Sign In to Your Account

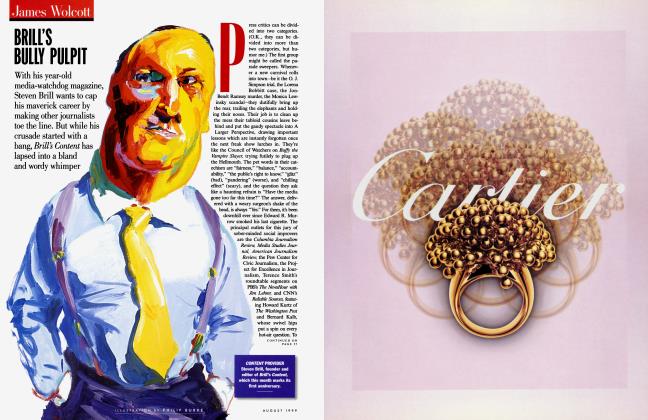

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLIPSTEIN’S LIP

Why the self-proclaimed whiz kid of the eighties publishing boom went bust

LESLIE BENNETTS

Business

eld at a hot downtown-Manhattan restaurant that has long since closed, the party to celebrate the third anniversary of American Health was loud and lively. The magazine was a success, and its founder, Owen Lipstein, was being hailed as a publishing wunderkind for anticipating the fitness boom of the 1980s. Lipstein—a high-spirited bachelor who loved to party with nubile models—was in his element that night, surrounded by admiring young staffers, advertisers, agency representatives, and other well-wishers. Lipstein’s parents watched the goings-on with some amazement. “You must be very proud of your son,” said one American Health employee. He was stunned when Lipstein’s mother replied, “We never expected Owen to be a success.”

In some ways he did seem an unlikely prospect. While other yuppies dressed for success, Lipstein, who boasts about graduating at the bottom of his class at Hotchkiss, wore jeans and cowboy boots and refused to put on a tie. He ran his publishing company more like a coed

fraternity house than a buttoned-down business. There were pizza-and-beer bashes every Friday, pina colada parties on summer afternoons, junk-food eating contests in the office, staff excursions to amusement parks on Saturdays. Not that Lipstein wasn’t serious about what he did, but he prided himself on the atmosphere at his New American Magazine Co. “It was like a mystical kingdom where the kids got to play by their own rules—and win,” says Lipstein, who calls himself the Boy Wonder.

And for a long time, he seemed to be just that. After all, by the end of the eighties he was rumored to be worth $40 million or more. Full of grandiose ideas and unlimited self-confidence, Lipstein typically juggled a dizzying array of projects; by late 1990 he was gearing up in a big way with three national magazines in production. On one floor, New American’s cavernous office space was occupied by Smart; Lipstein had just hired Peter Kaplan, the former editorial

director of Manhattan,inc., to redesign the struggling men’s magazine to compete with Esquire. On another floor, the staff of Mother Earth News was charged with making it into the voice of the environmentally conscious nineties. Still more offices were occupied by a staff working on a reconstituted Psychology Today. “It was like the Miles Drentell advertising agency on the set for thirty something," says Kaplan. “Almost everyone was young and the staff was kind of lean and New Agey, but with a sense of humor.”

Lipstein’s recent performance had been particularly noteworthy; he began 1990 by selling American Health to Reader’s Digest for $29 million—not a bad haul for a magazine he had thought up in 1981 as a cocky twenty-nine-yearold. Last August, Lipstein announced a new deal with J.I.C.C., a Japanese communications conglomerate which would receive a 50 percent stake in New American in exchange for a welcome infusion of cash. The initial installment of $3 million prompted a surge in hiring as Kaplan signed on and brought others with him, and in little more than a month he had put together a handsome new Smart. But when the issue was ready to go to the printers, he suddenly got a shocking phone call from Lipstein. There wasn’t enough money even to order paper, let alone to print and distribute the magazine. By December, Lipstein had summoned all his employees and announced that his much-vaunted Business

deal with the Japanese hadn’t been consummated after all and he was letting everyone go. “He gave this cataclysmic news, and then he said, ‘Well, at least we can have one of the great parties of all time,’ ” reports one former employee. “There was this deathly silence. People with mortgages and children were going to be hitting the streets in the worst job market in twenty years, and here was Owen, like some eighteenyear-old, saying, ‘At least we can have a few pops.’ People were furious.”

