Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE IRAN-CONTRA SHOW

A new book reveals how the congressional investigation became a made-for-TV circus

HAYNES JOHNSON

Politics

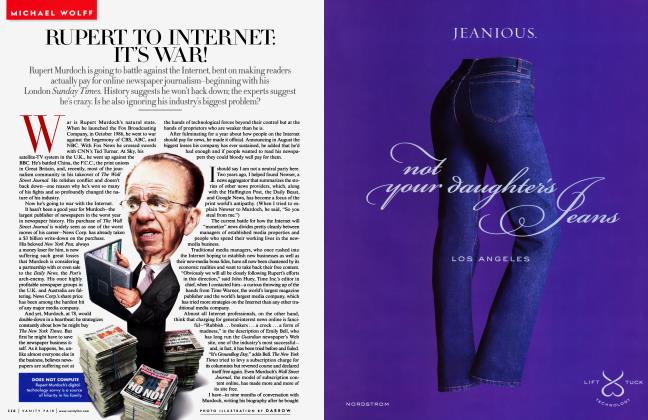

The phone call from Washington came in December of 1986 as Arthur Liman was preparing to try a case involving Impressionist paintings for Christie's in New York. In his painstaking style, Liman had been talking to experts about Monet and Manet and learning how to pronounce "Van Gogh'' properly when his secretary said that Senator George Mitchell was calling.

Liman was not a Washington type; he didn't know Mitchell personally, and only barely knew his name. The senator was direct and brief. Would Liman come down to Washington and talk with a select group of officials about the possibility of directing the U.S. Senate's investigation into the unfolding Irancontra affair? Liman said he didn't think he was the right person for that task. but he would be happy to discuss it.

Liman, one of America's leading criminal lawyers and an expert on securities law, had followed the arms-sale news with special interest. It was obvious to him, as he watched Attorney General Edwin Meese's television announcement about the diversion of the proceeds from the sale of arms to Iran to fund the contras, that the government had been involved in a sordid operation. He wondered whether it was possible, as Meese had suggested, that a Marine lieutenant colonel on the National Security Council could have done all this without the president's knowledge.

He was still mulling over that question, and many others involving the secret arms-for-hostages deals, as he traveled to Washington to meet with a group of senators in George Mitchell's office.

Though Mitchell had never heard of Liman before the Iran-contra investigation began, Mitchell's colleague Senator Warren Rudman, who would serve as vice-chairman of the Senate committee, knew about him. Rudman had read Liman's law-review pieces, had heard him speak, and admired him as being among that select class of American attorneys that could accurately be described as "superlawyers.''

Liman immediately told Rudman, Mitchell, Howell Heflin, and the few other senators present that he thought their investigation faced major problems. First, he said, Reagan enjoyed great popularity. Second, even in liberal New York City, people were not preoccupied with the Iran-contra affair. Furthermore, Liman said, his experience had taught him that when you are dealing with evidence controlled by subordinates of a chief executive you never have any assurance you will get the truth. Everyone tends to be protective of superiors. Besides, in this case they faced the additional burden of dealing with Swiss bank accounts, and he told them of his experience in trying to penetrate Swiss secrecy. All in all, it was going to be a most difficult investigation, and they were likely to be caught in the middle. They would be accused both of failing to disclose the full story and of persecuting the president for political purposes. Liman said he didn't envy them.

As for himself, two things should make them hesitate about even considering him. He had no prior Washington experience, and there was much to be said for having a lawyer well versed in the ways of the capital. His greater concern, he went on, was the fact that he was Jewish. Would that influence the way he conducted the investigation? they asked him. No, he said, but appearances are important. "I think you will never satisfy people that a Jewish chief counsel could do the job objectively.' '

This remark touched off a strong reaction. From the way the senators spoke, Liman felt they thought him almost unAmerican. "Well,'' Rudman said, "I'm Jewish!" Liman was surprised. He had not known.

Excerpted from Sleepwalking Through History: America in the Reagan Years, by Haynes Johnson, to be published this month by W. W. Norton & Company.

