Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSPIKE'S PEAK

GERRI HIRSHEY

Maverick director Spike Lee is at it again, and his new movie tackles the Big Taboo

Movies

High on a frigid hill in Harlem, director Spike Lee is shooting mouths: black mouths, gossipy mouths, grinning,

clucking, leering mouths. They are stationed around the playground in St. Nicholas Park this moonless late-fall night. It's dark and windy; the actors shiver as they run through their lines. Lee, a slight, bespectacled figure in a baseball hat, a tan parka, and chunky Timberland shoes, throws a huge shadow. He is backlit by a pair of five-story lighting cranes that rise from flatbed trucks. A sizable diamond flashes on his left ear. His voice is surprisingly big as he yells, "Action!"

The mouths begin:

"He's BLACK!"

"She's WHITE!"

"Lawd have mercy."

Lee is shaking his head.

"Cut. Turn it up a little. Remember, the brother is bonin' a white woman."

"HEAVEN FORBID!"

As the order is given to cut and print, a neighborhood drama has erupted just down the hill on 128th Street. A woman is screaming, trying to get away from a man who she says is menacing her. She is waving a crumpled paper she claims to be a court order of protection. Her supporters are pouring out of a vestibule and into the street. Six police cars howl

up. As the blue uniforms wade into the fracas, a gold-accessorized Jeep Cherokee rolls past on St. Nicholas Place, megawatt sound system shaking down the thunder: "WE GOT TO PRAY JUST TO

MAKE IT TODAY.

Production halts until the sirens die down and the rumble of M.C. Hammer fades with the Cherokee's taillights.

"This ain't Hollywood," says a corner sage in a Raiders cap. "This is fuckin' Homey wood. When my homeboy Spike wants action, he won't have to look far."

Homey wood is a lively spot. And despite the talent in heated trailers, the $2,500-a-day Louma crane angled out over the men's urinal in the park, the conga line of star-struck kids along the fence, life does not stop for art here. Love and sex and death and drugs work a mighty twenty-four-hour push and pull uptown, and all those elements move the plot of Lee's latest film. Jungle Fever. It features interracial sex, ItalianAmerican bigots, black, white, and brown crackheads, forbidden love, and murderous hate. Lee says it had to be shot in Bensonhurst, Little Italy,

and up here in chilly Harlem.

"Lawd have mercy."

The mouths have resumed. These talking heads are being shot for one of Lee's signature segments: the Mouth Montage. It's a close-up, quick-cut device he has used in three of his five films to burlesque racial and sexual stereotypes and it works well as funny, low-budget leavening. Economy was the reason he used it first (and most hilariously) in his debut sex comedy, She's Gotta Have It, shot for $175,000 in Brooklyn. Male suitors labeled "Dogs, #1—12" mouthed bogus come-ons to women, about their B.A.'s, BMWs, and other very personal assets:

"Girl, I got plenty of what you need. Ten throbbing inches of U.S.D.A. government-inspected prime-cut Grade A TUBE STEAK !!! " School Daze, Lee's film about life at a black college, featured a parade of coeds rejecting Lee's loser frat pledge, Half Pint. In Do the Right Thing, black, Italian, Korean, and Puerto Rican mouths performed a chorus of racial slurs. Now, in what will be the trailer for Jungle Fever, the talk is about interracial sex, and the mouths are nasty indeed:

Black man: "How's she look? She got a butt? No? A flat, WHITE butt?"

White woman: "How big is his. . .no way."

FEAR OF THE BIG BLACK DICK

yths on sexuality have really gotten people messed up—on both sides." Having finished shooting Fever, Spike Lee is discussing its future in the lounge of his Brooklyn headquarters. Forty Acres and a Mule Filmworks is housed in a smartly renovated firehouse across from Brooklyn Hospital in the Fort Greene section. Lee is sipping strong tea, watching a snowstorm blanket Fort Greene Park. Postproduction always comes in winter for him, and he likes it. It's a crazed but cozy time when he can walk the few blocks from his home to sit here at the editing boards and think about what he's got in the can.

Is there love in there, amid those sexual myths? There didn't seem to be much love in the Fever screenplay— in the dialogue (Continued on page 80) (Continued from page 70) or between the lines.

"Love has nothing to do with it," Lee says flatly. "For white women it's this whole sexual myth of the black man. And for black men it's been pounded in since the time they could think that the white woman is the epitome of beauty. So a lot of black men have this craving for white women."

Jungle fever. It makes everybody sweat.

"It is the big taboo, interracial sex," he says. "But it's been happening ever since black people were dragged kicking and screaming from Africa."

Why tackle the Big One, then?

And why now?

Lee smiles through the steam curling out of his cardboard cup.

He adjusts his hat du jour, a widebrimmed black felt number. "I don't think that Do the Right Thing or Driving Miss Daisy have left the subject of racism exhausted." He says he did Mo' Better Blues, his jazz romance, as a conscious break from the racism theme that made Do the Right Thing such a hot issue for him in the summer of '89. Whatever happens with Fever, he figures it can't be as bad as the astonishing and needless hysteria that ensued when a handful of white writers fretted about possible race riots before Do the Right Thing opened.

Lee says he's braced for the possibility of another jive media storm when this one opens in early June. Of course, he's thought about how the mouths will react to Jungle Fever: Critic Mouths, Nervous White Media Mouths, Certain Ethnic Mouths. Lee is chuckling. Oh, they're gonna hate this one, all those shots of a big, very blue-black man straddling a small white woman.

