Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

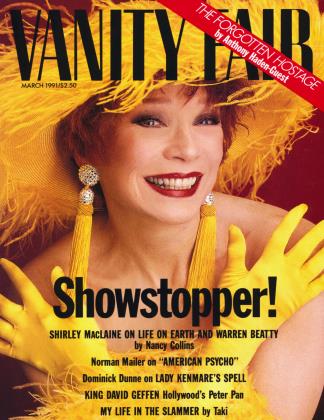

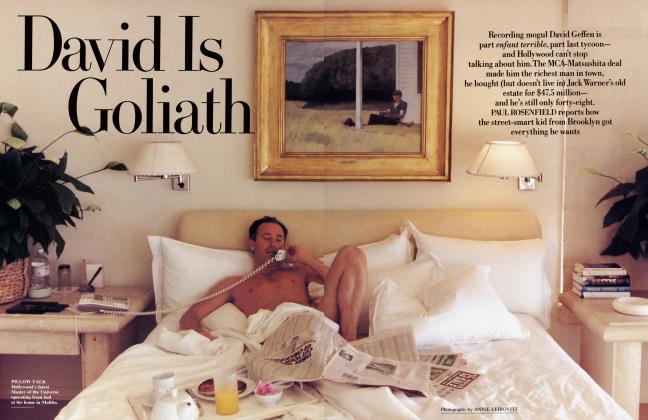

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTERRY WAITE'S ENDGAME

Did Terry Waite, the Anglican envoy kidnapped four years ago by the radical Shiite Hezbollah sect, become a pawn in the Iran-contra power play? And how might the shifting alliances in the Middle East affect Waite and the other hostages held in Lebanon? ANTHONY HADEN-GUEST reports from Beirut

It was eerie watching a sort of peace settle over Beirut. The fighting was elsewhere in Lebanon. Here, even at night, the guns w^re quiet. This was early November, and Lebanon's president, backed by a Syrian army 35,000 strong, had given the warring mia deadline to leave the city. You would see small convoys on the roads as angry or apathetic fighters trundled their tanks, field guns, and truckfuls of rockets out of a city in which barely a building was unscarred to their fiefdoms in the countryside. Even Hezbollah's soldiers were on the move.

Hezbollah, "the Party of God," is the sect of pro-Iranian Shiite Muslims that was holding most of the Western hostages. I had returned to Lebanon because of a surge of reports that certain hostages would soon be released. The reports came from sources—Arab and Iranian newspapers, for instance—that had often been correct in the past. Much of the speculation had centered on one particular figure: the archbishop of Canterbury's envoy, Terry Waite.

Waite had originally hoped to be the solution to the hostage problem. He had first come to Beirut in 1985, paid a sequence of visits, and been credited with the freeing of three Americans. Then Iran-contra exploded, smearing Waite. Two months later, during a face-saving hostage-negotiating mission, he himself entered the huge country of the disappeared. Since that day, January 20, 1987, rumors—never a scarce item in Beirut—have proliferated. A bizarre early report had Waite walking the streets of Beirut's southern suburbs— Hezbollah-controlled territory—waving at passersby. Later tales had him dead; operated on after an accident; taken, alive, in a coffin to Teheran. A recent and more substantial account had him in frail health, possibly from being confined in a small room alongside a generator, and in understandably low spirits.

But nobody, as yet, knew for sure. As the militias withdrew from Beirut, I took a wary look at some of the places where hostages had almost certainly been held, most notably, the Haymadi Barracks, a.k.a. the Hostage Hilton. Small green Iranian flags fluttered around Haymadi, a gaunt two-story concrete carapace, with only heaped sandbags keeping out the weather. The narrow entrance was protected by an L-shaped wall. A Lebanese fighter opposed to Hezbollah who was interrogated there reports that there are three underground levels below Haymadi, and that foreigners had been held on the lowest. Men wearing the trim black beards of Hezbollah were moving restlessly to and fro. Neither Syrian troops nor government soldiers were yet venturing into the teeming streets around Haymadi.

The Mouallem Barracks is nearby on what locals call "the Old Damascus Road," an area that fifteen years of sporadic gunnery have given the look of fossilized honeycomb. While Hezbollah members had still been flitting around Haymadi, at Mouallem the only vital signs were more flapping flags. Gossip had this as a likely recent hostage venue because instead of leaving the barracks by the Syrian-enforced noon deadline, Hezbollah had left at night. Among the vehicles departing, it was said, had been several Mercedeses and Range Rovers with windows curtained against prying eyes, the kind of cars often referred to as "Hezbollah limousines."

The convoy had almost certainly gone to the Bekaa Valley, the seat of Hezbollah power, about thirty miles from Beirut. Where the game being played with the Western hostages was concerned, the playing field had now shrunk. But, like the croquet game in Alice in Wonderland, it's a game of fluid rules.

