Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

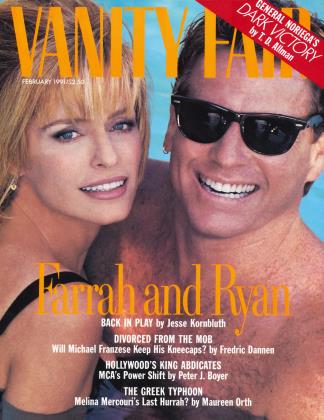

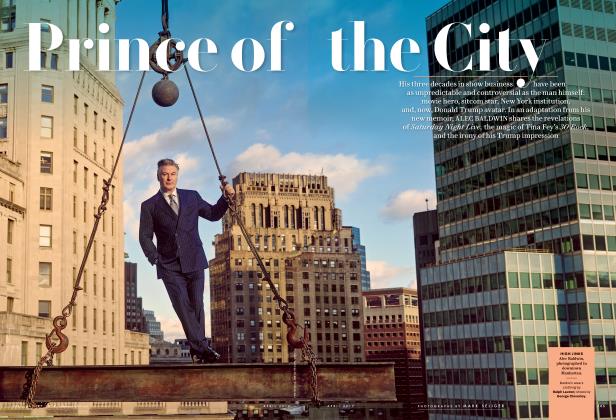

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAfter a decade of his own fame being eclipsed by Farrah Fawcett's ever rising star, Ryan O'Neal has talked her into bringing him back, on equal terms, with their new comedy series, Good Sports. JESSE KORNBLUTH reports with a play-by-play of an all-star love affair

February 1991 Jesse KornbluthAfter a decade of his own fame being eclipsed by Farrah Fawcett's ever rising star, Ryan O'Neal has talked her into bringing him back, on equal terms, with their new comedy series, Good Sports. JESSE KORNBLUTH reports with a play-by-play of an all-star love affair

February 1991 Jesse Kornbluth'I've had the Barbras and the Biancas and the Melanies, and you're ten times what those women were." Ryan O'Neal was supposed to say that to Farrah Fawcett in an early episode of their new television series. It's a golden throwaway—in his days as a Hollywood heartbreaker, O'Neal was involved with many celebrated and beautiful women, including Streisand and Jagger. Then the actor whose prostate once seemed destined for the Smithsonian met the woman whom Lee Majors, her husband at the time, called "every man's fantasy mistress." And everything changed.

There is one constant in Ryan O'Neal's up-and-down life, and that's a sense of humor based on self-deprecation. Good Sports couldn't have existed if he were self-protective—the character he plays is a former professional football star who married a stripper, wrecked his career, and is delivering pizzas when a cable network hands him a second chance, as a sportscaster. This character is loosely based on former baseball star Bo Belinsky, who pitched a no-hitter, hung on for eight more seasons in the major leagues, was briefly engaged to Mamie Van Doren, and then was never heard from again. O'Neal relishes the comparison. "I reach back through all my experience," he says, "and then I become myself—Bo O'Neal,Ryan O'Belinsky."

Ask him about himself and he's even harsher. Is he raising his six-year-old differently from the way he raised his three older children, one of whom he punched out in a highly publicized encounter?

"I haven't knocked his teeth out, if that's what you mean."

Does his daughter Tatum's husband, John McEnroe, remind him of anyone close to home?

"I have no backhand," O'Neal shoots back, "but, sure, a shrill Irish guy."

When you get those answers in the first five minutes, you know there will be bigger fireworks later—and there were, dear reader, there were.

But some things just go too far, even for Ryan O'Neal, and the reference to the Hollywood women troubled him. It used women as punch lines. It had to go. Now. Right at the read-through of the first draft.

Her popularity is huge. So I used her. I said, 'I helped you, now you come along."'

Farrah Fawcett braced herself.

"I sat there thinking: I know him. I know his past, and the stories. I remember a decade ago, when Ryan and I were just starting out and we were in the height of passion; he had convinced me not to wear makeup or worry about my hair—he said I was beautiful without all that. And we ran into Jay Bernstein, my former manager. Ryan said, 'How does she look?' Jay said, 'To tell you the truth, a little tired.' I thought Ryan would jump over the table and strangle him."