Liman explained that everyone knew Israel had been involved in the arms sales and questions were being raised in the press, planted and encouraged by the Reagan administration, about whether the diversion had been Israel's idea. If the investigation failed to document Israel's role clearly, would it be said that Liman had tried to whitewash Israel because he was a Jew? If he came down hard on Israel, would he be accused of trying to prove that he was not inhibited by being Jewish? Either way, it was a problem. The fact that he was Jewish was a factor. The senators would not hear of it: if support for Israel was a disqualification, they told him, then they ought to disband the committee.

The session ended with Liman being impressed by the senators, and the senators by him. Much later, Mitchell realized that they had never considered one factor that might influence public judgment on the investigation: how would Arthur Liman come across on television? No one had raised that question, or thought to weigh the impact of personality on the televised inquiry they would conduct.

1% ack in New York, Liman quietly K sought the counsel of the people he wM most respected. Foremost among them was his senior law partner, Simon Hirsch Rifkind. Liman revered Rifkind, a Russian Jew who had become a naturalized citizen in the mid-twenties, and an ardent New Dealer whom Franklin D.

Roosevelt appointed to the federal bench in New York, where he had a distinguished career before returning to private practice.

Rifkind urged Liman to accept the committee job if it was offered. There are some calls you cannot reject, he said. This was such a call. Liman owed this service to his country. Another of Liman's partners, Theodore Sorensen, former special assistant to President Kennedy, gave similar advice.

A third person whose advice Liman valued highly strongly disagreed. William S. Paley, board chairman of CBS and for years the most influential person in U.S. television, urged Liman not to accept if asked. Paley had spent all his life in the media, he reminded Liman, and this situation involving Reagan and Iran-contra was going to be exceedingly difficult. This is a very, very popular president, he said, and you're going to be crucified if you take on that job. Paley repeated his warning: You're going to be crucified.

But when Mitchell called to offer Liman the job, he accepted and immediately went back to Washington, where he had a brief, but intense, conversation with Committee Chairman Daniel Inouye. Inouye stressed his desire that the committee be bipartisan. He had been in Congress nearly thirty years, Inouye said, and his experience was that whenever a president was under attack it invited adventures by the Soviet Union. Therefore, he said, it was important for this problem to be resolved quickly.

Mitchell was convinced North was bluffing; he opposed meeting North's demands.

If the evidence demonstrated that the president should be removed, then he should be removed promptly and America would get a new president. If the evidence didn't warrant his removal, Inouye added, then we should end this investigation, report the facts, and let the country continue with its business. In the months to come, this was a consideration that Inouye and Liman discussed privately on at least a dozen occasions, and Inouye consistently expressed the same philosophical point of view: the one thing the country could not endure was to have a president so crippled that in effect no one was in charge.

The clock favored the president. When the investigation began, Reagan was entering the last phase of his second term in office. By the time the congressional investigation and hearings were finished, another presidential election cycle would have begun. Thus, everyone involved in the investigation felt the need to complete the task quickly. If there were to be an impeachment proceeding, it would come at the very end of Reagan's presidential tenure.

This was the opposite of the Nixon impeachment crisis, which had begun building immediately after his second inaugural, but Watergate had left its legacy: the public had been conditioned to look for a "smoking gun" in deciding whether to impeach a president. So, with Reagan, attention focused almost exclusively on one question: Had the president approved the diversion of Iranian arms-sale funds to the contras? The diversion was never the most significant aspect of the secret Iran-contra activities, but from the moment the White House announced that it had occurred, it became the topic that dominated press reports and political debate. In a real sense, near-exclusive focus on the diversion was itself a diversion.

With that issue in mind, Inouye told the committee privately that he was opposed to any move to subpoena the president or Vice President Bush. Nor did he wish to issue an invitation for them to appear. If they declined, and word got out, unbelievable pressures would be placed on the president. His ability to lead and govern would be irreparably damaged.

Admirable as Inouye's attitude was, especially in the concern for fairness, at heart it was an Old World view of politics and leadership—the view of an insider who lacked the taste for a difficult conflict and sought to reconcile rather than confront. He did not bring to his task the passion and indignation of, say, Sam Ervin during the televised Watergate hearings. It was Inouye, for instance, who prevailed in acceding to the terms imposed by Oliver North's attorney, Brendan Sullivan Jr., for North's public testimony. North's position, as articulated by his lawyer, was that he would refuse to appear unless granted immunity from criminal prosecution for congressional testimony that he might give. Sullivan also demanded that the committee limit its questioning of North both in number of days and hours per day.