The spate of rumors concerning releases that had brought me here had some logic to them. "There are two keys to the hostage question," a Lebanese journalist had told me. "A Syrian key and an Iranian key. And both must turn at the same time." Well, Western relations were warming with both Syria and Iran. Realpolitik and the convulsions wrought by Saddam Hussein were making America treat Syria, until recently shunned for sponsoring terrorists, as its New Best Friend. It was with the State Department's tacit support that Syria now occupied almost three-quarters of Lebanon and was bringing an end, at least temporarily, to the fifteen years of Lebanon's civil war, which had embroiled more than a dozen Muslim and Christian sects, tribes, and political parties, to say nothing of warring Palestinian factions and Iranian Revolutionary Guards. Iran itself, since the ayatollah, had been as deadly a foe to the United States—"the Great Satan"—as Syria. And it was Iran that had been financing Hezbollah. But now the word was that the Iranians were massively cutting back on their support; Iran, too, was hesitantly moving toward better relations with the West. The release of hostages would provide a clear signal, especially the release of the most singular hostage of all, Terry Waite.

Tery Waite was bom in 1939, the son of a village policeman, and grew up in Styal, in the North of England. He was a tower of a youth—over six feet seven—and joined the Grenadier Guards as an enlisted man. A rare allergy to the khaki dye ended his military service, and he went to the Church Army College, London, to study theology. In 1964 he married Frances Watters, the daughter of a Belfast solicitor—they have three daughters and a son—and in 1968 they left for Africa, where Waite was appointed adviser to the first African archbishop of Uganda. Deeply religious, Waite had no desire to be ordained, and was no narrow zealot. In 1972 the Waites left Africa for Rome, where he consulted with the Roman Catholic Church on missionary work in Africa, and then was employed in Vatican City. Dr. Robert Runcie, the new archbishop of Canterbury, brought him back to England as one of a fourman kitchen cabinet. His salary was under £16,000 a year.

Waite's first involvement in hostage politics came in early 1981. He was sent to Iran as the archbishop's "special envoy" and secured the release of three British missionaries who had been held for six months for "spying." In November 1984 he was sent to Libya, where more Britons were being held by Colonel Qaddafi. The friendly, hefty Waite—he was now 250 pounds—paid several visits to Tripoli, and got on good terms with the mercurial colonel,

"At his first meeting with Qaddafi he couldn't fit into the tent," says Brent Sadler, a correspondent with Britain's Independent Television News, who first met Waite in Libya. "He hunched his shoulders and made a joke. He was very good at breaking the ice. He would always come up with something. He was a congenial man. He would always pay attendon to the bellboy, the receptionist."

Waite's initial visit to Libya had been low-key. His later forays were enthusiastically covered by the newspapers and television, much to his glee. ''He liked the whole razzmatazz of media," says Sadler, who photographed the envoy accoutred as a TV cameraman on the Tripoli seafront. Naturally, Waite dominated the press conference at Lambeth Palace, the seat of the archbishop of Canterbury, after Qaddafi freed the Britons.

Waite took to his new prominence with aplomb, and the clerkly sobriety of his attire—an inexpensive dark threepiece suit, dark tie, black brogues (size 11 ½)—emphasized his sheer bulk. ''He was a formidable object," Sadler says. He was also busy acquiring the deftness that his new prominence seemed to require, although sometimes the insecurities poked through. One friend remembers ordering lamb chops with Waite. They came in minuscule, dollhouse-size helpings. ''I could see what he was thinking," she says. ''Which was, How am I going to eat these?"

She picked hers up with her fingers. He quickly followed suit, saying, ''We can do this. We're from the North" (meaning: So much for London airs and graces).

Waite's triumphs had not gone unnoticed by the church in the U.S. Two of the American hostages in Lebanon were churchmen—the Reverend Benjamin Weir, who was taken in May 1984, and Father Lawrence Jenco, who was grabbed in January of the following year. The Episcopal Church in America decided to involve Waite in negotiations for the clergymen's return. The news was conveyed to the capital's most powerful active Episcopalian, the vice president, George Bush. Word came back that the White House wanted to be kept informed on Waite's mission.

Waite first visited Beirut in 1985. Bishop John Allen, who was then head of the Episcopal Church and occupied the same position in America as the archbishop of Canterbury does in Britain, describes Waite as representing ''a church network.... We paid some of his airfare." The mission was fairly secretive; Waite did not arrive wearing a cassock, as he had in Iran. And things went well. On September 14 Benjamin Weir was released from a car on the Beirut seafront—known as the Corniche—and Terry Waite's role became public knowledge.

In early November a letter was written to the archbishop by four of the other Americans in captivity: Thomas Sutherland, the dean of agriculture at the American University of Beirut; Terry Anderson, an A.P. correspondent; David Jacobsen, also of the American University of Beirut; and Lawrence Jenco. They asked for Waite to persevere.

He returned to Beirut the following week. Militiamen still speak of his courage. "He would cross the street when snipers were firing," one told me. "He didn't care." "He would watch the fighting from his window," another said. Waite's talks with Hezbollah apparently bore fruit, and Jenco was duly released. Waite was at his side when the priest had audiences with the pope and the archbishop of Canterbury. There was speculation about Waite getting the Nobel Prize.

On the morning of November 2, David Jacobsen was freed. Larry Speakes, Reagan's press secretary, credited Terry Waite. A breakthrough in the release of Thomas Sutherland and Terry Anderson was expected within twenty-four hours, and Sutherland's wife, Jean, who had been visiting family in Colorado, returned straightaway to Beirut.