Some ten years with Farrah Fawcett and six years as the father of Redmond James have mellowed Ryan O'Neal. Now, as they sat at the script reading, Fawcett didn't worry about violence. She simply waited for him to walk out. When he did, she did, too. For she had a complaint of her own—the script called for her to have an orgasm off-camera. She'd spent her whole career avoiding orgasm scenes. Just because she was playing a former supermodel who once had a weekend affair with O'Neal's character and now, two decades later, finds him co-hosting her sports show didn't mean she wanted her character to bump and grind.

O'Neal didn't call his agent from the Bentley Turbo that Fawcett had given him for his birthday. He waited until they got home. Then he very politely announced that they were withdrawing from the series.

But that hasn't happened. The line about his sexual prowess turned out to have been part of a dream scene that, in his haste, the director simply forgot to label. Her orgasm, the writers claim, was never in the script to begin with. In the end, no one was terribly upset—and this episode, say all concerned, ended up as everyone's favorite.

Still, a certain tension stalks Good Sports, and it's all about the man and common-law wife making their comedic debut together. Two months before the January premiere, the tabloids were already beating the drums—FARRAH BANS FAT RYAN FROM HER BED UNTIL HE SHEDS 25 POUNDS FOR THEIR NEW TV SERIES, headlined the National Enquirer. Elsewhere, there were rumors of spats on the set and friction between the costars.

This publicity is unavoidable. The television season is half over, and it's been notable not for hits but mostly for shrinking revenues, vanishing viewers, and published revelations about the sex life of the late Bill Paley. Now, on Paley's old network, comes a show designed to capitalize on the public perception of Hollywood's most enduringly titillating couple. The show's trick is that, even as it demythologizes O'Neal and humanizes Fawcett, it keeps them in the news. And as Farrah-and-Ryan, they're such icons that they don't have to open their mouths to be quoted.

With all the sideshow going on, it's easy to see why Fawcett and O'Neal might be touchy. This is clearly a career saver for O'Neal, a comic actor with Warren Beatty's charm and an Irishman's love of language, a leading man who once seemed nicely positioned to take over from Cary Grant. And it's a nervous-making return to weekly television for Fawcett, who survived a poster and a jiggle show, saw her career die after a series of flop films, and then gamely reinvented herself with highly emotional roles in TV movies.

This series is a comeback in another, more subtle way. Her hilltop estate in Bel-Air is elegant and inviting, with more of her own sculptures than Warhol portraits of her, every aspect of Hollywood banished to an inner hallway, a racquetball court, and a vast bar overlooking Los Angeles—it's ideal for people who like to entertain. But ever since the birth of their son, Fawcett and O'Neal have been hiding out. She's periodically gone off to work; mostly, though, they've been hermits. So almost the first thing you sense when you step inside is that you'd find very few names in the guest book.

Yes, he's bigger. He's also slicked his hair back and added a small gold earring. But what was most noticeable about Ryan O'Neal as he played racquetball with Farrah Fawcett on a Sunday afternoon was that he took nothing off his shots. He slammed the ball, it took a vicious bounce, she raced to return it. Then she slammed, and he was the one leaping to get to the ball. "Sure!" he yelled as it slipped past him. "Save it for the writer!"

"Tatum made me choose. I said, 'I sleep with this girl, Tatum, I don't sleep with you.'"

They came off the court, glistening and flushed and looking very much like the characters they play in their series—witty jocks jostling each other for ratings. Fawcett went to change. O'Neal had center stage alone. Clearly, this wasn't distasteful; a famous talker, he's had an ever diminishing audience these past ten years. So it took only one question for him to be off and running, dispensing brutal truths with a soft-spoken twist.

"My career was dead as a doornail," he began. "I mean, if I was accepting Norman Mailer's movies, I wasn't getting much—and I don't blame them. I didn't have an audience." How does the star of Love Story and What's Up, Doc? and Paper Moon lose an audience in just a few years? "The turnaround was Barry Lyndon. Now people say it's my best work. But I never got a good job after it. I didn't have an image."

Some suggest there were other reasons. "One thing that hurt Ryan's career was Farrah," says Sue Mengers, their former agent. "If he had fallen in love with Jane Fonda and she had fallen in love with Jack Nicholson, it wouldn't have hurt them. But they're both very Hollywood. Instead of elevating each other's reputation, they negated one another—they were too perfect—they'd walk into the room like two beautiful Barbie dolls and they'd take your breath away."

