Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

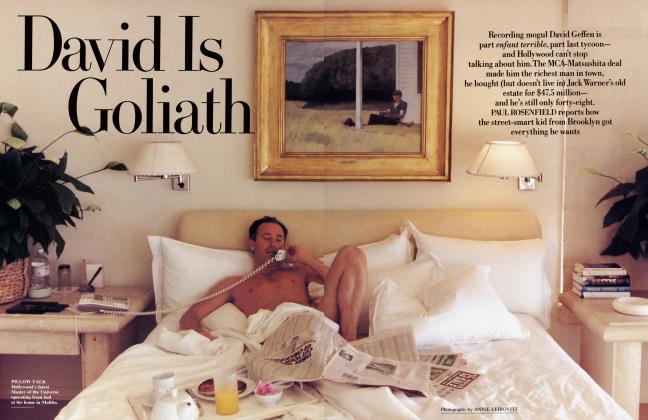

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHAMMER NAILED

Postscript

As an art impresario, Armand Hammer was more P.T. Barnum than Lorenzo de' Medici

JOHN RICHARDSON

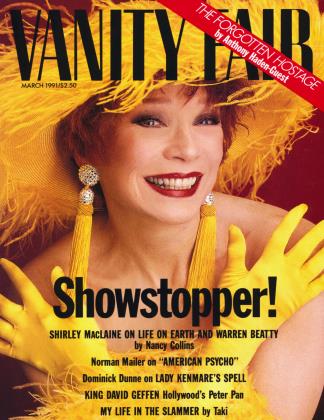

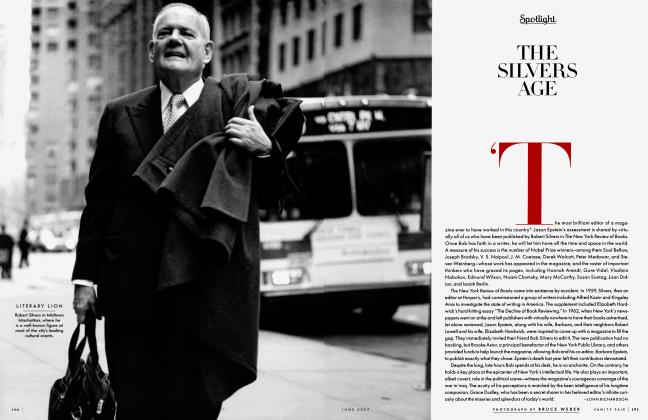

Whether the late Dr. Armand Hammer was the amalgam of John D. Rockefeller, Henry Kissinger, and Mother Teresa that he purported to be is in increasing doubt. He claimed to have convinced presidents, prime ministers, and princes—Deng, Zia ul-Haq, Edward Heath, Prince Charles, Begin, and Bruno Kreisky, not to speak of Brezhnev and Gorbachev— that he was Superman. He hyped himself as a public-spirited statesman who had saved the world by helping Roosevelt negotiate the Lend-Lease Act of 1941 and Reagan bring off his Reykjavik summit meeting with Gorbachev in 1986; as one of the most farsighted entrepreneurs of his day, who had built Occidental Petroleum (familiarly known as Oxy) from nothing into a $21 billion company and brought off the "deals of the century" (in asbestos, phosphates, and coal) with the Soviet Union and China; as a zillionaire philanthropist who devoted most of his money to cancer research; and as the last great collector of great art. Was all this, in fact, a sham?

To answer this question we have to penetrate the smoke screen in which the Doctor shrouded his beginnings. Armand Hammer was bom in New York on May 21, 1898, to a Russian Jewish family who had fled the pogroms in Odessa. Armand's mother, Rose, was a formidable young woman who worked as a sewing-machine operator in a garment factory. Armand's father, Julius, had rallied to Socialism as a teenage laborer in a brutalizing New Haven foundry, and he named his son after the Socialist Party emblem, arm and hammer—not after the romantic hero of Dumas's La Dame aux Camelias, as Julius sometimes claimed. When the family moved to New York he got a job in a Bowery drugstore, and before long had bought out the owner.

Julius was an enterprising shyster devoured by two seemingly irreconcilable obsessions: fervent Socialist activism (he later broke away from the Socialists and helped found the U.S. Communist Party) and rapacious capitalist ambition. By his early thirties he was a power in the Socialist movement; he was also running his own pharmaceutical company and a chain of drugstores. Like his son Armand he had few scruples. When he overextended himself, he declared bankruptcy in order to defraud his creditors, but no criminal charges were brought against him. He then became a doctor and set up a successful practice in the Bronx; his ultimate undoing was an abortion business on the side.

Many of the lies that Armand told about his father and himself have been exposed by Steve Weinberg, author of a recent, unauthorized biography, Armand Hammer: The Untold Story—which resulted in a suit for libel that ended with the Doctor's death. In later years Armand did everything to play down the fact—except when he was in the Soviet Union—that his Communist father had befriended leading revolutionaries at European Socialist congresses and, according to one of his comrades, was considered "the most discreet and able of Lenin's men of confidence." Why else would the Soviets have appointed Julius Hammer trade adviser to their bureau in New York?

