Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

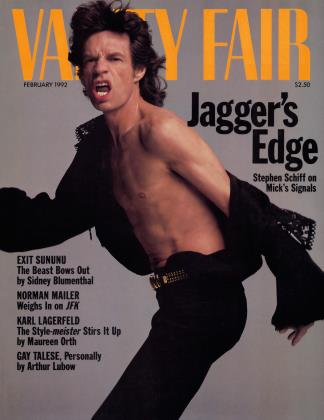

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFOOTFALLS IN THE CRYPT By Norman Mailer

Oliver Stone's new movie,JFK, has something to alienate everyone, from Establishment theorists to the gamut of conspiracy buffs. But as NORMAN MAILER writes, by daring to plumb the depths of America's nightmare obsession on the big screen, the controversial director has posed some very unsettling questions

NORMAN MAILER

hat is one to make of JFK1 It is not routine to take it on, for Oliver Stone presents a nice problem in critical assessment. These years, when the best film directors have preferred to ignore the largest themes, Stone has gone bucking ahead with all the fullbacked intensity of a heavyweight willing to endanger his body against any opponent.

Platoon, his first major success, is an example. Its story barely holds together, yet there is no need for the film to do more. Stone, better than anyone before, is showing us what it is

like to endure the physical misery of a patrol on a jungle trail. The minute-by-minute experience of slime, bugs, exhaustion, and occasional combat is conveyed; by the unspoken logic of film, that is enough. Good films need be no better than good or interesting one-night stands. They do not have to change our lives, provided they show us something we had not known before. Platoon did that. It offered a sense-filled correlative for what veterans of the South Pacific and Vietnam had been trying to explain for a long time. Since it also had the advantage of a fine job by Tom Berenger and a performance by Charlie Sheen that grew as it went along, Platoon worked.

So did Wall Street, if at a lower level. Michael Douglas, Daryl Hannah, Charlie Sheen, and Martin Sheen did responsible work, but the story, drawn from the history of a couple of financial worthies who made newspaper headlines for their white-collar crimes, was a contrivance, the cinematography was conventional, and the moral was homiletic. It seemed apparent that Stone, whatever his willingness, was not a man with a vocation for irony.

'The first thing to be said about JFK is that it is a great movie, and the next is that it is one of the worst great movies ever made.'

Born on the Fourth of July, however, came near to being a great movie. It gave us a view of the torture rack that bound those Americans who went over to Vietnam with a set of conventional beliefs, only to return with no conviction more fiercely held than that morality was equal to surrealism. In one of the best scenes ever filmed in any American movie, Willem Dafoe and Tom Cruise, marooned in their wheelchairs on a clay-dirt road in clay-red Mexican mountains, commence to argue over who has actually shot a baby in Vietnam and who is merely pretending to have it on his conscience. Before the verbal duel is over, each is spitting in the other's face. The wheelchairs tangle, fall over, and the two paraplegics wrestle on the ground, enraged that the other will not believe that, yes, I am guilty of a greater horror than you. Tumbling down together into a gully, they lie halfconscious in the dust, helpless to move, and never are we more aware of their broken spines. That scene captures as much of the war in Vietnam as did Coppola's Valkyrie ride of helicopters in Apocalypse Now. Yes, Born on the Fourth of July was close to being a great movie, but the logic of its inner development was tenuous, and so, despite Cruise's exceptional performance as Ron Kovic, we were only partially convinced that he ends as a radical. Yet what a large and ambitious attempt had Stone undertaken. The size of the gamble underwrote the cruder means. Lack of fear can take an artist into places his skill does not permit.

By the time Stone made The Doors, he must, given his boxoffice successes, have been choked with hubris. The Doors has to be one of the truly bad movies of all time, albeit with a prodigious distinction, for it is also virtuoso. It has not one mass scene, but three dozen. Since the demands on a film crew shooting a single mass scene are uncountable, the toll on assistant directors must have been catastrophic. The Doors, almost two and a half hours long, probably has two hours of scenes with fifty to five hundred extras. It provides us with the experience of a rock world, but at the harsh cost of living in it. Half-glimpsed wonders of a half-muttered and half-uttered Dionysian life just about convert us to the Apollonian.

