Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSLAY 'EM AGAIN,SAM

Mixed Media

Blood, sweat, and coke blur the lines between pleasure and pain in a new biography of director Sam Peckinpah

JAMES WOLCOTT

Sam Peckinpah was a walking WANTED poster. He played the part of an hombre to the gills. With his headband, faded denims, dog tags, mir rored sunglasses, and proph et's beard, he resembled a shaman spawned in the dry cracks of the desert. (His nickname was Iguana.) When he entered a room, everything shifted to one side. But Peckinpah's sudden impact couldn't be chalked up solely to wardrobe. The director of The Wild Bunch, Straw Dogs, and The Killer Elite seemed to have a hand grenade for a heart. You never knew what might set him off. One minute he'd be as mellow as a Willie Nelson song, then—boom— there'd be pieces of meat flying through the air. He didn't play favorites. He fired his own daughter from The Getaway.

Like many despots, he learned to duck. Steve McQueen tried to brain him with a bottle of champagne. Charlton Heston attempted to shish-kebab him with a saber. Yet he also inspired a chain link of loyalty that protected him like love beads. If Peckinpah were ever lost at sea in a crowded lifeboat (it was said), he'd be the last one left alive. As he aged he acquired the hide of a man who had peeled himself off many a dead heap. But his movies remained passionate. He knew how to cater a blowout. Everything flooded and sky-high about Sam Peckinpah emerges in Marshall Fine's Bloody Sam (Donald I. Fine, Inc.), a suitable stocking stuffer for the crazed loners on your Christmas list.

Like Gamer Simmons's earlier Peckinpah, Bloody Sam skimps as criticism of Peckinpah's bullet-ridden corpus. Its punch comes from being an oral history of the old buzzard. A product of Fresno, California, Peckinpah was the grandson of a rancher and the son of a judge. Early in life he learned how to simulate a fall. "My father was a gentle man, but he tended to be violent when he was disciplining us kids," Peckinpah's brother, Denny, recalls. "[He] would backhand Sam and Sam would be flying backward before he even hit him. He'd go flying into a wall and hit the floor." It's almost a flash-forward to the reverse dives his film victims would do.

Canned from a TV station for showing a car salesman scratching his balls, Peckinpah enlisted as side arm to the director Don Siegel, doing a bit part as one of the pods in Siegel's cult classic, Invasion of the Body Snatchers. It was Peckinpah's crisp work on TV Westerns such as The Rifleman that led to Ride the High Country. A stately trot up the trail of John Ford and Anthony Mann, Ride the High Country honored its elders. The gunmen played by Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott had the courtly bearing and raised chins of commemorative stamps. Aside from Junior Bonner (which nobody saw), it's the one Peckinpah film nonPeckinpah fans can stomach.

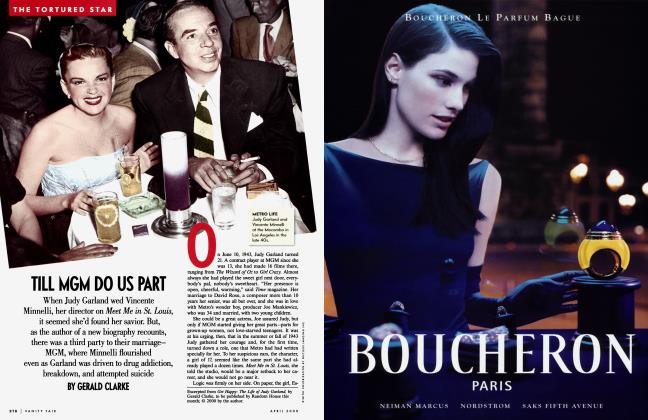

His manic reputation as "Bloody Sam" began with Major Dundee, a cavalry epic climaxing in a massacre worthy of the Charge of the Light Brigade. Way too long, the movie required deep surgery in the editing room. After a preview of the studio cut, Peckinpah stood shaking on the street. His baby had been chopped to bits. "It's just a movie," he was consoled. "It's my fucking life," he said.

He later took a harder hit. Hired to direct The Cincinnati Kid, he spent three days shooting a scene written by Terry Southern involving Rip Tom, a caramelcolored hooker, and a sex utensil. The producer freaked. After a snap huddle of the studio brass, Peckinpah was replaced as quarterback. It's rare for a director to be fired from a film in progress. He was now tarred in Hollywood as non compos mentis. It would be three years before he could unleash his furies.

Shot in bunghole Mexico ("hot, isolated, primitive, with daily sandstorms and the occasional monsoon"), The Wild Bunch was a bitch to realize, a daily horror of skittish horses, ammo problems, foolhardy stunts, and slave-ship morale. More than a third of the crew was fired by Peckinpah, who was puking at both ends. But the result was the most prodigious payload by an American director since Citizen Kane. Blood spits from a caldron across a catalogue of knitted details—the white of William Holden's shirt, the hang of Robert Ryan's head—as history seems to draw a dusty blanket over this godforsaken ant farm. The slow motion, much copied, has never been topped as a lyrical shredder except by Peckinpah himself. Some shockers back when become tame in time. Not The Wild Bunch. It still has all its thorns.

After a harmonica toot titled The Ballad of Cable Hogue (an itchy idyll featuring Jason Robards hopping around in long johns), Peckinpah returned to the pit with Straw Dogs, in which a country house in Cornwall plays host to rape and pillage. A thesis film (pacifism is for pencil-necks), Straw Dogs has the snarl of a cornered animal, its siege finale escalating into a cruel trance.

