Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

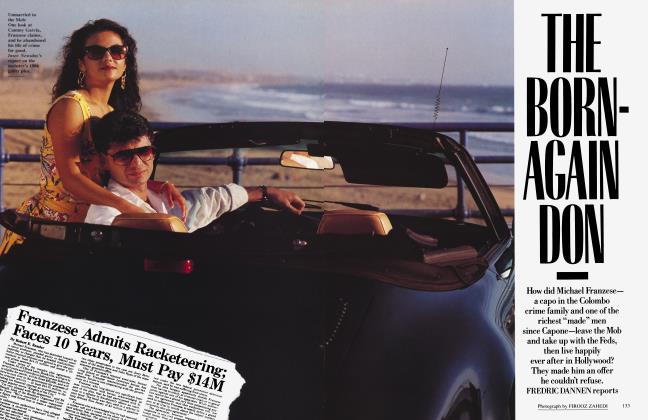

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSPRINGTIME FOR HOLZER?

Adela Holzer, Broadway's flamboyantly fraudulent producer, landed behind bars. But what's her next act?

LESLIE BENNETTS

Letter from Rihers Island

Controlled electronically by an invisible hand, the wall of bars slides open as if of its own accord, but as soon as one enters the enclosure, the metal grid closes abruptly with an ominous clank. The only furniture is a few molded-plastic chairs and child-size tables; each is made from one seamless piece of material, with no parts or hardware that could be removed and sharpened into a shank that could be used to stab someone. This is where Adela Holzer is permitted to see her visitor, except that right now she's two hours late for our appointment. Finally an exasperated guard tells me why: Holzer is balking in a holding pen on the other side of the wall, refusing to come out unless prison officials allow her to change into her own clothes instead of the regulation uniform. Contraband is more easily concealed in street clothes, whereas the shapeless jail-issue jumpsuit has no pockets or belt in which to tuck a vial of crack or a blade. The standoff seems hopeless; the officers are adamant, but Holzer will not budge. The situation is appealed to higher and higher authorities as the day wears on. Finally, miraculously, the bureaucracy capitulates, and a guard unlocks the door to the holding pen.

Tiny and triumphant, Adela Holzer sweeps majestically into the room, her head held high as if the years had suddenly melted away and she were back in her glory days, the glamorous Broadway producer once again borne along by the heady exhilaration of opening night. Impeccably groomed, she could be on her way to lunch at Le Cirque instead of behind bars at Rikers Island. Her small, astonishingly unlined face is carefully made up, and her dyed auburn hair is neatly set, although she tells me later that, in the endlessly inventive fashion of the veteran inmate, she had to roll it on toothpaste tubes. She is wearing a navy-and-white striped dress with a cinched waist and a broad white linen collar, as immaculate as if it had just been pressed by her lady's maid instead of extracted from a parcel-size locker in a jail cell. Adela Holzer has spent her entire life refusing to play by the rules that govern other people, not only insisting on spinning out her own dazzling version of reality but persuading others to submit to it as well, no matter what it costs them. Today, once again, she has performed her usual magic: reality is what Adela wants it to be.

This is quintessential Holzer, of course, but it's a tough act to maintain in jail. It has been two years since that dreadful day in February of 1989 when Holzer was accosted on the street by three investigators who had come to arrest her. She tried to bolt—"I thought they were mugging me!" she exclaims, full of righteous indignation—but they threw her over the hood of a car, slapped handcuffs on her, and hauled her off to jail. 'T couldn't believe it!" Holzer says, her eyes wide and guileless. Most of those who knew her could believe it all too well; it was, after all, the second time around.

This latest disgrace is a lot more difficult to explain away than the first catastrophe. That one she dispenses with easily. As she tells it, the reason she was apprehended in 1977 and booked on 137 counts of grand larceny and falsifying records (charges later increased to 248 counts of grand larceny and related offenses) was a sadistic prosecutor who waged an unaccountable vendetta against her. "I have been very victimized," she says sadly. It was all a terrible misunderstanding, compounded by the incompetence of her lawyer, Roy Cohn—"my biggest mistake." Yes, she served time—sentenced to two to six years for grand larceny, she served two—but she brushes off the unavoidable historical facts as if they were gnats buzzing too close to her face.

