Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

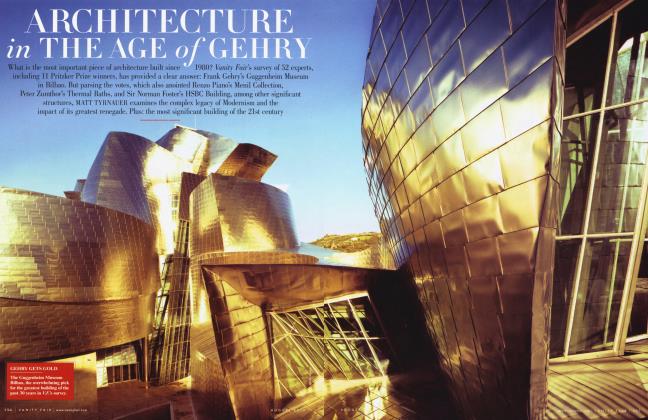

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe David Lynch of Architecture

How did a weird self-proclaimed iconoclast like Peter Eisenman become the architect of the moment? He's a Philip Johnson protégée and Jungian sports freak who talks shop with Jacques Derrida and crafts his buildings with visions of terror and repression— and international clients are clamoring. JOHN SEABROOK meets the man who wanted to build a Disney hotel underground

"Wexner hates that building," says Philip Johnson. "It drives him mad."

It is not uncommon to hear Peter Eisenman described as the next Philip Johnson, the heir to the throne of American architecture. Eisenman did not begin practicing full-time until he was fortyeight, which was ten years ago. Before that he was lecturing, writing, and theorizing about architecture, organizing movements, editing a journal, steeping himself in contemporary philosophy, and comporting himself in a manner that got him the nickname "Peter the Mad."

Before 1980 he produced only four small, white, abstract houses, and while these were successful within the intellectual wing of the profession, they enraged several of the people who had paid for them. One couple refused to live in any part of their house but the basement, and another client used to turn up at his lectures to heckle him. A third client became convinced that her husband was more interested in their house than in her and began taking out her anxieties on Eisenman. "The head was really out of control" is how Eisenman characterizes this period in his life. "The head was giving lectures and running around to conferences and juries and nothing was getting built." Finally the head was examined by a Jungian psychologist. As a result "1 was able to get out of my head and put myself in the ground." He formed a partnership with an architect named Jaquelin Robertson and began pursuing commissions.

Almost everyone within the profession doubted that Eisenman, who has described what he does as "exploring the possibility of a truly horrific environment," would have much success in persuading developers and university presidents and city planning boards to spend $20 or $40 million building truly horrific environments of their own. They were wrong. Leslie H. Wexner, the chairman of the Limited, spent $25 million to build the Wexner Center for the Visual Arts in his hometown of Columbus, Ohio. It opened last fall to nearly universal acclaim, with the possible exception of Leslie Wexner himself. "I hear he's appalled by it," Eisenman says, not unpleased with the idea. "Wexner hates that building," Philip Johnson says. "It drives him mad. And the more publicity it gets, the more he hates it, because it reminds him that somehow he hired this madman to build it for him."

At any rate, the publicity from the Wexner has brought Eisenman more projects—a convention center in Columbus, a school of design at the University of Cincinnati, a computerresearch center in Pittsburgh, two hotels in Spain, a housing project in the Hague, and an office building in Tokyo. He is now, as Michael Graves said recently, "the man to beat in the competitions." He has been equally successful in the universities. "Everywhere you go in the schools," says Paul Goldberger, the New York Times critic and cultural editor, "you see the students doing Eisenman." Not everyone is sure what "doing Eisenman" means, or that students ought to be doing it. Whatever it is, Philip Johnson made it the thing to do two years ago, when he curated a show called "Deconstructivist Architecture" at the Museum of Modem Art.