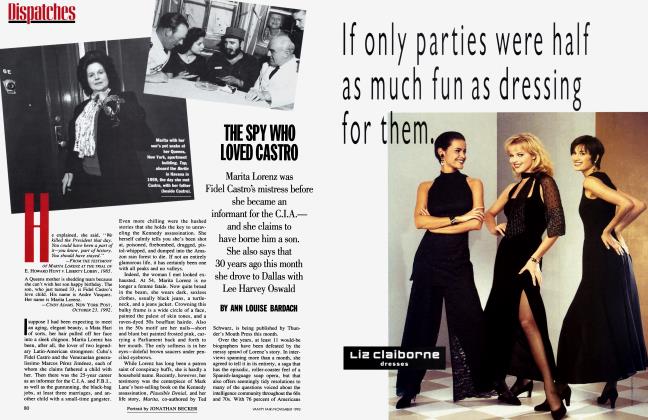

Wesley Snipes, late of New Jack City, plays Flipper, a successful black architect who falls for his secretary, Angie (Annabella Sciorra), an Italian-American from Bensonhurst. And sure, Lee figures, some Italians will go bullshit. Never mind that Martin Scorsese's very Italian parents liked Jungle Fever enough to appear in bit parts. The Bensonhurst paesans are drawn in, shall we say, broad strokes. They don't capisce the attraction between Angie and the "moulan yan." When her father finds out about it, he beats her savagely.

"We're not making anything up," says Lee, citing the ugly neighborhood furor in the wake of the Yusuf Hawkins murder in Bensonhurst in the summer of '89. There, an innocent black man was murdered by a white mob a block from the home of a woman suspected of dating another black man. Put Lee's 35mm. reels next to real news footage of Bensonhurst citizens holding up watermelons and yelling "Niggers go home!" and he has a point: the racial climate in New York is stranger than fiction.

Nothing new, nothing Live at Five about that, Lee reminds. Wasn't the K.K.K. formed to protect southern womanhood? Isn't that how thousands of black men got lynched? "It's no coin-

"Spike likes to fight," says a friend. "There's a gleeful look he gets...when shit is being stirred up."

cidence that many of those black men who were lynched were also castrated," he says. "Yusuf Hawkins, I saw that murder as a lynching, too."

Lee is smiling again, looking almost mischievous. "You could say that the subtitle of Jungle Fever could be Fear of the Big Black Dick." The soft voice breaks into a harsh, startling laugh.

BROTHER, CAN YOU SPARE A QUARTER?

pike likes to fight," says writer Nelson George, a friend and an original investor in She's Gotta Have It. "There's a gleeful look he gets, a certain kind of excitement in his eyes, when shit is being stirred up."

Indeed, Lee is almost merry this morning. He says he has been up since 6:30, revising the screenplay for his next film, a big-budget epic on the life of Malcolm X for Warner Bros. He'll work here editing into the night with his talented, loyal, and nearly all-black staff. If it's very late, his best friend and vice president, Monty Ross, will probably give him a lift home; this child of the subways has never learned to drive.

Ross, who does everything from fielding huge endorsement offers to taking out the trash, says, "We don't have the real corporate attitude. What we're doing here is very family-oriented." Lee's immediate family is very much involved. His father, Bill, a jazz musician, has composed music for all his son's films. Sister Joie and brother Cinque act in them; brother David is the unit photographer.

Forty Acres is also a neighborhood thing, built with local labor, and the native son keeps buying buildings here to house his retail store, his production office, his equipment. Lee's great-grandfather, a student of Booker T. Washington, had a saying: "Cast down your buckets where you are." Which meant: If you make it, go back home and haul the rest up with you.

These days, the buckets are full of cash, and the mouths have been asking: "Is Spike Lee exploiting his own people? Is he committing gel-sole genocide by selling all those Air Jordans to ghetto kids?" Lee has responded angrily to his critics. "I find it fucking amazing that the minute black people start a business you get asked all these fucking stupid questions," he told reporters at the opening of his retail store. "When Robert De Niro opened up Tribeca Grill," Lee notes, "nobody asked him anything like that." Lee will not discuss his charitable contributions, but he has quietly plowed some of his profits back into the black community. He has given money to start a scholarship fund at his alma mater, Morehouse College, to Mother Hale's home for the babies of drug-addicted parents, and to other community efforts.

And as he antes up, as he solidifies his own investments, the offers keep coming. Would Lee consider directing a film of Parting the Waters, Taylor Branch's best-selling biography of Martin Luther King Jr.? A Burger King campaign? (It was no thanks to both.) As he sits talking, his slim fingers worry the binder rings of his Day Runner datebook. His days are divided into fifteenminute segments and he has inked in every one. He is only thirty-four, and in a very big hurry.

In 1990-91, he will have made two feature films, produced two related books, overseen two sound-track albums. He has expanded the line of Spike Lee clothing, videos, and film memorabilia in Spike's Joint, his retail store; signed his own record-production deal with "that big gorilla" Sony; shot a short feature on Mike Tyson for HBO that won two sports Emmys; and directed three music videos and nineteen commercials in multimillion-dollar TV campaigns for Levi Strauss, Nike, and Diet Coke. He lectures, heads a film workshop at Long Island University, and in the spring of '92 he will be teaching a course on film at Harvard. This September he will also begin shooting the Malcolm X film with Oscar winner Denzel Washington cast in the title role. He's building a vacation home in the Farm Neck section of Martha's Vineyard, a spot long favored by black professionals. He just doesn't know when he'll have time to go there. There's also little space in that Day Runner for romance.