"You will not see him anymore," a Hezbollah said. She didn't need to ask who.

Hezbollah came to life subsequent to Israel's invasion of Lebanon in 1982. Its mission was the turning of Lebanon into a radical Islamic state and destruction of Western influences there. Its first strike was the suicide truck bombing of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut in April of 1983. On October 23, suicide trucks hit the barracks of the French paratroops and the U.S. Marines within moments of each other. Two hundred and forty-one Marines and fifty-eight French died.

The United States responded in kind. Reagan authorized the C.I.A. to train counterterrorist squads to attack Hezbollah. One such squad targeted Sheikh Fadlallah, who is commonly referred to as Hezbollah's "spiritual guide." Their instrument, a stupendous car bomb, killed more than eighty of Fadlallah's neighbors from Beirut's southern suburbs, and wounded hundreds, but didn't so much as singe the sheikh's voluminous gray and white whiskers.

I saw writing on the wall beside Sheikh Fadlallah's house in Beirut. The handsome blue Arabic script was translated for me as DEATH TO AMERICA. A red slogan ran, NEVER FORGET. Nearby buildings looked like squashed concertinas, and one had been replaced by a parking lot. A couple of architect's models for sizable mosques sat on a side table in Fadlallah's salon, but otherwise the place was stark. Fadlallah was wearing a dark turban, a cafe au lait jibba, and sat with his fingertips pressed delicately together. His manner was less that of a preacher than that of a formidable professor.

I asked him about the hostages. "I have declared I am against hostagetaking from the beginning," he told me. "It is the policies of the United States and some European countries that created these inhuman actions. But I am working to solve the crisis nonetheless."

He had two solid suggestions. First, Britain should restore the diplomatic relations with Syria which Mrs. Thatcher had severed in 1986 after the involvement of the Syrian Embassy in an attempted bombing at Heathrow Airport. Second, the U.S. and Britain should "act positively in favor of the release of the Iranian hostages held by their allies in Lebanon."

This is crucial; Hezbollah were not the first people to take hostages in Lebanon. The country's civil war began as a fight between one of the Christian militias and the Palestinians who had built "a state within a state" in the country after King Hussein had ousted the refugees from Jordan. The war began in 1975; hostage-taking began shortly thereafter.

Trying to establish who began the kidnappings in Lebanon, I visited the Palestinian camp Mar Elias, which is controlled by hard-liners opposed to Arafat. The spokesman for the Salvation Front, one of the factions, listened to me in silence. "This page is now closed," he told me with an unhappy smile.

A dour, stocky man took my press card in the office of the Abu Nidal group and disappeared. I wanted to talk to Abu Nidal's representative. "He is not here now," he told me on his return. "Come back in two hours."

"They are liars," my guide said outside. "He is there. Where do you think they took your card?" He didn't want me to return. "They like taking hostages, the Abu Nidal people. They can bargain. For money or arms. They still have some Belgians." Where? I asked. "Most probably this camp. Maybe this building. Nobody can know."

Israel's 1982 invasion of Lebanon was intended to smash the P.L.O. During the blitz, the Christian militia called the Lebanese Forces, at the time allies of Israel's, stopped a car at one of its checkpoints. The passengers were three Iranian diplomats. They vanished with their driver. These are the Iranians Fadlallah was referring to.

On July 19, just days after the diplomats' capture, pro-Iranians retaliated, kidnapping a citizen of Israel's most powerful ally. David Dodge, an American, the president of the American University of Beirut, became the first Westerner kidnapped in Lebanon. He was released a year later.

In the beginning, though, Hezbollah was less preoccupied with hostagetaking than with big and bloody actions that would grab world headlines, P.L.O.-fashion: bombings, hijackings, assassinations. Many of these took place abroad. In 1983, for instance, members of a radical Shiite sect, A1 Dawa, which included Hezbollah members, were arrested after plotting bombings in Kuwait. They became known as the A1 Dawa Seventeen.

The kidnappings that Hezbollah was responsible for during this period were few and functional. Frank Reiger, an engineering professor at the American University of Beirut, was taken in February of 1984, just before the trial of the A1 Dawa Seventeen (no coincidence), William Buckley, the C.I.A. station chief in Beirut, was taken March 16. (Buckley is believed to have died after breaking under torture.) Thomas Sutherland was picked up on a drive from the airport, a target of opportunity, on June 9, 1985.

On June 14, Hezbollah hijacked TWA Flight 847 in Athens. The plane squatted on the tarmac of Beirut airport, and its hostage passengers occupied the world's front pages for the next sixteen days. The 847 affair had two important consequences. First, it was not only Syrian but Iranian pressure that prevailed on the hijackers to surrender the plane, causing Washington to realize that it now had to deal with Iran as much as Syria. Second, the Hezbollah hostages already in Lebanon came into sharper focus.

"They tacked them onto the TWA thirty-nine," says Jean Sutherland. "The media started calling the other hostages 'the Forgotten Seven.' And the captors could see that it was big business."