Of all the skeletons in Hammer's closet, none rattled more insistently than that of the unfortunate Marie Oganesoff, wife of a well-off Czarist diplomat, who died in July 1919 as a result of Dr. Julius's botched abortion. The twenty-one-year-old Armand masterminded his father's defense a little too zealously. Weinberg reported that, in an effort to have Julius's sentence (three and a half to fifteen years in Sing Sing) commuted or lightened, Armand apparently employed a P.R. man at $100 a day to prepare a petition in his father's favor signed by several hundred physicians. When asked if some of these doctors were fictitious, the P.R. man refused to give answers, was found in contempt of court, fined, and sentenced. Armand subsequently tried to explain his father's offense away by invoking the influenza epidemic, anti-Semitism, Tammany Hall pressure, and even Czarist intrigue. Two years later, he persuaded Lenin that the charge of manslaughter in the first degree against his father was trumped up and that the government had been out to get him for founding the U.S. Communist Party.

Although Armand, like his father, obtained a medical degree from Columbia and was then accepted as an intern at Bellevue, he never actually practiced. Still, he always took pride in calling himself Doctor and having M.D. license plates. His father's ordeal conceivably encouraged Armand to abandon medicine, but the money to be made out of Julius's Allied Drug and Chemical Corporation was surely the determining factor. Young Hammer turned out to be a brilliant promoter—less of his father's surgical lubricants and saline laxatives than of a highly alcoholic tincture of ginger that pharmaceutical companies called "jake." Packaged as "medicine," this product sold so well during Prohibition that even before he received his medical degree Hammer was reportedly making $30,000 a day and employing 1,500 workers. This bonanza came to an end when jake was outlawed: thousands of people had suffered paralysis and some had died.

In 1921, Armand defied the American authorities and made his way to the chaotic Soviet Union. If you believe the myth he invented about himself, he was consumed by a philanthropic desire to alleviate famine in the Ural Mountains, but Hammer's motivation was probably twofold: to set up a new life in the Old Country for his ex-con father, and to establish himself as an import-export man. He would make philanthropy pay by shipping grain and the products of his pharmaceutical factory to the U.S.S.R. in exchange for furs, hides, bristles, hair, sausages, lace, rubber, and caviar. When Hammer was received in November 1921 by his father's old friend Lenin, the persuasive young capitalist easily sweet-talked the charismatic leader into accepting him as a suitable concessionaire, a bridge between East and West, between Communism and capitalism. The State Department kept a mistrustful eye on him.

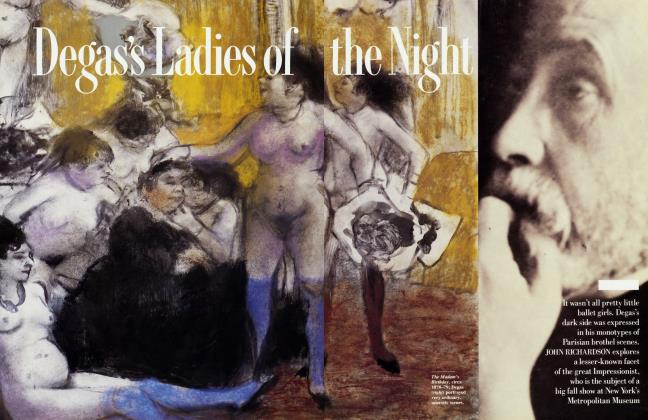

"Works of art" were a principal vehicle for the Doctor's worldwide ego trips.

On a return trip to Moscow in 1922, Hammer further ingratiated himself with Lenin by bringing him a present—a joke bronze of a monkey perched on Darwin's Origin of Species examining a human skull—that is still on exhibit in the Soviet founding father's preserved office. The gift helped win him an asbestos concession, the Ford Motor Company agency, and, eventually, a pencil factory. Hammer brought the rest of his family over to Moscow (including the newly released Julius) and set them up in the Brown House, a hideously ornate thirty-room villa that had belonged to a textile manufacturer. Farcical descriptions of parties at the Brown House enliven the pages of Eimi, e. e. Cummings's Joycean novel about a visit to Moscow in 1931. Hammer appears as Chinesey, a mysterious trader who "retires (eyefully) behind thick glass; becoming swollenly a submarine mind." He makes "remarks in handcuffs" and is guarded by "a mighty mastiff cur [that he] personally releases late each night... to keep the comrades out."

By that time, the Hammers were no longer trading in commodities such as hides and rubber but in what the Doctor subsequently dubbed "Czarist treasures." These "crown jeweled objects of art" were actually a very mixed bag: assorted icons, a few fine bits of Faberge, and storerooms full of lesser artifacts—the sweepings not so much of palaces as of hotels, restaurants, and junk shops. Despite its shaky provenance, the socalled "Hammer collection of Russian imperial art treasures from the Winter Palace, Tsarskoye Selo, and other royal palaces" did very well when put up for sale at Lord & Taylor and other U.S. department stores. Thenceforth "works of art" were not only a profitable business, but a principal vehicle for the Doctor's worldwide ego trips. I know; many years later I was a cog in his international art machine.

