Sign In to Your Account

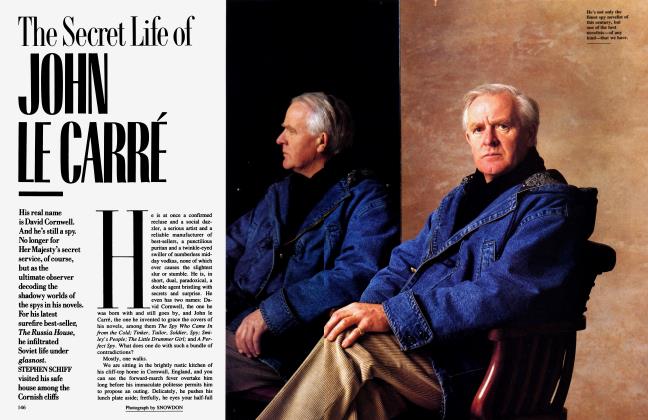

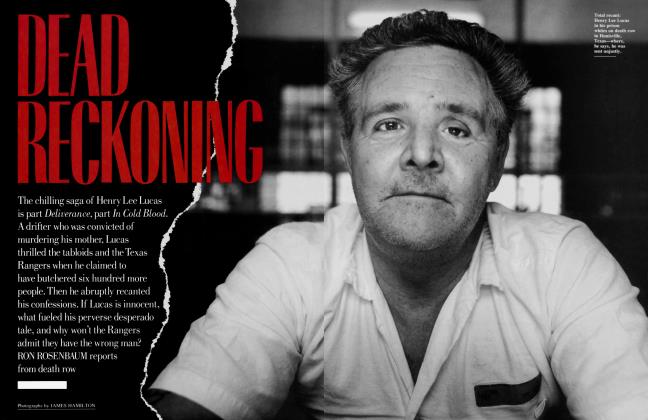

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

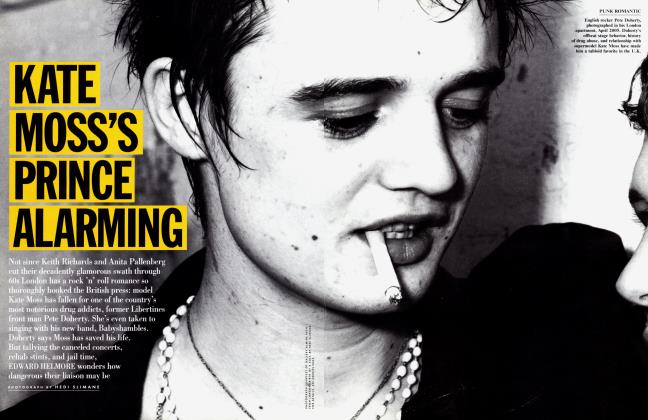

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowROTHWAX Here Comes the Judge

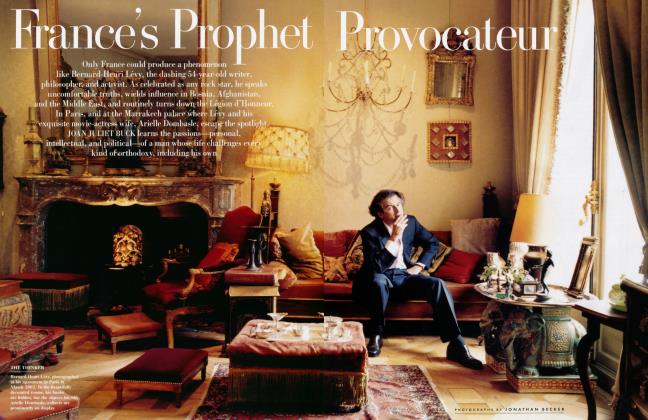

Something's wrong with the criminal-justice system, and Judge Harold Rothwax thinks he knows how to fix it. When he was a young defender of radicals, he used to see the defendant as the victim. Now, after seventeen years on the bench, he sees the victim as the victim— victimized again by the legal process. And he's angry enough to want to rethink the Bill of Rights. RON ROSENBAUM talks to the man who gave Joel Steinberg the max

RON ROSENBAUM

Okay, I admit it. I plead guilty. I was trying to provoke the judge. Because he's been a little bit too judicious with me so far. Judge Harold Rothwax was well known in criminaljustice circles as a brilliant, outspoken scourge of inefficiency, incompetence, and inadequate thinking about the legal system long before he attained national visibility as the trial judge in the Hedda Nussbaum/Joel Steinberg child-killing case. And while he's widely respected as a thinker, in the snake pit of the New York City criminal courts, where tough talk is cheap, Rothwax is most well known for the venomous tongue-lashings he'll deal out to dilatory and poorly prepared lawyers who have the bad luck to appear before him. His eloquent wrath has led some courthouse veterans to dub Rothwax the "Prince of Darkness,'' while awed observers who watched him hurl down rulings in the Steinberg case referred to him simply as "Yahweh,'' the Old Testament word for God.