Asked about gossip-column reports on his relationship with model/actress Veronica Webb, Lee will only say, "I see a lot of people. The last girlfriend I had broke my heart and I made a vow I'd devote myself completely to cinema. Forever. AHH A-HA-H A A A AA. ' '

Fame hasn't changed his life-style much, but now he pays for his deli takeout with an inchthick roll of hundreds and fifties. Why is it, then, that rich, powerful Spike Lee finds himself cadging quarters off friends?

Because of his mouth. Given his big, opinionated, African-American mouth, Lee will not say important things on his own phones. He can't prove it, but he thinks they're bugged, like those of other Troublesome American Negroes. (Eddie Murphy told Lee that bugs were found in his L.A. mansion, a place that receives the likes of Jesse Jackson and Louis Farrakhan. Eddie found one in his bedroom. . .)

"If people write articles saying I'm the author of a film that's going to make 30 million African-Americans raise hell, you know for sure that the F.B.I. says, 'Hey, keep tabs on him,' " Lee reasons. He just had his home and office swept electronically and they found nothing— "this time." No matter. He's switched to pay phones for the funkier conversations. Pretty soon he'll have stretchedout pockets like all the busy mafiosi who have to transact business with a pantload of quarters.

He laughs again, fortissimo. "I'll be like John Gotti," he says.

IS YOUR SHIT CORRECT?

1% aranoid, or prudent? The mouths WF may well be after Spike Lee. But he I has been a willing, almost cheerful provocateur. When Do the Right Thing lost to sex, lies, and videotape at the

Cannes festival, Lee groused about another predictable victory by "a golden white boy." Of New York Times critic Janet Maslin he sniped, "I bet she can't even dance, does she have rhythm?" He says he signed his own record deal because black radio is not worth listening to ("Their playlist is so ignorant").

Lee's standards of Correct Blackness have also censured Whoopi Goldberg for her blue contact lenses, Michael Jackson for his nose job. Lee has said of Jackson, Quincy Jones, and Prince, "They aren't regular black people." On Eddie Murphy: "I think that he's not really utilized his clout effectively in getting jobs for qualified African-Americans. We went over this again and again and again."

Ask around his neighborhood in Fort Greene and they say, "Thank God for Spike Lee." Ask around the Industry, the press, and the mouths are a tad snappish. Spike the rhetoric, say the headlines. The man is ready for a takedown. He's been attacked by white critics: "Lee the political activist. . .is becoming a bit of a joke" (Walter Kim, GQ). A black columnist damned him as an Afro-fascist. "Intellectually, [Lee] is like John Wayne Gacy in his clown suit, entertaining those who cannot believe the bodies buried under his house" (Stanley Crouch, The Village Voice).

Review the litany with Lee, suggest that there are many who would like to see him fail, particularly with the huge and heavily freighted Malcolm X project, and he nods. "What you just said is true. But that hasn't made me hesitant one bit. I'm not scared. We don't intend to drop the ball."

In some areas he has lightened up. He insists he's now "cool" with Whoopi,

with Eddie. At the last moment he cut Fever's opening sequence, which featured the director ascending into the sky on a camera crane, holding forth on race relations. He even takes a shot at fashionable Afro-hubris when Snipes's character protests, a little too vehemently, that despite his two-tone love life, "I'm still pro-black. My shit is correct. ' '

It's a problem, Lee admits, keeping his artistic and Afrocentric agenda correct and his budgets rising. He has demanded and received total creative control on all five of his films. But none has cost more than $14 million. "I couldn't make a Havana," he says. "They wouldn't let me make a $ 15-million-plus movie and still retain the same control. They'll let me do what I want as long as it's a price they can live with. ' ' And if the studios get skittish, another front of white corporate America is there to bankroll Forty Acres. Advertisers may not buy Lee's polemics, but they are falling over themselves to buy what Hollywood has taken to calling the "awareness" factor. The Mouth is mondo in the national brainpan. Levi Strauss found that just Lee's voice asking questions off-camera was sufficient ID in their button-fly-jean ads. In 1991, nobody doesn't know Spike Lee.

SCHMOOZE CONTROL

T his past summer, Robert De Niro and I Toukie Smith invited their friend I Spike Lee to a very casual Sunday lunch at their home in the hills above Los Angeles. The party was in the backyard, where lawn chairs accommodated the power rumps of Mike Ovitz, Sean Penn, and Penny Marshall. They were gathered around director Richard Brooks's wheelchair, drinking in tales of fifties Hollywood and chomping Ms. Toukie's piquant short ribs. When Lee arrived in the company of Monty Ross, he perched a good distance from the bankable epicenter. "Hey, Spike," yelled Sammy Cahn's wife, Tita, "come on and join the party."

Ross says that people in Tinseltown are always telling them to loosen up: "They're like 'Come on, guys, don't you ever take a break? Relax, enjoy the sunshine.' "

Ross and line producer Jon Kilik accompany Lee on pitch meetings with Universal and they concur: Spike is not big on schmooze. "I don't think he has the time to waste," says Kilik. "If you want to do it [his movie], fine. Why sit around having lunch or dinner? Let's shake hands and I'll go make the film and see you on opening day."

David Puttnam, the first major studio head to sign Lee, says that he and his Columbia Pictures lieutenant David Picker were willing to fly to New York to meet with Lee. They had seen She's Gotta Have It, and they had a plan. "What David and I had in mind was to try to repeat what David had done years ago with Woody Allen," says Puttnam. "Which is to come in behind someone who wanted a career and be prepared to go through thick and thin."