Reality soon shattered that perfection. One night in 1983 when Fawcett was out of town and O'Neal and his eighteen-year-old son, Griffin, were alone in the house, the boy announced he was leaving. He did not see the fact that he was stoned nearly insensible as a barrier. O'Neal did—and in the confrontation that followed he punched his son's front teeth out. "I was crazed, I was shit, I hated my mother and father, I was about to jump into a two-hundred-horsepower Mini-Cooper," Griffin now says. "My actions that night... if Dad hadn't stopped me, I wouldn't have lived."

Hollywood saw that scene through the prism of O'Neal's reputation as a hothead and brawler. He was, photographers knew, apt to throw bottles at them. Friends were careful with him; he might overturn the table when something set him off. "He could be a nasty piece of work when he wanted to be," one told me. So the town's judgment was as harsh as it was uninformed: Here was a man who could have been a professional boxer picking on a child.

After that punch-out with his son, O'Neal still made $1 million a picture, but he was a ghost. "I knew I wasn't good. I was ordinary. I developed up to a point, and then... I stopped trying, I nearly gave up. I'd made a lot of money in the early 1970s and I'd put it all into old-age trailer parks, so I had about $20 million of real estate—I didn't need to work. And I stuck with Farrah. She had a couple of projects that needed my involvement, just to comfort her. I was there to rub her feet."

O'Neal's gloom was palpable; on an otherwise sunny day, clouds swirled around his chair. The memories got darker: a bitingly accurate role in Irreconcilable Differences that got ignored, a wry performance in Chances Are that also led nowhere. Perhaps audiences began to suspect that there was more to O'Neal than lighthearted gibes and deft comic timing. "When I boxed with him, he hit hard, but he wasn't that hard to hit," Norman Mailer recalls. "In boxing, I saw a dark side of him that was perfect for the role in Tough Guys Don't Dance. I once saw him knock out a guy he didn't like in front of his girlfriend—he could be cruel."

Eventually, the offers evaporated. In the late 1980s, when Bemie Brillstein was at Lorimar, he pushed O'Neal for a film. "I was the chairman of the company, but the director wouldn't take him," Brillstein recalls. O'Neal sent him a four-page thank-you note for trying.

Listening to his tale of woe, I wondered what it might be like to hear actors audition to play Norman Maine, the doomed husband in A Star Is Born. But at that reference, O'Neal brightened. "Is there a script? We can even use my house at the beach! I can't swim, I'll step right in! Sure, I used to call myself Norman every once in a while, but Farrah never let me feel that way, even in her angriest moments. And I worked out, I trained, I kept myself ready—maybe there'd be a series. No, I never thought of that."

Bernie Brillstein did. At a party given by Suzanne de Passe, he spent the evening talking with Fawcett and O'Neal about change. He'd just left Lorimar, and the subject had special resonance for him; he thought O'Neal was due for a change as well. Last year, Brillstein approached him with an idea about the host of a show like Tonight and his wife. "What about Farrah?" O'Neal asked. "Would she be O.K.? Because Farrah and I have a very intense relationship, and she might not want to see me 'married' to someone else."

The focus of the show changed, and suddenly everyone wanted to be in business with Ryan O'Neal again. As O'Neal recalled the last year, the clouds disappeared; I now saw the canny careerist of old. "Farrah's my secret weapon," he explained. "I don't want to do a television series and have it sink. But the chances of it sinking with both of us? Her popularity is huge. So I used her. I said, 'I helped you, now you come along.' She said, T don't do comedy like this—I don't want to play a sportscaster. ' I said, 'That's just what she does, she's a woman in a man's world.' I could have been jeopardizing our relationship—I insisted that she do it. I said, 'I helped you.' "

By rubbing her feet? "For three or four hours at a time." A great many men, I said, wouldn't call that the hardest work you'll ever do. "Well, I did little else," O'Neal shot back. "I fathered the boy, I cued her, I drove her nuts. And now, although she still threatens to walk from time to time, she's grown into it. She sees it as a challenge."

Farrah Fawcett had already had the pilot script for Good Sports for four months when she called Alan Zweibel, the show's creator, to her house. Zweibel is a veteran of the early days of Saturday Night Live, he co-created and produced It's Garry Shandling's Show, he has three children—he came prepared for anything. But when he arrived, he sensed so much uneasiness that he finally had to ask why he was there. "Tell him," O'Neal said. Fawcett blushed. "I just wanted to know," she said after a pause, "what my character majored in in college."