But so far, in a series of conversations with me that began in his robing room off the Steinberg-trial courtroom while the jury was still deliberating, Rothwax has not unleashed his famous temper. He's delivered a number of provocative opinions that will outrage defense attorneys and civil libertarians, but he has delivered them in a goodnatured polemical style.

Tonight, in his Upper West Side apartment, I decided to see if I could get Rothwax to wax wroth. We'd walked back to his place after his Columbia Law School seminar to continue our discussion over a bite to eat. And there at his dining-room table I'd slipped him a clipping from a tabloid about a rapist and the extremely light sentence a local judge had given him. The rapist, a convicted murderer and con man, used a hooker friend to bait a trap for the naive victim, who was a virgin—until the con man and the hooker spent four hours raping and abusing her, using a metal object in a way you don't want to hear about.

He says he's not opposed to vengeance as a motive in sentencing. Vengeance can be a civilizing force.

But there were two surprises in the news clip I'd given Rothwax to read. The first was that the much-maligned New York City criminal-justice system worked like a Swiss watch in the case. The cops tracked down the con man and made the arrest. The D.A. got the hooker friend to flip over and testify against her pal. The jury believed her testimony and voted to convict. Then the presentencing investigation turned up a string of serious crimes, including murder, in the con man's past.

So here we have a vicious, murderous, recidivist career criminal guilty of the sex torture of a virgin. And then—this is the second surprise—the judge gives him just about the lightest sentence he could hand out, a shade above the minimum. With a little luck and good behavior the guy's back on the street in a couple of years.

As I watch Rothwax read through the clip, I can see I've succeeded in provoking him. First, he's shaking his head. Then, he's erupting into little snorts of disbelief. By the time he finishes reading I can almost see steam coming from his ears.

"I see you shaking your head," I say.

''I'm happy to discuss this with you freely," he says. "But I don't want to be in a position where I'm criticizing a colleague by name."

I agree to leave out the name.

"I mean, [the judge in question] is a jerk! His reasoning here is absolutely absurd. This guy [the rapist, not the judge] is a scam artist and there's every reason to believe that he does it on a regular basis. The record indicates an antisocial— He ought to have gotten the maximum sentence. It's outrageous!"

The fact that it was a scam crime makes it even worse. "I mean, you feel deceived. You feel tricked, you feel put upon—this should have been the maximum sentence and nothing less."

When we move on to the question of sentencing philosophy in general, Rothwax expresses some typically provocative, paradoxical takes on the question of retributive versus rehabilitative penology. He calls the rehabilitative philosophy favored by liberals "totalitarian, a kind of mind control," because it seeks subservience of mind from the prisoner (who is required to believe or mouth therapeutic pieties to parole boards and probation officers). While he believes old-fashioned "retributive" justice is not barbaric and vengeful but more "democratic" because it doesn't ask conformity of mind, merely incarceration of the body of the prisoner.

Was there something about the rape case that tapped into Rothwax's outrage at the administration of justice? Thinking about this question later, it occurred to me that the configuration of victim, crime, and punishment was almost an exact replication of the configuration at the heart of the famous opening scene of Coppola's Godfather. On the day of his daughter's wedding, Don Corleone is visited by a poor undertaker who tells him what happened to his young daughter.

She was raped and a judge has let the grinning perpetrators off with a slap on the wrist. It's that same twice-violated innocence. "I believed in America," the undertaker tells the Godfather, but "for justice we must go to Don Corleone." The message is clear: a collapse in confidence in the criminal-justice system will cause people to turn to criminals for justice. While Rothwax would undoubtedly disapprove of that solution, he's talking about the same problem.

The perception that the legal system is on the verge—or over the verge—of collapse is a fairly widespread one. It's there in the sudden surge of popularity of trash-TV "true crime" shows. America's Most Wanted deputizes its entire audience to bring justice to the victims of the uncaught criminals it spotlights. And the perception of collapse is there in Tom Wolfe's Bonfire of the Vanities, where the court system is a besieged and crumbling bastion half seized and sacked by vandals already, with only one choleric Jewish judge defying the barbarians on the battlements.

What's unusual about Rothwax's brand of judicial anger is that he started out as a liberal. A Brooklyn kid, he grew up tough and smart, the first son in a large family. Began supporting himself when he was seventeen with soda-jerk and busboy jobs. You can still see the Brooklyn streets, the defiant attitude toward pretension, in the defiantbut-disciplined wet-look pompadour he combs his now graying hair into. It's a look that says: I began combing my hair this way in Brooklyn forty years ago and until I see substantive evidence there's any reason I should change it, I won't. It suits the combative air he projects of a bantamweight fighter, a Jewish Jimmy Cagney.

The way he describes himself, he's always been embattled. "I was very outspoken," he's said of his childhood. ''I always fought authority. I did not take direction well or easily.

.. .It's a little ironic that as a judge I should be in a position of such authority—more power than any individual ought to have."