The really incredible thing was that, having been officially declared a criminal once, Adela Holzer—the self-proclaimed product of a wealthy Spanish family, the much-married Upper East Side hostess, the onetime toast of the New York theater, and the subject of adoring profiles detailing her extravagant life-style and trendsetting taste— should do it all again: start trying to produce a Broadway show, lure investors with yet another Ponzi-style investment scheme, and then get caught once more when her financial house of cards began to collapse. The show, which was called Senator Joe, never made it to opening night; Holzer ran out of both money and time. She still has difficulty acknowledging what happened. Charged with defrauding her inexplicably trusting investors of up to $4 million, she stood in a courtroom last spring and pleaded guilty to a single count of stealing more than $400,000 from one investor, in exchange for a reduced sentence. Notwithstanding her public admission of grand larceny, when she talks about it she always frames her words as if she didn't really do anything wrong, as if some awful concatenation of events had conspired to do her in once again. "I didn't do what they say I did, but even if I did. . ." is how many of her sentences begin. The mysterious alchemy by which inconvenient truths are transformed into a more palatable fantasy has proved useful behind bars.

At first, when Holzer was dumped in jail two years ago, her state of mind was dire, particularly after an unsympathetic judge set bail at a million dollars, an amount her family was unable to muster. "I was in shock," she says. "The shock lasted several months. Then I started to feel sorry for myself. I cried; I couldn't talk to anybody. I was in a state of oblivion. Nothing seemed to matter; all seemed to be precluded."

But despair is not a condition Adela Holzer has ever given in to for long. "Gradually I entered into another stage, of intellectual reasoning or analysis," she says. "Slowly a little light started to appear and grow brighter and brighter. What I can see is a big future for me. Somebody has to cash in on my imagination. Madonna could do Senator Joe in a movie. She would be fantastic!"

"If she told me the sun was shining, I'd go out to look-and I'd take an umbrella."

This is just one of scores of ideas. For two years Holzer's febrile imagination has been seething with schemes for yet another comeback. This month she becomes eligible for a work-release program. The question is what she will do with her freedom when she finally wins it. She has had a long time to make her plans.

Even in captivity, Holzer is endlessly inventive in devising ways to capture L the limelight. As the impasse in Iraq dragged on into December, she wrote Saddam Hussein offering herself in exchange for his American hostages, although she acknowledged that prison officials back home might not be persuaded by her self-sacrifice. Incarceration remains difficult, despite her not inconsiderable experience behind bars. Sometimes she is buoyant and optimistic. "I am a survivor," she declares confidently. "I'm already moving toward many different directions. I am going again to make it." Then there are the times she gets terribly depressed. "How long can you be strong?" she says to me one day, sounding desperate. "Every day is the same thing. It's so monotonous! The boredom is enormous. I have nobody to whom to talk; I am the whole day without speaking to people. It's so long—two, three years, it's an eternity, looking at the same walls, the same women, the same food! Finally you lose faith in yourself. You have to be very careful not to fall into a crazy state."

And sometimes she is just plain furious. "I'm going to get out from this prison with a tremendous hate," she tells me one day, her voice taut with rage. "This is stupid and cruel. I would do much better helping poor children in the street or taking care of sick people— or making some money to pay people back. Anything would make more sense than this. It's absurd to put women like me in jail!"

Small and tidy and dignified, she does look remarkably out of place at Rikers Island. Although Holzer's age is as slippery as any of the other facts of her life, she admits to being fifty-six, her lawyers say she told them privately that she's sixty-two, and the prosecutor who put her away this time around guesses that she is really in her late sixties. Almost all the other inmates are black or Hispanic and young; the girls—many of them are still girls—call her "Miss Adela," and even her crimes set her apart. Most of the other inmates are there for drugs, murder, arson, robbery, prostitution. Holzer's fastidiousness is wildly incongruous amid the chaos and menace that surround her at the Rose M. Singer Center, a squat dusty-rose-colored building that might be a particularly ugly high school were it not for the metal detector at the front door and the arsenal in the banana-yellow lobby where correction officers must check their weapons and ammunition. Pass through the electronic gates just beyond and you are immediately assailed by waves of noise; from the exercise yard to the cellblocks, in the hallways and common rooms, people always seem to be yelling, whether in argument or agitation or high-pitched delusion of one sort or another. Holzer complains bitterly about the noise; the women scream all night, she says, and she can never get any sleep.

