Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

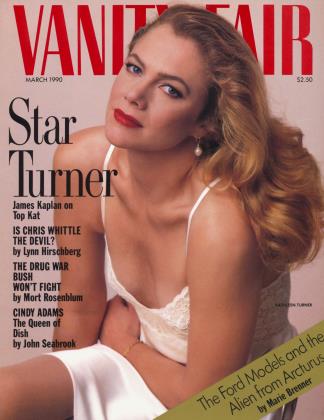

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSALZBURG SUPREMO

Gérard Mortier, a new kind of culture boss, will be calling the tunes in Karajan's kingdom

RUPERT CHRISTIANSEN

Music

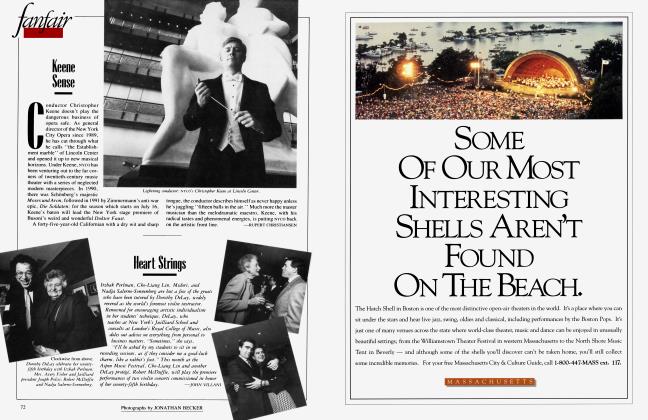

Brussels is a stuffy place, gray-souled, tight-assed. If you want glamour, passion, drama, or moral idealism there are trains, most hours, to Amsterdam, Paris, or farther south. Baudelaire went mad in Brussels. On one of the city's cobbled central squares, facing a row of garish shops and a concrete automobile underpass, stands the Theatre Royal de la Monnaie, a handsome neoclassical building with a raw postmodernist box of offices sitting on its roof. The Monnaie is the Belgians' national theater, and they are quite proud of it, even if they do not always subscribe to the goings-on there. It is not just another embarrassingly provincial arts center; it has a lustrous international reputation, due largely to the work of its director for the last ten years, one Gerard Mortier, fortysix and Flemish, and more than a little contemptuous of his homeland: "I want to hold a mirror up to my country, so that it can see itself and realize its own mediocrity," he announced in a recent interview. But the ambitious M. Mortier, who has in fact done very well by his country, is now moving on. Last August it was announced that he would succeed the late Herbert von Karajan as artistic supremo of the Salzburg Festival—a post he will take up in 1992 and which will elevate him to one of the key positions of power and influence in the Western musical world.

One of the most notable things about the Salzburg appointment is that Mortier is not a conductor, a creator, or any sort of performer or practitioner. Nor does he have Karajan's public profile. He is, simply, an exemplary specimen of a new breed of culture boss: the fixer, the executive producer, the administrator who, as a type, is increasingly usurping the prerogatives over casting, planning, and policy traditionally exercised by a musical or artistic director. Mortier long ago won the battle bitterly fought last year by Jane Hermann against Baryshnikov at American Ballet Theatre and by Pierre Berge against Barenboim at the Opera Bastille—a version of which is currently brewing between the board and James Levine at the Metropolitan in New York. As in the movie world, it's become the men with law or business degrees who are calling the tunes as well as paying the bills, leaving the notion of "artistic freedom" more a piety than a reality. "I do not interfere," says Mortier ambiguously, "but I am ready to take over if necessary"—a claim dramatically borne out by his recent screaming intervention into a chaotic rehearsal of Luc Bondy's production of L'Incoronazione di Poppea. "My fault is that I am trop passionne, too emotional," he sighs.