In the army too he got into scrapes with authority. ''In a way, I think I was inconsistently thinking I could combat the system, and yet live within it without sacrifice of principle," he says. ''The judgeship is very compatible with that—it may be the same dilemma."

What makes him an effective judge, Roth wax believes, now that he's part of the system, sworn to uphold it, is all that he learned as a criminal-defense lawyer about how to outwit and combat the system.

Starting in the late fifties, after graduating from law school at Columbia, he began earning a reputation as a topnotch criminal-defense specialist. Not the high-priced, hired-gun type, though. In fact, he proudly recalls, he never charged a client a fee. He started out representing the poor as a Legal Aid lawyer and went on to help found what would become a nationwide movement to bring free legal services to poor neighborhoods. New York's Lower East Side Mobilization for Youth was one of the few sixties/Great Societytype programs that not only worked but survived. What it did was expand the notion of legal services to the poor from representing clients when they got arrested for crimes to providing them with the same range of legal services available to the upper and middle classes.

''We'd often find that the reason this client came to us in trouble with the law could be traced to a whole series of legal problems—landlord-tenant, welfare or family disputes, disputes that if they could be dealt with would remove the circumstantial impetus to crime. We were trying to treat the whole body of our clients."

Although never a radical himself (he didn't oppose the Vietnam War), Rothwax ended up defending anti-war demonstrators, Black Panthers, Young Lords, and white protesters like Abbie Hoffman. He became a board member and even a vice chairman of the New York Civil Liberties Union. He concedes now he developed a perspective in which the defendant was the victim. ''Most of the defendants I represented were victims in one way or another. I mean, I knew all the things I could get away with as a defense lawyer in this system. No one knew it better than I did." He claims he got clients off on serious charges like attempted murder purely through assiduous use of delaying tactics that led to the charges being dropped.

But, he says, all that changed when he was appointed a criminal-court judge by Mayor John Lindsay in 1971. ''Before, I had been working to beat the system for my clients; now, when I became a judge, I used everything I d learned as a defense lawyer to defeat the very same tactics I'd used. It was my system now."

His perspective on victimhood shifted too—from the defendant as a victim to the victim as a victim. He saw the victims of crimes being victimized again by an inefficient, incompetently run criminal-justice system where justice delayed was justice denied. And delay, his sturdiest weapon as a defense lawyer, became the chief target of his wrath as a judge.

He's made his reputation as a judge as a slayer of delayers. Yes, he's a Columbia Law School professor who has a nationwide reputation for innovative practical and theoretical contributions to reform of the court system. But in the New York City-courts he's notorious for the characteristically Rothwaxian innovation he's introduced into the plea-bargaining process. An innovation that might be called The One Time OnlylBest Offer Up Front/TimedSelf-Destructing Plea Bargaining process.

(Continued on page 180)

(Continued from page 123)

Watching it in action can be a little shocking if one brings a Parnassian perspective to legal discourse in the New York City criminal courts. Indeed, a couple of hours ago at the opening of Rothwax's evening seminar at Columbia Law School, one of his third-year students, a diminutive young woman, boldly challenged the judge/professor over an instance of the One Time Only/Best Offer rule she'd seen in his courtroom a few days earlier.

"Would you explain to me," she asked, "why what went on there wasn't coercive?"

She was talking about a case that had come before Rothwax the week before. This case was kind of interesting in itself: twin-brother coke dealers. The dynamic duo was arrested in a blue Jaguar with Texas plates and charged with two sales of more than a quarter-pound each. The twins' cases had been separated—one had already gone to trial and been convicted. The other twin, for reasons relating to the nonidentical strengths of the cases against them, had been offered a deal before another judge six months earlier: plead guilty to a lesser felony and face a sentence of six years to life, or go to trial on the maximum count and face a minimum of fifteen years to life if convicted.

For six months that plea-bargain offer had been left on the table as, time after time, the case was postponed, delayed, held over before a more complacent judge than Rothwax. At last, for administrative reasons, the case came before him in his now part-time function as "calendar judge," where he'd made his reputation for speeding the disposition of cases with what might be called shotgun-marriage plea bargaining.

The way the law-school student described what happened was: "It was 3:15. You told the defendant he had fifteen minutes to accept the offer on the table, which was six years to life. If he didn't take it at 3:30 you were gonna take it off the table and it would never be available again and the minimum he'd be facing would be fifteen years to life. And fifteen minutes later the guy came back and said he'd take it."

Or, as Rothwax puts it, "In my courtroom it's best offer up front. You don't want it, fine. But then you have to realize you can't have it back. And you find out, if you tell a person he can't have it, then he wants it."

"This shocks you?" Rothwax asked the law student.

She nodded.

"You think it's coercive?"

She nodded again.

To explain why he believes what he did was not only just but judicious, however much it smacked of discount-appliancestore tactics ("We give you one low price for cash! We give you our best offer first!"), Rothwax launches into the mathematics of crime and punishment in New York City. Each year 125,000 new cases crowd into the Manhattan Criminal Court's calendar, 2,000 to 2,500 each week. But the courts can barely accommodate 2,000 trials a year. In fact, the maximum number of felony trials held has been 1,100, which means that ninety-nine out of one hundred criminal cases have to be substantially delayed if they're not settled before they come to trial—usually by plea bargaining.