Unfortunately, they experienced only the latter: Puttnam was abruptly replaced by Dawn Steel before the release of School Daze, and the film itself took a critical pounding. Turkey or not, it was one of Columbia's few money-makers that year. Lee, Picker, and Puttnam have remained friends—despite Puttnam's use of the one bedeviling analogy that turns Spike Lee apoplectic: "that tired old bullshit black-Woody Allen thing."

O.K., he's a short, Brooklyn-raised writer/actor/director who makes small, idiosyncratic, ethnocentric films, wears wire-rim glasses, doesn't drive, and finishes a film every fall. Yes, he often plays a schlemiel who gets gorgeous women. O.K. But what else was David Puttnam buying?

"I think he has extraordinary onscreen vitality," says Puttnam. "I think his performances are very good—he's gotten performances out of people I know for sure are not great actors. He's got a strong visual sense. He's a very competent all-round director."

"We want to be in business with Spike," says Tom Pollock, head of Universal Pictures, which has bankrolled Lee's last three films. "He makes good movies, and if they're done inexpensively, they're profitable. I'm not looking for Spike to do Home Alone. When you make movies with Spike you aren't going for the home run."

One reason Pollock feels Lee's films hold at first or second: Spike Lee is not partial to happy endings. Most of his work ends ambiguously, on a question mark, or, as in Jungle Fever, on a sin-

gle, anguished howl. "That's why there may be price limits on what he can do," Pollock says. "By and large, people go to the movies to escape from their trouble, get into stories, mythologies, reassurance. That's not what Spike Lee is about. ' '

But he's only just begun. "I don't think of him as a defined talent yet," says Puttnam. "To judge it all now is rather like thinking Woody had defined himself with Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex." Lee, he

Lee says he still dreams about his mother, vividly. On waking, he's said, "I could feel her there."

says, is still exploring the medium. Yes, like Woody. "I mean, I don't feel that Spike has yet made his Annie Hall."

HOORAY FOR HOMEYWOOD

A hil's big mike is waggling, the silver WF thatch bounces as he scampers down I the aisle. "Well, I'll tell ya what," he says, "Hollywood's NEVER GONNA

BE THE SAME!"

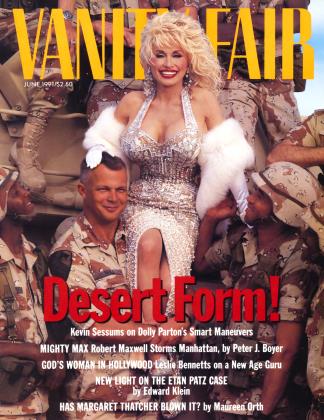

They've made it, they're a trend, they're a Donahue, by God. Young black filmmakers, all in a row. Sitting on the NBC soundstage, they're a study in the smart eclecticism of black male style. On the right, Reginald and Warrington Hudlin, Harvard and Yale, sweatered and urbane, director and producer of House Party!, a surprise hit of '90. At center, the charming, G0-handsome Mario Van Peebles, director/actor of Current Controversial Hit New Jack City, the reason we are all here today. And on the left, in sneakers, jeans, and his red "Fever" cap, slumped over, staring at the floor, is Spike Lee. Their faces and their work could not be more diverse, but today they are all "black film."

You don't think something's going on here, folks? Phil's got graphics, Phil's got stats. Thirteen black-directed or -produced films have been made in 1990-91—more than in the entire previous decade! And look at these profit margins: the Hudlins' House Party! cost $2.5 million and brought in $26.3. Spike's Do the Right Thing cost $6.5

million and yielded $28. And New Jack City is running second only to The Silence of the Lambs—on far fewer screens, mind—and it's killing.

Yes, gentlemen, killing. New Jack City is about black drug gangsters, its message anti-drug. It's had huge box office—$10 million the first week. And riots outside some theaters. A death in Brooklyn. Waggle, waggle, WOULD YOU LET YOUR CHILDREN GO?

It's a bum rap, the young men counter. The theater in L.A. was greedily oversold. If there are rival gang members in a theater, they'll shoot one another if Mary Poppins is on the screen. A kid was murdered during a showing of Godfather III on Long Island. Did theaters threaten to quit showing that gangster flick as they have New Jack! Did they blame Coppola?

Finally, Spike speaks. This alarmist media hype is a problem for all of them. As soon as the New Jack flap began, exhibitors started calling Tom Pollock at Universal, saying they don't want to book Jungle Fever sight unseen. Could it be another long, hot Spike Lee summer for the Universal P.R. machine?

There is a ghostly phone call from Mario's father, Melvin Van Peebles, who says that he considers all these fine young men his sons. Twenty years ago, Van Peebles made the black classic they all look up to, Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song. In 1971, the filmmaker received death threats. Only two theaters in the whole country would book it at first. Eight hundred sixty screens for New Jack ain't Schwarzenegger, but it's better. Van Peebles the younger looks over to Spike Lee, claps him on the back, and says, "We owe a LOT to this cat here." The cat manages a smile at the floor. Phil calls for them to cue up the trailer for Jungle Fever, eyeballs the audience matrons, and hollers, "HERE'S RACISM COMIN' RIGHT AT YOUR FACE.'"

IS IT THE SHOES? IS IT THE SHOES?

It the center of all the noise, there is a good deal of quiet. Talking with Lee can take some getting used to, owing mainly to the clots of silence. Wesley Snipes says that sometimes it takes so long to get a response that he's conclud? ed that Lee is in "extended play," the slowest VCR setting: "You know how you get a reaction from a person if you're telling them something? Spike will be deadpan. Maybe he just analyzes the hell out of it and he'll answer two and a half minutes later. ' '

"He isn't being rude," his grandmother Zimmie Shelton insists. "Spikey will tell you what he wants you to know and you have to accept that." He just doesn't talk much. Never did. But this can become a knotty problem for a person many consider an ad hoc spokesperson for his race. "So many people are offended by Spike because people—especially black people— want Spike to be Jesse Jackson, gregarious, give them that eye contact, the firm handshake," says Nelson George.