At the Monnaie, Mortier occupies a small white aerie at the end of a corridor known to habitues as "Fifth Avenue," a sly reference to what many consider to be the mecca of his ambitions. (One way or another, America is going to hear a lot about him, starting with the Monnaie's production of Mozart's La Finta Giardiniera, which he brings to the Brooklyn Academy of Music on March 15.) Mortier's office is fastidiously austere, appropriately enough for its occupant, who on first meeting seems almost absurdly ordinary. The successor to Karajan has all the charm of an overingratiating bank manager—the sort that just might give you the loan if you plead with him hard enough, and then just might not. Mortier is short, like Karajan, but there seems to be no other similarity. Until one notices his eyes. Behind the dense lenses of his spectacles they swivel and glare like the eyes of some exotic insect alerted to its prey. His energies are tightly coiled and sparingly, pointedly discharged.

The opera director Peter Sellars describes Mortier, entirely without malice, as "a little Napoleon who knows exactly what he wants to do, and then does it." He has an eighteen-hour-a-day schedule, which in his methodical way he is constantly running behind; even the Concorde has had to wait for Gerard Mortier. His staff seems to fear and admire him, but he is said not to be much liked. ''You're either his slave or his enemy," one of them complained. ''He's a control freak." Yet if his decisions have often been peremptory, they have rarely been the wrong ones.

Mortier's role model seems to be the extraordinary Rolf Liebermann, under whom he worked at the Paris Opera in the late 1970s.

Liebermann was a pioneer in ending the division of power that exists in a conventionally organized opera house between the artist and the administrator. Today there are several Liebermann-type figures on the European opera scene—Hugues Gall in Geneva and Brian McMaster at the Welsh National Opera, for example—and on their medium scale of operation they are producing more innovative and consistently successful work than the big international houses (La Scala, Covent Garden, Vienna), which are crippled by vast overheads, byzantine management structures, and a need to kowtow to the vagaries of seat-filling star singers. But Mortier is unique in his toughness, imagination, and downright wiliness. "I am Machiavellian," he admits. "I have to be. If you don't fight with the same weapons as your enemy, they will surely kill you." And then he smiles his suspiciously sweet smile.

Gérard Mortier was bom in Ghent in 1943, the only son of Flemish parents—and a member therefore of Belgium's subordinate class. His father was a baker, his mother a self-educated woman with a passion for music, to whom, until her recent death, he was extremely close. He was a Boy Scout leader and went to a Jesuit school, "oldfashioned, strict, and classical," where he picked up, by his own account, "charisma. Those priests showed me how to persuade others that you are right." From the age of eleven he was taken regularly by his mother to the local opera, and quickly became a connoisseur—the first record he bought was Callas's version of La Forza del Destino.

By the time Mortier went to college he was a confirmed opera fanatic with an encyclopedic knowledge of the genre, and his studies took second place to the running of a remarkable club, JeugdOpera. The point of Jeugd-Opera was neither amateur productions of The Mikado nor cut-rate bus trips to La Scala, but nothing less than a terrorist campaign against what was seen as the bland and mindless opera programming of the Belgian theaters. "They thought I was crazy to get so worked up about it," Mortier remembers. What they probably minded more was the club's activist wing, which pelted stages with rotten tomatoes and dropped pamphlets from the gods onto the heads of innocent Puccini-loving burghers sitting below. Jeugd-Opera's revolutionary manifesto was written by Mortier. It contains much of the same creed he maintained twenty-five years later in a sermonizing pamphlet he published as Par la Force de Chant, "Through the Power of Song," which earnestly defends opera's central role in the development of a society's intellectual and cultural life, and the way that, "through the magic power of song," it somehow links us to mythical archetypes.

Mortier's path from Belgium to Salzburg has been a straightforward one, and although he studied law "for the intellectual self-discipline," the forza of his destino as an opera administrator has never been much in doubt. (He also studied "Media and Communications Sciences" in the U.S.—a fact that for some reason he is reluctant to advertise but that perhaps explains his subsequent masterly handling of the Belgian press.) Having been launched by the patronage of Jan Briars, a godfather figure in the Belgian musical world, into a job at the Flanders Festival, he spent the 1970s sailing his way through an apprenticeship in the planning departments of major opera houses in Diisseldorf, Frankfurt, Hamburg, and Liebermann's Paris. "I discovered a talent for convincing singers to try new roles," he says. "It was I who gave Hildegard Behrens her first big chance as Katya Kabanova. It was I who told Eva Marton that she was a young Rysanek, and that she should leave the Italian repertory alone."