The Wexner Center project began in 1982, with the announcement by Ohio State University that it was holding a competition for a new arts center. The competition pitted Eisenman and a local architect named Richard Trott against four illustrious and much more experienced architects—Cesar Pelli, Arthur Erickson, Gerhard Kallmann, and Michael Graves, "the big boys," as Eisenman calls them. Each submitted a proposal that in one form or another reflected the dominant style of the age, postmodernism. Eisenman did something different. He built no obvious front entrance. He buried most of the functional components of the building in the ground. In front of it he partially reconstructed an old armory that had burned down some years before. Through the heart of the site he erected a 516-footlong rectangular white steel grid that had no practical function whatsoever, though it did happen to mirror the grid Lewis and Clark had made of the Northwest Territory, the grid of Ohio, and the city grid of Columbus. He worked these grids through the whole building, with different-size columns, different-colored floor stones, and different tints of glass. Finally he oriented the whole site so that it was aligned with the football stadium. The jury chose him unanimously.

In retrospect (Continued on page 125) (Continued from page 78) Eisenman's victory has been seen as a landmark in architectural history, a referendum on the essential question of the day: Is a building an artifact composed of symbols and historical allusions, as the postmodernists would have it, or is it an abstraction of space and light? The Wexner, it is said, marks a return to the abstraction of modernism, except that instead of an abstraction based on logic, it is based on illogic. It is hard to say precisely what this style of architecture is; it is easier to say what it isn't. Mark Wigley, the associate curator of the Deconstructivist show, defined it as "a devious architecture, a slippery architecture that slides uncontrollably from the familiar into the unfamiliar, toward an uncanny realization of its own alien nature: an architecture, finally, in which form distorts itself in order to reveal itself anew." Other critics think that Deconstructivism isn't a movement at all; rather, that it represents the apotheosis of Peter Eisenman's personality. "The sound of one mind laughing" is how Charles Jencks, an American art critic who lives in London, describes Deconstructivism. Eisenman himself, having inspired the movement, now characteristically likes to deny he is a part of it: "If there is a Deconstructivist style, I would certainly be the first one to turn against it."

"I appeal to that little bit of morbid anxiety in the American heart."

Peter Eisenman isn't around very much—he may be in Portland, Oregon, giving a lecture, or in Chicago, teaching a class, or in Barcelona or the Hague with new clients. When he is in town, however, he is typically to be found in his office on West Twenty-fifth Street, with his feet on his desk, his arms folded, talking. He conducts conversations with the mannerisms of a referee: whistling to indicate some logical foul, flashing a T sign—time out—and explaining where you went wrong. Or he makes a series of rapid jabs at one's head and says, "Exactly!" One can never be sure which it will be—whistle or pointy-point-point. When he starts saying "I hear ya, I hear ya," he has stopped listening.

Eisenman has a large head, and it seems to grow larger the longer one spends in its company. It is handsome and youthful-looking, well covered with thick whitish hair. His signature outfit, which almost never varies, is a striped shirt, pale-yellow bow tie, red suspenders, and rumpled gray suit pants. When the gray suit is too rumpled, he shows up in a white one. He wears silver wire-rimmed glasses, and usually has a gum massager—sort of a huge toothpick—stuck in the comer of his mouth.

Eisenman's buildings are beautiful, and one sure way to agitate him is to tell him that. He isn't interested in beauty. He is, as his former partner Jaque Robertson puts it, "a first-rate artist who would rather be seen as an intellectual." He is interested in developing an architecture that is more consistent with modem philosophy, specifically the philosophy of Jacques Derrida, who is his current mentor. He would like to displace the meaning of buildings, and produce in its place a kind of ontological void which the viewer of the building must fill. His argument, insofar as one can be clear about it, is that the hierarchical space of classical form embodies a metaphysic that no longer applies to the world. We live with many meanings, or with confusion, so architecture has to reflect that. Literature reflects it, painting reflects it, music reflects it, but architecture still reflects the classical notion of presence. Eisenman wants a building to reflect absence.

In 1986 he and Derrida were commissioned by the French government to build a garden in Parc de La Villette, in Paris. The two of them held a series of lengthy Socratic conversations about how they ought to proceed, the transcripts of which fill a filing cabinet near Eisenman's desk.

J.D.: .. .You could strategically insist on absence....