This question sounds frivolous only to the uninitiated. The thing is, for all her beauty, Farrah Fawcett has always wanted to be known as bright and artistic. "I was very shy," she says of her childhood in Corpus Christi, Texas. "I felt different, and I don't know why." One thing she knew: "I wasn't going to end up getting married and staying in Texas."

She was a freshman at the University of Texas, innocently studying to be a sculptor, when she was voted one of the ten most beautiful women on the Austin campus. A Hollywood publicist saw her picture, called her, and spun tales about her future in commercials and movies. She laughed him off, but at the end of her junior year, when she was facing a summer with nothing to do, she had her parents drive her to Los Angeles. The first week, the publicist introduced her to agents; the second week, Screen Gems put her under contract. She was making $1,000 a week. "Don't come home," her father advised.

Lee Majors, a Kentuckian who was strong and male in a familiar way, met her soon after she arrived in Los Angeles. He coached her as she racked up one commercial endorsement after another and had bit parts in a couple of films and small roles in television series. After five years, the Six Million Dollar Man bestowed the greatest credit of all—he made her Farrah Fawcett-Majors. Then he did something even better: he signed up with Jay Bernstein and demanded that, for his $1,000 a month, the publicist represent his wife for free. "Farrah didn't care," Bernstein recalls. "She came in as a courtesy to him. Her interests were racquetball and jogging—she had pretty much given up on a career."

The poster changed all that. For her, it was no big deal. "I was doing a commercial, and the photographer wanted to do a poster," Fawcett says. "O.K., I'm in a bathing suit. It wasn't a bikini—nothing was showing." Though the poster wasn't his idea, Bernstein insists that he knew just what it could do. "The key was nipples," he says. "Those nipples reached every guy going through puberty."

The poster sold 12 million copies and launched an industry that put millions of Farrah items in American homes. At the height of the madness, Bernstein had a dream: "I saw a gas truck pulling up to her house and siphoning water from her faucet. We'd sell tubes of Farrah Fawcett water. It would have been another pet rock."

The pet rock turned out to be Charlie's Angels, a show whose big idea was to have three athletic actresses run around in skimpy attire. It was originally conceived as a vehicle for Kate Jackson, who was paid $10,000 an episode, but the poster queen, earning half that, quickly became the star. The only problem was that she had no contract.

"You pretty much give up whatever life you have when you do a series—especially if you're a woman," Fawcett explains. "You get picked up sometimes at 4:45 in the morning; you can work as late as 10 at night. If you get off early, you have to go to wardrobe. Some days you loop and do publicity—there's a lot. So there were certain things I wanted: a makeup person, a hairdresser, a twelve-hour workday, and 10 percent of the merchandising, which is what I was getting on my own. They were offering 2½ percent. I wasn't about to settle for that. But the show was about to get started, and my attorney said, 'This happens all the time—it will work out.' And it didn't. I remember the tenth show; it was my lunch hour, and here comes their attorney to tell me their best offer was 5½ percent. I said, 'This isn't negotiable. It's so simple—if you don't give me 10 percent, I don't do the show.' "

Maybe she would have settled for less if there had been some interest in elevating the show's artistic content. But the producers, the exceedingly powerful Aaron Spelling and Leonard Goldberg, had a different agenda. "One week, they didn't have a script, so they gave us a Mod Squad script," Fawcett says, still angry after all these years. "They just crossed out the title. It was like: 'You be Line, you be Peggy Lipton.' And I cared. At a very early age, I cared what I said. I knew I had no training, I knew I probably shouldn't speak out, but—excuse me, shouldn't I be saying something else here? So I went into Leonard Goldberg's office and said, 'We've established the show. And I don't know if my character's parents are alive or if she has brothers and sisters—why don't we do a show where all the girls go on vacation and they go back to my house?' He said, 'We have a plan. We have a show. It works.'"

'It's so stupid that we never got married," says Farrah, "The closest we came was Reno. But we ran out of gas."

That seemingly patronizing attitude— the attitude that told her the producers didn't give a damn what her character majored in, or even what sorority she joined—was the final indignity. Fawcett quit the show. She got hired as Chevy Chase's co-star in Foul Play. The producers of Charlie's Angels claimed she was in breach of contract and sued her for $7 million. Paramount dumped her from the movie. Every other studio with a television division that did business with the networks was equally chilly.