"He's just not like that. He internalizes everything."

Even the external Spike is an off-the-rack cipher. He dresses in endless combinations of athletic shirts, sweats, jeans, sneakers. Often he wears his own promotional items—Forty Acres caps, Do the Right Thing jackets. His only serious fetish is a hat collection: a prized Brooklyn Dodgers cap, fedoras, porkpies. As guest editor of Spin magazine, he posed for a feature, "Spike Lee's All-Star B-Boy Caps." Baseball caps, as the text explained, are the sine qua non of b-boy cool.

Lee's b-boy character Mars Blackmon is his most popular creation, one that has kids dogging Spike on the D train, at ball games, yelling, "Please, baby, please, baby, please, baby, baby, baby, please." Bicycle messenger Mars has had two lives, as Nola Darling's ain'ttoo-proud-to-beg suitor in She's Gotta Have It, and now as Michael Jordan's geekazoid sidekick in those singular ads for Nike. Mugging inches from the camera, chattering like a magpie on speed ("Is it the SHOES? Is it the SHOES?"), Mars is a quiet man's nightmare. Even his look is loud, the gold MARS necklace hanging around his neck like a license plate, the boxy Cazal glasses. The only thing Spike and Mars seem to have in common is Jordan-worship and the b-boy threads.

"Spike has a merchandising eye," says Ruth Carter, his costume designer. "An eye on what will be happening in the street." He knows, for instance, that these days b-boys are wearing Timberland hiking shoes and not sneakers. For Jungle Fever, Carter took him to a Timberland store and fitted out his five-footsix-inch, 125-pound frame: 36 jacket, 30 waist. Always, she has to take up the cuffs and sleeves; if Spike's fashion savvy is off-the-rack, his body isn't. This being the case, homeboy haberdashery can have a comic effect; athletic socks droop around skinny ankles, baggy shorts flap around his thighs.

Is it b-boy, or is it burlesque? There is a certain duality at the heart of what we

might call the Spike Lee mystique. He's a fan of modem dance and the Hoyas, "an art snob," says a friend, and a boy from the 'hood. He can seem painfully shy, but will take his clothes off onscreen. He goes nowhere without a hat, but will shave his head for a movie. He's quiet, but wearing his director's hat he's not afraid to pump up the volume. "I wouldn't say he's a madman," says Ruth Carter. "But he's tough. You don't want to do the wrong thing." Screw up, says Carter, and the Quiet Man will be in your face. "Your HAIR will be blowing back."

Ask Lee's best friend, Monty Ross, about the contradictions and he says it's an illusion. A head that swivels all the time can seem like it has two faces.

Say what?

"I mean, it'll happen if you've come up always watching your back."

MAMA, I LOST MYSELF

T he Dodgers had just one season left I in Brooklyn when Shelton Jackson I Lee arrived in 1957, a small, feisty baby bom on the cusp of integration. That year, Congress passed the first voting-rights legislation since Reconstruction. The fall that Jacquelyn Lee, a teacher, escorted her son to kindergarten, it took three thousand troops to get James Meredith registered at the University of Mississippi. Every summer, Bill Lee, a jazz bassist, drove his family south to Alabama or Georgia to visit each set of grandparents. In time there were five children, four boys and a girl. The car trips were hell, but the kids needed to know where they came from. Theirs were not ordinary folk.

Bill Lee's grandfather William James Edwards was bom in Snow Hill, Alabama, and, despite poverty and a crippling bone disease, attended Tuskegee Institute. In 1893, he founded what became the Snow Hill Institute to educate black youth. Nearly half a century later, Bill Lee would work his way to Atlanta's Morehouse College at a sawmill. When he arrived as a freshman, Martin Luther King Jr. was a senior there. Money was always tight, and in 1951, Lee began taking his Sunday meals at the home of a pretty, lively girl from Morehouse's sister school, Spelman. He got only six days' worth of meals as a boarder, and Jacquelyn Shelton's mother, Zimmie, knew how to feed a man.

Mrs. Shelton had gone to Spelman as well, and graduated with a teaching degree. She was brought up a strict Baptist, a polite, religious woman who was determined to see her only child come up the same way—with dignity. When Jackie was a girl, her mother would sit at her kitchen table applying a thin brown wash of watercolor to the faces of children on the greeting cards she bought. Cards, books, dolls, "they were all white," Mrs. Shelton says now. "I wanted more than that."

Her husband, Richard, had always wanted to teach French. He graduated Morehouse with a degree in French and spoke fluently, but the realities of forties Atlanta landed him in the post office. Knowing that big things were still out of reach, Zimmie Shelton began with the small ones. "I insisted on my daughter having black dolls." She laughs, says the early ones were plug ugly, if you could find them at all.

All her grandchildren call her Mama. Since Jacquelyn Lee died of cancer in 1976, Mama has been Spike's rock. (His father married Susan Kaplan, a white woman he'd met in a club, a few years after Jacquelyn's death.) It was Mama who got Spike through the lean times. On the credits for his acclaimed student film, Joe's Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads, Zimmie Shelton was 5 listed as producer. When he ran out of | money trying to make Joe's and She's R Gotta Have It, again and again, he called Mama, who always managed a money order. During the controversy around Do the Right Thing, when he lost it during an early TV appearance, just went silent for a few agonizing moments, he got on the phone and confessed to the One Who Really Loves Him.