It is possible, given Stone's enormous ambition to take on

none but the largest American themes, that he had decided this once (since rock's apocalyptic promise to break through into a brave new consciousness was now two decades dead) that he would shift his interest from wild frontiers onto unparalleled technical difficulties; he certainly brought that much off. At a time when other directors, for lack of heart or certainty of theme, have all been heading toward technical splendor, The Doors goes even further into kaleidoscopic cinematography. All of Stone's faults, however, were compounded—his lack of grasp for what a good script can be, his heavy-handed hold on mystical states, and his disjunctive narrative sense of how protagonists can grow, or be destroyed. It may be that the virtue of The Doors is that it cleared the decks for something larger.

We come, then, to JFK. It is the boldest work yet of a bold and clumsy man, but the first thing to be said about it is that it is a great movie, and the next is that it is one of the worst great movies ever made. It is great in spite of itself, and such greatness owes more to the moxie of the director than to his special talents. Nonetheless, it is an incomparable experience which moves into parts of our heart that we have anesthetized for years.

So one's first judgment is that it cannot be discussed as just a film; it is not of the first interest to talk about where JFK works cinematically and where it does not. One does better to treat it as a psychic phenomenon, a creature in the dream life of the nation, and this is legitimate; film, at its most compelling, lives in our mind somewhere between our memories and our dreams. One of the most advanced art forms of the twentieth century is, therefore, one of the most primitive as well, or, at least, such a claim can be invoked when we are dealing with the sinister edge of serious film on a large screen in a dark theater. In that sense, Stone's instinct proved superb.

Subjects as heroic in scope as J.F.K. can be as uniquely suited to film as is a good kill to a tribe of hunters, and if the prize was obtained at considerable peril to the chief hunter, then it barely matters how the meat is cooked. Need, and the nature of the exploit, flavors the repast. JFK is bound to receive some atrocious reviews, perhaps even a preponderance of unfavorable ones, and, as has been the case already, more than a small outrage is likely to be aroused in the Washington Club (that is, The Washington Post, Newsweek, Time, the F.B.I., the C.I.A., the Pentagon, the White House, and the TV networks on those occasions when they wish to exercise their guest privileges). The Establishment has found that Oswald-as-the-lone-assassin serves a multitude of useful purposes, in much the way that a public figure who wraps himself in propriety, no matter how greasy his private life may be, has a dependable political seat. Studying such prizes on television, we know they lie—the gross and subtle folds of corruption onthe average senatorial face are hardly the lineaments of virtue— but we can also recall that nobody who played at being a puritan during the Thomas-Hill hearings had to move off his dime. Rectitude planted all the flags.

Ditto for the lone assassin. The F.B.I. was the first to endorse the idea, and this but two weeks after the death of J.F.K. In 1964 the Warren Commission came down foursquare behind that finding. Over the years, however, the Warren Commission lost its credibility. The polls give the figure: a majority of Americans now believe there was more than one killer. That, however, is naught but belief. It is the actions of men that make history, and the majority of action in this case has been taken over by the Washington Club— they have circled their wagons around the lone assassin.