But Fawcett didn't budge. "I remember a meeting in my office," Jay Bernstein says. "She looked up at six perspiring attorneys and asked, 'Can I lose my house?' They said no. She said, 'O.K., Jay will handle this. I've got a beauty appointment.' And she walked out."

In her kitchen, she looks so small the inevitable comparison is to a sparrow. But everything about her is smaller than we remember. The mass of hair is pulled back. The toothy grin has a few hundred fewer teeth. She's completely credible when she says that when she wears sweat clothes and no makeup, deliverymen sometimes stare at her, not with lust in their hearts but with the unspoken question: This is Farrah Fawcett?

Ryan O'Neal felt the same way in 1980 when he was in Toronto visiting his daughter, Tatum, on a movie set and he happened to run into Lee Majors. They had been friends in the sixties, then drifted apart. Now, they discovered, they were flying back to Los Angeles on the same day. They flew together. And then, because they were getting on so well, Majors invited O'Neal home for dinner.

"We played racquetball and had dinner, and she burned her hand making cappuccino," O'Neal says. "I thought she was dear. And that was all."

Then Majors suggested dinner the next night. This time, O'Neal got an earful. "They were saying the marriage was over, and I was saying they were terrific together," O'Neal recalls. "She said, 'Lee, remember when we were first married, and we were in Nevada, and you'd leave me in some dinky cabin and go to a bar? You'd tell me to get undressed and get in bed and wait for you, but you never came back.' His answer was 'Same man now as I was then.' He was a very western, Marlboro-type guy. Lots of guns in the house. Moose heads. And as I'm leaving, he says, 'I'm going back to Canada tomorrow. Call Farrah. Take her to dinner.' I said, 'Are you crazy?' Lee said, 'No, I've got Tatum up there.' She was about to be sixteen, so I didn't think anything of it."

O'Neal knew Fawcett liked the music of J. J. Cale, the Oklahoma blues guitarist. He called to invite her to dinner and a Cale concert. "I can't talk now," she said. "I'm about to go to Mass." That response took O'Neal right over the edge. But before the date, Majors called his wife. "I let him know that Ryan asked me out. He said, 'I told him to. But you're t going.' " She said she was. At that, the hang-up calls began at O'Neal's house. He had a good idea who his caller was, so he blurted out, "Lee, don't hang up! Talk to me, man!" The voice on the other end said, "Stay away from my woman!" O'Neal confessed that he was in love. "It was a situation I'd never been in before—committing to a woman before I'd even talked to her about it."

At this delicious moment, Fawcett calls for help in the kitchen. O'Neal goes in. I follow and, as before, need to ask only a single question; this time, however, I get not one but two versions of the recognition scene.

"We didn't have sex for—oh, thirteen, fourteen hours," O'Neal suggests.

"You asked me to marry you," she counters, "before we even kissed."

"You said you finally let me sleep with you because you were up too late every night. To get into bed, you had to take me with you."

"We did some heavy kissing. It was romantic."

While she drops potatoes into hissing oil and he readies the chicken for the grill, I manage to slip in the question everyone asks. Or start to. You bought a ring with seventeen heart-shaped diamonds, I begin.

"We went to Paris," she says brightly. "The paparazzi met us at the airport."

"They pretend they're waiters," O'Neal says, hefting an imaginary tray and starting toward me. "Your dinner, sir. . ." And he pulls an imaginary camera from under his arm and makes clicking noises.

Fawcett's eyes are sparkling. "You said to get comfortable, and you went out."

"I had to use two credit cards for the ring. They take one, then they ask for another, and then you reach for cash and checks."

"It is so stupid that we never got married," she admits. "The closest we came was Reno. But we ran out of gas." Having missed the opportunity, she backpedaled. "In my mind, I'm married," she recalls telling a priest in confession. "You can't make me feel bad. I'm not that kind of guilty Catholic." The priest said he understood—which propelled Fawcett to drag O'Neal in next.

"This means a lot to me," she told him.

"Sorry," O'Neal said.

"I said, 'Ryan, this could ruin the relationship.' "

"You said, 'No sex.' "

"You'd had me do things before that were important to you."

"But they were purely sexual," O'Neal points out. "And I hadn't been in confession in a long time. I'd been married twice—there was too much." He pauses. "Five minutes later, there I was, on my knees. And didn't it bring us a lot closer?"