"Mama," he said, "I just lost myself."

Zimmie Shelton is eighty-four now. She still lives in Atlanta and is not much for traveling. She did make it to one of Lee's premieres once—she's not too sure which. Talking about her firstborn grandchild, she admits that no one was as surprised as she's been that Spikey was the one to become a big star. He was just too quiet. Jacquelyn nicknamed him Spike because he was a tough little baby. But sometimes Mrs. Shelton felt her daughter kept the child too close for his own good. "I used to tell her, 'Let Spikey go, he's just a little kid now.' She'd just gotten married and he was her companion."

All told, Lee's childhood was blessedly normal—a fact that seems to vex those looking for a grimmer ghetto pedigree. Pressed by People magazine, his sister, Joie, allowed that "there were lots of times when the phone was cut off.. .and we had meager servings for dinner." But despite the occasional belttightening that a musician's family must endure, Lee's bio does not match the standard homeboy press kit. Three of the five children attended private school. Lee's parents owned their house; the family car was a Citroen station wagon. Every year, the family motored to the Newport festivals, where Bill Lee accompanied artists such as Odetta, Peter, Paul and Mary, and Judy Collins.

But if Spike Lee grew up privileged, it had little to do with money or real estate. "The fellas in the neighborhood thought he was better off just because he had two parents," says Monty Ross. "If you had a father, oh, man, that's powerful stuff. Or even a man around."

He also had history from all those trips down South. "Spike was always real tight with his family," says Ross. "The men really stick together, take care of business. To know your lines, those generations—to have history .. .that's a very powerful thing."

Sometimes, the history lessons were irksome, Lee remembers. "I was forced to read—Langston Hughes, that kind of stuff. And I'm glad my mother made me do that. Of course, I couldn't see it at the time."

Once Spike left for Morehouse, Jacquelyn Lee wrote him long and frequent letters. When Spike wrote back, she returned his letters, corrected in red Magic Marker. She died of liver cancer, quite suddenly, in October of his sophomore year. Lee kept her letters, and reads them whenever he feels the need. He says he still dreams about her, vividly. On waking, he's told his grandmother, "Mama, I could feel her there."

"So, Spike's an asshole," Rosie Perez sums up.

"He is a FUCKIN'ASSHOLE. But he has a big heart."

The year he lost his mother, Lee met Monty Ross at Morehouse. He was, remembers Ross, "kind of morbid." The boys started dragging him out, to cruise the Fox Hunt, an Atlanta bar, and to the movies—always the movies.

FEVER

A ne stormy Atlanta night, Spike Lee 11 went to see The Deer Hunter with W his friend John Wilson and some other Morehouse students. It was their junior year. As they packed into a cab for the ride back to campus, Lee turned to Wilson and said, "John, I know what I want to do. I want to make films."

It wasn't just Michael Cimino's film that convinced him. Lee went to the movies all the time, was partial to Bertolucci, Scorsese, Kurosawa. Wilson, who is now an administrator at M.I.T. and teaches at Harvard, reminded his friend that if he was going to make films they would have to speak to black Americans. "You can't just ape Hollywood," Wilson said, and of course his friend agreed. From then on, says Wilson, "Spike was a monomaniac with a mission."

With Monty Ross, he made student films, went to every movie he could. "The thirst was so heavy," Ross recalls. "People knew we would do anything short of robbing a bank to become successful. We were crazed, and we knew it."

Night after night the two turned up at Mama's kitchen table with empty stomachs and big ideas. Lee was always scribbling in notebooks—his grandmother still has some—making plans for storming the studio gates. "Spike didn't just want to get in the door of the house," says John Wilson. "He wanted to get in, rearrange the furniture—then go back and publicize the password."

"Fever," says cinematographer Ernest Dickerson, who first collaborated with Lee when they were students at N.Y.U.'s film school. "We all had it bad. We were on a mission. We wanted to make films that captured the black experience in this country. Films about what we knew. We just couldn't wait."

Now Dickerson's vibrant, painterly work in all Lee's films has made him much sought-after. But early on, making a little look like a lot was Dickerson's greatest contribution to the Spike Lee oeuvre. As they made those first student films together there were others like them elsewhere, working, beginning: Charles Burnett, James Bond III, Robert Townsend, Euzhan Palcy, Charles Lane. In 1979, Warrington Hudlin helped found the Black Filmmaker Foundation. They drove up to Harlem in a truck, hung sheets on tenement walls, and showed black films in the streets. Lee had a "screening" of his student film The Answer at Leviticus, a black dance club in midtown. He called it guerrilla filmmaking, and it was the only way.

SHOOT THE MESSENGER

A ften, men who cohabitate with lovely 11 dreams must do so in relative squaW lor, and Spike Lee was no exception. He had long since left the family home, where his father lived with his second wife, and his basement apartment was a gloomy cave of ambition. Two summers after graduating from N.Y.U., he felt he had a movie to make, and it was dark as well. He called it The Messenger.

"The plot is about a young man, a bike messenger," says Lee. He is somewhat vague about it, he says, because the whole experience was so painful. Others have suggested that the story was uncomfortably autobiographical. The messenger has three or four brothers and a sister and a mother he loves. She drops dead of a heart attack while shopping. A short time later, ' 'the father comes home with a white woman," Lee recalls. "Then it's the whole turmoil in the family, the reaction."

