turns before crashing, which is exactly what the witnesses reported. If the pilots had been conscious, they would have corrected the phugoid by adjusting the control column. Since this had not happened, he concluded— like the pilots in the other planes—that they were unconscious. He suggested that this could have been caused by a gas bomb planted in the air vent in the C-130, triggered to go off when pressurized air was fed into the cockpit.

My investigation at the Bahawalpur airport showed that planting a gas bomb on the plane that day would not have entailed any insurmountable problems. Instead of following prescribed procedures and flying to the nearby airport at Multan, where it could be guarded properly, Pak One had remained at the airstrip that day. According to one inspector there, a repair crew, which included civilians, had worked on adjusting the cargo door of Pak One for two hours that morning. Workers entered and left the plane without any sort of search. Any one of them could have dropped a gas bomb into an air vent.

I also spoke to an American chemicalwarfare expert about poison gases that could have been used. He explained that chemical agents capable of instantly knocking out a flight crew, while extremely difficult to obtain, are not beyond the reach of any intelligence service or underground group with connections to one. He also pointed out that a gas capable of insidiously poisoning a whole flight crew (and leaving the pilot's fingers locked on the radio switch) had been used in neighboring Afghanistan. According to the State Department's Special Report 98 on "Chemical Warfare in Southeast Asia and Afghanistan," corpses of rebel mujahideen guerrillas were found still holding their rifles in firing positions after being gassed. This showed that they had been the victims of "an extremely rapid-acting lethal chemical that is not detectable by normal senses and that causes no outward physiological responses before death." This gas, manufactured in the U.S.S.R., would have done the trick. But so would a host of other nerve gases. According to a technical expert at the U.S. Army chemical-warfare center in Aberdeen, Maryland, the Americanmanufactured VX nerve gas is odorless, easily transportable in liquid form, and a tiny quantity would be enough, when dispersed by a small explosion and inhaled, to cause paralysis and loss of speech within thirty seconds. According to the scientific expert, the residue it would leave behind would be phosphorus. And, as it turned out, the chemical analyses of debris from the cockpit showed heavy traces of phosphorus.

Such an act of sabotage would probably leave other detectable traces. The chemical agent that killed or paralyzed the pilots could probably be determined through an autopsy. If it was a sophisticated nerve gas, it had to be obtained from one of the few countries that manufacture it, transported across international borders, and packaged with a detonator and fuse mechanism into a bomb that would burst at the right moment after takeoff. All this could be traced back. In Pakistan, the device would have to have been delivered to an agent capable of planting it on Pak One at a military air base. And someone had to supply him with intelligence about Zia's movements, the operations of Pak One, and the gaps in its security. Since access to this sort of thing was limited to a few dozen people, whoever supplied the information would be vulnerable to discovery through an ordinary police investigation. Access to American intelligence resources, such as the technical labs of the F.B.I., the counterterrorist profiles of the C.I.A., and the electronic-eavesdropping archives of the National Security Agency, might also have helped locate the source of the intelligence (especially if it came in via telephones or a radio). But apparently no such determined investigation took place.

To begin with, as noted by the board of inquiry, autopsies were never performed on the bodies of the flight crew. The explanation for this, repeated to me by an official at the Pentagon, and apparently given in the secret report, was that Islamic custom requires burial within twenty-four hours. But this could not have been the real reason, since the bodies were not returned to their families for

burial until two days after the crash, as seven relatives confirmed to me. And, as I learned from a doctor for the Pakistan Air Force, Islamic law notwithstanding, autopsies are routinely done on pilots in cases of air crashes. I further determined from sources at the military hospital in Bahawalpur that parts of the victims' bodies had been brought there in plastic body bags from the crash site on the night of August 17, and stored, so that autopsies could be performed by a team of American and Pakistani pathologists. On the afternoon of August 18, however, before the pathologists were to arrive, the hospital received orders to return these plastic bags to the coffins for burial. The principal evidence of what happened to the pilots was thus buried.

The State Department apparently decided to work to control the public's perception of what had caused the crash.

The police investigation of those who had access to Pak One at the airport and were involved in its security also appears to have been curtailed. According to a security officer who was there that day, the ground personnel were not methodically questioned. Instead, they reported almost unanimously in interviews that they were amazed that no one was interrogated. The only inquiry they saw taking place was that of the American team. The questions by the Americans, which had to go through a Pakistani translator, were largely confined to the aircraft's maintenance and movements prior to takeoff. Other activities that day were not explored. For example, according to a police inspector at Bahawalpur, a policeman at the airstrip was found murdered shortly after the crash, but this was not investigated in relation to the crash or, for that matter, resolved.

Pakistani military authorities attempted to advance the theory that Shiite fanatics were responsible for the crash. Early in August, a Shiite leader had been assassinated, and some of his followers blamed Zia. The co-pilot of Pak One, Flight Lieutenant Sajid, was a Shiite (as are more than 10 percent of Pakistan's Muslims). The pilot of the backup C-130, who was also a Shiite, was arrested and kept in custody for more than two months while interrogators tried to make him confess that he had persuaded Sajid to crash Pak One in a suicide mission. He denied this charge even under torture, and insisted that, as far as he knew, Sajid was loyal to Zia. His interrogators abandoned their efforts to get him to talk after the air force demonstrated that it would have been physically impossible for the co-pilot alone to have caused a C-130 to crash in the way Pak One did. And if he had attempted to overpower the rest of the flight crew, the struggle certainly would have been heard over the radio.

The Shiite red-herring theory was only one of several efforts to limit the investigation into the crash and divert attention from the issue of sabotage. According to their families, records of phone calls made to Zia and Rehman just prior to the crash were destroyed. I.S.I. intelligence files on Mir Murtaza Bhutto are said to have disappeared. Military personnel who were at Bahawalpur at the time of the crash have been transferred. Taken together, these details add up to a well-organized cover-up. And if this is so, then the crash of Pak One has to have been an inside job. The K.G.B. or the Indian intelligence service might have had the motive, and even the means, to bring down the plane, but neither of them had the ability to stop planned autopsies at a military hospital in Pakistan, stifle interrogations, or, for that matter, keep the F.B.I. out of the picture. The same is true of anti-Zia undergrounds, such as Al-Zulfikar, although its agents, like the Shiites, could provide plausible suspects. Only powerful elements inside Pakistan had the means to orchestrate what happened both before and after the crash and to make the deaths of President Zia, General Rehman, and twenty-nine others look like something more legitimate than a coup d'etat.

But the eeriest aspect of this whole affair is the speed and effectiveness with which it was consigned to oblivion. Even though it involved the incineration of the principal ally of the U.S. in the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan, and the deaths of the American ambassador and the head of the U.S. military mission, there were no outcries for vengeance, no real effort to find the assassin. In Pakistan, Zia's and Rehman's names disappeared within days from television and newspapers. One no longer saw portraits of Zia, except for some still hanging in homes in Afghan refugee camps. In the U.S., the State Department blocked the F.B.I. from pursuing an investigation, and through "press guidance" distorted the event into just another air accident. No matter how well intentioned this cover-up might have been, the one uncounted casualty in the crash of Pak One was the truth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now