It does not matter that in 1978 the House Select Committee on Assassinations decided, on the basis of the acoustic evidence, that there had been a fourth shot. Since it was agreed that no rifleman, no matter how skilled, could get off four aimed rounds from a Mannlicher-Carcano bolt-action rifle in 5.6 seconds, that meant there had to be a second assassin. While this opened a fell crack in the granite wall of lone-assassin solidarity, the committee's thirty-month mandate expired even as it was making the discovery, and its work was not extended. Instead, the Department of Justice was handed its files, with a full invitation to look into the new findings. The Department of Justice and the F.B.I. are still looking—that is about equal to saying that the files pertaining to the case have presumably not been destroyed. Of course, about as much may now be left of such documents as still adheres to an automobile after it has been abandoned on a slum street in the South Bronx. And the House committee's own backup records and unpublished transcripts have been sealed as "congressional material." They won't be made public until the year 2029. We may be witting to the all-butabsolute certainty of a fourth shot by a second assassin, but we are still living in the land of upper maintenance men; they look to keep their establishment intact. So in 1988 the Department of Justice announced that the House committee had misinterpreted the acoustic evidence. How not? The price is too prodigious if there was more than one demented gunman. Two assassins not only have to be able to function in concert, but, by their effectiveness itself, suggest a support system, which is to say a larger conspiracy.

At this point, many an old horror arises. Did Castro have a hand in it? the American left must try not to ask itself again. No, of course not, he had too sure a sense of the consequences is the reflexive reply, but then, who can be certain that individual members of the D.G.I., Castro's intelligence service, had not been engaged in some mutually deceptive game with Cuban exiles in Florida and Texas? Even worse for the national polity is that our political center must ask itself, Could Lyndon Johnson, who, we now seem to be learning, was capable of just about any deed, have ordered it? Certainly not, replies the center, and just as reflexively. Yet how could Lyndon Johnson, even if wholly innocent, have ever been certain that some of that bold Texas money, nudging him through the years, had not decided to take a flier on its native son? Nor could Richard Nixon be certain of immaculate innocence. He had been in contact with Cuban exiles for many years, and some of them had not been without murderous ideas. Could the C.I. A. know its own stables were clean after their hit-man dealings with the Mafia? Rogue elephants were capable of fancy steps that put ballet dancers to shame. And then, for that matter, who was Oswald? By now, there is more evidence to suggest that he was sent to Russia as a ploy of U.S. intelligence than that he went over on his own. Could the Pentagon afford to look closely into its most special contingents? Could the F.B.I. live with a second rifle after all these years of being signally unable to improve on the absurd tale of one gun? Could those headmasters of the Washington Club's conscience, The Washington Post and its often concordant satellites, Time and Newsweek, live with an unresolved conspiracy after being for decades loyal apostles of the lone assassin? No, it was to the interest of left, center, and right to remain unaffected by the House select committee's findings. Even if, in light of the new evidence, a second assassin could not be denied, it had to be realized, when you got down to it, that a lone assassin was what we had been living with all along. Headmasters do not traffic with the novel and the unforeseen.

When Oliver Stone charged, therefore, in full panoply with all his filmmaking teams and equipment into the valley of assassination enlightenment, there were heavy guns emplaced on the right, and on his left were all the inflamed ragtag assassination buffs. They had been working in relative solitude for decades, laboring on in the private, inspired, and isolated hope that one day they would uncover the mystery and be renowned forever.

It was a fantasy. The best and most skilled of the assassination buffs knew as much by now. To the degree that the murder of J.F.K. was a conspiracy, so could one assume that the most salient evidence and the most inconvenient witnesses had been removed long ago. Yet a buff could only persevere. It had become one's life. It had become, so far as the universal need for personal power is concerned, a way of life. If one could not solve the assassination, one could at least mow down the theories of other researchers who tried to squat in proximity to the barren acres of one's own land grab.

So, the parvenu, Oliver Stone, endowed with all the wealth, muscle, and arrogance of a $35-to-$40-million budget, and no great willingness to become enmeshed with the majority of assassination buffs, naturally encountered trouble on both flanks. The buffs might not have been a well-organized army like the Washington Club—no, by comparison, they were Bushmen with blowguns—but some of them were ready to collaborate with the big guns on the right.

The attacks began before movie shooting even commenced. George Lardner Jr., the resident writer on intelligence matters for The Washington Post (which is to say the friend and confidant of many an F.B.I. and C.I.A. man), obtained a stolen copy of the JFK script, and did a long piece about Stone for the Club on May 19, 1991.