A friend who read the screenplay says it ends with the messenger driving the white woman off—violently. It was angry, ugly, and ultimately too expensive. "We were in pre-production the entire summer of 1984, waiting on this money to come, and it never did," Lee says. They hung on all summer, "then, finally, I pulled the plug. I let a lot of people down, crew members and actors that turned down work. I wasn't the most popular person. We were devastated."

Lee says he moped—for only a week. "I saw I'd made the classic mistakes of a young filmmaker, to be overambitious, do something beyond my means and capabilities. Going through the fire just made me more hungry, more determined that I couldn't fail again."

He sat down to write a script that would take place in just one location, with just a few characters—something that could be done on a minuscule budget. It would be a comedy. He'd keep his bike messenger and make him a hiphop Puck: Mars. He was ready. But first he had to know a little bit more about women.

ARE ALL MEN DOGS?

A pike Lee has long had problems with %his women. He calls it "a weaker ness" in his work. Critics point to the lack of dimension in his female characters. And in Lee's own coffee-table book, Five for Five,due out this month, novelist Toni Cade Bambara scolds him for backward sexual politics in School Daze.

It's not that he hasn't tried, he says. As he began writing She's Gotta Have It, he dutifully declared in his film diary, "I also need to read as much black women's literature as possible... "

He read his Toni Morrison, his Zora Neale Hurston. But he spent more of those pre-production days asking thirty or so women some very personal questions. His leading lady would be a "freak" for sex and he wondered—professionally, of course—just what women liked. Four years before Steven Soderbergh made sex, lies, and videotape, Lee began taping women's responses to questions like:

When you gotta have it, how do you get it? Does penis size matter?

He called it the A.S.S. report (Advanced Sexual Syndrome). He insisted on in-person interviews. Night after night, he played the tapes back. He sat on the bed, the only serious furniture in his cheapo room-with-a-kitchen apartment on Myrtle Avenue. The tapes wound on, female voices describing orgasms, threesomes, oral sex. Lines of dialogue flew onto his yellow legal pads. He especially liked the answers he got to one key question: Do you feel all men are basically dogs?

In a Spike Lee Joint, it's generally a junkyard battle for the dogs and dogettes. Call it the bone dialectic, a constant tug to get yours. Everybody's gotta have it, but who gets to keep it? In Mo'

If the leamsters give Lee any trouble on his next film, well, it's going to be a long hot Indian summer in Harlem.

Better Blues,two women tussled for Denzel Washington's trumpet player— who put his music first. In Fever,Flipper leaves his wife and child for the lure of the myth. In all of Spike Lee's movies, the men have landed on top, but he says the balance is shifting. "I know I've improved," he says testily. "It's in the films, so I don't have to explain how."

If there was a quantum leap, it came with Rosie Perez's portrayal of Tina in Do the Right Thing.She is the girlfriend of Lee's lazy pizza deliverer, Mookie. Tina is a Puerto Rican flower who bears Mookie's child and his indifference with shrieking, majestic rage. Lee originally conceived the role for a black actress. And Perez had no thoughts of becoming an actress, period. Bom in Brooklyn, she was a student in Los Angeles when Lee first encountered her there in March of 1988. He was writing the film, still doing promotion for School Daze,when he threw himself a birthday party at a dance club called Funky Reggae on La Cienega. That night, in Perez, he found a Mouth as formidable as his own. They describe their meeting, in a split-screen montage:

PAS DE EFFIN' DEUX

pike Lee: Yeah, we had a butt contest.

Rosie Perez: Oh, there were some BIG booties, MOUNT EVEREST booties. S.L.: This Puerto Rican girl was dancing on the speaker. R.P.: I thought it was degrading, so I was being loud and rude, yelling. A bodyguard pulled me down and I thought they were going to throw me out. Instead they put me up onstage with the band. Spike started dancing with me, I think to try to embarrass me, but I ended up turning him OUT!

S.L.: SHE'S OUT OF HER MIND!

R.P.: He tried to talk to me and I was rude to him.

S.L.: Right then and there I began to think about having Mookie's girlfriend

be Puerto Rican.

R.P.: He asked me to call him, but I didn't right away.

S.L.: We called and called and CALLED and finally she called us back.

[Finding they were both going to be in Washington, D.C., Lee arranged to give Perez a ride home to Brooklyn.]

R.P.: I was very nervous and he didn't hardly talk to me. And when he saw where I lived he started laughing. I thought he was being rude and I CURSED HIM OUT. Hegoes, "No, Rosie, THIS IS FATE."

S.L.: That five-hour trip I decided she was right for the part.

Perez had to walk only six blocks from her home to Lee's movie set in the heart of Bedford-Stuyvesant. She knew so many street people that the suited, bow-tied Fruit of Islam muscle hired to secure the set would not let her past. Five-foot-nothing Perez got in their stem Muslim faces: "Hey. HEY. I'M IN THE FUCKIN' MOVIE!"

More quietly, she explained some things to Spike. "I gotta show the girl's side," she told him. "I gotta show her frustration, I dunno." The continuous reel-to-reel between Lee's ears caught the voice of Very Real Rosie. When her scenes came up, Tina had changed in the script. She had Perez's thick-as-CocoLopez accent. And she had more rage. In the film, Tina fizzes and explodes down a hot, narrow tenement corridor like a shook-up can of malt liquor. She even uses some of Perez's personal homegirl bons mots: To the curb, Mookie. You can step off wit yer stupid-ass self.

When the movie opened, the street reaction told her that she had done her job right. "I had girls stop me on the street going, 'Yo, I felt it, I FELT you, 'cause my man's no good and I feel like telling him off but I love him. Girl, you played that shit to a 7V "

In Tina, Lee finally had a real woman. Her voice could make a cat jump, but it spoke of and to the forgotten moviegoer—that vaunted Lee mandate. "When we danced on that speaker," he admits, "it was a godsend."