George Mitchell, for one, strongly opposed meeting North's demands. He was convinced that North was bluffing, that in fact North wanted to testify because it would give him an opportunity to publicly vindicate himself.

Inouye and others felt equally strongly that the committee had no choice but to agree to North's demands. A cloud unfairly hung over the president's head, they argued, and Congress had an obligation to determine as quickly as possible what Reagan's role had really been. That could not be done without the testimony of Oliver North. Furthermore, the congressional bodies had pledged to complete their investigation by October. If North continued to refuse to testify, their*only recourse would be to institute contempt proceedings and compel him to testify or go to jail. Those proceedings would probably drag through the courts for months. Inevitably, a more divisive and destructive partisanship would result as the investigation became enmeshed in the presidential politics of 1988.

This, at least, was the view of Inouye, Rudman, and others, and they won. The question never even came to a private vote. North's demands were met. Mitchell remained troubled and doubtful. "I'll always to the day I die wonder w'hat -would 'have 'happened 'had 1 pressed it to a vote and we'd prevailed,'' he said. "I still think North would have testified.''

I ohn W. Nields Jr. was frustrated. AfI ter two months of intensive work that 3 began formally on January 10, 1987, he wondered if they were ever going to get their investigation off the ground. As Liman's counterpart for the House committee, chief counsel Nields had immersed himself in seven-day-a-week sessions that seemed to last around the clock. He had hired staff and investigators but was still unclear on the scope and complexity of their investigation. In the beginning, all they had was a box of newspaper clippings, and no paper clips. For two months they didn't even have offices. They couldn't get security clearances or physical custody of documents they sought. It was taking, Nields realized glumly, a shockingly long time to gather their basic material.

Nields, whose long hair and lean, youthful looks made him resemble a sixties student in a Brooks Brothers suit, was a lawyer with considerable prior experience on Capitol Hill. He had been fully aware that his committee assignment would'be difficult and demanding, but now he was beginning to doubt his own abilities.

When the so-called Tower Commission report had been issued on February 26, its findings were regarded as highly critical of Reagan. In fact, the conclusions of the commission, which Reagan had appointed, contributed strongly to a public impression that he had been a victim of his own inattention and lax "management style." While the report criticized the president for putting "the principal responsibility for policy review on the shoulders of his advisers," and said Reagan "must take responsibility for the [National Security Council] system and deal with the consequences," it left the impression that Reagan was more victim than victimizer.

This portrait of a detached, uninformed, inattentive, passive Ronald Reagan fit with the image the public had already formed of the president and was, in the context of the Iran-contra affair, a political plus. Reagan simply hadn't known what was happening. Others had.

The Tower Commission report made Nields's job all the more difficult. By March, the deadline for public hearings was fast approaching, but Nields still felt he didn't have a grasp of the subject or where it was heading. He lashed himself for failing to do the job properly. In that frame of mind, he asked his investigatory staff to pull together all the significant material they had gathered so he could read it and prepare a private briefing for the full House committee.

As he began reading, two things immediately hit him: the altered documents that North and National Security Adviser Robert McFarlane had prepared and McFarlane's letters to Representatives Lee Hamilton and Michael Barnes falsely claiming that no National Security Council members were involved in assisting the contras. "Looking at these things as an investigator," Nields said, "I was absolutely flabbergasted. I could not conceive of someone writing those letters to Congress. To me it was a shocker."

He read on, and grew even more disturbed. Committee investigators had uncovered computerized "PROF" messages that North thought he had purged. They were damning. Nields could hardly believe what he was reading as he studied messages between North and Admiral John Poindexter, McFarlane's successor as national-security adviser, about the November 1985 Hawk shipments juxtaposed with t'he false secret testimony about oil-drilling equipment that both C.I.A. Director William Casey and Poindexter had given before the congressional intelligence 'committees. "Again, I was shocked," Nields said. "I just didn't think I would ever find national-security advisers participating in that kind of a fraud. That was the point at which the whole thing changed for me. I had a totally different impression of what we were doing and what it meant, what conduct we were likely to find. The way I thought of it was that it was my government that was being dishonored and deceived. That's what shocked me. The dishonesty hit me a lot harder than the diversion. I don't understand why it didn't hit other people harder."