His hero: former New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison, whose zany investigation of the assassination in the late 1960s has almost faded from memory. . .Oliver Stone is chasing fiction. Garrison's investigation was a fraud.

Stone has said that he considers himself a "cinematic historian" and has called the assassination "the seminal event of my generation." But Harold Weisberg, a longtime critic of the FBI and Warren Commission investigations of the assassination . . .protests, "To do a mishmash like this is out of love for the victim and respect for history? I think people who sell sex have more principle."

. . .D.A. Costner assails the murder as a "coup d'etat"— hold your breath—ordered by "a shadow government consisting of corrupt men at the highest levels of the Pentagon, the intelligence establishment and the great multinational corporations," carried out by elements of the intelligence community and covered up "by like-minded individuals in the Dallas Police Department, the Secret Service, the F.B.I., and the White House— all the way up to and including J. Edgar Hoover and Lyndon Johnson, whom I consider accomplices after the fact."

The screenplay ends the Sunday Oswald was killed with a White House scene of Johnson meeting with his Vietnam advisers. "He signs something unseen" and tells them, "Gentlemen, I want you to know I'm personally committed to Vietnam, I'm not going to take one soldier out of there till they know we mean business in Asia."

That is nonsense. . . . All the hoopla, of course, will obscure the absurdities and palpable untruths in Garrison's book and Stone's rendition of it.

The manuscript smuggled over to Lardner had been a first draft, and Stone and his co-writer, Zachary Sklar, were to rewrite the script five times. Stone would later reply, "I've taken the license of using Garrison as a metaphor for all the credible researchers. Lardner... narrows the focus of the picture to his enmity for Garrison, whereas this is not the specific Jim Garrison but an all-encompassing figure."

Played by Kevin Costner in restrained and dignified fashion, the Jim Garrison of the film is, by any rough and living measure, too good to be true—an honorable D.A. consumed by an inner passion to find the light and save the land. If the real Jim Garrison had to be outrageously brave, staggeringly ambitious, willing like many a district attorney before him to cut a few comers, and vain enough to take on the moon, Costner is directed to play him as heir to Mr. Deeds and that particular Mr. Smith who once went to Washington. Wideeyed, open, fearless, and consumed by his work, he is indefatigably fueled by his ideals. His only vulnerability (other than to the classic nagging of his wife, Sissy Spacek, who finds the children and herself ignored as a result of the exigencies of inquiry) is that he is innocent of guile and so has no built-in bulwark against the tide of horror he feels as he encounters the all-pervasive manipulations that are stifling his attempts to uncover the true conspirators responsible for the death of J.F.K.

In this mythic Wagnerian vein, the movie goes back to the primitive roots of silent film when each character was an attitude or a force or a spirit or a project—I will clear the forest, I will find the magic sword. Garrison/Costner takes off after evil, and is unhorsed over and over again by a variety of foul obstacles (the C.I.A.) and treacheries (a trusted associate). Always he gets up, always he goes on. At the end, defeated in his attempt to convict the immediate target, Clay Shaw, of conspiracy to murder the president, Garrison/ Costner is nonetheless redeemed because he is in the right. He will prevail, or if he does not, the good fight will prevail, and if not in this venture, then in another. Many a silent film was built on the vision that virtue is equal to light and will take us through the dark—it was what the pianist was always telling us from the pit.

There should be no surprise, therefore, if the narrative jerks and manhandles us around many an unnegotiable turn. The film has a large conspiracy thesis that cannot be encompassed by the likes of Clay Shaw and David Ferrie and the supposed link between them as homosexuals. That does not provide us enough drama to assure us, as Lardner warned, that the Pentagon masterminded the assassination in response to J.F.K.'s desire to take us out of Vietnam. Nor does it prepare us for Garrison/Costner's final measure of the conspiracy, which includes elements from the C.I.A. and the Mafia, the F.B.I., the Secret Service, the Dallas police, and, yes, J. Edgar Hoover and Lyndon Johnson, accomplices after the fact who directed the cover-up. It is a paranoid installation the size of a space city on the moon, yet we come faceto-face with it in just two scenes, each didactic, each expository, and neither emerges from the action.