In the receiving room, the intake-andoutflow center where inmates wait to be transferred or to leave the building for trips to court or the clinic and where new admissions shower and are examined by a doctor, the din is deafening. There are young women in every imaginable state of dress and undress lounging against the walls or sprawled on the floors, most of them either howling or smoking in sullen silence. One woman is retching into a sink. Tattoos are much in evidence. Clothing and underwear hang from the bars; see-through plastic trash bags containing each individual's possessions are strewn around the cells. A sign on the wall reads, HAIR PIECES OF ANY KIND ARE NOT ACCEPTABLE IN OUR INSTITUTION MUST BE PUT IN YOUR PROPERTY IF NOT WILL BE THROWN AWAY. A hairpiece could be used to strangle somebody or to hide contraband, although the endless ingenuity of the Rikers Island clientele is more than a match for such rules; crack vials are routinely found hidden inside cheeks and vaginas, in ears or under eyelids.

Despite the grim cells of the receiving room, most of the time inmates are surprisingly free to come and go in other areas, except for the three times a day when they are locked up in their cells and counted. Only the ubiquitous banana-yellow grates, sliding silently back and forth in the halls, attest to the invisible monitors that limit the movements of the residents. Modern research has determined that inmates maintain a more positive frame of mind when incarcerated in an environment painted in bright colors rather than dreary institutional drabs, so the Rose M. Singer Center is tarted up in a startling array of apricots and tangerines, salmons and assorted yellows. In the big central exercise yard, women play basketball or volleyball, jump rope, or lie on the benches sunning themselves. They wear sweatpants or jeans, leotards, and T-shirts; the scene is oddly like a playground. In the school, inmates who wish to do so can earn their G.E.D., but education here is a difficult business. Holzer threw herself enthusiastically into tutoring one young woman who expressed an interest in the geography of the world, but no amount of effort could convince her pupil that Germany was not a part of Africa, a conviction the young woman implied was a function of Holzer's advanced age and whiteness.

Race and age, education and experience—virtually every aspect of her being isolates Holzer, a much-traveled immigrant who has always adapted readily to foreign countries. Some of the things the other inmates have taught her are useful: When you want a special treat, you buy cheese and salami and a roll at the commissary, wrap it all in a Kotex, and steam it over a pot of boiling water. When you need scissors, which are forbidden, you use matches to burn through what you want to cut. Use toothpaste as glue. Tear up a bedsheet to make yourself a sarong. Other practices are less relevant to Holzer's needs: The young women make jewelry out of paper clips, painting them with nail polish and sticking them through the holes in their ears or the perforations they have made in their noses with needles. They take the bristles out of a toothbrush and insert a razor blade to make a weapon that can slash someone's face in an instant. They bleach their hair with lye siphoned from the sanitation crew's supplies, or they throw it on one another in fits of rage.

Holzer tries to keep a safe distance; despite her Spanish descent, the intermingled strains of the Latin, Caribbean, and African traditions that have molded many of her fellow prisoners are quite alien to her. A lot of them believe in witches; they keep sour milk in their cells to bring them luck, and they let seven apples rot—these represent seven African powers, they tell her—to take the bad spirits away. They bum incense and candles and pray before them: "Get me out of La Roca," their name for Rikers Island—The Rock. They call Holzer the Picture Lady, because she takes photographs with a Polaroid, but if they don't think the results are flattering they accuse her of giving them an evil eye to make them look bad. To many of them Holzer, with her fair skin and elegant aloofness, is an exotic; one woman poked a finger in Holzer's eye to see if she was wearing tinted contact lenses, because her eyes are blue-green instead of dark. For the most part she tries not to involve herself in their incessant quarrels and the byzantine ins and outs of their relationships, which are highly volatile. Sometimes the fights literally spill over onto her anyway: Holzer says one woman bit off another's nipple and blood splashed all over Holzer's foot, conjuring up terrifying visions of AIDS, since so many of the inmates are HIVpositive. Then there are those who reach out to her in need. Desperate for connection, the inmates, most of whom lack cohesive families, invent relationships with other inmates: This one is my cousin, that one is my husband, this one is my wife. They stage weddings in the yard, carrying paper flowers, wearing white sheets, and throwing rice on themselves; someone holds a Bible and says, "Do you take this woman to be your wife?'' and the "groom" says, "I do." Inevitably, Holzer's age and carriage confer authority in a population where many of the young women still suck their thumbs; more than a few refer to her as "my mother," and seek her out to tell her their troubles.