P.E.: .. .But let's say presence of absence. We use two terms in the work we've been doing: absence of presence, which is nothing, and presence of absence, which is vacant to me.

J.D.: Then thematizing is to make the absence of presence.

P.E.: What we're talking about basically is the condition which we would call presence of absence. So it's another presence.. .it's, basically, a presence of absence.

Much time is spent trying to define what presence of absence means:

P.E.: In the work we have been doing we distinguish between the presence of absence, and the absence of presence. It is through this distinction that we attempt to activate absence and operate simultaneously with presence and absence in order to critique the anthropocentric tradition in architecture which represses absence.

Bickering ensues.

P.E.: No, no, it's not a void, it's material. J.D.: It's not substantial matter, but not void.

P.E.: Not void, O.K.... It's not silent, it's mute. It isn't able to project on any—

J.D.: It's non-readable.

P.E.: Non-readable.

J.D.: Non-readable.

R.R. [another architect]: I have a question in italiano.

P.E.: Va bene. E meglio per te.

So far the garden has not been constructed, although Rizzoli plans to publish the highlights of their conversation in a book—Choral Works.

It might be supposed that Eisenman is concerned more with metaphysics than with everyday issues, and that his appeal as an architect is confined to a small group of intellectuals. This isn't how Eisenman sees himself, however. On the contrary, he believes that his preoccupations— alienation, anxiety, chaos—are familiar to a large part of the American public. He likes to refer to himself as "the David Lynch of architecture." By this he means, "I think I appeal to that little bit of morbid anxiety that has always existed in the American heart." His mission, as he sees it, is to do with buildings what David Lynch does in movies—"to discover the unhappy ending in architecture." In short, to give people buildings that look the way (he thinks) they feel.

In 1988, for example, Michael Eisner asked Eisenman to design a $30 million hotel for Euro Disneyland in France. For Eisenman, this was a plum. To be commissioned by the kingdom of Disney may be the highest honor a contemporary architect can attain, and Eisenman therefore pursued his investigations with unusual vigor. "I started to think about the dark side of Disney. You look at the major characters, Mickey Mouse, Dumbo, and you realize something very frightening is going on there. Or Pinocchio and the Whale. Terrifying. It's got a saccharine coating, but there's arsenic under it." He presented Eisner with a model of a twohundred-room hotel that was entirely underground, with light shafts going down to each room. Above the ground was a stage set of cheerful middle-class homes, and a steel lattice, sort of a monstrous jungle gym, which is the Eisenman signature. Michael Eisner declined to build it.

Eisenman is unsure if Eisner thinks he is crazy, or if he wants Eisner to think so. "Why wouldn't he hire me? It isn't as if he isn't hiring all my buddies. I think it's because I'm a little too scary. I'm not interested in beauty. I'm interested in terror. With Michael Graves you get blue-chip; with Peter Eisenman you get red-chip."

A young man with slicked-back hair appears in the door. "Hey, Pete, want to come take a look at the armadillo?"

"Sure, man," Eisenman says, and follows him out to the studio.

The staff—about thirty altogether, mostly young men—is working at tracing tables in one large, battered room. Roughly a third are wearing the Eisenman softball uniform, mock turtlenecks with the French word AMNESIE written on them— Eisenman spelled backward, almost.

"Who're we playing tomorrow night?" Eisenman asks.

"Cobb," an assistant says.

"Cobb!" Cobb is the firm of Henry Cobb, James Ingo Freed, and I. M. Pei, which, Eisenman says proudly, his firm defeated in last year's championship game, in Central Park. He adds that he also totally humiliated Graves's firm, 163. "I wanted to show you could do good design and play good ball. We used to be terrible. We were great architects, but we were a bunch of wimps."

"How did you get better?"

"We recruited. See that kid over there?" He points to a stocky fellow who is stowing drawings in a plan drawer. "Played third base for Ohio State. The Yankees gave him a tryout and dropped him, and we picked him up."

"For his architecture?"

"No, for his ball. But he's a good kid. We've got him on a reading program— Barth, Poe, Hawkes. That kid over there? He was the windsurfing champion of Italy. That kid there was the scrum half on the Portuguese national team."