I did not take me long to discover that Hammer knew and cared as much about art as A1 Capone. His celebrated collection showed no discrimination whatsoever except in the one area— master drawings—where he had taken expert advice. Compared with the magnificent collections of old and modem masters put together over the same period by his neighbor Norton Simon, Hammer's pictures were uneven, mostly bargains bought for name, not quality. A handful, like Gauguin's Bonjour Monsieur Gauguin, are masterpieces, but he failed to weed out the many corny, ugly, or feeble works. Then again, instead of hanging them on his walls, Hammer preferred to use his paintings as bait for his traps: he lent them to Fort Worth in the hope of corralling rich Texans into investing in a questionable Peruvian oil field; to Beijing to help launch an opencast coal mine; to Edinburgh to curry favor with Prince Charles. Like good pearls without a decent neck to grace, his collection rapidly lost its luster. This was especially true of Hammer's most publicized acquisition: the Leonardo da Vinci Codex, a scientific treatise that he bought at Christie's London in 1980 for just under $6 million. By renaming this manuscript (hitherto known as the Leicester Codex, after the family that had owned it for generations) the Codex Hammer, and launching it into P.R. orbit complete with its own armed guards, the proud new owner effectively devalued it. When Time magazine's Robert Hughes pointed this out, the Doctor made vicious but unsuccessful efforts to have the art critic fired.

So long as one was not too closely involved, working for Hammer— above all, watching him fabricate something out of nothing—was entertaining. The boasts, the lies, the corners he cut! It was an education in chutzpah, in abracadabra—like being backstage at a conjuring show and seeing how the tricks were done. Hammer turned out to be a master of illusion, sleight of hand, and unctuous, guttural patter. Magic cloaks would transform the maestro from Mr. Magoo into a Nobel Prize candidate. Nothing had any credibility, except possibly the Doctor's friendly wife, Frances, who stood obediently in the wings, ready to distract attention from the trickery center stage, ready if necessary to be mesmerized or sawed in half.

I had been brought in to help run M. Knoedler & Company, the prestigious art gallery that a conniving employee had maneuvered into financial difficulties in the hope of assuming control. Hammer stepped in and snapped up the gallery. Luckily for me, he had persuaded my old friend Roland Balay, the last of the Knoedler dynasty and one of the best eyes in the art business, to stay on. He had also brought in a close associate: the colorful Dr. Maury Leibovitz, who practiced clinical psychology as well as accounting, the better to whittle down overweight women in the California fat farms that were one of his sidelines. The fourth member of this quartet was the genial Jack Tanzer, a sportswriter turned art dealer.

Tanzer spent weeks putting together deals of byzantine complexity. I loved listening to him on the telephone: Throw in the little Renoir to sweeten things, he would cajole another dealer, and the Doctor will let you in on the Eakins; or, Give us a half-share of the Canaletto and Warhol will do your wife. Tanzer could upgrade an indifferent Vlaminck into two Stellas and, after a few more permutations, end up with a Rembrandt drawing. Hammer greatly admired this ability. He was especially thrilled when Tanzer discovered how to turn several unsalable old masters into a very profitable asset. Tanzer knew that Walter Chrysler Jr., an unscrupulous collector whose excessive tax deductions for works of art were thrown out by the I.R.S. even more often than Hammer's, urgently needed to acquire paintings of established value. Knoedler's had just the thing: venerable daubs that had been listed on the books as worth millions of dollars but whose authenticity had recently been questioned by modem scholars. Chrysler took the lot in exchange for a superb Cezanne. A deal after Hammer's own heart: nothing tickled the old tortoise like getting something for nothing.

Hammer condemned Colonel Qaddafi's rapaciousness but also praised his "uncanny cleverness, idealism, perhaps fanaticism."

Hammer was full of surprises, not all of them unpleasant. His Godfatherish taste had not prepared me for the charm of his New York abode: a carriage house on West Fourth Street where he had lived since 1919. Nothing much appeared to have changed since the early twenties: the rooms were reassuringly cozy and seedy; whoever lived there could not be all bad.

The house in Los Angeles (Holmby rather than Beverly Hills) where the Hammers spent most of their time had much less appeal. Frances and her first husband, a rich man from Chicago named Elmer Tolman, had bought it from Gene Tierney when she was married to Oleg Cassini. This was its only distinction. Although Hammer always described his wife as an artist, her taste was Middle America at its most motelish: 1950s Sunbelt furniture and plastic flowers that needed dusting. (In those days Frances apparently did most of the cooking and cleaning. Later, there would be servants.) After Hammer visited Beijing, the decor became much more ornate—Chinesey. Down a spiral staircase from their bedroom was a dank indoor pool where the old tortoise did his lengths every morning at six A.M.—bareass because "it feels better," he said. For all that Hammer regarded J. Paul Getty as an exemplar, he never emulated the richer man's extravagant life-style. Hammer's principal indulgence was overaccessorized, oversize automobiles: Cadillac Fleetwoods, until he persuaded the Chinese to let him have Marshal Lin Biao's black Mercedes 600—the Pullman model.

I had been warned that there was no art chez Hammer, so I was all the more surprised by a large daub on the stairs—an unmistakably fake Modigliani. "Isn't that a great painting?" the Doctor asked, a saurian glint in his eye. I tactfully mumbled, "Interesting," which he chose to interpret as admiration. "That painting fools all you experts," he growled. "It's a copy by Frances." His wife, a Titian-haired matron in a vintage Pucci, stirred her iced tea, preening. I longed to ask whether she was responsible for some of the other fakes in the Doctor's collection, like the amateurish "Van Gogh" Sower. The only other "work of art" I remember in the house was an engraving after Hammer's Rembrandt, with his wife's face substituted for Juno's.