This places a premium on settling a case before trial. "A guilty plea before trial also offers the state greater speed, finality, and certainty" than it would have if it depended on getting a unanimous jury verdict after an extended trial and no finality until after years of appeal.

"And so in return for his plea," Rothwax says, "we offer the defendant a discount on his sentence." It's a compromise, but to Rothwax it's preferable to endless drift and delay. The problem is that the plea-bargaining process itself can contribute to drift and delay. With the original judge's offer to the coke-dealer twin, "nothing had happened, and what do you expect? He left it on the table. There's no reason why [the accused] should take it now if it's gonna be on the table up to the moment of trial." It's this kind of plea bargaining that never produces a bargain.

But Rothwax's method is not coercive, he says. "It's inducement. Incentive to plead out. I think people should be told that their acts have consequences and that they're not living in a static universe. And that the real nature of what they're being offered is not a reflection of what they deserve but what the necessities of the system demand; that's why we give them a discount—they're serving certain purposes. If they don't serve those purposes, they shouldn't get the benefits of it. It shouldn't be an offer that lays on the table. I'm not defensive about that. It seems to me it's obvious. It's clear. It's up-front. Now, a lot of judges either don't understand or don't agree with that. I don't know why."

"Are you the only judge who uses this method?"

"When I was a calendar judge, I was, I think, probably the only judge that did it consistently. I don't think the others were temperamentally suited to it. But it always made sense to me and so I did it."

The Criminal Courts Building, 100 A Centre Street. This ancient, stained Dickensian edifice is the nerve center—or the brain tumor—of the criminal-justice system in New York County. The best of crimes, the worst of crimes in the city end up here. It's now the third day of jury deliberation in the Steinberg case, and the jury still seems hung up on the heaviest charge against the accused child-killer: second-degree murder.

Rothwax has agreed to talk to me while the jury is still deliberating as long as I don't ask him for any direct comment on the case itself. One of his court officers leads me through a dingy backstage corridor to a nine-by-twelve room just off the now empty trial scene. Aside from a couple of institutional chairs, the only fixture in the cell is a busted Bunn-O-Matic-type coffee-maker hot plate.

It's pretty depressing, and Rothwax could be waiting for jury notes in the carpeted, relatively plush by comparison comfort of his chambers several floors below. But that would mean delay, and this jury likes to send lots of notes. Shortly after we began talking, a court officer brought the latest in for Rothwax to unseal. It was a departure from previous notes asking him to repeat the legal meaning of "depraved indifference to life," etc. This was about scheduling dinner. The jury wanted to know if they could alter the schedule. Instead of going out for dinner at six and coming back to deliberate till ten, they wanted to deliberate straight through to eight, then go back to the airport hotel they were sequestered in and have dinner there.

After dealing with this crisis, Rothwax returns to telling me some of his provocative, controversial solutions to the larger criminal-justice crisis he's sitting in the midst of.

What's unusual about his solutions is that—unlike almost every other critic or reformer—he doesn't call for more of everything, more money for more jails, more judges, more courtrooms. He doesn't say the criminal-justice system can solve the problem of crime, but he does think the problems of the criminaljustice system itself are solvable, and not with more money but with smarter judges and smarter thinking. And rethinking: his most controversial suggestions—shocking, in fact, when you hear them coming from a former vice chairman of the New York Civil Liberties Union—are his calls for reconsidering certain sacrosanct Bill of Rights guarantees. For instance: the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination.

Next to the First Amendment freedoms of speech and press, the Fifth Amendment privilege against being forced to testify against oneself may be the most sacred text of the civil-liberties creed. Rothwax knows what he's about to say is a species of blasphemy—in fact, he claims he's going up against quasi-religious rather than rational objections. He says he "can't even get serious consideration" of his proposal from his law students.

"They're ready to question the existence of God and everything else, but when it comes to the Bill of Rights, it's like the first ten amendments are more important than the Ten Commandments. One we can reject, the other we can't question."

He concedes there are good historical reasons civil libertarians are attached to the Fifth Amendment—as a response to star-chamber, inquisitional abuses in which self-incriminating "confessions" were frequently obtained by coercion and torture. "It grew out of the rack and screw: 'Did you do it? No? Tighten up the screws. Did you do it? No? Tighten them again.' O.K., we're beyond that, but there's another, competing principle: that society is entitled to every man's evidence.