Nields gave an evenly stated private briefing of these preliminary findings to those members of the full committee who showed up. (A number did not.) Carefully, nonjudgmentally, he stressed the factual conflicts between what Reagan officials had said privately among themselves and what they had claimed both in secret congressional testimony and public comments. The absence of much reaction from the committee further frustrated him. Nields had the feeling he hadn't captured their interest, and he wondered if perhaps he himself had misunderstood the seriousness of the material. Maybe it wasn't as important as he had thought. Maybe he needed to work harder.

arren Rudman was nervous. He had administered the oath to Admiral John Poindexter amid m circumstances melodramatic for their secrecy, and then returned to his Senate office. Now he was waiting, and waiting, and waiting.

It was Saturday, May 2, 1987, three days before the congressional hearings were to begin, and Poindexter's deposition was being taken upstairs. Until that moment, no one had known what Poindexter would say, under oath, when asked whether Ronald Reagan had authorized the diversion of Iranian armssale funds to the contras. Many believed he would say the president had been fully briefed on all such matters and had approved the actions of Poindexter, North, and other N.S.C. operatives. At earlier congressional hearings, his refusal to answer questions by taking the Fifth Amendment strongly suggested that he had knowledge damaging to the president.

From the beginning, Rudman had held the view that the diversion was the crucial problem. Selling arms to the ayatollah was dumb, but if the president had approved the diversion of the proceeds, it was an impeachable offense. John Poindexter held that key.

Rudman had studied Poindexter's background. The admiral's commanding officers described him as a perfect subordinate, a painstaking officer with a formidable memory, who paid meticu-

lous attention to detail and procedure. Poindexter always carefully briefed his superiors and was noted for his desire to bring any possibly troublesome matter to their immediate attention. Was it conceivable that such an officer—who had graduated first in his class from the Naval Academy and held the numberone leadership position in the brigade of midshipmen—would not have brought to the attention of the president of the United States any matter that might create problems for him and the nation?

To ensure maximum secrecy, Poindexter's deposition was being taken in a specially constructed ninth-floor Senateoffice-building security vault called "the bubble." With panels of aluminum on the outside, and an air-conditioning system composed of special "sound baffling" materials, it was so secure that laser devices could not penetrate it. The C.I.A. used something like it for its special interrogations, and this bubble, like theirs, was filled with sophisticated electronic anti-bugging devices.

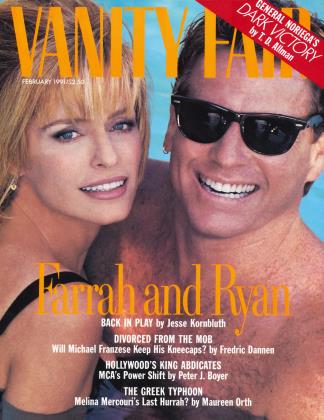

William Paley warned Liman You're going to be crucified if you take on that job.

Rudman, representing the Senate committee, and Thomas Foley of Washington, representing the House, had led the small group into the eight-by-fifteenfoot bubble. The big, heavy door closed behind them. They proceeded to the long table in the center of the room and administered the oath to Poindexter. Then Rudman and Foley departed, leaving behind Liman, Nields, Poindexter, his lawyers, and a stenographer.

Unless Poindexter's testimony presented major problems for the president, his deposition would be sealed and not made available to any members of the committees. If Poindexter did offer explosive testimony about Reagan's role, Daniel Inouye had promised, he would inform White House Chief of Staff Howard Baker immediately, and privately. Inouye wanted to make sure that the White House and president would be prepared for another looming impeachment trauma. As he left the bubble, Rudman thought, Today we're going to find out whether or not Ronald Reagan is going to finish out his term.

He waited for hours without word of what was taking place upstairs inside the bubble. An entire day passed. Still no word, no signal. Finally, he could stand it no longer. He went upstairs and arrived just as Poindexter was leaving. John Nields was walking out, too.

"Hi, John," Rudman said. "Hi, Warren," Nields answered. Nields kept on walking without saying another word.