Frances was the best thing about the Doctor. In every way she was his opposite—unassuming, straightforward, and not very bright—and proved an effective foil, unlike his two previous wives. The first had been a well-known Russian entertainer, Olga von Root, whom Hammer had discovered singing Gypsy ballads in a Yalta cabaret. They were married in 1927, and in 1929 she bore Hammer his only child, Julian. The boy was raised by his mother, a loving but feckless character, and shamefully neglected by his father, which may explain Julian's subsequent outburst of extreme violence:

On May 7, 1955, Julian celebrated his twenty-sixth birthday by getting very drunk with his college roommate, Bruce Whitlock, a Golden Gloves boxing champion. At dinner they began fighting over a small debt, and back home in front of his pregnant wife, Glenna Sue Ervin, Julian shot Whitlock dead with a pistol.

When Julian was arraigned for murder, Armand hired a brilliant counsel, Arthur Groman (who would later head Hammer's team of lawyers), and apparently invoked the clout of his influential friend Senator Styles Bridges. The murder charge was set aside on grounds of self-defense. (Later, Julian was confined for some time in an institution.)

Meanwhile, Hammer had long since tired of Julian's theatrical mother and divorced her (she received $300 a month in alimony). A few weeks later, he married Angela Carey Zevely, an aspiring opera singer who had lost her hearing and taken to the bottle. According to Steve Weinberg, Angela was foolish enough to give Armand a 50 percent share in Nut Swamp, her New Jersey farm, where she and Armand began raising Aberdeen Angus cattle. Later, in 1954, when relations had cooled between them, Angela suspected she was being swindled and filed for an official separation. Hammer sued for divorce. She claimed that Armand had tried to beat her brains out. He counterclaimed that after a cattle auction she had got drunk and abusive and later threatened to bum his eyes out. After prolonged court proceedings, Angela was awarded $l,000-a-month alimony, but she got her revenge: she apparently made off with Armand's most valued possession, three handwritten letters from Lenin and an inscribed photograph.

Armand would always chase after pretty women. In his late eighties he went to considerable lengths ingratiating himself with a young woman who worked in Occidental's Beijing office. He was also assumed to have been very attracted to his comely "curator," Martha Wade Kaufman, who is said to have exerted a considerable influence over his declining years.

What Armand liked best were redheads; hence his enthusiasm for JeanJacques Henner, the nineteenth-century French painter of kitschy, auburn-haired nudes. "It's the flesh tones" was all I ever heard him admire in a painting. He liked to croak this phrase in front of the only modem American work of any value in his collection: Day Dream, Andrew Wyeth's heavy-hipped Helga demurely seen through a mosquito net.

Frances Hammer's attraction was more than her red hair. Elmer Tolman had left her a sizable fortune, with which she staked Armand to his original shares in Occidental shortly after they were married, in 1956. Another asset was Frances's garden-club demeanor, just the thing to give her husband the credibility he sorely needed. She came across as if she had taught domestic science in a nice New England school. Frances's reassuring warmth compensated for and to some extent camouflaged her husband's callousness to people who were of no use to him.

Nancy Reagan made her distaste for Hammer clear. When he begged for an invitation, she looked at him icily and just said "NO."

Hammer had summoned me to his Califomia home to discuss a problem. Soon after taking over Knoedler's, he had discovered a Goya in the stacks: a dreary but authentic portrait of Dona Antonia Zarate valued, I seem to remember, at around $150,000. He had hastily removed this painting from the gallery's stock and shipped it to Leningrad. The Hermitage did not own a Goya, and Hammer, who was still consolidating his Russian power base, planned to squeeze every last drop of prestige out of this "million-dollar gift from my private collection." To publicize the presentation of the Goya, he had insisted that the Hermitage exhibit his lackluster collection. He had also insisted on a quid pro quo. "What should I request in exchange for the Goya?" the Doctor asked me. "I have more than enough busts of Lenin."

"A Suprematist painting by Malevich," I told him. "The storerooms of Russian museums are full of them. Since the Soviets refuse to exhibit them, try and get one for your collection." Although he had been living in Moscow at the height of Kazimir Malevich's fame, this great collector had never heard of the man who is arguably the most innovative Russian painter of this century. "Suprematism? Constructivism? Forget it!" However, as I described how rare and valuable Malevich's paintings were, how high they stood on every modem museum's list of desiderata, and read him the relevant passages in Camilla Gray's book on modem Russian art, Hammer's distaste turned to avarice. He had to have one.

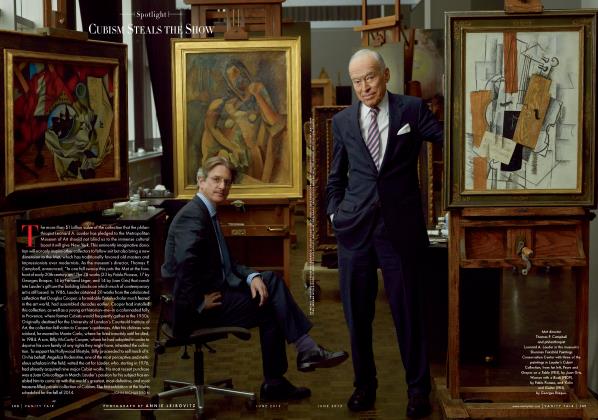

Since Hammer had apparently suborned Yekaterina Furtseva, the minister of culture, his request was her ukase. To their dismay, the curators of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow were bidden by the minister to disgorge a major early work, Dynamic Suprematism. True, it was a painting that was not in the best condition, but it was far more desirable than the third-rate Goya that Hammer had given Leningrad. The curators were flabbergasted when they later heard that Hammer had put their Malevich— the painting for which he had made a special request—on the market.