In the first, Garrison/Costner, all but defeated by the three-quarter point of the film, weary, spiritually burdened, and in need of recharging his missionary batteries, decides to visit Washington, D.C., and look around, ask around. He pays a visit to the Lincoln Memorial, and as he emerges onto the portico, a mysterious figure in a dark raincoat and a small gray checked fedora of precisely the sort that we expect an intelligence officer to wear comes into the frame and introduces himself. It is Donald Sutherland. In the next few minutes Sutherland explains it all—who killed Kennedy and how, and what steps Garrison/Costner can take. It was the military—Sutherland now offers—who did it, and with a wise smile he informs us of how he knows of what he speaks: as a member of an ultra-covert military outfit, he has long been geared for elite, high-tech snuff jobs. As they stand side by side in a drizzle, Sutherland fills Garrison/ Costner in on how the Pentagon set up the assassination. "Testify," says our hero. "No chance," says the informant, and in another moment he is gone. It is all but the return of Deep Throat.

It could have been one of the more embarrassing moments in recent film history. Given our contemporary film canons, the use of such a scene is analogous to approaching the bed of one's beloved with a dildo larger than oneself. Yet Sutherland shows us what a talented actor using quiet means can accomplish in a scene that might be intolerable if anyone else tried to bring off this expository implant.

A little later, in the penultimate scene, at the conclusion of the Clay Shaw trial, Garrison/Costner comes up with a speech to the jury that is beyond the reasonable limits of any court; in that speech the cause of Kennedy's death is restated. He desired to get out of Vietnam, says Garrison/Costner, and Lyndon Johnson wanted to keep us there. So we have had a changing of the guard. Before it was over, every dark force in America had made its contribution. A case that has not been proved at all in the scene-to-scene details of the film now again delivers a final and arbitrary conclusion. We have been treated to not one deus ex machina of exposition but two, and at the very end, case lost (and indeed we, the audience, have been given no more real connection between Clay Shaw and the assassination conspiracy than was the actual jury), Garrison/Costner, reunited with his wife by the force of his pleading in court, walks out hand in hand with her and with their children, and we see the family in a corny long shot at the other end of the courthouse lobby.

'Oliver Stone has mislabeled the product. He has not made a cinematic history, and, indeed, to hell with that!'

How, then, is JFK a great movie?

Let us commence with what is needed for a great history (as opposed to a great movie). Such a work not only would require a comprehension of the forces and tides that shape and convey an era, but would also be obliged to possess a special species of pointillism; its thousand diverse points of light ought to be details chosen well enough to buoy the history with resonance. That, however, cannot be asked of any movie. Films, we are bound to repeat, live between memory and the dream. A great film may be epic, operatic, panoramic, stoic, and certainly it can be mythic and embody the more powerful legends of our lives, but any attempt at cinematic history has to be an oxymoron. Oliver Stone, like many a movie man before him, has mislabeled the product. He has not made a cinematic history, and, indeed, to hell with that! He has dared something more dangerous: he has entered the echoing halls of the largest paranoid myth of our time—the undeclared national belief that John Fitzgerald Kennedy was killed by the concentrated forces of malign power in the land. It is not only our unspoken myth, but our national obsession: we have no answers to his death. Indeed, we are marooned in one of two equally intolerable spiritual states, apathy or paranoia.

That is a large remark, but it may fit the condition of our time. Since the death of J.F.K., we have suffered the moral disruption of Vietnam, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, the flatulent host of petty mysteries concerning Watergate—why ever did it happen, and what, in fact, took place? Like a battered wife, we have borne our national obsession through Carter and stagflation to be revived for a time by the Pied Piper; he, in turn, wrecked our economy in the course of cheering us up and defeating the Evil Empire. Of course, that Evil Empire was already on the way to expiring in its own dust, but we were ready to accept much hypocrisy (and future bankruptcy) to avoid living with dread.