The fact was that Hezbollah's spectacular terrorist actions had gotten gruesome attention, but the attention was always short-lived. A corpse is a corpse. A live body is an asset. Kidnappings suddenly became a serious strategy for Hezbollah, and numbers climbed. Foreigners from targeted nations would be either bargaining chips, useful for striking political deals, or, failing that, commodities with a price tag: $2 million a head.

By the time of the TWA hijacking, Waite was widely extolled for his negotiating skills—a profile in a British Sunday paper was headlined THE CHURCH'S OWN DR. KISSINGER. He and Frances lived in the solid, resolutely ungentrified London suburb of Blackheath. Their friend Brent Sadler lives in Ealing. They had grown close. "We were both northerners living in the South. It was a bond," Sadler says. It was Waite who announced Sadler's engagement to Debby Lockett—another northerner—at a party in Sadler's garden in August 1985. Another guest recalls Waite enjoying himself hugely at the party, very much the center of attention, while Frances sat by herself on a swing. "She was rather a nunlike figure," the partygoer recalls.

Waite's friends were aware that alongside his expertise was a basic ingenuousness. Debby Sadler was driven by Waite to Manchester in the spring of 1986 in his adored two-seater, a fifteenyear-old blue MG with ripped upholstery, and noted his sheer pleasure in being recognized. "We stopped at a petrol station in Birmingham for fortyfive minutes," she says. "I don't know whether it was because people wanted to talk to him or he wanted to talk to them. I had icicles on my nose. He really liked people." This liking for people—the simplicity, even—was his most effective weapon. How would Colonel Qaddafi have responded to a more Kissinger-esque negotiator?

Actually, Waite's ingenuousness was not holding him back as he began to move in a less restricted world than that offered by Lambeth Palace. The Honorable David Astor, former editor of The Observer, put him on the board of the Butler Trust, which rewards excellence within the penal system, "so that the prisoners don't come out all bitter and twisted," the administrator explained. He set up an organization to aid the developing world called Y Care International, with many dignitaries among the trustees. He was introduced to George Bush. "He was dancing amongst fashionable people and he was enjoying it enormously," Brent Sadler says. "He was going places fast—almost too fast."

Then there was the larger dream. Terry Waite was the man who had worked with both the Vatican and the Church of England. He had shown that he could apply the human touch in both Iran and Libya. He had done better than anybody else in Beirut. He was definitely leaving Lambeth Palace, and had ambitious plans for his future. What he had conceived of was a sort of humanitarian Mission Impossible. It would be amply funded, have distinguished backing, and would be available to act whenever and wherever the intense religious passions of our times put human lives at risk. When diplomacy and statecraft failed, Terry Waite would be the Red Adair in the fire storms of belief.

"Waite would cross the street when snipers were firing," one militiaman told me.

Accordingly, he began to turn himself into the sort of figure who could swim in these deeper waters. "He was still insecure," says another friend. "He was always worrying about his appearance. He would ask your opinion on if he was wearing the right shirt." His weight bothered him in particular. He liked good food and wine, and his heft showed it. He went on a diet. His mid-life celebrity made him want to cut a more alluring figure. His fame at once fascinated and alarmed him. He called up one friend to say that he had heard he was to appear on Spitting Image, a TV show featuring grotesque puppets of people in the public eye. He called back the moment the show was over for an opinion. "He wanted me to give him a ten out of ten or a nine out of ten," the friend says. Actually, Waite was depicted on Spitting Image as a bit of a stooge, being thwacked about the head by the archbishop of Canterbury, and Waite was tom, but basically enjoyed the attention.

There's no question but that Waite found Lambeth Palace's reaction to his exploits lukewarm by comparison. There he was still a layman on salary. "He was very impressed when I sent a V. I. P. car to pick him up. Normally he paid for his own tube," a TV correspondent says. "Then the Americans are suddenly offering him helicopters.'''' It was respect.

On November 3, the day after Jean Sutherland returned to Beirut, Al Shiraa, the Beirut weekly, came out. Its cover was headlined THIS IS WHAT HAPPENED IN TEHERAN, and the story within gave details of Reagan's emissary Robert "Bud" McFarlane's trip to Iran that May. The news that the White House had been trading arms for hostages soon became the biggest thing since Watergate. "You get a sinking feeling," Jean Sutherland told me. "Things have gone wrong.. .things have gone wrong..."

There are armed bodyguards in the lobby of Al Shiraa, and five kalashnikovs are propped in a comer like umbrellas, but the office of the editor, Hassan Sabra, has a pre-war chic, with four buttoned sofas in pale-gray leather and enlarged photographs of an unbombed Beirut. A portrait of the late Gamal Abdel Nasser emphasizes the likeness between the two, though the editor shows little of the Egyptian's ebullience—understandably, because Iran-contra affected him too, if not as greatly as it would Terry Waite.

(Continued on page 216)

(Continued from page 152)

Sabra was given the tip about the McFarlane mission by Mahdi al-Hashimi, a friend for eleven years. Hashimi was leaking on behalf of Iranian hard-liners who opposed any rapprochement with the United States. Supporters of the arms-for-hostages caper killed Hashimi after publication. They also went after Sabra.

