Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLEAVE IT TO CHEEVER

Will the publication of the late author's journals be the last of the Cheeverfamily outings?

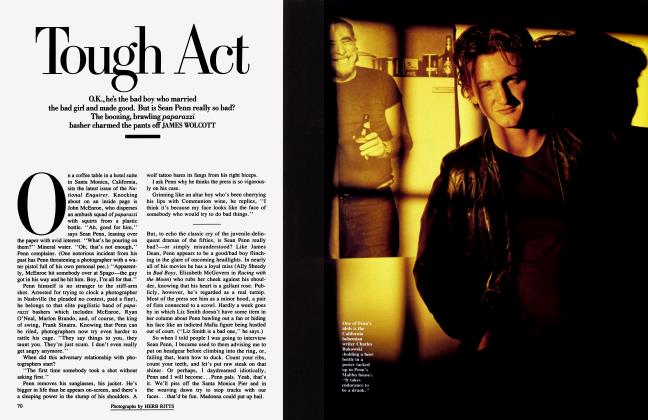

JAMES WOLCOTT

Mixed Media

Saints should be judged guilty until proven innocent, argued George Orwell. Does this apply to sinner-saints as well? Since his death in 1982, John Cheever has acquired a celestial harp with a few strings missing. A writer of novels and short stories, Cheever created lost paradises out of suburban lawns. A

river of gin ran through his district. It was always cocktail hour in Cheever

country, a time of dusk, sliding dentures, and oncoming chill. Critics accused him of painting fine cracks on the skulls

of Easter eggs. Irving Howe, for one, wanted him to lob hand grenades into the living room. But Cheever's luster had a

hard coat, outlasting flur^ ries in literary fashion, f Unlike the careers of so ~ many American writers, his enjoyed a winter bloom. His novel Fal-

coner captured the cover of Newsweek, his collected Stories of John Cheever won the Pulitzer Prize. As

his craggy shadow grew, however, his secret life began to leak. The lord of the manor, we learned, had a burning yearning for other men.

His daughter, Susan, "outed" him in her memoir Home Before Dark. His son Benjamin gave us a bigger tour of the closet in his edition of his father's let-

ters. And Cheever's biographer, Scott Donaldson, documented how his twofisted boozing led him into the lap of A. A. Such bombshells boosted his mystique. Put to rest was the notion of Cheever as a slick practitioner of middlebrow affirmations. Eclipsed in five o'clock shadow, riddled with ambiguities, a double agent working both sides of the seedy bed, he was now a Tortured Artist for our time. In the age of recovery, his sobriety was a state of grace. The canonization of this sinner-saint reaches its final stage with The Journals of John Cheever (Knopf), edited by Robert Gottlieb. To sensitive readers these pages will read like redemption. I wish I could be that sensitive. I find much of the book to be holy baloney.

For all its alcoholic content, Cheever's prose was famous for its pristine coat of paint. He prided himself on its milky skin. In his letters he writes of Bullet Park, "The book is very, very clean.... While all my friends are playing stinkfinger and grabarse I admire the beauty of the evening star." He suffers the stigma of being quaint. "I seem, with my autumn roses and my winter twilights, not to be in the big league." Still, one must persevere. "Oh, to put it down, and to put it down with the known colors of life: the reds of courage, the yellows of love." But the strongest dye pouring through the stainedglass windows of Cheever's journals is purple. Lord, how he piles on the pomp. He can't do a simple Edward Hopper scene of male loneliness without adding eight layers of eyewash. ' 'A lonely man is a lonesome thing, a stone, a bone, a stick, a receptacle for Gilbey's gin, a stooped figure sitting at the edge of a hotel bed, heaving copious sighs like the autumn wind." A visit to Shea Stadium inspires a vast mural. "This is ceremony. The umpires in clericals, sifting out the souls of the players; the faint thunder as ten thousand people, at the bottom of the eighth, head for the exits. The sense of moral judgments embodied in a migratory vastness." I guess the Mets lost.

Nothing empurples his prose more than strolling the grounds of God's estate. Such qualities. He can sound quite the squire describing his relations with his wife, Mary. One fine spring morning, "I mount my wife, eat my eggs, walk my dogs." At least he didn't walk his wife and mount the dogs. (These days, you never know.) But more often in the journals, he finds himself sharing the doghouse. "So I retire to the spare room—the thousands of nights I have spent on sofas!" Rebuffed, he resorts to adultery, and meets other rebuffs. "We lunch and return to the room, but the kissing is halfhearted, and when I suggest a fuck she says gently that she somehow doesn't feel like it. The fish she ate for lunch..." He is soon embosomed again with Mary, courtesy of a thunderstorm. "The dogs are frightened, the lights go out. I mount my beloved, and off we go for the best ride in a long time."

The mess of Cheever's life is a mud slide. Viet it's provided such posthumous fame that his fiction has finally been elevated to the big league.