For what is obsession but a black hole in our psychic space, a zone of ambiguity into which our energies flow and do not return? A nearer example to many of us: when a marriage ends in uncertainty and neither mate knows within who is more at fault for the divorce, then an obsession has commenced. One goes back again and again to the question: Was one more right than wrong, or more wrong than right? Fear stirs, precisely the fear of spiritual consequence. It is then that the ego—its hand on the throttle that will keep us moving forward—discharges funds of assurance. One must keep up the certainty that one is right even when one does not know, and somewhere, off to the side, one wonders if one's will is being corroded.

If that is the cost of personal obsession, what is one to make of the million-headed, or is it, rather, the hundredmillion-headed, deficit of the national obsession? There have been moments in our history when all Americans have found themselves together for an hour in the same stricken space. Pearl Harbor was such a day, and the death of Franklin Roosevelt may have been another. The hour in which we learned of the bomb on Hiroshima had to be another. On that day, the new concept of atomic energy spoke with equal force to the idea of a new civilization and to the terror that all civilization would be destroyed. If that is, by now, an inter-

national obsession so large that the fears are cosmic, the assassination of J.F.K. remains as the largest single event in the history of nearly all Americans who were alive that day. No afternoon in the recollection of our lives is equal to November 22, 1963, and in its aftermath we lost our innocence and had to decide whether life was absurd (for one demented assassin could swing the ship of state wholly off its course) or, worse, whether the route of the ship of state had been so determined that even a president, wishing to change the given, was hurled off the bridge. We have lived with that question ever since. Do we descend into paranoia, or suffer the tedium of an apathy that tells us we will never know and so may as well accept the theory of Oswald as the sole killer? There is a profound reason why the Washington Club clings to the lone assassin and the incredible bullet that passed at many an angle through both Jack Kennedy's body and John Connally's body—apathy is easier to endure than livid inquiry; a dubious set of unsatisfactory facts disrupts much less than does an all-out, full-scale investigation. Just as a good lawyer never asks a question to which he does not have the answer, at least not if he can help it, so the Washington Club does not pursue the assassination. For no one knows, unless there is someone who does know, where it may all end.

JFK is false probably to the likelihoods of whatever conspiracy did take place, since it is all but inconceivable that a major plot involving the Pentagon, the C.I.A., the F.B.I., and the White House could ever hold together through the decades. Yet, the horror persists: if the assassination were not an absurdity committed by one man in a surrealistic universe, nor even a foul deed brought (Continued from page 129) off by a few determined operators who managed to remain undiscovered because the real powers of the nation were all terrified of their own possible implication, so terrified that evidence was buried and all real inquiry paralyzed—no, what if it were even worse than that, what if the assassination was designed by powerful people for large purposes? Once, as a guide for approaching political questions that do not have a quick answer, Lenin laid down the axiom "Whom? Whom does this benefit?" and by that measure, yes, to the degree that history conforms more or less directly to the needs of power and policy, then, yes, if Kennedy was going to end the war in Vietnam, he had to be replaced; Lyndon Johnson was the man to do it.

Continued on page 171

(Continued from page 129)

History, rarely tidy, is not always so functional. Stone's movie offers us the overarching paradigm, not the solution, and that becomes a large part of its power. It is a crude movie driven home with strong colors and heavy strokes, as indeed all of his films have been. He is one of our few major directors, but he can also be characterized as a brute who rarely eschews that heavy stroke. All the same, he has the integrity of a brute, he forages where others will not go, and the result is that we live for three hours in the ongoing obsession of our national lives. (Be it recognized that, while our psyches are obviously devoted in the main to our private concerns, larger and larger grows the national sector of our souls.) So we descend again into that obsession to which we know it is better not to return, that dark land where no answers are provided. It is amazing how powerful the film becomes. Even when one knows the history of the Garrison investigation and the considerable liberties that Stone has taken with the material, it truly does not matter, one soon decides, for no film could ever be made of the Kennedy assassination that would be accurate. There are too many theories and too much contradictory evidence. Tragedies of this dimension can be approached only as myths. Here, the one that we are witnessing exerts upon us the whole force of Greek drama, and we return again and again to that national chorus of which we were a part on November 22, 1963—we live again in the mystery, the awe, the horror, and the knowledge that a huge and hideous event did, yes, take place on that day, and the gods had warred, a god fell, and the nation could never be the same.