All of which is probably true.

Mortier occasionally allows himself to be charmed by a bit of American wackiness.

With gifts like that, it wasn't long before someone gave Mortier his head, and his appointment in 1981 to the directorship of the Monnaie, then in an operatic trough, was inevitable. It was also politically mined. The post is controlled by the government, a delicately balanced coalition, and has traditionally been allotted to someone from the French-speaking community.. The Flemish Mortier has thus enjoyed the overall support of the Flemish-dominated Catholic-Socialist alliance, and the overall hostility of the French-dominated Liberal Party. The opposition's line of attack has invariably been financial. In his first years Mortier authorized a lavish restoration of the charming but primitive theater, the result being a superb range of technical facilities and a spectacularly beautiful foyer. (The black-andwhite geometrically tiled floor designed by Sol Le Witt offsets a ceiling splattered with primary colors by Sam Francis—neither of them much loved by your average Bruxellois.) All of this was expensive; Mortier, in fact, was blowing wads.

In 1985, Mortier made the first of several threats to quit if grants did not increase, and his parliamentary supporters, thrilled by the Monnaie's rise to international prestige, voted more subsidy money. But the promised sums never materialized, and the Monnaie sank inexorably into the deep, dark red. The government then instituted a confidential inquiry that reported unfavorably on Mortier's financial management—news that a member of the hostile Liberal Party leaked to the press. Mortier handled his humiliation with characteristic vulpine cunning, lobbying relentlessly and publicly pointing an accusatory finger at other targets. Although forced to accept a measure of direct financial supervision, he won the battle. He was getting results that made him too good to lose.

This episode was swiftly followed by a rift with the Monnaie's resident choreographer, Maurice Bejart, who was (and still is) enormously popular in Belgium. Bejart, a symbol of the French community's cultural dominance, bit his lip as Mortier, who has little interest in dance but knew that he disliked Bejart's pretentiously vulgar ballet spectacles, turned the Monnaie's resources more toward opera. Then in June 1987, after what one commentator describes as a mudslinging querelle des concierges, again over money, Bejart took himself and his sixty-member troupe off in a huff to Lausanne, ending a twentyseven-year relationship with the Belgians and creating an international scandal.

Barely ten days later, Mortier was in Stuttgart to see Peter Sellars, who told him to go to a performance of the Mark Morris dance group, which happened to be in town. Morris was working with Sellars on the opera Nixon in China, and the two enfants terribles of American culture had become close friends. Mortier had never so much as heard of Morris before, but at dinner after the show he was sufficiently impressed to offer him Bejart's place at the Monnaie, with a three-year contract. "It was an incredible deal that we would have been mad to refuse," says Barry Alterman, the group's general manager. Instead of the hand-to-mouth frustrations of U.S. arts funding, here were the security of a base, the use of a sophisticated theater, its rehearsal studios and orchestra, as well as the chance to double the number of dancers in the company. The deal also suited Mortier, providing him with a ready-made product—cheaper than Bejart's circus—which he thought he could fit into the Monnaie without affecting the delicate French-Flemish political seesaw, Perhaps another factor was that Morris's work was the antithesis of everything Mortier deplores about the insular bourgeois sensibility of the Belgians. And Morris himself appeared to be the sort of wild child that Mortier likes to adopt, patronize, and educate. "Under my tutelage," he has been heard to say, "Mark has matured into an adult human being."