Eisenman turns his attention to the armadillo, which is the latest and most daring project in the studio. It is a design for a small office building for a Japanese client. One of his assistants is constructing a cardboard model of the building that Eisenman himself will be carrying over to Tokyo this weekend: it looks like a heap of fractured plates, like ice that has been blown up from underneath. In researching the site, Eisenman found out that a small geological fault ran through the area. Another architect might have downplayed this, but Eisenman seized upon structural weakness, and plate tectonics, as the central metaphor in his design. "We wanted to do a building that showed the land triumphing over man," he says. "So we took a typical office slab and we hit it with a surface wave, and we got some ground eruptions and this residual scum of a building left over, plus some voids where the building used to be." He picks up the model and turns it in his hands. "It's very primal. It's like the shell of some strange animal, like the back of Godzilla emerging from the ground. It comes right out of Japan."

He isn't especially concerned with what the Japanese will say about Godzilla, armadillos, and plate tectonics. "Hey, man." He holds up his hands in a "Don't blame me" gesture. "They asked for something aggressive. They wanted wild. I'm givin' 'em wild."

The most concise answer to the question "How is it that someone as peculiar as Peter Eisenman has gone so far in architecture?" is "Philip." Philip, as everyone calls Philip Johnson, is the most powerful architect in the world, and Philip is Eisenman's champion. It was Johnson who said, when the Wexner Center opened, that it was "a great building," one that "portends. . .a fundamental change for architecture." It was Johnson who curated the "Deconstructivist Architecture" show, the show that gave the stamp of the academy to Eisenman's work. It may have been Eisenman who persuaded Johnson to do it, but it was Johnson's name on the program, and so the show had Johnson's immense authority behind it.

It is not by Johnson's stewardship alone that Eisenman has thrived; it is also by Johnson's example. For nearly six decades Johnson has been the great impresario of American architecture. He has built some spectacular buildings—Pennzoil Place in Houston, MOMA'S East Wing and Sculpture Garden, his own glass house in Connecticut—but he has never been, as he has said, "a form giver." His immense influence derives mainly from his ability to promote the form givers' work. He has done this through exhibitions, the most famous being the International Style show of 1932, which introduced Le Corbusier, Gropius, and Mies van der Rohe—the fathers of modernism—to America. He has used his social and political connections to get his proteges commissions. He has promoted other architects with his own work, by interpreting their styles. "The curious thing about Philip and Philip's role is that he is the most powerful figure in architecture without being anywhere near the most influential architect," Paul Goldberger said recently. "He does this by dispensing commissions and handing out honoraria, getting grants, organizing symposia, organizing shows, and that sort of thing. And Peter is following Philip in that."

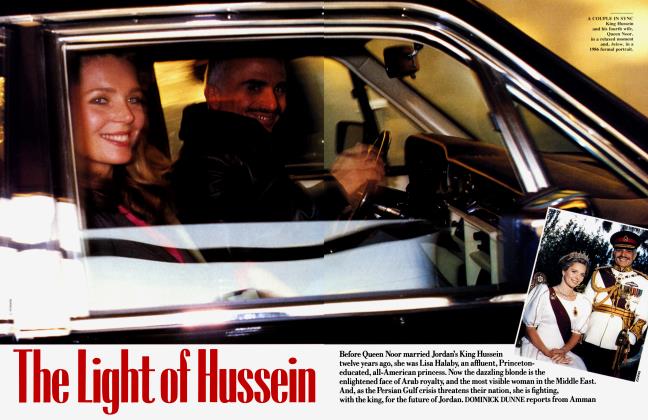

Johnson's office is on the third floor of a Johnson building, "the lipstick building," so called for its elliptical shape and for the flame-finished red granite that covers it, located at Fifty-third and Third in Manhattan. There are Barcelona chairs in the waiting room and some Warhol flower prints. There is a semicircle of immense plates of shattered glass that arc around half the room, like enormous windshields after an accident; they form the partners' offices, and behind them one can see the partners themselves, broken into Cubist fragments by the glass. One day last summer there was Johnson himself, eightyfour years old, slim and impeccably dressed, with a white crew cut and his Le Corbusier-style glasses, peering intently at a cardboard model of a skyscraper that may one day exist in Times Square.