Rudman entered the bubble. "How're you doing, Arthur?" he said to Liman. "Fine," Liman said. Liman told him that they were going to have to continue with Poindexter's testimony for another day. "O.K.," Rudman replied. He paused, then asked, "Anything you want to talk to me about?" Liman said no. Fine, Rudman said. At that moment, he knew there would be no smoking gun. The admiral had absolved the president.

ust weeks after beginning his investigation, Arthur Liman had come to a conclusion about the case: The Tower board's findings about Ronald Reagan were completely wrong. The board had, as Liman put it, concluded that the president was essentially like a child who needed a nursemaid. The reason Reagan made those mistakes, their theory went, was that he didn't have the right nursemaids. Secretary of State George Shultz, Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, and Chief of Staff Donald Regan were all the wrong people for this president. They hadn't been forceful enough; they hadn't brought matters to his attention; they hadn't objected strongly when they learned of covert operations running wild.

That theory was a fraud, Liman decided, "not a deliberate fraud by them, but a fraud when it came to Iran and the contras." It had not been a case of Shultz or Weinberger failing to argue hard enough with Reagan, or of the president missing the point they were making. Reagan knew what he was doing, Liman came to believe; he had been in charge, even if he operated with disdain for the law.

For the first time, it struck Liman that what he was seeing was another manifestation of what Reagan had done repeatedly over the previous seven years, in his environmental appointments, in his ideological battles over the Legal Services Corporation, and in a host of other domestic areas. When the president didn't approve of a law, he simply didn't execute it. Instead, he impounded funds or appointed people hostile to the purposes of the regulatory agency or government department they were to head and ideologically opposed to the laws they were supposed to enforce.

In the notes of Reagan's interview with the Tower Commission, the president stated he didn't know that his National Security Council staff had been supporting the contras. Soon, however, Liman learned that Reagan had received a pledge of $25 million to assist the contras directly from King Fahd of Saudi Arabia when the two leaders had met alone in the White House family quarters. Moments after this meeting, Reagan briefed Shultz and McFarlane on what had happened, but made no mention of money for the contras. McFarlane later learned this momentous news from the Saudi ambassador. Shortly thereafter, the money was in McFarlane's hands, and it became his responsibility to see that it was deposited in Swiss accounts for the contras.

Liman was convinced that the Iran arms deal had turned into something different after initial attempts to free the hostages failed. The Americans realized that they were not, in fact, dealing with "moderate elements" and that prospects for freeing the hostages were dim at best. At that point, Liman believed, Casey, Poindexter, and North continued to support the sale of U.S. arms to Iran because it would generate a huge "black operational" fund for a number of special covert operations.

To Liman, the fragments of Reagan's diaries that he read made clear Reagan's strong wishes and personal involvement in illegally supplying the contras. Liman concluded that, however misguided, however wrong, Ronald Reagan had acted like a president—a strong, bold, risktaking president, not a detached, passive, uninformed one.

It was more difficult to prove Reagan's direct involvement in the armssale fund diversion. Casey was dying, unable to testify, pertinent documents had been destroyed, and there were doubts about the critical testimony that Admiral Poindexter and Colonel North might give.

Liman misjudged both men. Poindexter struck Liman as a man strongly indoctrinated by the Naval Academy code of honor. A number of Poindexter's military superior officers reinforced that impression. They explained that there were different kinds of staff officers. Some will run with the ball, try to be manipulative, and operate in a political manner. That was not what John Poindexter was like.

Although Poindexter had already taken the Fifth before another congressional panel, Liman hoped to create an opportunity that would get him to talk. Liman arranged for a private meeting between Daniel Inouye and the admiral before the committee granted immunity. He had hoped the two principals could meet alone, just the chairman and the admiral, but in the end Poindexter's counsel, and therefore Liman, attended.

It hurt him, Inouye began, to see a man in uniform taking the Fifth Amendment, and he spoke about his pride in the uniform and what it represented. This had to work, Liman thought. He appreciated, Inouye continued, that Poindexter had all the rights of a citizen, but sometimes you were thrust into a position in which you had to be willing to waive those rights. That's what the country expected.

It was both surrealistic and disturbing: Oliver North, self-appointed superpatriot, endlessly writing into a void.

Poindexter's face was hard to read. Listening to Inouye, he did not seem disturbed. He looked steadily at Inouye the entire time. When it was his turn to speak, he simply said, "I'm not going to wear my uniform."