"Now, take the trial of [Z]." He names a controversial case over which he's presided, but asks me to leave out the name of the defendant, since it's a purely exemplary instance: "Z didn't take the stand. And I have to tell the jury that under the law it may draw no adverse inference from his not testifying. But here we've got a trial that has gone on for months. Obviously there is basis for believing that he may be guilty. Forget the rack and screw. Forget the police station where he's alone and the light is shining in his face. He's now in a courtroom, cameras are in the courtroom. The press is in the courtroom. The judge is there. What would be so wrong with a legal system that said, 'Now you've heard all the evidence against you, Mr. Z. Confer with your counsel and take the stand and tell us what you know. There will be no threats, no violence. Tell us your side of the case.' Why don't we have a right to this man's evidence?

"And what if he says, 'I don't want to do it'? Let's say he says, 'I want to keep my own counsel.' The judge should be able to say to the jury that his refusal to testify under these circumstances is a fact that they may consider weighing. Doesn't that comport with our understanding of the reality of the way people behave?"

Rothwax goes on to offer another variation on his version of the Fifth Amendment. This one might be called the "Sealed-Envelope Plan"—and it's even more heretical. It's a remedy, he says, for pre-trial "discovery" requirements that force the prosecution to make public, or turn over to the defense, all its evidence— and to subject its key witnesses to pre-trial examination. The result of all this pretrial airing and winnowing of the state's evidence, Rothwax says, has been to provide the crafty defendant with a "road map to perjury"—which allows him to thread his own testimony through the gaps and seams revealed ahead of time in the state's case.

Rothwax's solution: "Why not require a defendant to write down at the beginning of a trial, and put in a sealed envelope in the custody of the court, his story. Before all the hearings and discovery.

And then allow it to be unsealed only if he takes the stand at the trial. Merely for the purpose of discouraging perjury."

I am curious how far Rothwax's Bill of Rights iconoclasm goes. "Any other amendments you want to re-examine? What about Fourth Amendment searchand-seizure law?"

"Well, yeah, as a matter of fact," he says, "search and seizure is an area of expertise for me." And it turns out he's a stinging critic of the confusion Supreme Court rulings against illegal police searches have left behind.

Rothwax thinks things started to go awry in search-and-seizure law in 1961 when the landmark Supreme Court decision in Mapp v. Ohio prohibited the use of evidence that had been seized without a duly obtained search warrant. This prohibition has become known colorfully, almost biblically, as the "fruit of a poisoned tree" doctrine (one must not eat thereof).

Again, Rothwax professes to respect the historic origins of the Fourth Amendment—the ancient common-law principle that a man's home is his castle, and that he ought to be safe from the arbitrary intrusion of officers of the Crown, often bent on tyrannical ends.

But he claims the actual effect of the Mapp decision in the courts has been not to purify but to further poison the process.

"Mapp was intended to deter illegal police conduct," he says, "and it did in many respects, but one effect of it was merely to change police conduct." In practice, he claims, police still make illegal searches, but now they may just fib about it.

When he was a defense lawyer, he "got these law students to do a study of police testimony in search-and-seizure cases six months before Mapp and six months after it." The study focused on a big issue in drug cases: how much leeway do police have to search a suspect's pockets or his car for weapons and drugs? According to Rothwax, the study showed that before Mapp, cops tended to cheerfully testify they found contraband in a suspect's pockets. After Mapp, cops were suddenly, in extraordinary numbers, testifying that the suspects had taken the contraband out of their pockets and thrown it onto the ground in plain view of the officer. That is, no problematic search had been required at all, so the evidence could not possibly be the poisoned fruit of an "illegal search."

What's more, Rothwax says, subsequent Supreme Court rulings in the "poisoned tree" cases have been so hairsplittingly complex that it's become impossible even for a cop on the line who wants to make a good search to know where the line falls. "You end up suppressing highly reliable and appropriate evidence of guilt and there is a cost attached to that. Guilty people are going free. Let me give you an example of a case I actually had.

.. .It was a very simple case. Police officer alone in a radio patrol car. Midnight, high-crime arfea, he gets a call over his radio. Man with a gun at a particular location, walks with a limp, has red sneakers. Good police officer, turns on the key, goes. He's a block away. Within a few seconds, he's out of the car. He sees the man walking with the red sneakers and a limp. He fits the description. He gets out of his car. He pulls his gun. He says, 'Freeze.' He walks over to him. He pats him down and finds a gun in his rear pocket.

"Motion to suppress the gun as evidence comes before me as a [state] supreme-court judge, and I say, 'Motion to suppress denied.' It seems to me this is just what the police officer should have done. Either he does that, or he says I'm going for coffee. He wanted to respond to the radio report of the gun. He didn't respond with excessive force. To protect himself, he's right in drawing his own gun. He doesn't go up to him and start slugging him over the head. But the appellate division reversed me, three to two, on the grounds that the report of the gun came from an anonymous call. In other words, somebody called 911 and said there's a man with a gun down there. He didn't say who he was, how he knew it. The three judges who disagreed with me said it's an anonymous phone call, so it's unreliable. We don't know that we have an honest informant, you run the risk of police peijury—that kind of a thing. It goes to the court of appeals and the court of appeals sustains the reversal four to three. So you have thirteen judges who have passed on this, including me, and they're divided... seven to six against the cop's action. And they're doing it in reflection. They're doing it over time... over months with briefs and all the rest of that. Here's the cop on the street. There's no way this guy could know. I feel if I can't predict what's going to happen ... and I'm a professor and a judge... I've worked with this for thirty years— how can the cop know what to do?"