"I think Peter's the most significant architect alive," said Johnson, pushing his skyscraper aside. "The work is important, of course. The Wexner Center is terribly good. But the personality is really the most important thing about Peter. He has a tremendous appeal to architects as men—he has single-handedly fostered this whole male-bonding thing between today's architects. He is always getting us together and saying, We must discuss this, and this. He is always at the center of what's going on. He loves to analyze this quality in himself. Or, rather, he loves to tell you what his analyst says about him. 'Peter, you've got to be at the center of attention. Why is this, Peter? Even when you're not at the center, you are.' Of course, I'm happy to say that's nonsense. But Peter thinks it's true. And it is true, in a way. He has a kind of dynamic power over all of us.

"Of course," Johnson went on, "Peter knows nothing about architecture. What does he know about light? Corbusier used to say he built with light. He knows nothing about materials, like Mies. Materials? Peter would build with chewing gum. And yet the Wexner Center has the most wonderful light you've ever seen, and the most brilliant use of materials. It's a wonderful building. And yet Peter knows nothing about building. The door handles at the Wexner Center are sheer nonsense. They went into the back room and welded two pieces of metal into an L and slapped them on the door. And yet they are the most marvelous door handles you've ever used. The very best. You see, that's how he is. The Wexner has all the faults of Peter, his childishness, his naivete. It doesn't even have an entrance, for God's sake. But somehow out of his naivete comes his genius. He's like a boy playing with mud pies.

"Has he started in on his Jewishness with you? Oh boy. Well, and of course I'm supposed to be the arch-anti-Semite, so he's always talking about it with me. There's no end to it. Of course, now it's his sex life. Well, it's wonderful when a man of fifty-eight discovers his sex life, but it's not my sex life, is it? Honestly. He can be the most excruciating person to listen to. He'll mount one of these intellectual hobbyhorses and ride off into the mist. Grids of Ohio, Jeffersonian grids, grids of the football stadium. It's absolute nonsense. Now it's this plate-tectonics business. Plate tectonics, my eye. I wouldn't have thought the Japanese wanted to be reminded of earthquakes, especially if you're building for them. But, of course, that's Peter. He's always hiding behind this web—web is a good word, isn't it? Marvelous word, web. He doesn't really understand Nietzsche. He doesn't understand most of the stuff he spouts. He really is the most tremendous bullshitter. But, and here's the point, he's better than a theorist. He's an artist. But he requires theory to make his art, just like Mies required technology, and Hannes Meyer required the proletariat. It's terribly hard to do design. We all need our crutches. And Peter's is his mind."

In one house he attacked the notion of the bedroom by placing a column in the middle of it.

Eisenman was bom in East Orange, New Jersey, in 1932, into a family he describes as "basically out of a Philip Roth novel." He was the elder of two sons. His parents were well-off: his father was a chemist in the fur industry; his mother played a great deal of bridge. As a child, "I was afraid to be intelligent. I didn't want to stand out as a bright Jew. It was very interesting. I was always sublimating my Jewishness. I've never gone out with a Jewish woman. Typical syndrome. I think it goes back to the feeling that intermarriage will save you from Hitler.

"My father couldn't understand why I never exhibited aggressive behavior. 'Why don't you get in some fights?' he'd say. My mother was always telling me that I was out of it. It was true. I lived in a totally mythological world. I would invent whole baseball teams in my head, and hold games, and then I would call friends at night and read them the statistics, and then publish them in my own newspaper, Eisenman Eastern News Service. My father would say, 'What is he doing up there? Get him out. Get him into a fight.' "

He wanted to go to Harvard. "My father said, 'What Harvard? Rutgers is good enough for you.' " He ended up going to Cornell, where he became a cheerleader. "I was the ultimate college man. You know, the white sweater, doing cartwheels on the sidelines whenever we scored a touchdown—I was really into it. I really blasted out socially. But I was on the point of flunking out. So I went to see my dorm counselor and saw he had all these models of buildings lying around his room. I said, 'What's this?' He said, 'I'm an architect.' I said, 'You mean you can do this stuff in college and get credit for it? Great! This is what I should do.'