Liman was astounded. It seemed clear to him that Poindexter thought a plainclothes politician was free to do things that an honorable uniformed man of the navy was not. Without the uniform, Poindexter could tell whatever story he wanted. To Liman, that insight into Poindexter's character was one of the most poignant and powerful revelations of the investigation.

Still, as a professional interrogator, he thought he might be able to get Poindexter to be more forthcoming during their session in the bubble. After much thought, he decided that Poindexter would expect him to go immediately to the central question of the diversion. Liman did the opposite. He began his questioning at the end instead of the beginning, focusing on Poindexter's destruction of the signed presidential finding that clearly stated Reagan had approved a straight arms-for-hostages swap.

By questioning Poindexter on this area, Liman thought he might avoid a prepared reply—and just possibly might get the admiral to say things he had not intended. It did not work. Poindexter changed the subject and then quickly volunteered his version of the diversion. He hadn't told Reagan, the admiral said, because he was certain that Reagan would have approved the idea—enthusiastically. Poindexter wanted to keep this critical knowledge from the president so Reagan could honestly deny knowing about it if it became public.

During a break in the long first day of examination inside the bubble, Liman turned to one of the other lawyers present. Poindexter was like Billy Budd, Liman said. He was going to go to his death saying that he loved his captain. From that time on. Liman thought of Poindexter as the stout but doomed Billy Budd.

Liman remembered Poindexter telling him about his sons in the navy, one an Annapolis graduate. If Poindexter fingered the president, he might survive, Liman thought now, but he might destroy the careers of his sons. They would be regarded as Benedict Arnold's children. There, for Liman, was the essence of tragedy: an officer of distinction whose career would be destroyed because of his willingness to bend a historical fact in order to protect a president and save his sons.

Putting himself in Poindexter's head, Liman concluded that the admiral had been unable to say to the president, "It's your decision. You have to bear the responsibility for your actions. I must live by the code of honor that I am sworn to uphold. "

J| t first, Liman also felt he understood II Oliver North. People like North are n bond salesmen, he thought. They believe in what they sell and they ultimately go broke because they buy it. But the more Liman studied North, read his notebooks and PROF messages, and interviewed his close friends, the more he came to hold a different view. North was not the zealot that he was portrayed to be. Oliver North could have worked for almost any White House and done exactly what he did for the Reagan group.

Liman had seen many people like North. They could not distinguish easily between fantasy and fact. Their great strength was their total belief in their mission of the moment. He learned something else about North. Despite North's public claim to be willing to be the "fall guy'' in the Iran-contra fiasco, he had no intention of taking the fall.

In his testimony, North repeatedly pointed toward the president as the responsible character. It was North who kept insisting that he regularly and repeatedly sent memos up the chain of command for presidential approval, North who kept letting it be known that he believed every single act he had undertaken had been officially authorized. Once, North even volunteered damaging information about Reagan. He had stood near the president after a National Security Planning Group meeting, he recalled, and had then said aloud to Poindexter how ironic it was that the ayatollah was funding the contras. He didn't think the president had heard him, North said, but believed Poindexter would recall the conversation.

Why did North volunteer that? Liman wondered. No one had asked him about it. No one knew about the incident.

North appeared to be the kind of person who needed a father figure, a strong authority model. Liman believed that Bud McFarlane had originally filled that need. North even seemed to have adopted certain of McFarlane's personality traits, and his writings reflected them: a studied kind of intellectualism, the professional air of the important person who wrote significant policy memorandums for even more important people. Then North seemed to drop McFarlane, to lose respect for his old boss and former ranking Marine Corps officer. Maybe North found McFarlane weak, Liman thought, especially after McFarlane attempted suicide when the Iran-contra net was closing and his record of deceiving Congress was about to be exposed.

Next, North seemed to adopt as his role model Richard Secord, the hard-bitten retired general who became the private-operations officer for the Enterprise, that secret Reagan-administration entity formed by Bill Casey which carried out worldwide national-security missions without public accountability. Liman observed that North assumed a number of Secord's characteristics. Then, of course, there was Casey himself. That was perhaps the most complex relationship of all, though Liman was never as sure as others that it had been a father-son kind of relationship.