Her own troubles she keeps to herself. H What could these young women hope to understand of her life, of what she has gained and what she has lost? The aristocratic upbringing in Spain, when she was surrounded by governesses and tutors and her own personal maid. The highlife in a succession of grand homes— the Fifth Avenue apartment, the town house on East Seventy-second Street, the estate in New Jersey with its pool and its tennis court. The private secretary who had worked for Babe Paley. The china collection rumored to have belonged to Catherine the Great, the bed said to have been slept in by Chopin, the paintings supposedly by old masters, the racehorse. The accolades from news organizations such as The New York Times, which called her "Broadway's hottest producer." The friendships with Jules Feiffer and Joe Papp, Terrence McNally and Murray Schisgal, Tom O'Horgan and Dustin Hoffman—names to conjure with in the New York theater, certainly names to titillate potential investors at dinner parties.

She had started as an investor herself, but after scoring with Hair, Lenny, and Sleuth, she wanted more. By 1975, Holzer had produced or co-produced three hits on Broadway—All Over Town, The Ritz, and Sherlock Holmes. She had long since perfected the art of impressing people with her rapid-fire patter about the dazzling array of deals she seemed to be masterminding all over the globe—the Toyotas she was importing into Indonesia, the trucks in South America; the real estate she was buying and selling in Spain; the trade in cloves and sugar, oil and cement, scotch and soap, copra oil and rice, tobacco and Parker pens; the Bolivian bank she coowned; the fish-meal factory in Peru. It all went up in smoke after she was arrested that first time; her third husband, a shipping magnate, divorced her, and her much-vaunted possessions were dispersed through the bankruptcy courts. It turned out that maybe they weren't so valuable after all; when the contents of Holzer's town house were auctioned off to pay creditors, art and antiques collectors thronged to examine her treasures, only to be disappointed by what The New York Times called ''the poor quality of the collection." As usual, Holzer's hype had been more impressive than the reality.

One woman bit off another's nipple and blood splashed all over Holzer's foot, conjuring up terrifying visions of AIDS.

By then she was serving time; the road back led from Rikers Island to the women's correctional facility in Bedford Hills, New York, through a halfway house in Harlem, and then on to a fundraising job at the Public Theater. The job, a condition of her parole, was made possible by a benevolent Joe Papp, who later said that Holzer spent a lot of time on the phone but "didn't raise a penny." However, she did manage to spin a new set of dreams, and soon she was persuading a whole flotilla of investors to buy into her ostensible deals in oil and gold, sulfur and precious metals. There always seemed to be new fish to hook, and before long there was a new Broadway show. Tom O'Horgan had two new "pop'ras" (pop operas) she was determined to bring to Broadway. The one she pinned her hopes on was called Senator Joe. "I was so sure this project was a winner," she says. ''The play would have been a tremendous success. My aim was always to help the American theater." Holzer continues to maintain that if a few of her investors hadn't gotten nervous about their money and sicced the district attorney's office on her everyone would eventually have gotten paid back and she would have won a Tony Award. As it was, frantic investors lost their life savings, their children's education money, the security of their homes; once again, Holzer lost her freedom.