"Now, up to this point I had never made a decision in my life. So I went home, gathered my parents together, and said, 'I want to be an architect.' My father looked at me and said, 'This is one of your tricks.' And my mother said, 'Being an architect isn't something a good boy should do.' "

His senior project was a design for a frat house on the Cornell campus. After graduation he served in the army, and was sent to Korea as part of the peacekeeping force after the war. He built an officers' club, and the roof caved in during the dedication ceremonies. In 1960 he went to Cambridge University as an assistant lecturer, and he spent three years getting his Ph.D.

"At Cambridge I got totally into ideas. Colin Rowe [the architecture critic] was there. He told me, 'You're a great architect, but you're stupid.' He became one of my mentors. Also, I had this romance which was a tragic situation, which I would prefer not to talk about, but which we can talk about if you want to, and out of that I met my wife—I was teaching with her uncle, who was Christopher Comford, Charles Darwin's great-grandson. My children are direct descendants of Charles Darwin."

In 1963 he returned with his wife to this country and got a job teaching at Princeton. He also began to build houses that were "against the traditional notion of how you occupy a house," in accordance with his belief that "I think it is exactly in the home where the unhomely is, where the terror is alive—in the repression of the unconscious." In one house he attacked the notion of the bedroom by placing a column in the middle of it, so that it was impossible to install a bed. In another house he built a phantom staircase along the wall of one room, and in the middle of a bedroom floor he left an eight-inch-wide rectangular slot that opened onto the floor below. There was a rumor that after falling into it the owner, Richard Frank, had to be removed by the fire department, but Frank says this isn't true. ''I just slipped in it for a second, that's all."

Eisenman's practice did not flourish. His reputation as a theorist, however, grew. "I never think about Peter when I'm designing a building," Michael Graves says, ''but I do think about Peter when I'm talking about a building." Eisenman lectured his peers about what they ought to be doing. Those he could not persuade he intimidated. ''He's almost rabbinical," says the California architect Frank Gehry. ''It's always, You must do this, you must say this. He's always organizing something—we all look to him for that. O.K., Peter, what's next, Peter, what's it going to be, Peter? He's like a great chess player. He's always got some new move lurking, and you've got to figure out what it's going to be. He loves to get people involved in his schemes, like Deconstructivism. I don't even know what he's talking about when he talks about Deconstructivism. But Peter said I should be on his team, so I said O.K."

In 1967, Eisenman conceived the idea of starting his own architecture school, and he persuaded several trustees at MOMA to pay for it. He rented the attic of a warehouse on East Forty-seventh Street, and offered lectures four nights a week. The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, as it was called—''Most of us just called it the Eisenman Institute," says Philip Johnson—became the most famous architecture center of the seventies, a sort of Cinema Twelveplex of ideas. There you could hear Leon Krier, Prince Charles's pet architect, lecturing about Nazi sculpture while the audience screamed at him. There a few people saw Gordon Matta-Clark blasting out the windows of an exhibition space with a gun as a statement on the architectural profession's lack of concern for urban decay. Eisenman sometimes participated in these spectacles, but his special genius was to remain behind the scenes, producing and publicizing, inspiring collaborations, drawing up manifestos, recruiting allies, pitting antagonists against one another.