But the success of Morris's first eighteen months in Brussels has been mixed. American and British critics review his work as masterpieces and moan about how lack of financial support in the U.S. prevents the country's most talented people from working there with decent resources. In Brussels, the response has been less unanimously favorable. The city doesn't seem to have provided Morris with an audience capable of understanding him. If the dazzling Baroque prettiness of Handel's L'Allegro, il Penseroso, ed il Moderato went down well enough, Dido and Aeneas (in which Morris, for all intents and purposes the director of the Belgian national dance company, played the heroine, in a dress) was called "a cheap drag show." The premiere of Mythologies, which included a striptease that ended with the dancers naked, provoked a front-page headLINE-MARK MORRIS GO home—in Belgium's most powerful newspaper, Le Soir. Mortier has been publicly loyal to his import, but he has privately shown signs of irritation at his waywardness. What probably matters most, however, is the enormous amount of international coverage the theater has received. And in fact Morris will be heading home before Mortier heads to Salzburg.

"Perhaps Mr. Levine has made a mistake in staying at the Met so long" Mortier says, smiling sweetly.

Peter Sellars calls Mortier "the best opera producer in the world," the best fixer, with the best taste. Pierre Audi, artistic director of the Netherlands Opera, compares his gift for combining creative talents to that of Diaghilev. And one assumes that somebody in Salzburg must agree with them. But what precisely did he do at the Monnaie to deserve these accolades? Apart from masterminding the physical restoration of the house, he has built up a first-class orchestra and chorus out of what ten years ago was considered a national disgrace. His collaborator in this department has been Sylvain Cambreling, the Mbnnaie's chief conductor and a close friend, whose home in Brussels he has shared for several years. In his choice of directors he has struck a balance between conservatism and experiment, attracting many famous names—Chereau, Stein, Berghaus—as well as developing lesser-known talents. "In principle, I prefer classical elegance to brutal ism," he says, but he occasionally allows himself to be charmed—as in the cases of Morris and Sellars—by a bit of American wackiness. His casting is rigorous, and his eyes are not starry. "My public knows that the doors of the Monnaie are too small for Pavarotti, the corridors too narrow for Jessye Norman," he proclaims, and he has defiantly struck out against the insanely inflated levels of certain singers' fees. Mortier's Monnaie has had its failures, but it never sinks to the routine trundling that bedevils New York or Vienna.

The strength, and perhaps the weakness, of Mortier's aesthetic is its intense seriousness. His tastes, much influenced in recent years by his association with Cambreling, are puritanical and exclusive. Puccini, Massenet, Donizetti, and Richard Strauss (apart from Salome and Elektra) all suffer his implacable thumbs-down. "// n'a pas le sens de la fete," a friend remarks wryly. He's not really a good-time kind of guy.

With all this Jesuitical sense of the absolute comes an uncompromising management style. He arrogates power, finding it difficult to delegate and needing compulsively to know everything about everything and everybody. His favoritism is open. Prot6g6s of the moment are generously rewarded, those who fall from grace are not given a second chance. Women at the Monnaie have complained that they lack opportunities for advancement and that goodlooking young men find promotion easier. Mortier's appointment last fall of an inexperienced twenty-three-year-old to the post of his personal assistant has caused considerable resentment. A remarkably high percentage of his employees are under thirty. Bright kids come cheaper and more malleable than seasoned pros with wills of their own.

Mortier has deployed the Machiavellian tactic of divide and rule in masterly fashion. The Monnaie has become a stronghold of Flemish speakers, but he refuses to commit himself to any party or faction. He never turns down a chance to speak on television, and he assiduously cultivates his allies in the media with freebies and exclusives. His friends include a number of usefully rich elderly ladies, such as Dora Janssens, the pharmaceuticals heiress, to whom he graciously gives his arm.

In Salzburg, Mortier will have to adjust himself to a new game. He is inheriting a court and a protocol from a longreigning absolute monarch whose legacy is problematic. Even if what he wants is really a "soft revolution," he will have to restructure the festival's financial base to compensate for the loss of the complex deals with Recording companies that Karajan used to underwrite his Salzburg activities. And the economics of the festival will hardly be his only problem. Already there is vocal opposition to change from Karajan's supporters among the Austrian haut monde and sections of the merciless Viennese press. The influential Franz Endler of the Kurier has already made it clear that he believes Mortier's proposals are "too radical, and perhaps not so interesting." But "I am armed for all that by Brussels," retorts Mortier. "I don't care so much." More worrying is the bamlike Festspielhaus itself, a monstrous and ugly auditorium with a vast stage quite unsuited to Mozart, which is, after all, supposed to be the festival's chief concern. "We are studying ways of reducing the proscenium and making the space seem more intimate," he says. "But I admit that it is a problem. Salzburg has no satisfactory theater for opera, and very poor rehearsal facilities."

