Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSARGENT'S PEPPER

MARK STEVENS

This month, Washington, D.C.'s National Gallery of Art explores how John Singer Sargent, who captured society with such perfectly cool aplomb, created his hot-blooded sensation, El jaleo.

Sargent was the last artist able to endow the stylish rich with something akin to grace.

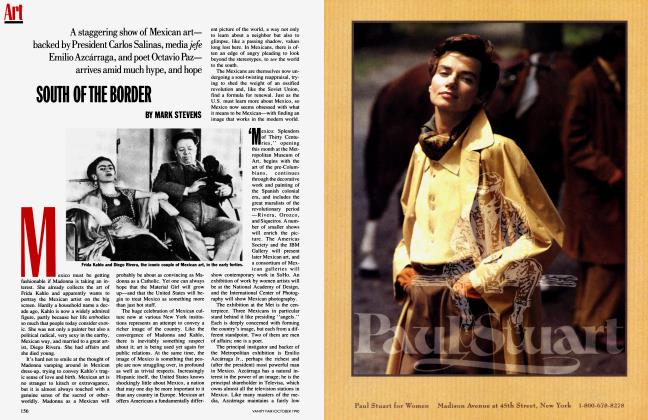

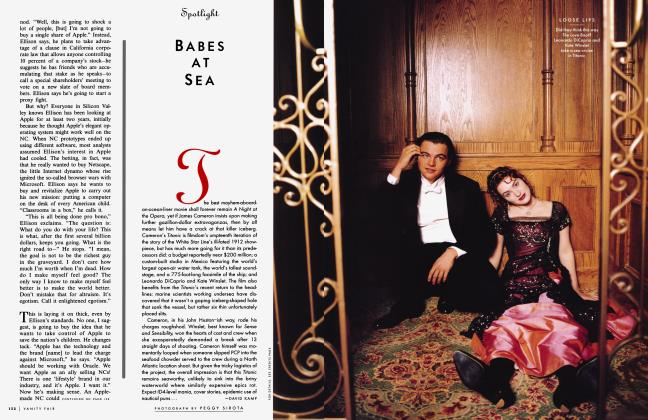

In 1882, the twenty-six-year-old American expatriate John Singer Sargent set out to become the talk of Paris. He had a genius for pleasing, so he did not challenge or provoke the governing taste. He aroused it. Knowing that the idea of an exotic Spain thrilled nineteenthcentury Parisians, he worked up one of the greatest of all southof-the-border pictures—El Jaleo, a sultry, life-size portrayal of a Spanish flamenco dancer in mid-strut. Nothing about the picture is restrained. Could there be in all of art, for example, a more prominent nostril? The dancer is so hot-blooded she seems about to snort steam.

As Sargent had hoped, El Jaleo became the conversation piece of the Paris Salon—and the curtain raiser for his brilliant career as a chronicler of the rich and stylish. The legendary Boston collector Isabella Stewart Gardner, who eventually owned forty-four of his pictures, ended up with El Jaleo; it has not moved from her museum since 1914. Newly cleaned and on loan for four months to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., El Jaleo is now the centerpiece for a seductive little exhibition about the making of a single, celebrated painting.

By gathering together a number of related works and preliminary studies for the painting, the show's organizers have demonstrated how hard Sargent labored to make his splash. They have also made a point of the French vogue for Spain. Many important artists of the time— pre-eminently Manet—took a nearly obsessive interest in Velazquez and Goya. There was, besides, the romantic conviction among pasty Parisians and northerners generally that the sex must be better (more passionate, earthy, theatrical) down there. For many people, El Jaleo is the Carmen of paintings.

But the exhibition also has a trickier sort of interest, having to do with the vexing question of just what to make of Sargent's great gifts. To this day he remains both the most underrated and the most overrated of artists. Some delight in his facility and bravura handling of a loaded brush; others consider him a shallow virtuoso, a pussycat of the rich—a brilliant society portraitist, perhaps, but isn't that just fluff and feathers in the era of Cezanne? In fact, Sargent has a fascination beyond yea or nay. His superficiality is mysterious. It even conveys an important sadness.