Long afterward, I learned that Hammer had submitted the painting to the world's leading expert on the artist, who confirmed that it was an important example of early Suprematism, albeit in less than perfect condition. The expert gave the same verdict to the director of a German museum, to whom Hammer had offered Dynamic Suprematism. As a result, the museum turned it down. At this, Hammer flew into a rage: he unleashed his squad of high-powered lawyers on the scholar. He did not call them off until the painting had been sold for $750,000 to another German museum.

So much for Hammer's art patronage. His excuse that he loathed the painting—the only major example of the modem movement in his collection—is the more ironic given the way he pushed in Moscow and Washington to have his new museum open last November with the prestigious Malevich retrospective currently touring the U.S. As usual, Hammer got his way, but the fact that the distinguished curator of the exhibition refused to sign her name to the catalogue, that neither of the directors of the other museums involved (the National Gallery of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art) showed up at the L.A. opening, and that American institutions withdrew their art loans is a measure of the respect in which this "modem Medici" and his museum were held.

Hammer was as piratical in his dealings with his friends the Soviets as he was with the West. This was one of the more entertaining revelations of a trip I took to Russia with the old tortoise in March 1975. The purpose of our visit was to negotiate a loan exhibition of masterpieces from Russian museums to the National Gallery, Knoedler's, and various American museums, chosen ostensibly by the Russians but in fact by Hammer. J. Carter Brown of the National Gallery came along; so, as usual, did Frances Hammer and a team of cameramen from the Doctor's film company, Armand Hammer Productions (a subsidiary of Oxy).

A principal purpose of A. H. Productions was to record the Doctor's triumphant progress from audiences with one world leader to another. Press photographers likewise hovered, and if the record was not to his satisfaction, Hammer, it is said, employed someone to retouch people into or, more often, out of photographs. In this respect—the rewriting of history—he followed official Soviet practice. Had it suited him to have met Stalin, he would have boasted of it. Since it did not, he always denied having done so, although Sovietologists doubt whether Hammer could have remained a power in the U.S.S.R. without direct access to the dictator. Hammer was equally ambivalent about Libya, Oxy's primary source of oil for some years. Hammer denied soliciting a meeting with Qaddafi. In fact, he never ceased in his efforts. He condemned the colonel's rapaciousness on some occasions and on others praised his "uncanny cleverness, idealism, perhaps fanaticism."

Shortly before our trip, Hammer had finally succeeded in consolidating himself with Brezhnev. Among other ingratiating moves, he had given the Soviet leader a couple of Lenin's letters purchased from a New York dealer. The Doctor's gift, coupled with the emergence in the Kremlin archives of Lenin's written approval of his business projects, had made him persona gratissima with the Soviet hierarchy. Whether Hammer spent much more than an hour in Lenin's company has been questioned by historians, but what counts is the old operator's entrepreneurial genius in parlaying this contact into a power base fifty years later. No less astute was Hammer's realization that the entree to Brezhnev could be further parlayed into a laissez-passer to the White House and the State Department, thence to No. 10 Downing Street, the Ely see, and even the Great Hall of the People.

We flew to Moscow in the Doctor's private jet, Oxy One, at that time the only noncommercial plane allowed into Soviet (and later Chinese) airspace. Hammer had obtained this privilege, of which he was childishly proud, through Cyrus Eaton, the maverick capitalist from Cleveland, who had forged close ties with the Russians long before the Doctor's second coming. In gratitude, Hammer arranged employment for Cyrus Eaton Jr. This did not last long: once Hammer had plugged himself into the Eatons' powerful Soviet contacts, he fired him.

While he was conspiring to disinherit his wife's heirs, Hammer was in frantic pursuit of the Nobel Peace Prize.

After Oxy One taxied to a halt at Moscow's Sheremetyevo airport, an Oxy representative came on board with unwelcome news. The recent downfall of Furtseva, over financial malpractice, had deprived the Doctor of a key ally. Her successor evidently wanted to distance himself from Hammer and his incriminating largess. Hammer found himself foisted off with a mere thirty minutes—not nearly enough to discuss the complicated protocols that his cultural exchange involved. From the defiant way the Doctor stamped off the plane, he had evidently seen how this reverse could work to his advantage.

Off we sped in the cortege of Chaika limousines that had been drawn up on the tarmac. In lieu of the usual customs checks, the cars containing our luggage took two hours longer than we did to reach the old Hotel National just off Red Square. Brezhnev had not as yet awarded Hammer the privilege of a grace-andfavor apartment of his own near the Kremlin, his headquarters in later years, but he already had a large office as well as use of the depressing "Lenin suite" in the dingily grand Hotel National. To prevent the bugs in the chandelier from picking up the Doctor's gravelly voice and getting wind of his tricks, the TV was always on full blast.

A day or two later, we assembled in the ministry of culture, camera crew and all. Hammer proceeded to waste twentyfive of his allotted thirty minutes on needless formalities and photo opportunities. He had himself filmed again and again presenting the minister with one of the Russian "masterpieces" he kept on his plane for these emergencies. Although his Russian was quite fluent, he constantly spoke through an interpreter, giving himself extra time to maneuver. Hammer told the minister that lack of time for discussion was of no account; they were obviously in agreement and could go ahead with the signing of the protocols in the presence of the American ambassador that very afternoon. Armand Hammer Productions would be filming this historic cultural event for American TV.