The institute lasted until 1983, and it indelibly marked contemporary architecture. A whole new discipline—how to talk about buildings—was created in the universities, taught by people who call themselves "object theoreticians." A new language, Eisenmanese, began to be spoken by architects: "The Amnesiac (pre)Text for an American Absence (exile) (under)vvn'tes ([under]r/g/ite) repeated attempts at healing an irreparable wound" is the first sentence of one of Stanley Tigerman's essays. Ideological one-on-one contests between architects became a favorite feature of the architectural journals. Once in a while Eisenman would get all of the teams together for a tournament. The ideas were lofty at these events, the civility generally low. "We dare to meet here, to talk about this miserable hole in which I am sure none of us would want to spend more than five hours—it is a prison" was the opinion of Leon Krier regarding a windowless house by Tadao Ando of Japan, presented at one of Eisenman's conferences, in Charlottesville, Virginia. Krier then proceeded to tell Eisenman and company what he thought of them. "The level of discourse is such a miserable intellectual ruin that I feel like leaving. On the other hand, there are about twenty people here who are responsible for the architectural scene nowadays—that is, not only for how houses and buildings look, but how cities are going to be built and shaped. So, for God's sake, I plead with you to talk about the real problems—we have not come here to listen to ways of relating inside to outside space. We all know how to do that. We are all architects. We also know that our cities are in ruins, that the legislation now in use is destructive. Why can't we talk about that? Why don't we talk about these problems? I am not making them up. As architects, you are making the problems, and now you are being punished—not by God, but by a society that despises you."

In the late seventies Eisenman went through a sort of mid-life crisis. He went into analysis and separated from his wife. He started a relationship with one of his students. "I realized I had to come down out of the clouds. I was no longer interested in being a cult figure. I began to see the institute as this giant sublimation of my personality. All these other architects I was promoting were really just surrogates for me. Even Philip was a surrogate for me. See, I think you have to look at my psychological makeup. I have a strong ego and a weak ego. It's this conflict between the redneck and the idealist." He explored his conflicts with two Jungian analysts. "My analysis put me into sensation. That's what my Cincinnati building is all about. It's my sensual side. You see, I've always felt displaced. My Jewishness comes in there, you could argue. But I realized it's too easy to be displaced when you're alienated already." The outcome was that he decided to build. He found a partner—a temperate Virginian named Jaque Robertson, whose major patron, the Shah of Iran, had run into difficulty—who had managed to attract three limited partners.

One day last summer, while Eisenman was sitting in his office, a woman named Nanette called from Los Angeles. She said she wanted to live in an Eisenman house. She had seen an interview with him in the paper—one of the many stories that have appeared since the Wexner opened a year ago. Also, she had recently read one of his essays, "Transformations, Decompositions and Critiques: House X," and had been moved by the argument. Even Eisenman thought this was a little suspicious. The essay in question begins, "Within the text there are two voices. One voice seems to be the narrative voice of the architect of House X, and the other the voice of the critic. But this second voice can also be read as that of the architect of the earlier houses while the first voice can be read as that of the house itself." What follows is a nutty conversation between two characters in Eisenman's head on the subject of "the apparent inability of modem man to sustain any longer a belief in his own rationality and perfectability."

"I think she must be crazy" was Eisenman's opinion of Nanette. He also suspected she might be interested more in the architect than in the architecture—"You get that all the time." Nevertheless, he was, despite his critical success, a little short of funds.

Nanette was a single woman in her early forties, with bleached hair, a deep tan, and a tank-top shirt. She picked Eisenman up at the L.A. airport, and drove him over to the site. On the way, Eisenman attempted to browbeat her.

P.: So I'm trying to figure out, what do you do during the day? I mean, after you work out.

N.: I'm usually catching up on errands. I have more than the usual level of nonsense in my life.

P.: Are you done by four?

N.: Well, I don't like to do anything that involves thinking after six.

P.: What do you do for dinner?

N.: Oh, I have dinner. The Neiman Marcus of supermarkets just opened near my house.

P.: Do you entertain?

N.: No.

P.: Do you play sports?

N.: No.

P.: So why do you need these extra bedrooms?

N.: Well, sometimes the lamas come over. I'm taking Buddhist teaching, mostly perception.

P.: So it's for the lamas.

N.: Right.

P.: So you want a backdrop for your metaphysical existence. Let me ask you something else. Why do you want me?

N.: Because I read "House X" and found it quite wonderful. I lived with a man for a period of time who was into rational-type thinking. In fact, that was the reason I married him.

P.: What happened to him?

N.: Oh, we got divorced.

P.: [pouncing] So maybe you're not comfortable with rational-type thinking.