And yet she still clings, with astonishing tenacity, to the tattered remnants of her dreams. According to the district attorney's office, when investors got worried, Holzer reassured them by confiding that she was romantically involved with David Rockefeller Sr., who, she said, supervised her deals and would make good on any investments that ran into difficulty. To some, she indicated that she was secretly married to Rockefeller, whose picture she displayed in a silver frame on her bedside table (a photograph the D.A.'s office later said had

been cut out of a magazine). The suspicious few who pressed her might eventually be shown letters and the presumed marriage certificate attesting to their union. These are remarkable documents, in part because they are so crudely executed and so full of typos and misspellings that it is incredible to think they ever fooled anyone. Chris Prather, deputy chief of the Frauds Bureau of the district attorney's office and the prosecutor in the case, says his investigation showed that Holzer began trying to get a piece of Rockefeller stationery as early as 1982. Several letters to David Rockefeller Sr. were unavailing, so she wrote to David Rockefeller Jr., recommending someone she admired as a guest conductor for the Boston Symphony Orchestra, on whose board he sat, and got a reply on his letterhead. According to Prather, she changed the "Jr." to "Sr.," whited out the text, and proceeded to spin off an amazing series of letters from her ostensible beau, verifying her investments and inquiring after her welfare. In one, dated December 16, 1988, Rockefeller supposedly wrote, "I was very glad to hear from you last night. Don't worry, you can call as many times as you wish. I am worried. You seem to be under tremendous pressure. Why? You have produced shows before and you know how difficult it is. I hope that you can come with me to St. John on the 28th. Take good care." The sign-off is "Until Wednesday night!"

Also in the Holzer file are two forged marriage certificates, one dated 1983, the other dated 1987. According to Prather, Holzer led investors to believe that she and Rockefeller had been involved since 1954, when she first came to this country from her native Spain, and that their relationship had lasted through her various marriages.

In her conversations with me, Holzer —who is erratic at best, talking nonstop in her fractured, Spanish-accented English and jumping from subject to subject in a kind of mesmerizing stream-ofconsciousness monologue—is typically elusive about her "relationship" with Rockefeller. One time when I bring it up with her, she acts indignant about the prosecutor's claims. "I still don't understand who came up with these fantastic stories!" she exclaims. "I never saw this marriage license!" But another time when I bring up the Rockefeller involvement, she hints as broadly as if I were a prospective investor to be seduced. "It was a friendly relationship, but I'm not allowed to say more," she says coyly. Not allowed by whom? "By him. He doesn't want me to talk about it—but you can't say that, because then I am a traitor to him." Has she been in touch with him? "Sporadically in touch." With Rockefeller himself? "With parts of the family, not with him." Will they resume their relationship when she gets out of prison? She doesn't know, she sighs: "The scandal was awful." Indeed it was, but, according to Chris Prather, David Rockefeller Sr. has never met Adela Holzer and had never heard of her until contacted by the district attorney's office. "To say he doesn't know me, it's a very shocking thing, but people want to lose their memory when they feel like it," says Holzer sadly, shaking her head. And the picture beside her bed? "Yes, I had a picture, but it was not a magazine picture, the way they said in the press," she retorts. Then, waving her hand imperiously, she dismisses the whole subject of David Rockefeller. "I don't want to discuss this affair at this point."

The Rockefeller connection is hardly the only thing Holzer has apparently lied about over the years; indeed, according to many of her former friends and associates, her entire life story is a veritable tissue of lies. She usually claims to have two or three sons, although she has often introduced the oldest one as her stepson from her first marriage, since his fiftyish age makes her own assertion that she is fifty-six decidedly problematic. In fact, she has five sons; she abandoned her three children when she left her first husband in Spain and moved to America, pregnant with her fourth child.

When I finally confront Holzer about the varying number of sons she has claimed to have in different conversations with me, she admits there are five and says she had to leave her first three behind when she came to America because she couldn't get a divorce in Spain. For years her first husband wouldn't let her see her boys. "It was so painful I just buried it," she says huskily. "I couldn't talk about it."

When investors got worried, Holzer used to reassure them by confiding that she was romantically involved with David Rockefeller Sr.

Those who know her well are unmoved by such heart-rending tales. "If she told me the sun was shining, I'd go out to look—and I'd take an umbrella," says Michael Alpert, a theatrical press agent who represented Holzer during the 1970s and who is now writing a book about her.

