Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHIGHBROW FOR HIRE?

Is Anthony Burgess, publishing a second volume of tormented memoirs, better than he thinks he is?

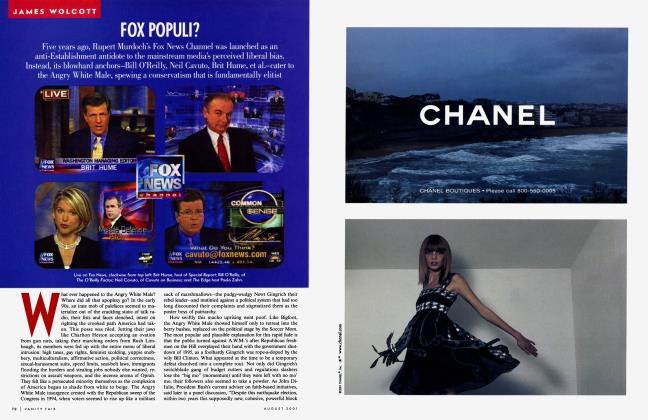

JAMES WOLCOTT

Mixed Media

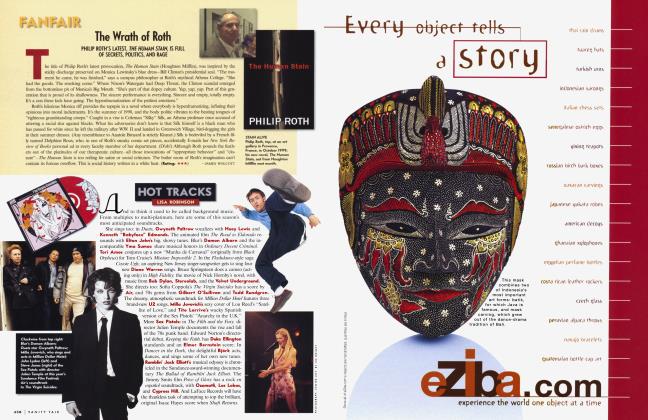

Anthony Burgess has a lot going on upstairs. He's brilliant, learned, and musical. Like Joyce or Nabokov, he can toss a leafy salad comprising several languages. Off the top of his head he can tap-dance on almost any topic. But if Burgess is fluent, he's far from flighty. He has the work habits of a plow horse. "The practice of a profession entails discipline, which for me meant the production of two thousand words of fair copy every day, weekends included." Two thou a day equals 730,000 words a year—a ton of yardage. Along with dozens of novels (among them the Enderby series, A Clockwork Orange, and Earthly Powers, his magnum opus), he has composed screenplays, librettos, symphonies, children's books, critical studies of Joyce, Shakespeare, Hemingway, and D. H. Lawrence, and reams of commentary. Bom in 1917, Burgess is now unloading his personal backlog. A few years ago he wheeled out the first volume of his autobiography, Little Wilson and Big God. (The "Little Wilson" of the title is Burgess himself, his full name being John Anthony Burgess Wilson.) Next month welcomes its follow-up, You've Had Your Time, published by Grove Weidenfeld. You've Had Your Time doesn't find Burgess basking in success, enjoying the sunset. True to its title, the book is a bit testy. Its dissatisfactions form a gritty abrasive. But as long as you're bitching, you know you're alive.

Death has kept Burgess company from the outset. According to Little Wilson and Big God, his father came home from the First World War to find his wife and daughter dead of influenza, baby Burgess alive on his cot. His father remarried, and Burgess was raised Roman Catholic, steeped in guilt, sacred mystery, and resentment, the whole Stephen Dedalus package. In 1959, Burgess was diagnosed as having an inoperable brain tumor and was allotted a year to live. Faced with a death sentence, he flung himself into literature, totaling five and a half novels that fatal year—"very nearly E. M. Forster's whole long life's output," he wryly notes. But the year passed, and death didn't knock at the door. Some doctor had bungled the diagnosis. The ceiling lowering over his head turned into pure sky.

Not that he was home free. From his fiction he earned feeble amounts. And his married life was a forced march into misery. His Welsh wife, Lynne, was a bitter lush. A snarl in the next room, a staggering embarrassment, a public reprimand. (Kingsley Amis and Gore Vidal have both described catching grief from her at parties.) Lynne wasn't merely a bad choice, or an accident waiting to happen. She, insists Burgess in You've Had Your Time, is typical of her species. Women resent men's upward thrust toward art. "Artists are acceptable to women when they are dead—they become an ornament they can pin to their smart black—but they are a nuisance when they are alive, because they are devoted to a rival. Women are not permitted to take art seriously when they themselves practise it, for they recognize that it is a mere surrogate for the creative miracle of bearing children." That tired old line! (If books are baby substitutes, Joyce Carol Oates has given us a cabbage patch.) He even dusts off the old bluster about how what these women really need is to, um, unwind. "It would have done her good to be seduced in a Manchester back-alley," Burgess writes of Virginia Woolf. He says "seduced," but rougher medicine seems implied.

Lynne, who had been assaulted by four G.I.'s in a London blackout and was unable to bear children, didn't need to unwind. She was already unwound. When Lynne wrapped her oily tentacles around other men, Burgess retired from the fray rather than compete. Booze was his alibi. "If, at night, I was too drunk to perform the act and, in the morning, too crapulous, it was probable that I soaked myself in gin in order to evade it." Lynne wasn't buying it. To her, hubby dear was backing into the closet. In Tangier she accused him of lusting after little boys, then had the hotel doctor sedate him. "I passed out and woke late with a parched mouth. This was no way to spend a holiday." After the success of A Clockwork Orange, Burgess was able to attract a groupie, but this too took an ugly turn. ''I watched her forking in her chefs green salad ('Go easy on the garlic, okay?') and noted the budding herpes on her lip." He was meant to be married, even if this meant hell.