At ten in the morning on September 14, 1987, the editor was reading the newspaper in his car. His ten-year-old daughter and seven-year-old son were in the car, too. A couple of passing gunmen turned the vehicle into a salad strainer. Amazingly, nobody was killed, although Sabra's son took a bullet in the stomach, his daughter was hit in the leg, and the editor himself was struck in both the neck and the cheek.

Sabra gloomily showed me where the bullets had hit. Who did it? I asked, expecting to hear the C.I.A., Mossad, etc. "Iranians," he said simply.

Two of Sabra's men drove me back to my hotel in an armored black Mercedes 500SEL. One, not liking the looks of a passerby, pressed a knob. The doors locked with the clunk of a meat locker. At the hotel the driver rolled down the window and proudly showed off the glass, layer after layer, as thick as the Iran-contra report, for when Al Shiraa gets its mitts on another stunning scoop.

After Iran-contra broke, a squall of speculation surrounded Waite's relationship with the Iranscammers. He distanced himself at a November press conference in Lambeth Palace. Waite sat with the three hostages whose release he had been credited with and read a somber statement. "My experience over the years has taught me that in the Middle East, at the end of the day, there are no secrets. As a representative of the church, I would have nothing to do with any deal which seemed to me to breach the code to which I subscribe," he said.

"Not only because I know that such actions would undoubtedly come to light one day but, more importantly, they would destroy my independence and credibility."

He added, "I also feel obliged to say that the rumor and speculations of the past week have done immense harm." Archbishop Runcie said they were deciding "how best we might continue our humanitarian efforts in order to seek the release of hostages currently held in Lebanon."

It was true, of course, that Waite had met with Oliver North. He had been introduced to the gung ho colonel in the summer of 1985 by Bishop Allen. There were several meetings in the following two years, some in Bishop Allen's New York apartment, others in London and Cyprus. It was the misinterpretation of these meetings, both by conspiracy-theory journalists and, more tragically, by Hezbollah themselves, that led to Terry Waite's becoming one of the most conspicuous victims of Iran-contra.

In Colonel North's diaries, subpoenaed for his trial, a memorandum of December 5, 1985, to Admiral Poindexter headed "Top Secret" refers formally to "Special Representative of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Terry Waite," which suggests no degree of closeness. Waite was supplying and asking for information, as his mediator role demanded. Doubtless he was dazzled by Washington's attentions. Doubtless, also, he assumed that other initiatives were afoot. Waite, though, clearly thought the hostages were being released through his efforts.

But he was a beard.

Even as the White House continued to broadcast the official line that there would be no deals done with terrorists, the armsfor-hostages trafficking was under way. Terry Waite was the administration's decoy.

The unwitting envoy came close to being put to darker uses: when a bombing of Qaddafi was being planned, Oliver North, according to David Martin and John Walcott, the authors of Best Laid Plans, proposed that Waite be asked to go back to Libya to meet with Qaddafi to ask him to intercede concerning the hostages. Waite was not to be told that this was merely a way of making sure that Qaddafi was on the spot, and that U.S. planes would strike after Waite departed. It didn't happen that way, but it is chillingly suggestive of the way that Washington was willing to exploit the bulky envoy.

Nor does London shine. In early December 1985, subsequent to the freeing of Benjamin Weir after (as we now know) the delivery of 504 TOW missiles to Iran, McFarlane and North met one of the Iranian fixers of the deal in a London hotel room. This meeting was bugged by M.I.5, which is the British equivalent of the F.B.I. For the sorts of reasons spooks have, M.I.6, the British C.I.A. equivalent, made the C.I.A. aware of this.

So London knew that Washington was dealing with the Iranians and trading arms for hostages. And Washington knew that London knew. Terry Waite, who thought he was playing the game, was just one of the pieces on the board. When Iran-contra was exposed, leaving Waite looking like a holy fool, or worse, he decided that the most effective way of restoring his name would be to pick up the pieces of his mission where he had left off—in Beirut.

Waite dined with Brent and Debby Sadler at Langan's, the then modish London brasserie, on a Saturday night in early January 1987. He and Sadler planned to leave for Beirut, via Cyprus, shortly. Waite had grown ever closer to the Sadlers. "He would always pick up the phone, wherever he was," Brent says. "It would normally be at two in the morning. Human contact is what he needed."

"He hates to be alone," says Debby.

They had a window table. Debby remembers that singer Paul Simon was seated nearby. They dined lightly on souffle. Waite was proud of his progress with his diet. "How much more do you have to lose?" she asked.

"Ten pounds," he boasted cheerfully.

But the mood darkened as Waite told them of his hope of meeting some of the hostages, and of the warnings that he had been receiving. Debby Sadler began to weep. "The things he was saying made it seem like a last trip," she explains.