"Sure did. And we are going to get married, aren't we?"

"You bet," he says cheerfully.

This last bit is a reversal of their usual A byplay, in which he routinely asks her to marry him and she allows as how she likes things just the way they are. This yatta-yatta is, of course, an evasion, and one that has, over the years, sparked endless speculation in Los Angeles about their relationship. Does she refuse him because she feels marriage would mean surrender? Is he so hard to live with that she needs a credible threat—once more and I'm outta here—to keep him in line? Or perhaps the decision not to marry is really mutual. These are actors, after all, who have not worked that much of late; at home, they can generate epic dramas in the belief that a day without crisis is a day without life. Which raises yet another question: if they didn't break up to make up, would they be able to keep themselves interested?

For Fawcett, those questions miss the simple dynamic of their seemingly complicated relationship: "Ryan says black, I say white." There is also a rebellious joy in flouting expectation. The fact is, she says, she might not have married Lee Majors if her parents hadn't been so vehement about it. "I remember being very angry. My parents were upset when I moved in with Lee. And they sort of forced me into this marriage—they made me feel so badly about myself. I remember exactly saying to my mother, 'How do you know?' She said, 'You just know.' And so I thought, Well, I guess I know. But I had a lot of reservations. I got married for all the wrong reasons."

The irony of it is that none of those reasons has anything to do with this relationship. "In the old days, there wasn't one woman in Ryan's life—there were hundreds," says Sue Mengers. "He was like catnip. Women left their husbands for him. And after a while he'd lose interest. He broke a lot of women's hearts and made a lot of enemies of their men. But from the day he met Farrah, there's never been one rumor."

With good reason—they're together almost all the time. O'Neal doesn't like a staff around. Fawcett hasn't been fond of the idea ever since she walked into Redmond's room and his nanny was pulling a toy away and saying, "Mine." As much as possible, they raise their son alone, with all the duties that less privileged parents know well: Sunday-night nail clipping, getting up early to drive their son to school, struggling to work out a schedule with their producers that will allow them to be home for Redmond's nightly bath and story. Even when she's gone away to work, O'Neal's constancy hasn't wavered. "It's not like Ryan adores her when he's with her and then, when her back is turned, he looks at other women," says Alana Stewart, Fawcett's close friend. "They have a connection that's much more special than most people who are married in this town."

That connection has, for all its dramatic downs and manic ups, given them a rare ability to have both a relationship and a business. "Redmond is partly responsible," Fawcett says. "Doing a series is a way for him to be in school and for us to work. I don't feel I can go to Paris now for three months without Ryan and Redmond with me. And it's good for him to see us going to a job at the same time every day. After a film, you have all this coming down." Films are also, she notes, not overly good for relationships. "They're exciting. And then you come back to a relationship, and you have dinner and go to bed—and the home and marriage seem small and unimportant. And that's not fair." Particularly—as she doesn't need to say—when the caretaker was once a movie star.

But the decision to star in a television series does much more than normalize their home life. "Ryan is just one project away from being as big as he ever was," insists Irving Lazar. A series thus represents a realistic way of relaunching him and possibly leveraging them both into bankability—a latter-day Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward. "Television films have helped her, but not in films," notes Sue Mengers. "Physically, she's a leading lady, but by the time she got credibility, she was of an age when it was harder to cast her. By now she knows what her choices are: a TV movie or two a year, a series of her own, a series with Ryan. Any way you looked at it, it was going to be television. The only question was: would she be Jane Seymour or Candice Bergen?"

In that light, the apparent power struggle in their relationship may be a carefully cultivated shadow play that only old-fashioned Hollywood stars could invent. I got a hint of this clinical calculation when O'Neal told me his garbage cans had been closely examined that morning by two well-dressed men who drove up in a Mercedes. I started to bang on about media invasions of privacy. Then I realized he wasn't really all that upset.

Ryan O'Neal is used to a hard time in the press. Farrah Fawcett isn't. And yet ever since they've been together, there have been articles that praise her while questioning her choice in men. Washington Post television critic Tom Shales, for example, recently concluded a tone poem about Fawcett in Esquire with a description of O'Neal as the "lug's lug, the thug's thug, the all-around slug on the sidewalk of life." Hurtful stuff, I noted, and not of recent origin, either—they were calling O'Neal a lout long before she met him. Had she known what she was getting into? What did she know about this controversial man before she met him?