It did not have to be Oliver Stone who made this film. Another director and another script bearing on the same events would have been as powerful if it had dared as much, but Stone is entitled to the kudos he will probably not receive, for he was the first to enter the caves of this obsession and live in them through the year and more of writing, shooting, editing, and being assailed by the media; he was the first moviemaker to be fevered by the heat and chilled with the terror that what he was daring to say about this assassination could keep him sleepless, and will, I expect, until he learns whether this huge gamble, this spelunker's reconnaissance into the caverns of the American horror, will be well received at the box office or rejected by a new generation of television Americans who will choose no aesthetic experience powerful enough to stay with them into the morning after. If so, then the question to ask is whether the attempt to capture greatness has become the most unacceptable aesthetic endeavor of them all. In that case, JFK, the crudest of the great movies, but a great movie, will have to rest in peace.

That is one scenario. If, on the other hand, JFK proves successful, then there is no way in which the point will not be raised by Lardner & Co. that Stone's mythic presentation of the murder of President Kennedy is a monstrous act, for it is going to be accepted as fact by a new generation of moviegoers. One can only shrug. Several generations have already grown up with the mind-stultifying myth of the lone assassin. Let cinematic hyperbole war then with the Establishment's skewed reality. At times, bullshit can only be countered with superior bullshit. Stone's version has, at least, the virtue of its thoroughgoing metaphor.

A coda. Reviewing Thomas Reeves's book on John Fitzgerald Kennedy's private life, A Question of Character, Jonathan Yardley, the book-review whip for The Washington Post, offered these neo-puritanical comments the Sunday after Lardner's attack on Oliver Stone appeared:

[Reeves] undertakes to assess Kennedy not merely in political or mythological terms, but in moral ones.... Though Reeves does not quite come right out and say so, his analysis suggests that the assassination of John F. Kennedy, however cruel and ghastly, may have spared the nation something even worse than the prolonged orgy of grief and hagiography that followed it. He suggests that the gentlemen's agreement by which details of Kennedy's private life were kept secret might well have been violated, for whatever reason, during a second term, and that a vote of impeachment might well have followed.

This, had it come to pass, could have been more damaging even than Watergate. The spectacle of a president of the United States on trial for illicit liaisons within and without the White House, for questionable relationships with ranking figures of the underworld—this would have been more than the United States of the mid-1960s could have stomached. The proceedings would have tom us apart in ways we can scarcely imagine, and left us with a cynicism about politics by contrast with which the residue of Watergate would seem a mild case of disenchantment. Better that the handsome young president died a mythical if not actual hero, and that the true story of his character emerged so tentatively and gradually that we were given time to come to terms with it. Had we been forced to bear in a single blow the full import of the story Thomas Reeves tells, it would have shattered us.

What this singular assessment provides is the new notion that the determination to get rid of Kennedy, if it had failed in the overt attempt, might well have moved on to impeachment, a more protracted affair. So we are free to wonder, having been given not only the presidential models over the last three decades of Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, and Bush, but also the secondary examples of Humphrey, McGovern, Mondale, and Dukakis, whether any protagonist as innovative, flexible, daring, ironic, witty, and as ready to grow as Jack Kennedy ever did have a chance to change the shape of our place.

Or is it that we will do anything to get rid of an obsession, even buy the proposition that the guy who gives us the problem in the first place is better off dead? The Washington Club has many mansions, and Yardley Court is the newest.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now