As New American disintegrated, it left an army of outraged creditors in its wake. By then, however, such stories had become all too familiar. Indeed, in many ways Lipstein’s saga is emblematic of the entrepreneurial era in which he made his mark. Lipstein typified the gogo yuppie bravado of the eighties, sailing through the decade acquiring new properties and taking on new debts as if the good times would last forever. “He was a victim of the eighties,” says Bob Lieb, one of Lipstein’s many creditors. “The banks were throwing money at him and it was irresistible; he was like a kid in a candy store.” Lipstein’s fate is particularly symptomatic of the magazine business; after a heady period that saw an unusual number of start-ups and acquisitions, the boom went bust with a vengeance. Even for a field where the attrition rate is always high, the number of fatalities has been startling. Among the dead or missing in action are Egg, Wigwag, Savvy, Fame, Woman, 7 Days, Taxi, Model, Memories, Men’s Life, Personal Computing, Unique, Exposure, Cook’s, Business Month, New England Monthly, and Long Island Monthly—and that’s not even counting Lipstein’s three contributions to the body count.

If Lipstein’s roller-coaster ride is an unmistakable metaphor for the painful transition to the grimly sober nineties, his peers see another dimension as well. “He’s a symbol of our generation,” says Chris Kimball, New American’s former publishing director. “We grew up in the sixties, in a great boom decade, and we got to our real earnings potential in the eighties. This generation, more than any other, has never had to grow up; because it was such a prosperous time, it’s been easy street for all of us. We thought we were going to reinvent the world, but it comes down to something much smaller. It’s about making unglamorous day-to-day choices. It’s about how to pay the mortgage and where to go for your ten days of vacation. The nineties are about a

generation growing up. That’s Owen’s next phase.”

Hunched on a sofa in his office, Lipstein is trying desperately to make a deal with me. The scene is one of desolation: New American is now a vast expanse of deserted office space, with empty desks, telephones stilled, equipment idled or repossessed—the electricity has even been turned off in some quarters. “It looks like Saigon after the fall,” a former staffer told me. But if Lipstein is chastened, he is hardly resigned. Right now he wants me not to publish this article about him until after his long-awaited deal with the Japanese investors is concluded—it’s just around the comer, he assures me—so that my story will have a happy ending. He is willing to offer me anything; if I’m worried about being beaten by The New York Times when his deal finally goes through, he’d be happy to give me an exclusive. Unfortunately, I happen to know that Lipstein has already promised the Times an exclusive on this same news. Lipstein has been insisting for the better part of a year that this deal is a few weeks from completion, and it still hasn’t happened. But he is so persuasive that if I didn’t know better I would surely find him irresistible.

“This is why he literally drives people mad,” says one former employee. “He is talented enough at delusion that he can create a picture of reality that doesn’t bear any relation to reality, but that people buy into—-and then when it falls apart, they’re furious. They become obsessed with him, the same way divorced people who are owed alimony sit around all day not only talking about the money they didn’t get but hating the person who deluded them.” Indeed, being mad at Owen Lipstein is a consuming passion for an amazing number of people; the landscape is littered with embittered former employees, associates, and creditors. It’s not just the $30 million or so he owes that sends them into a frenzy. What sticks in so many craws are the lies of omission and commission, the broken promises, the betrayed trusts. Even the trade press, which once hung reverently on Lipstein’s every pronouncement, has turned on him.

“Why does everyone hate me so much?” Lipstein asks. His wide eyes are hurt and guileless; April marked his fortieth birthday, but his are the eyes of a wounded child who doesn’t understand

why he’s been kicked in the stomach. “I went from being the golden boy to an asshole in about a month,” he says wonderingly, “and the rest was just like some gothic tale of horror.”

Lipstein sees his downfall primarily as a function of circumstances beyond his control, starting with the deteriorating economy. But as with most rise-andfall stories, those who know him well tend to believe that the ultimate key to Lipstein’s demise is character, and that the same qualities that made him a successful entrepreneur eventually ensured his self-destruction. At his best, he had great strengths, starting with a gift for salesmanship. “Owen is probably too bright for his own good,” says Richard LePere, a magazine consultant. “He could charm his way into things that under normal circumstances, if Joe Schlepp came in, the bank would have thrown him out on his ear.”