"Take your time," he said.

"I knew he was a great actor," she said carefully. "I thought he was a ladies' man. But when I met him, I forgot all that. He was so charming, so interested, so encouraging—he wanted to know what I had to say. ' '

Did she ever have an agonizing reappraisal?

"Never."

"And I had to make a choice between Tatum and this girl—and I chose Farrah," O'Neal said, his voice rising. "Tatum made me choose. I said, 'That's a bad idea. I sleep with this girl, Tatum. I don't sleep with you.' "

What did Fawcett know about this?

"Ryan's not one to hold back," she said tartly.

"I told Tatum, 'Your problem is that you don't want to see your father happy. And I think that's sick.' "

I suggested that this seemed an ideal beginning for some intensive family therapy.

"She's in therapy, not us," O'Neal snapped. "She needs therapy. She gave up her career."

Stepping into the role of family therapist, 1 announced that I was going to defend Tatum for two minutes.

"I defended her for years," Fawcett said quietly, all but ignored as she fried the potatoes.

O'Neal and I were now toe-to-toe, but I was holding the tape recorder, a far more effective deterrent than wire-rims. Thus emboldened, I pointed out that Tatum started her career—at his urging—when she was too young to know what it meant. Because she moved in with him when she was seven and he took her everywhere for years, it shouldn't have surprised him that she didn't know from minute to minute if she was his date or his daughter. And as for the Oscar she won for her performance with him in Paper Moon—a role arranged for her—that was, on a certain level, not hers to savor.

"She lived with her mother," O'Neal hissed. "I picked her up and I made her a movie star and an Academy Award winner and rich"—here all the air went out of him and his voice dropped almost to a whisper—"and 1 loved her, too. And I never violated her or any of the possibilities. I took care of her. And then I finally met someone who was dear to me, and she couldn't have it, she couldn't deal with it."

There was a pause, and then Fawcett told me how she and O'Neal had asked Tatum to live with them. Instead, she moved in with her mother, the former actress Joanna Moore, whose relationship with O'Neal and Fawcett was more than icy.

The curious thing, Fawcett says, was that Tatum lived with her very happily when O'Neal was off working. In fact, Tatum had her first date with John McEnroe in this house. But as soon as O'Neal returned, so did the friction. Predictably, Tatum went off and married McEnroe, whose reputation for volatility mirrors her father's.

This conversation—which touched so many emotional bases it was at once exhilarating and passionate, depressing and exhausting—seemed to be normal fare around here, for O'Neal and Fawcett went on cooking. Periodically, there would be an outburst from O'Neal and a soft response that wasn't really an accommodation from Fawcett. They helped each other serve dinner. He poured himself a big glass of water. Fawcett bowed her head. Then she recited, for a full minute, a most heartfelt grace.

But it wasn't until I was on the plane home that I found the most revealing testimony to the vulnerability and volubility that power this household. It was a note that O'Neal had scribbled in my notebook. "Be kind!" it said. Underneath it, he'd written his initials. Then he'd written hers. And then, for good measure, he'd written his again.

She fought her television producers, and although it took her years to get back into the business, she says she'd do it again in a minute. She fought Lee Majors when he tried to keep the house she had redesigned and decorated and sunk a fortune into; she won that round as well. She fought her agent and her lover when they told her she shouldn't do Extremities in New York—O'Neal asked, "Why do you want to get beat up every night? You can get that at home, with no critics"— and that image-shattering play led directly to the same part in the movie and the beginning of a new career as a serious actress. In a time when it's uncool to do fur ads, she's done one. On a cable network, over Thanksgiving weekend, she pushed a line of zirconium jewelry she's designed, taking home a nice chunk of the reported $4 million in sales generated by those appearances. Sparrowlike bone structure to the contrary, this is a woman with considerable backbone.

But I didn't really understand how tough she is until she told me the story of The Cannonball Run. She was, she said, then represented by the late Stan Kamen, who headed the film division at the William Morris Agency. Not only did Kamen want her to appear in this Burt Reynolds film, he wanted her to take $250,000 for the role. She was less enthusiastic. The film was to be directed by stuntman Hal Needham. The script, she recalled, gave her lines on the order of " 'You know what I like best about trees? That you can sit under them at night and just fuck your brains out'—or something like that."