The minister fell into this trap. Later that day, in the glare of arc lights, the wretched functionary went ahead and signed the contracts which, as he realized too late, the Doctor had covertly doctored. Among other concessions, Hammer claimed to have obtained the copyright to the Russian paintings for as long as they were in America.

Knoedler's was not the profitable modem gallery it is today, but its prestigious reputation—especially in comparison with the Hammer Galleries, headed by his brother Victor—was something the Doctor used to enormous advantage. It provided him with a venue for two great Russian loan shows as well as a respectable base for his ambitions as an art patron. The gallery's London branch also came in useful: in 1977 it was the setting for one of the most productive encounters of Hammer's later life. To celebrate the Queen's silver jubilee, he had organized an exhibition of Winston Churchill's amateurish but flamboyantly impressionistic landscapes. Prince Charles was enticed to the opening so that Hammer could lay siege to him. Though at first he had no success, he soon snared the heir to the throne by presenting him with one of the great statesman's canvases.

For the rest of his life, the Poloniuslike Doctor poured honey into the royal ear and money into the more newsworthy royal charities: the senseless raising of the Mary Rose, a man-of-war that had sunk in 1545; British explorer Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes's Transglobe Expedition, which was filmed by Armand Hammer Productions (cameo appearances by Prince Charles and the Doctor); the re-creation of Shakespeare's Globe Theatre; and—most costly and ambitious of all—the development of United World Colleges, the brainchild of Kurt Hahn, former headmaster of Prince Charles and his father, Prince Philip. (In the 1930s this autocratic German educationist founded a private—what the English call a public—school in Scotland called Gordonstoun; its supposedly newfangled principles were in fact old-fashioned German ones given a new look.)

At first sight United World Colleges would seem an odd cause for the son of the Communist Julius Hammer to espouse. But the Doctor had a deep-seated respect for authority (he showed no sympathy for the students in Tiananmen Square). He was also prepared to go to any lengths to oil up to Prince Charles. And so he threw himself into establishing the first American United World College, in an abandoned Jesuit seminary way up in New Mexico's Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Soon after the school opened in 1982, Prince Charles dutifully flew in, and one of his cousins, King Constantine II of Greece, was prevailed upon to allow his son to study there.

In 1985, Prince Charles dutifully flew in once more, this time with Princess Diana, to preside over a United World College charity ball that the Doctor was organizing in Palm Beach. Hammer was a demon fund-raiser (with Jerry Weintraub and others he helped raise over $60 million at a Los Angeles benefit for Israel), and he had no problem conjuring millions out of the prosperous Palm Beachers. (For $50,000 a go, upwardly mobile philanthropists could have themselves photographed with the royal couple.)

Nevertheless, the ball was a debacle. For all his dependence on public relations, Hammer had no social sense— force majeure was more his line. The leaders of Palm Beach society were outraged that a Russophile out-of-towner should exploit the British royal family at their expense—and all for a cause that didn't have the slightest local appeal. The city fathers refused to issue a permit to solicit funds—until $75,000 had been paid into their coffers. Worse, instead of having some local grande dame chair the event, Hammer chose cheesecake: the partly Iraqi Patricia Kluge, whose husband served on the Oxy board. When it was revealed that this monumental beauty had posed nude for a number of English sex magazines, certain susceptible ladies decided to boycott the event. Governor Bob Graham's declaration that the day of the ball would be Armand Hammer Day was the final indignity.

Cozying up to Hammer earned Prince Charles as much as $14 million for his charities, but little respect for his judgment. As recently as the summer of 1989, Hammer extracted another fundraising quid pro quo from the Prince: a jaunt for some of his California and Canadian cronies that included lunch at High Grove (the Waleses' country house), a polo match at Windsor Castle, and dinner at a ducal house. Rumors even circulated that the Doctor expected the Waleses would invite him to be godfather to their second son, Henry. This did not come to pass, but many people had begun to realize that anyone who fell under an obligation to the Doctor would ultimately be placed in the position of Faust vis-si-vis Mephistopheles.

Hammer's admirers saw him as a bridge between East and West Except insofar as he collected tolls, this was an illusion.

Even the Reagans had difficulty keeping Hammer at bay. According to Weinberg, back in Beverly Hills, Ronald Reagan had been irritated to find Hammer always ensconced in the next barber's chair when he went for a haircut. In Washington the Doctor was even more of a pest—constantly badgering the president to pardon him for having made a hefty illegal contribution to Richard Nixon's re-election campaign. Although Richard V. Allen, Reagan's first nationalsecurity adviser, did his best to block Hammer, he rushed up at functions and refused to go away until he had his say. Nancy Reagan was appalled by Hammer's aggressive buttonholing. She made her distaste for the man very clear, not least at the Moscow summit in 1988 when he begged her for an invitation to the state dinner at the U.S. Embassy: she looked him icily in the eye and just said "NO."

But even the First Lady found herself outflanked when Hammer gave substantial donations to her anti-drug campaign and White House redecoration fund as well as a scholarship—in memory of her father!—to the American College of Surgeons. He also presented the White House with a western painting by Charles Russell belonging to the Hammer Galleries, supposedly worth $700,000. Though a pardon was not forthcoming, the Reagans could no longer keep the Doctor out of the White House.