From the time he founded American Health, Lipstein also seemed to be in sync with the vagaries of popular culture. “He very much had his finger on the pulse,” says John Suhler, president of Veronis, Suhler & Associates, the investment bankers who handled several of Lipstein’s deals. “He had good ideas about what to do with the magazines from an editorial, publishing, and marketing-conceptualization point of view. Had he spent as much time thinking through the financing required to do the magazines properly, I think the outcome would have been very different.”

On paper, Lipstein’s vision made a lot of sense. “He owned three magazines which were, as a triad, a very good articulation of what the nineties were going to be about,” says Peter Kaplan. “Smart was supposed to be the magazine for the man of the nineties—sexy without sexism. Mother Earth News was the great green magazine, and Psychology Today was about the inner life of the new society. That would have been a great one-two-three for him.” The problem was that in the very act of acquiring the magazines he took on so much debt it became impossible to operate them. With Lipstein, numbers are slippery little critters; trying to pin him down on the figures is like trying to nail mercury to the wall. He says he bought Mother Earth News in 1985 for $7.5 million, but Bob Lieb, one of the sellers, reports that it was more like $10 million. Lipstein tells me one day that he spent $6.5 million to buy Psychology Today in 1988; another time he tells me it cost $8.5 milIf not, it wouldn’t be an unprecedented departure for Lipstein; according to any number of disillusioned ex-staffers, his relationship with the truth can be highly negotiable. “Owen is totally amoral,” says one. “It wasn’t just that he was dishonest. He didn’t think he had to be honest. He didn’t think it applied to him.” When Lipstein ran out of money, magazines started to be sent out late or not at all, but he refused to acknowledge what was happening. “He went into a big meeting at an advertising agency

“I went from being the golden boy to an asshole in about a month,”

Lipstein says wonderingly.

Business

“It wasn’t just that he was dishonest He didn’t think he had to be honest He didn’t think it applied to him.”

lion. He also spent more than $3 million trying to establish Smart under its original editor, Terry McDonell, who has since become the editor in chief of Esquire. Those were significant amounts of money for a perpetually undercapitalized enterprise like Lipstein’s, and they were far from his only debts. “It was an age when you talked about assets instead of liabilities,’’ Lipstein says wryly. “I was always assured that my net worth was big-time double-digit. So I had debt. So what? The banks were just dying to give you money, and for a boy who was told he could do no wrong, these all seemed like good ideas. No one bothered to do some old-fashioned arithmetic, like what happens when you have to pay the damn thing back.’’

Lipstein seems to think this should have been somebody else’s responsibility, and he spends a lot of time railing against the banks and bankers who led him astray. Indeed, in the final analysis he sees himself as a victim. “I feel I’m essentially heroic,” he says. “I think I’m far more sinned against than sinning.” Those who know him well simply shake their heads. “He’s the ultimate case of complete denial in his failure to accept blame for what happened,” says one former employee. “The fact is that he was a successful entrepreneur and a terrible manager. But he’s a complete adolescent. It’s always everyone else’s fault.”

Lipstein gets a vague, distracted look on his face when asked how he thought he could sustain the crippling load of debt he had amassed, which was so enormous that the $29 million from

Reader’s Digest barely made a dent. “I thought I would think of something,” he says. “I had talked my way out of so many jams, it was inconceivable to me I could get hurt, let alone downed.”

That was part of the problem. “He had this attitude that he had always been successful in the past, so anything he did would turn out all right,” says one former associate. For a long time, Lipstein did seem to lead a charmed life. “My life was better than my dreams, and I had pretty heady dreams,” he says. But no matter what the acquisitions or the accolades, Lipstein was never satisfied. “He was going to be the rock star of publishers,” says a friend. Lipstein spun off ideas at a dazzling rate, and his staff was perpetually scrambling to keep up with all the ancillary projects they were supposed to handle. According to T George Harris, the former editor in chief of American Health, by the time of the sale to Reader’s Digest, the magazine or elements thereof could be found on computer information services and on public television, in mail-order courses and books, on audiotape and videotape and the touch-screen kiosk at your neighborhood pharmacy. Then there was the wall-board media service called Fitness Bulletin, which was distributed to health clubs. Chris Whittle had already established such a service under the aegis of Esquire, but Lipstein wasn’t about to cede the Held to someone he perceived as a rival. “He wanted to be what Chris Whittle has become, so all of a sudden American Health started up the Fitness Bulletin in competition,” says one former employee. “Owen wasn’t happy just doing well. He wanted to be a publishing giant.”