Brent does not agree. "I think he thought he was invulnerable," he says. "He didn't think he could be taken." Sadler and Waite left for Cyprus a few days later, and Sadler took a room in the Golden Bay hotel in Lamaca. He was to remain there until Waite gave him the green light. Waite flew to Beirut on Monday, January 12, and called Sadler the next day. "It was a hissing, barely audible line," remembers Sadler. "Terry said that he wished Debby a very happy birthday. But he said, 'Whatever you do, stay away from Beirut for now. It is too dangerous.' "

The Druze are a small Muslim sect. A mountain tribe, they are feared fighters and had been successful in getting three Soviet hostages released (a fourth had been murdered). They also, at the request of both the British and the Americans, provided the security for Terry Waite. "We met with him at the airport," one of the detail told me. Security had been intense, and only two of the bodyguards knew whom they were meeting. They were startled to find TV and press there, and decided that the media had been alerted by Waite himself. Plans to keep Waite in a "safe house" were then abandoned, and he was checked into the Riviera Hotel on the Comiche, where he could be securely guarded, and where he could brief the press in Dream, the coffee shop on the ground floor.

The following day Waite, looming over his seven or eight bodyguards, who were toting everything from kalashnikovs to an American shotgun, set off for his first meeting with the designated go-between with the kidnappers, Dr. Adnan Mroueh. The round-faced doctor seemed the perfect choice. He had been the minister of health in a previous administration. He was a Shiite, and personal gynecologist to the wives of Hezbollah leader Sheikh Fadlallah and other important Hezbollah. Finally, he lived on the Avenue John F. Kennedy, which is just up the road from the American University Hospital—where he had a practice—and which is an area firmly under Druze control.

Waite spoke with Mroueh in his clinic, which is on the fifth floor, a flight above his apartment. His goal was the freeing of two Americans, Terry Anderson and Thomas Sutherland. He asked to see at least one of them face-to-face. Mroueh was emollient.

"What you have asked is possible. But you must be patient and work with the kidnappers in their own way. You are in Lebanon, not in America or England." (Did Waite note that the U.S. was mentioned first? ) "Remember that well. I will contact you tomorrow evening." It had taken just twenty minutes.

There was an air of forced ceremony about the next few days, with Waite paying well-publicized calls on notables such as Sheikh Fadlallah. "It was almost as if he was starting out all over," Jean Sutherland says. "Every hostage wife has done all of those things. You do it once. To do it all over again, and to do it publicly—it was clear that it was very much a gesture. Doing things the right way."

Sutherland herself visited Waite at the Riviera Hotel, along with the wives of two of the more recent hostages, Frank Reed and Joseph Cicippio. "It was really something, with all of the media," Elham Cicippio told me. "I said, 'You should do something for all of them, not just two.' I was furious. He said, 'Well, I do not know if I can succeed or not. I will try my best.' "

In between times, Waite would read in his room or play classical music on his Walkman. He would take bracing AngloSaxon walks up the Comiche, pausing to drink fresh orange juice at the stand of the wiry fellow nicknamed "Abu Ali Cholera" for his alleged standards of hygiene, now more commonly known as ''Abu Ali Terry." He toured the ruined grand hotels. ''Sometimes he used to like to just sit and look at the sea," says one of the Druze. He spoke often on the international line, mostly with journalist friends.

Waite met with Mroueh again on Friday. No advance. Waite's nerves were getting ragged. It hadn't helped that a French journalist was kidnapped shortly after talking with him on the Comiche. Waite had taken to wearing a bulletproof vest. He told the press they were endangering his life.

Waite decided he needed dark glasses, as though that would prevent him from being the most visible man in Lebanon, and a leather jacket. (It can get fiercely cold in the Bekaa.) He went shopping on Beirut's once elegant Hamra Street, but complained he had no money. (His annual income then was something like £19,000.) He did try on some jackets in Red Shoe, a leather-goods store. ''We had nothing in Mr. Waite's size," an assistant told me. There was some bravado to this jaunt, because warnings were coming in from all sides. The British consul in Beirut bizarrely elected to deliver one such caution in schoolboy Latin. There was another profitless meeting with Mroueh on Saturday. Waite called Brent Sadler to say he was returning to Cyprus that weekend.

A typical Lebanese battle broke out on Sunday afternoon, though, between the Druze and another militia. "It was a traffic accident that escalated," says a longtime Beirut-based British correspondent, Julie Flint. Waite's return was aborted.

On Monday evening there was a further meeting with Mroueh. Waite was attended by one bodyguard. Others waited outside. He returned to the Riviera Hotel. Later a letter was delivered to him there. Waite announced that he was delaying his departure. He seemed in a buoyant mood.

On Tuesday he was picked up by the Druze escorts at 6:40 P.M. He insisted on completing his mission on his own. They drove him to the tiny coffee shop above a pebbly inlet that was a Druze base in Beirut, and called their headquarters. Their head of security wavered, but said that if it was Waite's wish, then so be it. Waite made a short speech. He said that he had to go on alone, that he would call at eleven that night, and that he was grateful for all they had done.

"I was sad," an escort told me. Why? "It was as if he was saying good-bye.

Waite also removed the battery from his watch. "Now nobody can say I'm wearing a bug," he told them. He was dropped off at Mroueh's apartment building. It has a beauty shop on the ground floor, and is next door to the headquarters of UNICEF, the United Nations relief organization, and opposite an apartment block, the Haykal Center. From one of these points an observer—not one of the Druze militiamen—was able to note that Waite was meeting with Dr. Mroueh and a leading Hezbollah fighter.