This did not seem to her like an opportunity to expand her talent. The only reason to do it, therefore, was more money—say, maybe, $500,000 more. Kamen thought that was impossible. Fawcett met with the producers. Whatever she told them worked; they hired her for $650,000.

"You negotiated $250,000," Fawcett told Kamen. "I got the rest. I'm not going to pay you commission on it."

"You have to pay full commission," he said.

"O.K.," she said, "but then I'll have to leave you."

And she did.

Such self-assertiveness is an echo of someone else in this house. In fact, it's a very short leap from this story to O'Neal's account of the time he and his son Griffin, then twelve, almost starred in Franco Zeffirelli's remake of The Champ. O'Neal had the part; for months he had helped his son prepare for his audition. "The scene required Dad to slap the boy," Griffin told me. "Dad walloped me so hard he almost spun me around. I started crying— as I was supposed to." His father thought it was "a beautiful test." Zeffirelli waited almost to the first day of shooting to decide that a younger boy should be cast.

Ryan O'Neal went to the phone to call Sue Mengers. He still had his boxing gloves on. That made dialing awkward. So he smashed the phone, announced he was quitting, and left. Or so everyone thought; actually, one piece of business remained. He had given Zeffirelli a gold jockey to wear around his neck. Now he wanted it back. With Griffin alongside him, he drove to the director's office. "Wait here," he said. "I'm going to kick some butt." Griffin said it was all right, there'd be another movie. And, at last, they went home (allowing Jon Voight to be quite good in the starring role).

"I admire that about Ryan," Fawcett told me. "His commitment to family or a project—he will walk."

He will also stand, which appeals to the Texan in her. "He taught us to defend ourselves and trust no one, which are O'Neal lessons and lessons of Hollywood," Griffin says. After a hard decade that saw him in rehabilitation for drugs and jailed briefly (for failing to complete the community-service sentence he got after the boating accident that killed Francis Coppola's son), Griffin has moved into an apartment building that also houses his brother Patrick and his uncle, Kevin. Patrick comes to the taping of the show every week; Griffin is equally supportive of the collaborative turn the relationship has taken. "Farrah's been a help to Dad, and that's a help in everything—I can't stress that enough," he says. "I've hated him when he wasn't working. I love him now."

The only one who stands outside the family circle is Tatum, who declined to be interviewed. That's understandable, says Sue Mengers. "This is a very complicated family," she tells me. "In some ways these O'Neals are more the Eugene O'Neills." Though Tatum's father is clearly wounded by her distance, he also defends her; "I miss her. She has a new life, a happy life, with her man." Her half-brother Patrick seems to have the clearest perspective. "I used to have Farrah's poster on my wall—I was thrilled she came into our lives," he says. "I love my brother and sister tremendously. It's too bad Tatum has a problem. For me, Farrah's been like a second mother."

These are, by almost any measure, stable days. "If Ryan hasn't decked anyone yet," Bemie Brillstein crows, "he isn't going to." And this makes for a certain jauntiness. Brillstein, his partner, Brad Grey, Alan Zweibel, O'Neal, and Fawcett are all equity players. No studio developed the series or produced it; no studio gets to charge outrageous overhead. Three years' worth of shows and all concerned will be sitting on a gold mine. Small wonder that, after each taping, Fawcett and O'Neal serve champagne to their partners in their dressing room and review the news of the week.

But, for all its apparent predictability, Good Sports has been crafted by its creators to make sure that O'Neal and Fawcett's professional relationship can survive any private rockiness. "The characters work together, get together, marry, separate, and still have to work together," Brillstein says, "and every word of that is 'maybe.' "

Why the uncertainty? Part of it is the happy result of a creative team that has enormous clout. But another part of it is a calculated assessment of O'Neal's demons, which may not be too far from the surface. He thinks they're mostly chimeras now. But he'll also admit, almost in the same breath, that he's recently told photographers—as a joke—to move aside or he'll start hitting them. They responded by clicking away as he raised his fists. "After all these years," he says, "I haven't ever gotten it right."

No doubt. And it won't get easier when the show is launched and they're ruthlessly examined by gossipists and critics alike. There's the possibility that, soon enough, at some event, he'll get wound a little tight and end up on the wrong end of a juicy lawsuit. For another couple, that publicity—and Lord knows what might follow it—could be crushing, humiliating, humbling. For Farrah Fawcett and Ryan O'Neal, it's simply proof that they're back.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now