The Fitness Bulletin ate up several million dollars that were needed to service Lipstein’s debt and put out the other magazines he kept acquiring. His quest was relentless; he bought an option on Taxi and another on Venture, and he looked into buying The Village Voice. “It was almost like it didn’t matter what it was; he just wanted to buy something,” says Susan Hayes, Lipstein’s former senior vice president for finance. If he wasn’t buying, he was inventing; Mother Earth News spawned a bimonthly offshoot called American Country. “The whole company always felt like we were in a start-up mode, because we were always starting up new things,” says Joel Gurin, the former editor of American Health. Nor did Lipstein bother to organize his various staffs into a

coherent administrative structure. “Chaos was the modus operandi,” reports Judie Groch, who was executive editor of American Health. “The lines of authority were never clear, and the buck was always being tossed around someplace up in the air. You never knew when it was going to fall on you.”

By the middle of 1989, Lipstein’s financial straits had reached crisis proportions. The bailout was supposed to come from Reader’s Digest, but that deal turned out very differently from the way that Lipstein had anticipated. In surveying the wreckage of his career, Lipstein has a long list of villains, but right up at the top is Tom Kenney, president of the magazine-publishing group at Reader’s Digest. Lipstein says he had agreed to sell American Health to Reader’s Digest for $38 million when Kenney arrived on the scene and decided the price was too high. In Lipstein’s version of the ensuing events, he got so angry in one key meeting that he told Kenney, “Suck my dick,” repeating it for good measure just in case Kenney hadn’t heard him the first time. “I had a big smile on my face,” Lipstein recalls. “For a moment, it was really satisfying. There are probably only about ten words in the English language that are unretractable, and I picked three of them.” Lipstein claims that Kenney then walked out of the meeting, followed by John Veronis and John Suhler, who represented Lipstein. “Congratulations, you’ve blown the deal,” they told him sourly. Four months of hard negotiations, later, the deal was eventually salvaged, but by then Kenney had gotten the price down to $29 million. Both the lost dollars and the lapsed time were devastating blows for Lipstein, who was broke.

Lipstein tells the “suck my dick” story with considerable frequency. “Owen thinks of this as one of the proudest moments of his life,” says one former staffer. The only problem is that it may be a figment of Lipstein’s own overheated imagination. “That did not happen,” Kenney says flatly, as does John Suhler.

“This isn’t going to be my obituary. This is going to be about my Houdini act.”

Business

with all these associate media directors and swore that Psychology Today had been sent out, and it hadn’t, and they all found out,” reports one high-ranking former employee. “People don’t trust him; he’s lied too many times.”

Lipstein shakes his head wearily when asked about such charges. “The simplistic explanation is that I lied,” he says. “But think about it: you build up something which is your life’s dream, and

you lose virtually all the equity you’ve built up within a twoor threeor fourweek period. How many people would go out to the advertising community and say, ‘Hey, guess what, guys, you shouldn’t advertise with me, because this deal is not going to go through, so I’m not going to have the money to put into the other magazines’? What would you do—say, ‘I’m dangerous’? I clearly did the wrong thing, but how many people would have done the right thing?”

Indeed, for all the outraged colleagues he left behind, others are more forgiving. “I think Owen is fundamentally an honest person who has good motives and good intentions,” says Bob Lieb. “Circumstances have prevented him from doing what he wanted to do, and all the little people jumped at the chance to attack. I’ve never seen anybody so vilified. What did he really do? He didn’t pay his creditors, but he’s not a devil.” Lieb’s assessment is particularly generous given the fact that Lipstein owes him and his partners millions of dollars. “I think Owen meant to pay me,” Lieb says charitably. “I think Owen always means well.”

Avast duplex with soaring ceilings and a view of the Hudson River, Lipstein’s apartment might as well be a Bloomingdale’s showroom for “Santa Fe Style.” An enormous buffalo head hangs on one wall, bleached cow skulls and a spiky set of antlers are mounted above the fireplace, an exceedingly tall pair of cowboy boots is artfully placed on the hearth. However, Lipstein is eager that nobody think he just jumped on some bandwagon. “I got Southwest before anybody else got Southwest,” he says defensively. “I was cool before it

became cool.” There is also a gleaming black piano. “Do you play?” I ask. He sighs. “No. It’s a prop. I thought I would leant, but I never did.”