Lynne tried to keep up appearances. ''She seemed well, even comely, when the cosmesis of a wig, to cover hair that had lost lustre, and a caftan, to hide what I did not yet know as ascites, were applied for literary parties." (I don't know why, but that "comely" strikes me as the cruelest word in the book.) She also tried suicide, twice. Her true suicide was slow; she embalmed herself with alcohol. Suffering a portal hemorrhage, she spurted enough blood to overflow pots and pans. She lay in the hospital, her days numbered. Burgess makes a great show of guilt over her demise (his Catholicism comes in handy), but you can almost feel his relief at not having to march uphill with this wizened monkey on his back, mocking him. After her death he remarried, and discovered that he had a son.

Personal upheaval takes a backseat as Burgess shows us how he cobbled his books. He explains their themes, with this huge wad of gum in his mouth. "The solipsism suggested in The Doctor Is Sick—the external world can be confirmed only by one perceiving mind, even if it is deranged, but what do we mean by derangement?—is a tenable metaphysical position, but I was, am, no metaphysician." "Twenty-five years ago, when [The Wanting Seed] was published, nobody was prepared to take seriously that anthropophagy might be a solution to world starvation, and that overpopulation might thus be proved its own solvent. After the disclosure of the cannibalism that kept alive the survivors of the Andes air crash, there was rather less scoffing. Those survivors were well-nourished by the softer portions of their dead companions, though terribly constipated." (Go easy on the garlic, okay?)

Every book had its echo. Some writers claim to ignore reviews. Not Burgess. He has his head in the mailbox. In You've Had Your Time, he leaflets the countryside with his clipping file. "Time said.. "Robert Gorham Davis in the Hudson Review said..." "Time was unkind ...but the New York Times said..." "The Times Literary Supplement said..." "Time kindly said..Along with all this radar sleet, he includes a lengthy flaying from Brigid Brophy, and a rude toot from Jonathan Raban. "Let me drive [the reception to my novel MF] out of my mind with the dismissal of Jonathan Raban in the New Statesman: 'It's too pygobranchitic: meaning, roughly, that it breathes heavily through its hinder parts. ' This is what British literary criticism had descended to." Burgess wasn't a man to take this sort of thing sitting down. From Tangier he sends one smart aleck a postcard of shitting camels with the greeting "Thinking of you here."

You can see Burgess applying the popular touch with both thumbs, while trying to improve everyone's vocabulary. He spreads caviar over Spam.

It hasn't been all slings and arrows. Gore Vidal called him the most interesting English writer of the last half-century. But the suspicion remains that, although he possesses all the ingredients of greatness, Burgess has somehow made a flea circus of himself, frittered away the main chance. In his upcoming memoirs, Kingsley Amis ascribes Burgess's mammoth output to "a deep inner solitariness," which enables him to bear down but also prevents other people from impinging upon him. He's a library unto himself. "Nothing could be more characteristic of him than that there should be some sort of linguistic crux about his name, nor that he should go on to write that 'Anthony Burgess' shows 'the carapace of my nominal shrimp, the head and tail I pull off to disclose the soft edible body'—God knows what that last phrase refers to." Many of his novels are intricate stunts, wordplay devices that call shiny attention to themselves. Others are outright thumping naked cardboard lunges at best-sellerdom. For example, his recent Any Old Iron could have been written by a team of monkeys in Michael Korda's typing pool. "So: he wanted to see Zip; he seemed to be in love with Zip. Why was he in love with Zip?" (He also throws in some Hegel, just to cover himself.)

Best-sellers, of course, mean big cash. When his friend Shirley Conran nabs a million dollars for Lace, Burgess mutters, "Who wants literature anyway?" He tries to console his checkbook. "There was not much point in envying the rich writers of America, Saul Bellow and Norman Mailer for instance, since all their money went into alimony." But he always seems to have get-rich-quick projects going. He bats out a James Bond script in which Bond's twin brother is 008. He writes crapola mini-series and biblical epics. Using his prestige to hustle product has opened Burgess up to charges of being a highbrow for hire— Eurotrash's cultural attache. This seems excessive. He prides himself, rightly, on being a pro, whether he's pondering evil for a fish-and-chips tabloid or abridging Finnegans Wake. He isn't interested in being an artist-priest.

Burgess refuses to wear a restrictive collar. "Evelyn Waugh had never quite understood that Augustan elegance cannot work in the novel, " he chastises. Burgess has no time for Tories, for traditional understaters. He distrusts the clerical cut of T. S. Eliot. "I had always had grave doubts about Eliot's taste and, indeed, intelligence. He was supposed to have preferred My Fair Lady to Pygmalion. .." This from a man who in 99 Novels nominated Erica Jong's How to Save Your Own Life and Herman Wouk's The Caine Mutiny as being among the best fiction since 1939! What's your point, Jim? My point is that Burgess has high aspirations and hack instincts. The two don't go, at least not with him. There's an overlapping slop to his sensibility. He's too polyglot to be plain, too motley to be pedigreed. His most imagined novel, A Clockwork Orange, escapes highmiddle-low categorization. The earlier Enderby has a deeply felt funk. But in much of the rest you can see him applying the popular touch with both thumbs, while trying to improve everyone's vocabulary. He spreads caviar over Spam.

Yet through it all Burgess has been on literature's side. He ranks among modernism's last crusaders. The next century's job will be to wade through his millions of words to fish out a classic or two, if any. He has pumped all he can pump. "I have done my best," he writes at the end of You've Had Your Time, "and no one can do more." Daylight come, and he wanna go home.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now