He had a bizarre upbringing. His father, a Philadelphia doctor, took his wife to Europe for her health. The couple kept meaning to return, but didn't get around to it for decades. Sargent was bom in Florence in 1856, and didn't see his homeland until he was almost twenty. His parents were nomads, constantly moving to stay warm in the winter and cool in the summer. They were not wealthy, not particularly social, and they lived in constant fear of ill health. Sargent had few friends and almost no official schooling.

The traveling gave him an easy command of French, English, Italian, and German. The expatriate American community, in turn, was rich in both eccentrics and affectations. Not surprisingly, Sargent became a cosmopolitan, at home everywhere and nowhere. He developed a kind of mirrored surface. He was unfailingly modest and shy, but people were rarely sure what he thought; some wondered whether there was anything beneath the surface. He seldom said much of great interest, often finding himself unable to locate the right word, and punctuating his sentences when talking to strangers with an "erer-er-er.

What he had was a magnificent fluency with the brush. In his early twenties, he studied with the flashy society painter Carolus-Duran, and not only was accepted by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris but also

placed second in the matriculation examination there. Afterhis

great success with El Jaleo at the Salon, he had a small setback. Critics gasped in happy horror at his racy portrait of "Madame X," a notorious and busty Parisian social climber with a dropdead profile. The outcry was probably good for business. It bothered him, though, and prepared the way for his move in 1884 to London, where he developed his classic portrait style.

Sargent was the last artist able to endow the stylish rich with something akin to grace. His dancing brushwork conveyed not only the rustling of silk but also the spirit of offhand ease dear to aristocratic taste. He did not tease the secrets out of faces. That would have been prying. In matters of flattery he had nearperfect pitch. He would enhance someone's appearance, for example, but never too much—not so that the sitter would have to acknowledge that he or she needed the help. He was exceedingly polite, and encouraged visitors to come to the studio so that his sit-

ters would not get bored. He soon became so popular among the upper crust that the English painter Walter Sickert complained of "Sargentolatry. ' ' That other great American expatriate, Henry James, adored Sargent. The writer constantly praised the painter both in conversation and in print. The rich social surface of Sargent's work, the artist's fluency, Anglophilia, and appreciation of manners— all these were catnip to a man like James. Yet it was James who, I think, first sensed the mysterious weakness. "Yes," he wrote a friend, "I have always thought Sargent a great painter. He would be greater still if he had one or two little things he hasn't—but he will do. "

What were those little things? James himself was obsessed with the inability of aesthetes to experience the world in its fullness. He must have sensed that Sargent's failure to grasp the world robbed his art of grit and complication. Sargent, who died in 1925, never married, apparently never fell in love. (His closest friend was his sister.) Nor did he seem to conceal any private passions. "No one who knew him well or slightly has ever been tempted to suggest anything whatever about his private life," wrote Stanley Olson, a recent biographer of the artist. And yet one knows from the art that Sargent had the potential for passion.

In one way, El Jaleo is a picture about eruptions. The darks are thunderous. The light flashes. A tornado-like shadow rises from the dancer's head. Her skirts, thanks to the artist's quick brush, tremble in the light. Her pointed fingers make a marvelous, exclamatory rhyme with her high heels. In back a man groans, overcome by the dance. A girl in red spontaneously flings up her arms.

In another way, El Jaleo is terribly still. Sargent always keeps us safely apart. The painting reduces us to tourists twice removed, an audience watching another audience watching a dancer. Of course, aesthetes often get their life from the theater. That is their lovely form of melancholy. Here as elsewhere in Sargent's art, his failure makes his success poignant.

Sargent's superficiality is mysterious. It even conveys an important sadness.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now