There are larger commitments he hasn’t managed to make either. His father thinks that Owen has been so busy working he just hasn’t had time to marry and have children; Owen says he hasn’t found the right woman yet. “He’s a romantic,” one friend explains. “He envisions himself as F. Scott Fitzgerald, and he’s looking for Zelda.”

“There’s a nice Jewish boy locked inside this playboyWasp image he thinks he has to be part of, but he can’t fight his way out of this fancy packaging,” says June Steinfeld, who was Lipstein’s senior vice president for circulation. “One time he said to me, ‘I’m getting married!’ I said, ‘That’s great—to who?’ He said, ‘I don’t know— I haven’t met her yet.’ ”

These days there is a new girlfriend, Karen Bokram, a leggy twenty-twoyear-old Wasp from Grosse Pointe who began as Lipstein’s assistant on the book he’s writing about himself, and soon graduated to being his latest fiancee. “The book is called Cowboy Broke: Not Enough Home-Cooked Meals—How I Made and Lost Millions in the Eighties,” he says proudly. Still, even with another adoring young woman at his side, things are much quieter than in previous years. The West Village apartment used to be full of trendy-looking people, but the parties in the city were nothing compared with the perpetual bash that went on at Lipstein’s house upstate. He had bought a thirty-acre estate overlooking the Hudson River and filled it with every toy he could think of: a motorcycle and an all-terrain vehicle, guns and boats, electric guitars and motorized Jet Skis, a sauna and a hot tub and an indoor pool. With the silver-green Porsche in the drive, it was quite the bachelor’s paradise—“complete with a kitchen with no food in it and the Beatles’ ‘White Album’ on CD,” one visitor says dryly.

Now it is all in jeopardy. Lipstein personally guaranteed his debts, and if his merger falls through he could lose his house and his co-op along with his business. His parents will be hurt as well; his father, a prominent New York advertising executive before his retirement, guaranteed a bridge loan for him, and Owen says that if he goes under his dad stands to lose up to a million dollars. Owen allows that it’s “painful and em-

barrassing” for him to have cost his parents so much, but then he adds, “They can afford to take this hit. They are well-off.”

Even at forty, Lipstein is still the brash child of privilege who knows that no matter what goes wrong there will always be a cushion under him when he falls. His current difficulties are doubly unwelcome because they have forced him to act like a grown-up. “Peter Pan grows up,” he says mournfully. The scenario for survival is simple but painful: persuade his creditors to accept twenty-five cents on the dollar, and reduce his debt so drastically the Japanese finally decide the price is low enough to hand over the many millions it would take to put him back in business. The formula for failure is even more obvious: Lipstein is left twisting in the wind, and eventually he has to declare bankruptcy and slink away in defeat. With characteristic bravado, he keeps a relentless focus on the brighter scenario. “If I don’t get the Japanese deal done, I’m fried,” he acknowledged to me in February. “If I do get it done, I’ll be in very good shape. I know the conventional wisdom is that I won’t get out of this, but I bet you I will. This isn’t going to be my obituary. This is going to be about my Houdini act.”

By May, the deal was still around the comer; Lipstein was sounding considerably less confident about his erstwhile Japanese partners, but he had begun talking about some new British investor instead. “It’ll happen next month,” he assured me, as he had every month since the beginning of the year.

There are many who scoff at such boasts, maintaining that Lipstein has burned so many bridges he is surely finished. “I can’t imagine he would be able to come back into publishing now,” says Roberta Garfinkle, vice president director of print media at McCannErickson. “He’s lied to too many people too many times. It’s not so much that people hate him, they just wouldn’t do business with him. And if you believe that this deal with the Japanese is going to happen, I’ve got a great bridge I want to sell you.”

Then there are those who take the longer view. “I think he’ll be back,” says John Mack Carter, president of the American Society of Magazine Editors. “He’s too young to quit, and with a track record like his he’s not likely to be hired, so he’s got to start his own thing again. This is not an American tragedy. It’s a mini-series, and it’s not over yet. Stay tuned.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now