The remedy for this, Rothwax believes, is the "good faith" doctrine, which conservatives and an increasingly conservative Supreme Court majority have been pushing. The good-faith doctrine would allow the admission of evidence that was seized in inadvertent violation of the duly warranted process. Only intentional violations of due process—tfiose not in good faith—would result in evidence being suppressed. It seems minor, but it could make a major difference in the enforcement of gun and drug laws.

While I don't believe the ten amendments are more important than the Ten Commandments, I do think they are equally important—they say Thou Shalt Not to arbitrary state power—so I decided to run Rothwax's Bill of Rights revisionism by some top defense and civil-liberties figures. Alan Dershowitz, whose clients have ranged from Soviet dissidents to Claus von Btilow, was particularly incensed at Rothwax's contention that the Mapp decision encouraged police fibbing.

"Rothwax said that to you, but when was the last time he said that in court? Because Harold Rothwax is not prepared to stand up in court and tell people that policemen lie through their teeth, the Fourth Amendment is being abrogated. We had a case today in Massachusetts where a killer went free because cops admitted that they have a pattern of perjury in search-warrant cases, they have fake informants. It's particularly disturbing because Rothwax is such a decent man, such a bright man, that he's fallen prey to this rhetoric of righteousness that so many judges fall prey to.''

Dershowitz thinks Rothwax has been "on the bench too long,'' that he acted like a "second prosecutor" in the Steinberg case.

"If he just had the guts to stand up and be as tough to cops as he was to Steinberg, we'd have cops shuddering before bringing in tainted evidence and perjured testimony. Why aren't the cops required to put their story in a sealed envelope?"

Not that he buys the sealed-envelope revision of the Fifth Amendment privilege.

"None of what he's saying is so original. J. Edgar Hoover was saying this twenty-five to thirty years ago." He calls Rothwax's turn against the Bill of Rights a result of an "education in cynicism," the product of nearly two decades on the bench. Tampering with, undermining the Fifth Amendment is dangerous and shortsighted, Dershowitz says.

"We have good historical reasons for requiring the government to prove its case without the words of the defendant. That system has made us not only the fairest but also the most efficient and effective in the world in terms of determining the difference between guilt and innocence."

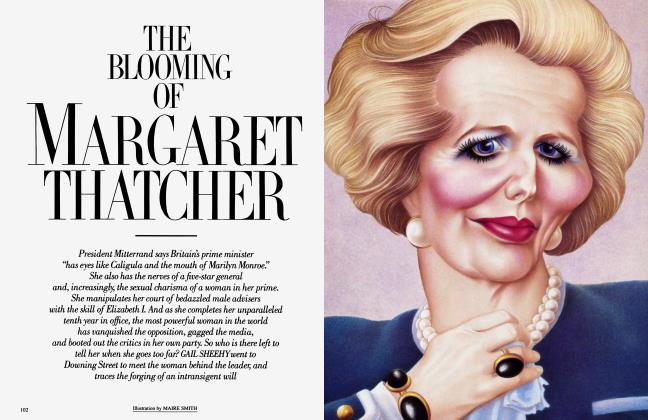

Nat Hentoff, Rothwax's former colleague on the board of the New York Civil Liberties Union, says he's "astonished that Harold Rothwax has apparently decided that the Bill of Rights doesn't work and that he wants to go to Maggie Thatcher's kind of justice." As for Rothwax's advocacy of the good-faith rule, Hentoff cites a recent University of Chicago Law Review study of the narcotics police. "The cops there all said, 'Thank God for this [Mapp] decision because it makes our cases stick.' Rothwax is a smart man, but this is a dumb approach to the exclusionary rule."

The question of good faith comes up in another context when Rothwax has harsh words for the bad faith of some criminal-defense lawyers, whom he doesn't shrink from condemning as "sleazy." He used the phrase "sleazy lawyers" fairly casually in his lawschool seminar, and I decided to ask him what kind of sleaziness he was talking about.

"We're talking about..." He pauses. "Sleaziness can be everything from bribery and perjury and corruption to willfully breaking the rules. It's a bugaboo of mine." The locus of sleaze these days, he says, is "a very complicated area" of the pre-trial evidentiary hearings in which an increasing number of cases are effectively decided by the amount of evidence defense lawyers succeed in suppressing.

"Criminal-procedure law says that if you want to move to suppress evidence you should submit an affidavit, a statement of facts, saying how your rights were infringed, and justifying your need for the relief that you've requested. Lawyers don't like to do that. Defense lawyers. They like not to have to say anything and get whatever they want. But I have been very strict in requiring that an affidavit be brought forward before a hearing is granted. A lot of the judges are not strict. You ask for die hearing, you get a hearing. They want to be nice guys. They don't want to create controversy, they don't want to be appealed. Judges are weak; judges are sloppy; judges want to be loved. Judges come up for reappointment, and defense lawyers have committees that review them. And judges may be lazy—whatever it may be. And it [sleaze] begins with that. And it grows."