Cheever's admirers depict him as the last vestige of chivalry. But what kind of man talks about "mounting" his wife? His gallant diction—"So I am gentled and gentled and gentled"—gussies up a fundamental condescension. Susan Cheever points out that women in her father's fiction are punished once they step outside their aprons. In his letters Cheever makes women sound like loose rinds. "I might point out, as an older man, that cunts that old lose some of their grip," he cautions a male buddy. "However," he adds with a twinkle in his foxy eye, "you have a much bigger and younger cock than I."

For all his lofty disdain about his contemporaries' playing stinkfinger and grabarse, no one was more bushytailed than he. Beneath his Christian homilies races a pagan desire to horn nymphs and satyrs alike. "Run, run, run ballocksy through the woods..." he chants. He does dive into a pond and pick a lily. But the gray-flannel fifties of Eisenhower's America are no time for furry frolics. Married with children, middle-aged, Cheever finds himself drifting into bathhouses, balconies, limbo. He understands that a cheap shot in the shower could chop his life in two. (Good-bye, country club. . .hello, YMCA.) It may imperil his very soul. He's a sodden raincoat venturing into the void.

But then—such sprawl. When Cheever describes sex with men, he ditches the genteel parlance of being gentled and does the Funky Chicken. After drinking another man's spit (his sparkling phrase), "I took a shit with the door open, snored, and farted with ease and humor, as did he. I was delighted to be free of the censure and responsibility I have known with some women. I could spar with him if I felt like it, feed my cock into his mouth, and complain about how smelly his socks were. And I was determined not to have this love crushed by the stupid prejudices of a procreative society." Noble sentiments, but how about shutting the bathroom door first?

Cheever wanted sex between men to be.. .well, manly. He despised any titter of effeminacy. The pursed lips of old queens appalled him as much as the loose grips of older women. (An outburst in his letters about an elderly gay couple is even cruder than usual for him.) Cheever wanted to have it both ways, getting his rocks and socks off at the No-Tell Motel while playing the solid papa back at the Ponderosa. He's no airy fairy, unlike some he could name. His life has foundation. His closet was built with walls of bad faith. Cheever once boasted to his son that his epitaph should read, "Here lies John Cheever / He never disappointed a hostess / Or took it up the ass." His attitude seems to be that, because he spumed the submissive role, he was superior to mere homosexuals. Don't lump me in with those old losers, he seems to be saying. I went down on my knees for no man. Chalk another one up to denial.

The source of his denial was his drinking. Watching Cheever marinate his liver in the journals made me sympathize with Cyril Connolly's outburst "I never want to read about another alcoholic. ... [Alcoholism] is neither poetic nor amusing. I am not referring to people getting drunk, but to the gradual bloating of the sensibilities and the destruction of personal relationships involved in such long-drawn-out social suicide." Alcoholism drove a plow through Cheever's family, burying his mother, father, and brother. To Cheever's credit, he stopped short of social suicide himself, entering a program in the late seventies. Strikingly, he spares us the salvational tone many A.A. members use. He stays within the circle. And he's stoic in the face of cancer and cobalt treatments. By the end of the book Cheever isn't converting every situation into a spotlight on his fancy decay. He shows his Yankee flint. One closes the book with respect, and relief.

The relief comes from the firm hope that Susan and Benjamin Cheever have nothing left to drag out of their father's closet. It's become a cottage industry, carting out his debris. Susan Cheever recently published another memoir, Treetops. Benjamin Cheever pops up between the letters like a pup, offering inane anecdotes and generally making himself annoying. All of this backfill feeds the phenomenon Gore Vidal deplored in The Times Literary Supplement—the gossipy trend to read about writers rather than bother with their books. "Where the latest serious novel may sell a few thousand copies, a life of any truly messy author will sell the way novels once did."

The mess of Cheever's life is a mud slide. Yet it's provided such posthumous fame that his fiction has finally been elevated to the big league. His patchy novels are now honored, if not read, as the backstage dramas of a fractured psyche. He's been compared to such dark eminences as Hawthorne and Kafka. Does he belong in this league? No question his early stories have a swan-necked shimmer, like the ice sculptures in F. Scott Fitzgerald, and a spooky pathos. But in the later stories and novels, he works the church bells as if he's redoing The Song of Bernadette. Never far from rhetoric, he pimps for piety. One tires of Cheever extolling "the inalienable dignity of light and air." His epistles appeal to readers who want to be ennobled.

But this doesn't entirely explain why Cheever became a dead star. The cultural yearning for John Cheever isn't primarily literary, I think, but psychological-spiritual. It's a way of romancing and reclaiming the dead father in the Age of Recovery, of echoing his children's plea, "Why does the world get all of your goodness? Stop your drinking and cheating—share some of that grace at home." It's the same urge that makes us hold on to Hemingway long after his writing has gone to wreck. But Hemingway was at least a heavyweight bastard. He cleared a lot of land. Sainthood, even sinner-sainthood, is for smaller men.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now