Perez is still an actress in Los Angeles, currently working on Fox TV's In Living Color. She says she doesn't care if she ever works with Spike Lee again. "Workingwise," says Perez, "a lot of people found him not as warm as they needed a director to be, because he's such a workhorse. But the thing is—and this is like NO BULLSHIT, right?—if you're friends with him, and you ever need something, the man will be there."

They have stayed friends, even though Lee cast her for a featured part in Jungle Fever, then called her just as she was about to fly to New York to say he'd changed his mind. Recently, when she had a serious personal emergency, he was there for her, across three thousand miles, in a big way.

"So, Spike's an asshole," Perez sums up. "He is a fuckin' ASSHOLE. But he has a big heart—you know what I'm saying?"

And on the evolutionary chain?

"Much higher than a dog."

In Jungle Fever, Annabella Sciorra plays another leading lady from a tough neighborhood. The chemistry between Sciorra and her director was so explosive, so unpleasant, that she declined to be interviewed for this story. The problem, as the gentlemen involved describe it, was over the interpretation of her character. Lee, who insists he is very pleased with her performance, says, "Stuff like this is going to happen where there might be some yelling and screaming."

Wesley Snipes is more specific: "Annabella had a strong problem believing there were white women out there who looked at black men believing that they were.. .uh, well endowed. She's saying that's not really true. I say, HELLO. Wake up, Snow White."

Annabella, he says, didn't think her character was motivated by lust and curiosity, but by love and ambition (she's a secretary to Snipes's architect). So she wasn't buying into the stereotype? Snipes laughs. "Absolutely. No sale."

KISS MY ASS. TWO TIMES.

£ A omebody could definitely be killed X behind this movie. Hopefully, it W won't be me. AAAAAAAH-HA-HAHAAAA!"

By any means necessary, Malcolm X will be done, says Lee, who has taken on problems that two decades and several teams of studio talent could not conquer. Producer Marvin Worth acquired the rights from Malcolm X's widow in the late sixties; they have been owned by Warner since 1970. Of the several screenplays done, Lee has chosen one by James Baldwin and Arnold Perl as the basis for his version.

No, Lee says, he's not intimidated rewriting James Baldwin. Yes, he expects some strong reaction from the Nation of

"Somebody could definitely be killed behind this movie," says Lee. "Hopefully, it won't be me."

Islam, which ousted Malcolm, but as yet Minister Farrakhan has not returned his calls. Hell no, the Fruit of Islam won't be guarding this set. He is writing every early morning for four hours, and for once the Mouth is doing a lot of listening, interviewing Malcolm's brothers, his aides, William Kunstler. And he says he needs some long talks with one much-respected elder, Ossie Davis.

Davis and his wife, Ruby Dee, are the actors Lee calls on most often to represent the older black generation in his films. They were also good friends of Malcolm X. Davis says if asked, he will tell Spike Lee what he would like to see: "To me, what makes Malcolm Malcolm is not the rhetoric, not the fiery summons to battle. It's not even the call that blacks resume their manhood by any means necessary, NO. It is study, reading." By educating himself in prison, and afterward, Davis says, "Malcolm learned to understand the Man and the system that was his enemy. Having learned what racism was, he was wise enough to come up with a strategy for black survival. This was a man who remained a student all his life."

Davis knows that Spike is studying hard on Malcolm. And he's been watching Spike study on Hollywood, on business, camera specs, sound technology. "He investigates, he studies," says Davis. "He PLANS. Spike is a child of Malcolm."

Great planning has gone into making Malcolm X. And, once again, Lee is expecting big trouble even before the movie is shot. He says the New York Teamsters will not be working on Malcolm X, because of what he alleges is their long-standing refusal to hire blacks. Trying to make a big-budget film in Manhattan without the Teamsters is considered folly at best, but Lee has already stated his position on Donahue.

A few hours after that broadcast, Lee calls and reiterates his position. It's 9:30 and he's still in the office, signing checks and lining up his ducks for the next scuffle. Filming is set to begin on Malcolm X on September 9, and if the Teamsters give him any trouble, well, it's going to be a long hot Indian summer in Harlem. He has the big studio bankroll, he has Oscar-winning black talent, he has the burden of legend on his bony shoulders, but he will not give in. Finally, he's got to put the money where his famous Mouth is. He says he has no choice.

"How am I going to make Malcolm X, give a million and a half dollars to an organization that isn't even hiring black people?" he says. "Malcolm would turn over in his grave."

And if the union tries to halt production? "I can say we're not using you motherfuckers, and if you want to start some shit, we can start some, too."

Just what kind of shit? Legal?

"No. Rough stuff. Anybody that tries to fuck around Malcolm X, we're gonna have this thing so TIGHT."

Lee has drawn his line on the sidewalk. He's talking extra security, and he's talking 70-mm., political, mediaspread OUTRAGE. If you've been abused by it, you learn to use it, too. He's going to make this thing bigger than his trialsize self.

"It's not going to be like they're trying to stop Spike Lee. It's going to be an insult to every black person in America. That's how tight the shit is gonna be on this film."

He says he'll recruit Jesse Jackson! Louis Farrakhan! David Dinkins! Police Commissioner Lee Brown! He will make the Making of Malcolm a political issue. And if the Teamsters, who he says have refused to even meet with him, object? Threaten? Spike Lee, who says he has not known real fear since the dismal summer of The Messenger, has a special message for them:

"They can kiss my ass. TWO times." □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now