Another "sleazy lawyer" problem he sees involves so-called Mob lawyers and "the kingpin problem." "For example," he says, "a Mafia kingpin and five other guys get arrested. Each lawyer is supposed to represent his client against the entire world, including his co-defendants. The Mafia kingpin hires a wealthy lawyer, and he says, 'You get five other lawyers for my boys.' So that lawyer brings in five other lawyers. Now, each lawyer is supposed to owe his total allegiance to his client, not to the lawyer who brought him in. But each lawyer [for an underling] knows that if he suggests to his client, 'If you cooperate, you could get a good deal for yourself,' and all the rest of that, that he'll be excluded from future referrals. And he won't do it. So that is something that's never discussed. And it is widespread. It's a problem."

The comments Rothwax makes about "judges who want to be loved" and the defense lawyers who review their appointments are a reminder of Rothwax's outsider status in the New York City judicial and legal establishment. Despite developing a reputation for a razor-sharp legal mind as a criminal-courts judge, despite being elevated to the state supreme court (which tries major felony cases), and despite being reappointed by Mario Cuomo, Rothwax still remains an "acting supreme-court justice," not a full-fledged one, because the nominating committees of the political-legal establishment have failed to designate him for the largely uncontested elections for full fourteen-year state-supreme-court terms. The reason may be that he has offended too many members of the politically active defense bar.

Nor is it likely he's ever going to get promoted to the appeals-court bench—not if the First Department of New York State's appellate division has anything to do with it. A couple of days after we spoke about the "sleazy lawyer" tactic of demanding evidentiary hearings, an unusual public feud broke out between Rothwax and the five appeals-court judges in the First Department over that very issue. APPEALS COURT FIRES LATEST SALVO AT ROTHWAX was the headline in Manhattan Lawyer. "A feud between... Rothwax and the Appellate Division escalated last month as the judge issued a rare public repudiation of a reversal."

In that reversal (of Rothwax's denial of an evidentiary hearing) "the Appellate Division went after Rothwax with a vengeance ... accused Rothwax of improperly denying the motion to bolster an appearance of efficiency in his court."

Rothwax hammered back at the appellate division in a letter published in the New York Law Journal. He attacked the higher court for "suggesting conscious wrongdoing" on his part: "I cannot or will not accept an unproved and unwarranted assumption that I am guilty of wrongdoing.... I suggest it is the Appellate Division that, in this instance, has acted inappropriately."

Embattled and defiant as his public stance is, in private Rothwax is a rather domesticated homebody. After his evening law-school seminar, I'd suggested continuing our conversation in a new Upper West Side bistro nearby. But Rothwax doesn't like to dine out. Instead, he led me to a deli, where we picked up beer and sandwiches and a quart of Breyers ice cream to bring home to his apartment. When we got to the modest but comfortable, quintessentially Upper West Side refuge, his wife (his second, they have two grown children) loaded up the Mr. Coffee, spread some place mats on the dining-room table, and left us alone with the tape recorder. Later, after we'd turned the tape off and were eating ice cream, she emerged and talked about her job as a school psychologist in East Harlem. As a therapist she's constantly dealing with the kind of underclass kids from broken homes and bad schools who may well—if they don't get help—show up in Rothwax's courtroom as criminal defendants. Each day she goes out and tries to deal with the sources of crime; he heads down to the Criminal Courts Building to face its effects. No wonder the two of them prefer staying home together to socializing and politicking. The old-fashioned serenity of their Upper West Side rooms is a precarious island of civility in the midst of a rising tide of disorder and decay, which they struggle with—Canute-like—every day.

Eight days have passed since the Steinberg jury came back with a firstdegree-manslaughter verdict, and Judge Rothwax has a problem. He's reluctant to speak about his problem, but it's there, an unspoken subtext of our conversations. Because the way he'll act on it, what decisions he'll make, will have an enormous effect on the public's perception of the legal system he cares about.

His problem, of course, is Joel Steinberg. More specifically, how heavy a sentence to hand out to Steinberg, who is probably the single most hated, universally loathed human in America at this moment. Already the public has been frustrated by the fact that Steinberg wasn't convicted of murder, but only of "manslaughter." The penalty for first-degree manslaughter in this case is up to the judge; it could range from a light 2 to 6 years to a fairly hefty 8½ to 25 years. Millions of people who saw the photos of pretty, smiling little Lisa Steinberg and then read about how she died will expect Rothwax to be the instrument not merely of justice but of vengeance.

When I raise the subject of his Steinberg problem and the public's desire for vengeance, Rothwax says he's not opposed to vengeance as a motive in sentencing. Vengeance can be a civilizing force, he believes.