As to his more specific plans, he is cagey—perhaps because he is in the, for him, unaccustomed position of having to function as part of a triumvirate, consisting of himself, an administrative and a financial director (there will be no music director, although Solti will have some sort of consultancy). But he is clearly determined to remake Salzburg as "the intellectual and cultural center of Europe, a pivotal point for East and West, North and South, which it is geographically positioned to be. Opera there will meet other art forms. We might play Les Troyens of Berlioz alongside The Trojan Women of Euripides." He is equally determined to abandon Karajan's overupholstered all-star luxury jamborees. "I have to convince this audience that you do not need Domingo or Madame Te Kanawa for a great operatic experience. The composer must again become more important than the interpreter." He wants to import directors like Stein, Chereau, and Sellars, and to open up the place to "early music" conductors like Harnoncourt, whom Karajan excluded. His extraordinary run of success at the Monnaie in developing a lean and lucid style of presentation for Mozart operas seems to have been the crucial factor in his appointment to the festival, and he shows no interest in his predecessor's penchant for the Italian pops. "I see no reason to play Tosca in Salzburg. It is irrelevant. Instead, I want the twentiethcentury classics, the operas of Debussy, Berg, Janadek, and Stravinsky, to establish themselves there."

"You're either his slave or his enemy," one of his staff complained.

"He's a control freak"

It amounts to an immense and in many respects unenviable challenge, but Mortier doesn't mind a fight. He will even tell you that he sees his looming six-year sojourn in Salzburg as a sort of sabbatical. "There will be time for rest, for intellectual refreshment, solitude,"

he says, although it is more likely that he will be busily plotting his next move. Five years ago Mortier spent several months doubling his directorship of the Monnaie with that of planning the Bastille project in Paris, quitting abruptly when Jack Lang, the French minister of culture, refused to implement his tough proposals for curbing the stranglehold of the unions on work practices. Now he confesses to thinking more about America. "Perhaps Mr. Levine has made a mistake in staying at the Met so long," he says, smiling sweetly again. "They have never offered me anything, but I would like one day to have an opera house in the States—such openness to novelty and such a lot for me to do!" In an interview this fall he acknowledged discussing a future position ("in 1993") at the Met, presumably when the board there is able to come to terms with the relationship between the general manager and the artistic director. That Mortier's debut in America, with La Finta Giardiniera, should be a big success matters a lot to him. And Karl-Emst and Ursel Hermann's production should get a lot of attention. Neither Romantic nor rococo, untrammeled by either design chic or the posturings of star singers, it is Mozart scrubbed clean without being sterilized. Meanwhile, the Monnaie has become one of the co-producers of John Adams's new opera about the Achille Lauro incident, to be directed by Sellars, choreographed by Morris, and toured around the U.S. and Europe in 1991-92, Mortier, in short, is about to establish himself as a player on the American scene, although perhaps not in exactly the way he intended, as a recent attack on him by the chief music critic of The New York Times suggests.

In Brussels, Mortier will go out, in appropriately apocalyptic fashion, with a new production of the Ring by Herbert Wernicke. His success on the next stage of his travels is by no means ensured, although outside Austria he has many well-wishers. His old friend the conductor Christoph von Dohnanyi, for one, feels that he is the festival's best hope: "Change in Salzburg is long overdue, and Mortier is not afraid of it. He never compromises, never pulls back." Yet that very intransigence could easily tell against him, and for all his canniness he may have underestimated the poison latent in Karajan's legacy. Maybe Mortier really is the Napoleon of the opera world today—a long way from his Saint Helena, but not, conceivably, so far from his Moscow.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now