It was speculation, to be sure, this fathoming of character, but Oliver North was a remarkably revealing person. His notebooks were a gold mine. They provided leads for countless new lines of inquiry. To one of the committee lawyers, Bud Albright, they also contained a sense of the driven nature of the person he was investigating. As Albright read through the voluminous records, he didn't see how North ever got away from those notebooks. Everything was recorded in them: every meeting, every phone call, even, it seemed, every fragment of conversation. The same was true of North's prolific performance on the PROF computer electronic-mail-andmemo system. He recorded anything and everything that was happening. Often late at night, or into the dark hours long after midnight, North would still be writing his revealing personal messages. Sometimes they sounded like cries from the heart, or cries for support and understanding. He hadn't slept for two or three days, he would write, but had to keep on, had to keep trying, had to keep driving for the hostages. If anyone was listening, or receiving, he would say, offer the captives a prayer. It was both surrealistic and disturbing: Oliver North, self-appointed superpatriot, endlessly writing into a void.

McFarlane said in an anguished voice, You have no right to judge me, because you have never had to deal with this president.

In studying the North-McFarlane documents the investigators had uncovered, and after talking to North's secretary. Fawn Hall, Liman realized that McFarlane had written out the numbers of the documents that North had altered. The numbers were in McFarlane's handwriting, and McFarlane didn't know that the investigators knew that. Bud McFarlane seemed to offer the key to the case. Here is a man I can break, Liman thought. He has the whole story, he knows it all.

In that spirit, Liman conducted some "bloody'' interrogations of McFarlane. But McFarlane was not broken. The longer the questioning continued, the more McFarlane retreated into a fog of rationalization. Merely thinking about it later made Liman uncomfortable. But he had realized, when he looked at McFarlane during one of their private interrogations, that he had gone as far as he could go.

In the midst of an intense session. Liman felt great sympathy and admiration for McFarlane. It was when McFarlane turned to Liman and said in an anguished voice, You have no right to judge me, because you have never had to deal with this president. You have not been in sessions with this president where you describe this to him and you describe that to him and find that he has absolutely no interest whatsoever in those matters of policy. All he wants to do is talk about the contras. You don't have to deal with the ideologues in this White House. You don't have to deal with this president's uninterest in matters of real importance.

With immense frustration, McFarlane recalled how after the 1984 landslide he had asked Reagan to choose his main foreign-policy objectives. McFarlane gave Reagan a list of twelve objectives, asking the president to pick only two or three to ensure success. Reagan picked all twelve. Unless you were exposed to that kind of environment and those kinds of people, McFarlane said to Liman, his voice rising, you have no right to sit here and judge me.

A enator Bill Cohen had an inkling of ¾ what to expect when Oliver North w took the stand. The Maine Republican, though a supporter of Ronald Reagan's, felt the country was going to pay a heavy price for the administration's growing disdain for the law. Disrespect for national institutions was being created, making it ever more difficult to maintain ethical judgments.

Cohen knew little about Oliver North, but that little set off internal alarms. An attorney on the House Foreign Affairs Committee had told him of an earlier incident when North was called to testify before that committee. North and his attorney, Brendan Sullivan, were sitting in this man's office waiting for Admiral Poindexter to complete his testimony. North and Sullivan were discussing whether to demand that television cameras be banned when North was called to the stand. Like Poindexter, North would take the Fifth Amendment, and Sullivan did not want cameras present to record that moment. North was in an ebullient mood, joking, laughing, obviously at ease. "Don't worry, counselor,'' he said to his attorney, "I can handle it.''

With that, North walked into the hearing room. Immediately his demeanor changed. Instead of being cocky, lighthearted, cavalier, North suddenly appeared soulful, sad. His facial expression was one of pain and sorrow.

The House lawyer, in recounting this to Cohen, warned that Oliver North was highly capable of turning emotion on— and off.

North did both when he was finally called to the witness stand in the old Senate Caucus Room to begin six days of televised testimony in July. His eyes glistening with emotion, he "handled it" well. His demeanor sorrowful, his manner open, his voice husky and at times cracking with emotion, he was the wounded warrior willing to take, as he put it, "the spear in my chest" for mistakes that might have been made in the national interest. Dressed in his Marine uniform, his chest covered with ribbons and decorations, he was on the offensive, but not sullen like Secord, arrogant like Hall, or pathetic like McFarlane. He admitted to error, falsehood, obstruction, destruction of evidence, and all for a higher cause. "Lying does not come easy to me," he confessed. "But we all have to weigh in the balance the difference between lives and lies."