"In pre-legal society, private vengeance was the norm. And the law took over by promising that it would do, in a civilized way, what private individuals had done in an erratic, disproportionate way."

He speaks of a paper written about his sentencing practice by a former law student.

"He called it something like 'Vengeance Has Gotten a Bad Name.' And it has, undeservedly. Not mindless vengeance. I don't mean that it should be a blind rage, whacking heads off. But criminal law is predicated on the idea that man is a moral agent, has the capacity to choose between right and wrong. And in that way it respects his personhood to punish him in retribution—it treats him as a responsible human being."

"What about making a public example of someone?" I ask. "I mean, there's a public revulsion at Steinberg."

"Yes, but I don't agree there ought to be a public example. I mean, from time to time we do that for deterrent purposes; we may arrest tax cheaters at tax time when people are filing their returns, and try to give them severe sentences. That doesn't bother me—it seems there is a clear deterrent impact from that. But the Steinberg crime is not deterrable."

"Why not deterrable?"

"People who abuse children I don't think are deterred especially by a heavy sentence. The emotional components, whatever they may be, are such that they're not following crime reports. And it seems to me that the retributive principle argues against that. Because basically it argues for equivalence between the act and the response, proportionality. And it would be wrong to give a disproportionately heavy sentence to a person simply to use him as an example."

On March 24, Judge Rothwax and Joel Steinberg both entered the eleventhfloor courtroom at 100 Centre Street for the sentencing ritual.

As Steinberg's new set of lawyers began to go through their pre-sentencing motions, I recalled something else Rothwax had said to me about sentencing. About the things convicted defendants say to judges in their final pleas for leniency. There was one thing Rothwax told me that he absolutely couldn't abide: a defendant who comes before him and says, "I made a mistake."

"That to me is a tip-off," he said. "I'm looking for a guy who says, 'I was wrong,' not 'I made a mistake,' like they're adding up a column of figures and they come up with the wrong sum. Criminal law doesn't deal with mistakes. It deals with wrongs, with people found consciously and intentionally doing the wrong thing. I'm not looking for a mistake. I don't buy a mistake."

Joel Steinberg's plea for leniency for himself (his lawyers had asked for a minimum two-to-six-year term because he was a first offender) was an astonishing twenty-minute monologue that can take its place beside the hunted child-murderer's final monologue in Fritz Lang's M for soul-chilling spectacles.

It was all a mistake, he insisted. The dead girl had been the happiest child on earth—everybody said so. It was a terrible mistake to call him a bad father. She'd been "well nourished, happy, healthy" in his care. Why, even the bruises on her skin the doctors noticed—he hadn't caused them. He'd never hit her. The bruises could have been caused by the emergency medical team trying to revive her and...

At this point Steinberg noticed something about Rothwax. The judge seemed to be laughing.

"I know Your Honor is laughing," he said.

"I'm not laughing. I'm just astonished," Rothwax corrected him.

But it was, in fact, a day in which the judge seemed to make little effort to hide his feelings. He appeared to treat the ineffective strategy of Steinberg's new legal team with contempt and sarcasm. Said their legal reasoning "verged on the bizarre and grotesque," battered them down brutally.

The judge "is like an electric wire today!" said Steinberg's now dismissed trial lawyer, Ira London, sounding greatly relieved at being out of range in a TV commentator's chair.

The most remarkable moment in the drama, however, came from the most restrained words Rothwax spoke all day. They came at the close of Steinberg's rambling it-was-all-a-mistake monologue. Well, it might not have been the close if Rothwax hadn't spoken up. Steinberg might have gone on forever. He was talking about how much care and affection he'd lavished on now dead Lisa. How her happy, healthy, carefree existence reflected the "constant nurturing, constant care, and constant love" that he, Joel Steinberg, perfect father, had given her. How her death was such a loss to him that he was the victim of the crime he was alleged to have committed.

At this point, Rothwax, in the softest, gentlest tones he'd used all day—indeed, in the softest, gentlest tone I'd ever heard him use—quietly inteijected: "Mr. Steinberg, you are beginning to repeat yourself somewhat."

There was no electric-wire jolt in those tones, but what happened was electrifying to watch. The moment Rothwax uttered them, Steinberg, who was standing for his plea, flinched, stopped talking, and half murmured, "Thank you, Judge," then crumpled back down into his seat. He sat silently, grimly awaiting what he knew was coming. And in fact Rothwax proceeded to hit him with the max—and more. In addition to sentencing Steinberg to the 8l/3-to-25-year maximum term, Rothwax added a strong recommendation against any parole, which guaranteed that, even with good behavior, Steinberg would be behind bars for seventeen years.

It was the harshest sentence he could possibly give in this case, but somehow those few soft words that crushed Steinberg back into his seat contained a more devastating judgment than any of the open electric-wire hostility he'd previously expressed. The sudden unwonted politeness, deference even—"Mr. Steinberg, you are beginning to repeat yourself somewhat"—was beyond anger, beyond contempt. It was the solemn politesse of the executioner.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now