George Bush was more of a pushover. As a reward for a sizable contribution, Hammer was given a place of honor at the inauguration, next to the Reagans and Quayles at the top of the Capitol steps. Two days before, he had held his own inauguration: the unveiling of the self-promotional papers he had given the Library of Congress—yet another ploy in his bid for the full presidential pardon that Reagan had adamantly refused. Hammer finally scaled down his plea from a pardon that conferred innocence to one that granted forgiveness. Bush gave way and granted Hammer his wish, despite the fact that he had pleaded guilty at his trial; had an appalling record of indictments by the Federal Trade Commission and Internal Revenue Service; had copped a light plea (a $3,000 fine and one year's probation) instead of a three-year prison term; had apparently faked mortal illness (in a wheelchair hooked up via a monitoring machine to a cardiovascular team in a neighboring courtroom); and had failed to express the customary remorse.

The Doctor did not confine his hypocrisy to corporate affairs. He was equally ruthless with his family. In 1970, Harry, eldest and least colorful of the Hammer brothers, died two years after his wife, Bette, who had left him her family home in Mississippi, with the written intention that this should go to her sister, Frances Colmery. Hammer, who was Harry's executor, insisted on a payment of $40,000. When the indignant sister refused, he let someone else have it for $22,000.

Even more reprehensible was his treatment of his younger brother, Victor, an endearing buffoon who had spent his life loyally catering to Armand's dictates. With his perpetual smirk and patter and stage-door-Johnny outfits (he was never seen without a white bow tie and a white carnation), Victor resembled a ventriloquist's dummy, and indeed he often served his brother in that capacity. Victor originally wanted to be a Jewish comedian, but neither his father nor his fearsome Mama Rose would hear of it. Armand used these aspirations to his own ends. After setting up shop in Russia, he needed office help, and he enticed Victor to join him by promising that he could study at the Moscow Arts Theater. That celebrated institution never got the chance to train Victor for the Borscht Belt: the would-be performer was obliged to learn typing and shorthand, and spend his days monitoring Armand's pencil factory and inventorying the "Czarist treasures."

Back in New York, Victor was put in charge of the Hammer Galleries. When the gallery's Soviet sources dried up, Victor switched to minor Impressionists, western art (then relatively undervalued), and later the work of Grandma Moses. Armand subsequently claimed that he was always having to bail his brother out of financial trouble, but few dealers were better at selling very late, very small Renoirs to very minor collectors.

In 1941, Victor married Ireene Seaton Wicker, a fey entertainer who starred as "the Singing Lady" on a children's radio show. In 1950, she was blacklisted for entertaining Spanish refugee children and singing Russian Gypsy songs on the air. Armand was terrified that her reputation might compromise him, and he disapproved when Victor kept Ireene's wrecked career afloat by buying her radio time into the mid-1970s. (The Singing Lady had far more success with Andy Warhol, whom I brought into the Knoedler stable. "Wow, not the Singing Lady!" he gushed, thrilled to meet this much-loved relic of his childhood. "Come and sing at the Factory." The Singing Lady, however, had not sunk to performing in factories: Andy got a very disdainful sniff.) By the time I met Ireene, she had faded into an ancient child out of a Diane Arbus photograph. Her finery and the many quaint rings she wore had a dusty, tarnished look that no amount of Vuitton luggage—her one and only status symbol—could exorcise.

Armand was only slightly less contemptuous of Ireene's husband, but then, Victor could still be useful, primarily with the Roosevelt family, whom the Doctor was forever courting, even to the extent of buying Campobello, their white elephant of a summer home. Eleanor Roosevelt mistrusted Armand, but had a soft spot for Victor and Ireene. To please them, she would occasionally anoint the Doctor with faint praise that he would magnify into an accolade.

When Victor died, in July 1985, he left Ireene over $1 million in assets, including a $400,000 house in Stamford, Connecticut. In his role of executor, the Doctor proceeded to disinherit the aged, ailing widow: he claimed to have lent Victor as much cash as there was in the estate; he refused to pay Ireene's nursing-home bills, and took steps to sell the family house over the head of Ireene's daughter, Nancy Eilan, whom Victor had adopted. To protect her mother, Nancy played the only card left to her: going public. It was a mistake. By prolonging the case, Hammer used up what was left of his sister-inlaw's savings. Then, all of a sudden, after Ireene died in November 1987, the case was settled, to everyone's amazement, out of court. Nancy got to keep the house.

Had Hammer had a change of heart? Apparently not. It seems that Frances Hammer's confidence in her husband's character had begun to erode. By 1987 she could no longer put up with the perpetual traveling (three continents in two days was typical of his schedule). Left alone, she is said to have brooded about her ninety-year-old husband's continuing susceptibility to female company. And after Armand's treatment of Harry's and Victor's dependents, she seems to have worried about the fate of her own considerable fortune. If she died first, would her family, notably a favorite niece, be treated as shabbily as Ireene and her daughter?

Hammer's sudden settlement with Victor's stepdaughter suggests that he was out to set his wife's mind at rest on this score. It was too late. On May 12, 1988, Frances Hammer made a new will—this time she decided to use a California lawyer who had no associations with Hammer or his enterprises. All Frances's separate property and her halfshare of community property would now go to her niece, Joan Weiss.