N.: [unfazed] Well, it hasn't always been my goal to live with a man.

P.: [defensively] I'm not suggesting that. I'm just trying to think about your thinking.

They arrived at the site, which was a thirty-by-ninety-foot lot in Venice. Nanette showed him around, talking cheerfully about her daily routine, and resisting, or not noticing, all of Eisenman's efforts to bring up the dark side of things. She said that the trees and the birds were more a part of her life than people, and that she imagined living in a house that was like a tree, full of light.

P.: Let me ask you something. What about living underground?

N.: Underground. Hmmmm...I could have artificial lights.

P.: Well, I don't mean entirely underground, but I'm very interested in digging right now.

N.: It's a thought.

P.: See, what Peter Eisenman does is, he upsets things.

N.: [serenely] I want to be upset.

P.: [upset] Peter Eisenman isn't necessarily interested in doing what you want to do. He's also interested in doing what he wants to do.

N.: You mean no closets and no bathrooms?

P.: No, I mean you would have to adjust.

N.: I can adjust. Look, I don't really own this property. The birds, the squirrels, a lot of things own this.

P.: Do you know how many people are going to come see your house?

N.: Do you know how many people use your toilet?

P.: I'm just saying, people come to look at my houses. Photographers, students, journalists. You're not going to have privacy.

I have a strong ego and a weak ego. It's this conflict between the redneck and the idealist."

N.: Well, I don't look at it from that point of view.

Eisenman could think of nothing to say. Here, for once, he had met his match.

Philip Johnson arrived at the Four Seasons Grill Room, which he designed, at his usual time, 12:30, and proceeded to his usual table, which is the best one in the restaurant. His guest, Peter Eisenman, had not yet arrived, and so Johnson had some time to receive the ministrations of the waiters, and the fixed attention of the neophytes in the room, and the good wishes of several of the regulars: Mort Janklow, the agent, who was sitting in front of him, and Leonard Lauder, of the cosmetics firm, who was on his right. Clustered around were some of the other regulars—publishing lords and midtown financiers—who make the Grill Room perhaps the most rarefied salon of capitalism in New York City.

Presently, Eisenman sauntered across the room. He had pressed his gray suit for the occasion, and he had been uncharacteristically careful about tying his bow tie.

"Hello, Philip," he said gravely, lowering his voice several octaves for effect, and scanning the room. One day, perhaps, this crowd would pay him the kind of obeisance they pay Johnson; for now, however, nobody much noticed him. He scowled and darted his eyes around at the well-known faces. Johnson seemed amused by this little performance. He said that he'd enjoyed their dinner the night before, and that he'd liked Cynthia, Peter's new girlfriend (who quickly became his fiancee). Eisenman looked pleased. "Oh, really? Yeah, she's O.K.," he said proudly.

Eisenman scowled again. He withdrew from his pocket a picture of a newly completed building in Tokyo that would be opening the following week. Johnson studied it in silence for a while. "That really is the most marvelous thing," he said at last. "How would a person design such a thing?"

"All we did was, we said to the Japanese architects, You design a typical office building and then we'll come in and insert a piece that will destroy the purity of your work. And this Japanese found this very intriguing, so that's what we did."

"Marvelous," said Philip, focusing on the photograph.

"See, it's like a kind of disease that has grown on the side of the building."

"Yes, I see. May I keep this? I want to show it to some people." He put the photograph in his pocket.

"By the way, we're redesigning our newest building," said Peter.

"The armadillo?" Philip asked.

"Yeah, the armadillo. Plate tectonics," said Peter.

"Plate tectonics makes me throw up," said Philip. "I don't mind the armadillo."

"The armadillo," said Peter quickly. "The Japs want us to change it."

Philip nodded and lightly broke a crust of bread. "Because they don't like it or can't build it?"

"Can't build it," Peter said.

"Well, they'd certainly have an interesting time trying to build it."

"Exactly," Peter said, and made the pointy-point-point at Philip's head.

"And yet," said Philip, "maybe the building does need some dullness. Because dullness is extremely important to what you do."

"Exactly." Pointy-point-point.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now