At half past seven Dr. Mroueh left his apartment building quickly, and alone. Waite wasn't seen, nor did he telephone, although the Druze waited until 5:30 A.M. At 9:30 in the morning Julie Flint was passed by a Hezbollah of her acquaintance. "You will not see him anymore," the man said merrily. She didn't need to ask who.

The next day, Dr. Mroueh was not answering his beeper. The Druze caught up with him in the hospital. His story was that he had been called out to help a patient deliver a baby and that Waite had been gone on his return. The Druze describe Dr. Mroueh as "very nervous." They held his wife and five-year-old child under house arrest for a while, but the doctor was too connected. Untouchable.

Five days later they caught up with the Hezbollah who they believed had organized the snatch. "A fly does not move in the southern suburbs that we do not see," a Druze chief told him. But he was immovable. "I have a cousin in Kuwait" was all that he would say. They released the man. He was untouchable, too.

Kuwait was the clue. The release of the A1 Dawa Seventeen had been the most consistent demand in all hostage negotiations, including Waite's. The envoy had been given the idea by the Americans that the release of the Hezbollah imprisoned in Kuwait might be effected, and he had met with some influential Kuwaitis. Waite is supposed to have told Hezbollah, "I have somebody in Kuwait," meaning somebody who could unlock doors.

"Khashoggi?" he was asked.

"I don't work with arms dealers," he replied. But while Waite's mission was well under way, Kuwait publicly reaffirmed that there would be no negotiations over the release of the A1 Dawa Seventeen. Many think it was this that sealed the envoy's doom.

This is the Middle East, though. Waite had still not given up on the Kuwait scenario, and some of his last telephone calls seem to have related to this plan. A close associate of Waite's says that the Kuwaiti announcement was just camouflage. "Terry was going to Kuwait two weeks after he left Beirut," the associate maintains.

But Hezbollah must have stopped believing Terry Waite. We think them to be ruthless and arbitrary. They believe themselves to be surrounded by dark plots. Consider Waite's telephone calls, which were taped, possibly by both Hezbollah and the Druze. I have read transcripts of the supposedly "suspicious" calls; all they suggest is that Waite didn't want to trumpet his doings on a notoriously open line, and used clumsy codes. Brent Sadler tells me that in Libya Waite would sometimes turn the shower on before talking, quite unnecessarily. What we would see as the behavior of a Boy Scout, though, Hezbollah saw as that of a spy.

The apparent clincher was this. Waite was always a man who loved electronic gizmos. "He bought a Walkman in '84," Sadler says. "He was the first man I knew to use a Psion Organiser." Sometime after Waite's kidnapping his captors waxed wroth about a bug they had found. They claimed it was a device to help U.S. Special Forces locate the hostages. A Syrian minister announced that it was the Soviets who had located this device. An Iranian cleric scoffed: "Only God knows what we are going to see next! We had seen everything except a radar-carrying priest."

Various published accounts refer to a bug implanted in Waite's body, woven into his hair, or embedded in a Bible. It is interesting that Charles Glass of ABC, who was kidnapped after Waite, was searched for a bug, although not closely ("They didn't check my orifices," he says). Hassan Sabra of Al Shiraa believes that there was no bug, that it was a Hezbollah pretext. It seems inconceivable to me that Waite's bug, if there indeed had been one, was anything other than reassurance for a worried man on his most dangerous journey. Hezbollah, of course, would have seen it differently.

Brent Sadler was among the first into Terry Waite's room in the Riviera Hotel after he disappeared. "I videotaped," Sadler says. "It had been left neat the way Terry always left things. It was still warm. It was a horrible feeling—like a house after a death."

The con men who have tried to make money out of the missing Westerners soon struck. Lambeth Palace paid out some $21,000 for a spurious lead. Other offers have abounded. A Muslim deputy is said to have asked $7 million for two bodies: the dead William Buckley and the living Terry Waite. It is remarkably un-Lebanese, though, that so little in the way of hostage spin-offs—photographs, letters, etc.—has been offered on the market. The captors are serious. Just one thing is moderately certain about the hostages, which is that of those that survive, some at least are now in the Bekaa Valley.

From Beirut to the town of Baalbek in the Bekaa is roughly a one-and-a-halfhour drive. The $1.25 billion hashish and opium-poppy crops had been harvested, and the tawny soil looked raw. Huge cutouts of the Ayatollah Khomeini lined the highway, interspersed with billboards of Lebanese mullahs and more secular icons, such as Paloma Picasso and the Marlboro Man.

Baalbek was unimpressive—mostly rudimentary two-story houses built from concrete blocks. Splendidly incongruous on a hillock on the left were the GrecoRoman temples which give the town its name. To the right a taller hill was surrounded by a wall above which rose towers and the spikes of a communications setup of considerable sophistication. This was a place well known to the world's intelligence community, if only by ominous reputation. It was the Sheikh Abdullah Barracks, chief military base of Hezbollah. It has certainly held a number of the Western hostages. Naturally, it was the venue of one of the innumerable dubious "sightings" of Terry Waite.