The country was enthralled by North. Here, at last, was a genuine hero. Even the childishness and bungling that typified much of his and the Enterprise's dealings were cloaked with a kind of exuberant innocence. The public learned a tantalizing new vocabulary. North called hostages zebras. The U.S. was Orange. Israel was Banana. Missiles were dogs. Nicaragua was Eden. Reagan was Joshua or Henry. The State Department he derisively tagged as Wimp. A secret Swiss bank account was Button. His wife, Betsy, was Mrs. Bellybutton. As for himself, Oliver North adopted the white hat. He was variously Mr. Goode, Mr. Green, Mr. White, or Steelhammer. Here, in the flesh, was a true secret operator, wearing medals no less.

It was a remarkable show, better than the soaps, many thought, and it was all live on television.

"Olliemania," as it was instantly dubbed in the press, gripped America. Flowers poured into the Senate for North. They were stored in a room near the hearing chamber. Telegrams of support flooded the Capitol. Sullivan shrewdly placed stacks of them on the witness table, where they could be photographed. Outside the building where North was testifying, large crowds of supporters cried out his name, Ollie, Ollie, Ollie. At a break in the hearings one day, North and his wife went to a Senate balcony and acknowledged the support of his legions by waving to them. The committee members reeled. Some stumbled over themselves to pay tribute to this American hero for the eighties.

The amount of hate mail and number of threatening phone calls Liman was getting increased by the hour.

But one night during his testimony, a different North appeared. Bill Cohen and a few other committee members held a late, closed session so that North could brief them on other covert operations in which the Enterprise had been involved. Cohen was struck by the dramatic difference in the atmosphere between the private session and the public ones, and he realized what a mistake the committees had made in staging the hearing. On television, it had appeared that the committee members were sitting high up on their platform like Roman potentates while down below the lone noble Christian faced the lions. In the small, private setting, without the TV cameras, it was an entirely different feeling—and a different North. This North was relaxed, casual, a storyteller approaching them as if they were in an exclusive men's club. O.K., fellas, here's the way it really was on the front lines, he seemed to imply, and he shared confidences and sought their approval. No speechmaking now, Cohen noticed, no little sermonettes of the kind he had been delivering before the cameras.

North profited from another structural problem inherent in the hearings. In the televised committee-hearing format, it was difficult for either the chair of the committee or the committee itself to seem impartial. Of necessity, the chair acted not only as head of the inquiring body—the committee—but also as judge. It was one more aspect that helped create an impression that power was arrayed unfairly against a single witness, and an especially earnest and compelling one. No wonder Americans were ignoring the disturbing truths that were being uncovered.

T or Arthur Liman the worst moment W came on the last day of his questionI ing of Oliver North. Nothing had been going well. House Republicans on the committee were openly attacking Liman as a partisan liberal Democrat biased against North and Ronald Reagan. They were interrupting his questioning, criticizing his tactics, playing to the cameras. And the amount of hate mail and the number of threatening phone calls he was getting increased by the hour. He wasn't worried as much about the threats—most of them, he realized, were from kooks—as about their effect on his wife, Ellen. Several years before, the Limans had been assaulted and nearly killed by a mentally disturbed person in New York. Memories of that traumatic experience were rekindled by the increasingly vicious threats Liman was receiving. Now the Limans had police stationed all night outside the home they had leased in northwest Washington.

North was still testifying when the panel broke for lunch. Liman had one more hour to go before turning the interrogation over to the committee. After a hurried meal, he returned to the Senate Caucus Room, which was still locked to the public. He walked into the room and was shocked by what he saw. There, lined up before the committee platform, was what appeared to be the entire Senate police force, along with some committee functionaries. In front of them was a Senate photographer. And standing in the center, posing like a president, was Oliver North.

One by one the committee functionaries and each member of the Senate security force moved forward toward North, paused to shake his hand, and posed with him for the photographer.

Liman gazed at the scene and couldn't take it anymore. He walked back into the anteroom behind the chamber and sat alone, his head bowed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now