It was during this onslaught that he solidified his image as a boozing, whoring, woman-beating, sucker-punching, knife-tossing, paranoia-crazed, tear-ass taskmaster. Peckinpah drank himself horizontal, traumatized Susan George, did the dueling-memos bit with the producer. "By the time of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, playing the part of Sam Peckinpah was practically a full-time job.''

It took its toll. He was a limp rag shooting Pat Garrett, a pulpy prose poem which has James Cobum and Kris Kristofferson exchanging heavy nods while Bob Dylan fidgets as if he needs to pee. Reviled at the time, Pat Garrett has acquired the patina of a flawed masterpiece. Received opinion is that the movie was crucified by Crass Commercialism at the evil behest of MGM boss Jim Aubrey, a model for Jacqueline Susann's Love Machine. Fed up with Peckinpah's tactics, Aubrey ordered his own cut of the film. Peckinpah plotted revenge. Get on a plane to Mexico City, he told photographer John Bryson. "Get a couple of pistoleros. I'll fly them up here first class and they'll kill Jim Aubrey."

Aghast, Bryson refused: "I can't do that, Sam," he said. "That makes me an accessory if they kill the head of MGM."

Peckinpah gave him a cold stare and said, "I thought you were a friend of mine."

But as Bloody Sam makes evident, Peckinpah wasn't averse to taking a hike from his own edit. Perhaps he knew no amount of hunkering at the console could supply its missing vital organs. Even in die restored version that played a New York art house to rave reviews, Pat Garrett remains a ghost sonata packed in gore.

A better case for critical revise can be made for the appalling Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia. As funky as a disco funeral, Alfredo Garcia has flies buzzing on the sound track, hit men in flared pants, Warren Oates mildewing the screen like a problem stain. But the movie has a strange Poe-like stupor from the moment Oates awakens after his premature burial following a blow from a shovel to the climactic, silhouetted sweep of bodyguards pumping shots into his getaway car as he slumps behind the wheel. There's no escape, no redemption. No wonder punks considered him a brotherman. Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia is the most unreconstructed chunk of slow-death nihilism ever committed on and against film. Talk about wasted.

Out of muttering confusion Peckinpah created a chaos of which he was king. He hurled everything he had into the breach.

Peckinpah became permanently wasted when he switched from alcohol to cocaine in the seventies. Or so I found when I tried to cover the caravan to nowhere that was Convoy in 1977. The temperature in New Mexico was in the triple digits. The movie was overbudget and behind schedule. Trucks sat idle. Stars sulked in their trailers. One afternoon I was summoned to one of the trucks for a Private Audience. Without preamble, he began whispering a story about an old whore's first love. Upon reaching the punch line, he let fall a silence that made clear no more needed be said. He left the cabin as if he were a John Ford hero bidding adieu to the old homestead. Years later I found the story verbatim in a book about Peckinpah. He told everyone that can of com.

There were times when he was more amenable. He would let his bandanna droop over his eyes, and stagger to actress Madge Sinclair, fumbling for her breasts and moaning, "I'm blind, I'm blind." But another afternoon I managed to get caught in his aerial. I was behaving myself when Peckinpah spun and accused me of being a ball-less wonder content to watch as he put his cock on the line. ' 'The truth is what you do," he snapped. "All the rest is illusion." He then stomped off like Achilles to his tent.

To the crew his tantrums had become ho-hum. They were plotting to get him boozing again. As one explained, "Sam's a mean son of a bitch when he drinks, but at least he's in broadcast range. When he's on coke, he's unreachable." How unreachable Bloody Sam makes clear. He refused to come out of his trailer to shoot a scene involving three thousand extras and a hundred trucks. His whims continued through the editing process. "His cut had a scene of Ali MacGraw running across the screen upside down," recalls a producer with an ice pack on his head. The best thing about Convoy is the opening shot of white dunes, which evoke virgin mounds of cocaine.

Peckinpah was shunned after Convoy. He did little but diddle until The Osterman Weekend, based on one of Robert Ludlum's wordy blobs. Along with a phenomenal sequence involving bodies plunging into a burning swimming pool, The Osternum Weekend boasts an opening unlike anything Peckinpah had ever done, a masturbation scene in which Marete Van Kamp, dazed, glazed, frosted, is murdered by intruders—on video. It's almost a mini-essay on the mystique of the snuff film, with a suspended pang of violation.

It is either a boon or loss to the culture that Peckinpah never photographed sex dead-on, because the evidence of Straw Dogs and the Osterman intro is that he could have become Andrea Dworkin's worst nightmare, a demon pomographer burning a cigarette hole between hate and lust. He could have whipped a team of male/female whores roughshod into hell. He had the artistry, the Dionysian drive, to thrash all our moral-social-aesthetic criteria regarding the proper doses of pain and pleasure.

He thrived on tumult. Following a heart attack, he had six lawyers hovering around his bed. He became convinced that his pacemaker was a C.I.A. plant that could be detonated at any time. His system finally caved shortly before his sixtieth birthday. At his memorial service in 1985, an actor informed the crowd, "You can tell this is a Peckinpah production. We got started late and nobody knows what's happening." It's amazing what he was able to make of such milling around in his prime. Out of muttering confusion he created a chaos of which he was king. He hurled everything he had into the breach. The unresolved feelings of the speakers in Bloody Sam suggest that the debris from his campaigns is still falling. Personally, I found him a heroic presence, even if he did call me a pussy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now