This is a widespread opinion, one certainly shared by Prather. "She's a con artist," says the prosecutor. "I don't believe anything she says. Is she a menace to society at this point? She certainly, in this case, hurt a lot of people very badly. Hopefully, when she gets out, she'll be incapable, from age and reputation, of doing this again—but I don't know."

T here is only one road to Rikers IsI land. It ends in what the cops call the I Queens abutment, a grim little hump of land covered with scraggly brush where a squat guardhouse blocks the way to the narrow bridge providing the only access to the vast prison complex on the other side. Just across a brief stretch of the East River, a waterside runway at LaGuardia Airport looks so close you could almost touch it. On the Francis R. Buono Memorial Bridge, which is lined with loops of razor wire, you need a slew of passes and identification badges just to drive on to the next checkpoint. Once you arrive on the island, all you can see, in every direction, is acres of low, mean-looking buildings, girded by fences topped with miles of razor wire glittering in the sun.

The planes take off from LaGuardia every minute or two; the prisoners in the exercise yards never look up, even if only to dream for a moment of other places and different fates. Adela Holzer has always been a dreamer, imagining distant lands and better lives; over and over again, she has re-created herself, concocting new identities and new careers, finding new husbands, adding new names, imagining new futures.

Holzer has spent the last year on the move again. After five hundred days at Rikers Island, she was finally transferred to the women's prison in Bedford Hills, and thence to the upstate facility at Albion, near the Canadian border. Now she is gearing up for the next phase, in which the phoenix will rise yet again from the ashes of her past.

As Adela Sanchez Lafora Castresana Duschinsky Holzer, she has often told the preferred version of her history, the one in which she came to America and made her way as a teacher at Columbia, as a translator at the United Nations, as a shrewd international businesswoman. She has also held fast to her status as a well-bred lady tragically out of place among the criminal underclass in prison. It turns out that perhaps Holzer is not as much of an anomaly there as she would have one believe. It seems that she was arrested at least once for prostitution back in her early years in New York, when she was allegedly working as a call girl and made the mistake of soliciting an undercover agent. For twentyfive dollars, she offered to commit an "unlawful act of sexual intercourse," according to the complaint filed by the officer, and proceeded to disrobe, whereupon he placed her under arrest. The year was 1963; she gave her age as thirty-four, which, if true, would make her sixty-two today. Holzer's version of this story is typically impassioned, selfserving, and farfetched. She says a cop visiting a call girl next door pulled a gun on her and demanded she make love with him. When she refused, he arrested her. "I was a victim!" she says. A judge later dismissed the charge.

Holzer has never been less than enterprising about different ways of earning a living, and her imagination hasn't flagged. She is writing two books, she says, one a biographical account of what has happened to her, the other a novel. "The biography is the one that is going to give me the big money," she says. And there are so many other things she can do. An advertising agency wants her; they think she has great ideas. She can always buy and sell art: "lam very good in art," she assures me. She could work with government grants. She might even direct a little Off Off Broadway play. People are offering her all kinds of jobs. "I can do a lot of things," she says. "Nothing is final in life; I have started again a number of times. "

Her singsong voice is hypnotic; she is funny and smart and often touching, and it is hard not to be charmed by her. The endless inventions are mesmerizing, after all, and one finds oneself thinking, Surely she couldn't be making all of this up! Surely some of it is true! But as she talks I keep thinking back to one of our earlier visits at Rikers Island.

We are sitting on the little children's chairs behind the yellow wall of bars, and Adela is talking about how effortlessly she has always been able to draw people into her life. Her face-lift was a good one; despite the inevitable tightness around the mouth, she is still pretty and vulnerable-looking.

"For me, it's very important to create," she is saying earnestly. "I want to work; I love to work; I have to work! I will have to start over from scratch."

Then she looks me straight in the eye, and for a moment the cold steel of her determination glints through. "People underestimate me all the time," she says. "I attract people; they come to me.

I think people care more for me than I care for them. I never get attached. People say I'm cold. I don't think I'm cold. I'm very careful not to get too close to anybody." She shrugs, as matter-of-fact as if she were discussing the certainty of the sun's coming up in the morning. "I make new friends very easily. I'm sure I will find people."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now