The new will threatened to annihilate the Doctor's dreams of posthumous glory. As of 1988, these took the form of a private museum. Hammer had recently told the trustees of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, to whom he had promised his collection, that they would have to acquiesce to the following terms: the collection would be required to form a museum within a museum, housed in a separate wing of LACMA in galleries from which the names of other donors would be erased; the collection would have its own curator (presumably Martha Kaufman), answerable only to Hammer or his representatives; and, last but not least, there had to be a large portrait of the Doctor on permanent display in the main entrance hall of the gallery. When LACMA understandably refused these demands, Hammer announced he was establishing his own museum. He lost no time in commissioning a mausoleum-like building to be erected next door to Oxy's head offices in the Westwood district of Los Angeles.

Frances's half-share of the art was crucial to this project. So was the collection of fifty mostly minor old masters (including two Rubenses and a beautiful still life by Rembrandt's pupil Gerard Dou) that Hammer had presented to the University of Southern California in the 1960s. When he offered to buy them back, U.S.C. was agreeable, subject to a new, independent appraisal. Negotiations stalled when the appraisers (Sotheby's) said they would submit their valuation only if Hammer undertook not to sue them. Hammer refused to comply with this condition.

Another problem: who would foot the bill—said to be $96 million—for the cost of building this museum? Several of Oxy's shareholders were fed up with underwriting the vanity of a megalomaniac who owned less than 1 percent of the corporation, and sued Hammer and the directors of Oxy for squandering corporate funds. The stockholders had further cause for dismay when they discovered that the corporation, and not Hammer, had bought some of the art, specifically the Leonardo Codex, now incongruously installed in the new building, in what purports to be a shrine. When the shareholders realized that the museum might not be getting Frances's half-share of the collection, they had reason to be even more concerned.

There was no time to lose: Hammer had to induce Frances to renounce her interest in the art collection. According to a complaint filed on behalf of her niece, Joan Weiss, the Doctor came up with three separate waivers that Frances was somehow prevailed upon to sign in the few months before she died, on December 16, 1989. Since Frances was allegedly not apprised of the property rights she was signing away, her niece's lawyers contend that these disclaimers are unenforceable, especially since, they claim, his wife had no access to independent legal counsel. (Hammer's lawyers deny these allegations.)

Despite these legal tangles, Hammer raced to get his new museum built. A ceiling of $60 million, plus a $36 million annuity, had been imposed as a result of the shareholders' lawsuits. The Doctor's great age and seriously declining health made for further problems. The building—a squat cube horizontally striped like a Carvel ice-cream cake— was barely ready in time for the opening of the Malevich show last November. Certain facilities—notably the auditorium—remain unfinished. To raise funds, Martha Kaufman, who had recently Anglicized her name to Hilary Gibson, organized a series of "hard hat and caviar parties." These activities reinforced Hammerologists' view that Kaufman was taking over—an impression backed by a recent court filing on behalf of Frances Hammer's estate alleging that Mrs. Hammer agonized over the "personal and professional relationship" between her husband and Kaufman. Frances Hammer's observations concern Kaufman's alleged "ambitions for advancement in organizations controlled by Armand Hammer and. . .details of claimed sexual activity with him."

While he was conspiring to disinherit his wife's heirs, Hammer was in frantic pursuit of the one honor he really coveted: the Nobel Peace Prize. His philanthropic ventures were increasingly directed toward this end, but his record proved as resistant to cleanup as Love Canal—a headache he had inherited when he obliged Oxy to buy Hooker Chemicals in 1968. After Hammer was named to the President's Cancer Panel under Reagan, Mother Jones declared that Sid Vicious might as well head a program for battered women, or Qaddafi direct the Jewish Relief Fund. As for the annual Armand Hammer Conference on Peace and Human Rights, the first of which significantly took place in Norway (Nobel land), it generated nothing but hot air—much of it mindless adulation of Hammer. "If [the prize] can be bought," said Zbigniew Brzezinski, Carter's national-security adviser, "his chances of winning it are quite high."

After he reached ninety, Hammer started to falter. At the best of times this incomparably canny man had known very little about history or economics (let alone art or literature). Now he no longer remembered whether he was in Bonn or Berlin, whether to address Zia and his Cabinet as Muslims or Hindus, whether there had been a war in Korea. He was also in appalling pain, so much so that he was often accompanied on his travels by an anesthesiologist, Rosamaria Durazo, who did a great deal to relieve his suffering. Even people who could not abide Hammer were astounded by the courage and energy he showed in his last years. Five days after openheart surgery at the age of ninety, he was back at work in his office. "How could you not admire his guts?" someone who had suffered under the old con man asked. He may have been inhuman, but there was a superhuman side to him.

There was even a certain heroism to this senile pirate's defiance of death. Last year, at the age of ninety-two, Hammer informed friends that he had just bought twelve new suits and twentyfour pairs of pants. He also organized a mammoth fund-raising party to celebrate his return to the Jewish faith. What more appropriate pretext than a Bar Mitzvah, something his agnostic father had denied him? But God withheld His blessing. On the eve of the ceremony, He gathered Armand Hammer before he could glorify himself at His expense.

Hammer's admirers saw him as a bridge between East and West. Except insofar as he collected tolls, this was an illusion. Given the way Hammer ran Oxy as a private fiefdom, it is not surprising that its shares shot up nearly two dollars the day after he died. As well as planning to divest itself of $3 billion worth of assets, including many of Hammer's pet projects, as Oxy is currently doing, the corporation should perhaps take inspiration from Lenin's tomb and turn its redundant museum into a mausoleum. The words "He who hath the gold maketh the rule," which were inscribed on a plaque in the Doctor's bedroom, would make an appropriate epitaph.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now