The bureau of Islamic Amal, one of Hezbollah's more visible entities, is a quarter of a mile below the barracks. I had come to ask for an interview with Islamic Amal's leader, Hussein Musawi, the Hezbollah often cited as the man with greatest heft where the hostages are concerned. The militiamen inside the bureau looked at me with bright, incredulous smiles, and spoke with my guide, who answered them with insouciance, and motioned me back into the car.

Musawi was in Damascus, he told me. But we had an interview for the morning of the day after tomorrow. What else had they been talking about?

"They ask, 'Is he not afraid to come here?' I said, 'Why? Musawi is saying he wants foreigners to come back to Baalbek.' "

He grinned hugely. The Lebanese dearly love a touch of Grand Guignol.

We returned for our appointment. Musawi is in his thirties, has very black eyes, smooth skin, an aquiline nose, and white teeth which he shows in a smile of unusual brilliance. A youth in a sweatshirt that read "City Rush" gave us macaroons and glasses of hot tea before our interview, which began crisply at the appointed time in a room furnished with Oriental rugs, framed Koranic texts, and a photograph of the Ayatollah Khomeini seated with an uncharacteristically benign expression in an orchard.

Musawi took a darker view of the changing relations between the West and the Arab world than his clerical colleague Sheikh Fadlallah. He saw "no improvement."

We got around to the Western hostages. The A1 Dawa Seventeen, held in Kuwait, the liberation of whom had been the longstanding precondition of the release of Western hostages, were free at last, and in a most unexpected way. They had escaped from their Kuwaiti jail in the turbulent hours following the advance of Saddam Hussein's army last August. But Musawi was dismissive. "They were not freed by the British or the Americans," he said. "It is irrelevant."

This was startling. What was relevant? I asked. Musawi echoed Sheikh Fadlallah.

"Iranian diplomats were kidnapped by the Christians," he said, referring again to the 1982 incident during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. "We do not know if they are alive or dead. The United States and Britain should help resolve this issue. Their hostages would benefit from this."

We stood up to go. Was it true that Musawi would welcome a return of Western tourists to Baalbek after fifteen years, I asked, just to lighten the atmosphere.

"Yes, yes. Many tourists," he said in English. "But no spies." He shot a glance at my feet. "You stand like a soldier."

"I was a soldier," I said. "But many, many years ago."

Musawi was, I decided, joking.

It is dreadfully Lebanese that the kidnapped Iranians should have replaced the A1 Dawa Seventeen as a dominant issue in hostage politics. It had been eight years since they had vanished at the Christian checkpoint, and the rumors were the usual Dark Baroque. According to one, they had been sold to Iraq for a million dollars, this being before prices escalated. One Christian leader recently claimed that they were still alive, and named the jail where his rivals were holding them. Two other Christian bosses, though, have claimed they were shot out of hand. Each blamed the other.

I went to the Iranian Embassy on the Comiche, another of the many places where there have been "sightings" of Terry Waite, and spoke to Mohammed Cherry, a burly man with a coy, careful manner. "We have heard they are still alive," he told me.

If they are dead, who gave the order? I asked him. He gave a heartfelt, bewildered shrug. Last summer Iranian representatives approached a Lebanese with good connections within the Christian militias and asked him to establish what had happened to their people. I have seen documentation of the request. They want evidence. It is a problem.

Other problems, though, are being solved. Britain did restore relations with Syria, just one day after the departure of Mrs. Thatcher, for instance. The Abu Nidal group announced in Mar Elias, its camp in Beirut, that it would free its four Belgian hostages, and did so in mid-January.

As I write, the situation with the remaining hostages in Lebanon is still unclear, especially with the Gulf War inflaming Muslim feelings. Syria continues to consolidate the peace in Beirut, but Iran's attitude toward the West is looking more ambiguous. I'd been told that there was a Syrian key and an Iranian key. But it was becoming increasingly plain that there was a Lebanese key also. The closeknit Hezbollah subgroups holding the hostages do not always see eye to eye, nor are they always as responsive to Iran as Washington believes. The hostages are in danger of becoming both a cash resource and a human shield. They and their captors are floating in suspense.

Their families too. I was speaking with Elham, the Lebanese wife of American hostage Joseph Cicippio, late one evening when her telephone rang. She listened with odd intensity. "That was my sisterin-law," she told me. "She says she heard on the news that Joe is dead." She was taut, wholly beyond tears.

We drove to Beirut's late-night international switchboard and called New York. The report had been wrong. It was another member of her husband's family who had died. "I hope Joe doesn't hear," she said. "It is lonely for him already."

"Nobody wants the hostage families. Nobody wants anything from us," Jean Sutherland told me without self-pity. Curled up at her feet was the cat that she inherited from John Leigh Douglas, a Briton, one of three hostages executed in retaliation for the bombing raid on Libya that killed Qaddafi's adopted infant daughter.

What will you do when your husband is released? I asked.

"I want to stay in Lebanon. I believe that Tom will, too," she said.

The attention of the West is focused on the Arab world as seldom before. Hezbollah could profit from these developments. This would require, though, that they get out of hostage politics and relinquish their foreign captives—such as are still alive— including that most miserable victim of Iran-contra, Terry Waite.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now