Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSOUTH OF THE BORDER

A staggering show of Mexican art— backed by President Carlos Salinas, media jefe Emilio Azcárraga, and poet Octavio Paz— arrives amid much hype, and hope

Art

MARK STEVENS

Mexico must be getting fashionable if Madonna is taking an interest. She already collects the art of Frida Kahlo and apparently wants to portray the Mexican artist on the big screen. Hardly a household name a decade ago, Kahlo is now a widely admired figure, partly because her life embodies so much that people today consider exotic. She was not only a painter but also a political radical, very sexy in the earthy, Mexican way, and married to a great artist, Diego Rivera. She had affairs and she died young.

It's hard not to smile at the thought of Madonna vamping around in Mexican dress-up, trying to convey Kahlo's tragic sense of love and birth. Mexican art is no stranger to kitsch or extravagance, but it is almost always touched with a genuine sense of the sacred or otherworldly. Madonna as a Mexican will probably be about as convincing as Madonna as a Catholic. Yet one can always hope that the Material Girl will grow up—and that the United States will begin to treat Mexico as something more than just hot stuff.

The huge celebration of Mexican culture now at various New York institutions represents an attempt to convey a richer image of the country. Like the convergence of Madonna and Kahlo, there is inevitably something suspect about it; art is being used yet again for public relations. At the same time, the image of Mexico is something that people are now struggling over, in profound as well as trivial respects. Increasingly Hispanic itself, the United States knows shockingly little about Mexico, a nation that may one day be more important to it than any country in Europe. Mexican art offers Americans a fundamentally different picture of the world, a way not only to learn about a neighbor but also to glimpse, like a passing shadow, values long lost here. In Mexicans, there is often an edge of angry pleading to look beyond the stereotypes, to see the world to the south.

The Mexicans are themselves now undergoing a soul-twisting reappraisal, trying to shed the weight of an ossified revolution and, like the Soviet Union, find a formula for renewal. Just as the U.S. must learn more about Mexico, so Mexico now seems obsessed with what it means to be Mexican—with finding an image that works in the modem world.

'Mexico: Splendors of Thirty Centuries," opening this month at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, begins with the art of the pre-Columbians, continues through the decorative work and painting of the Spanish colonial era, and includes the great muralists of the revolutionary period —Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros. A number of smaller shows will enrich the picture. The Americas Society and the IBM Gallery will present later Mexican art, and a consortium of Mexican galleries will show contemporary work in SoHo. An exhibition of work by women artists will be at the National Academy of Design, and the International Center of Photography will show Mexican photography.

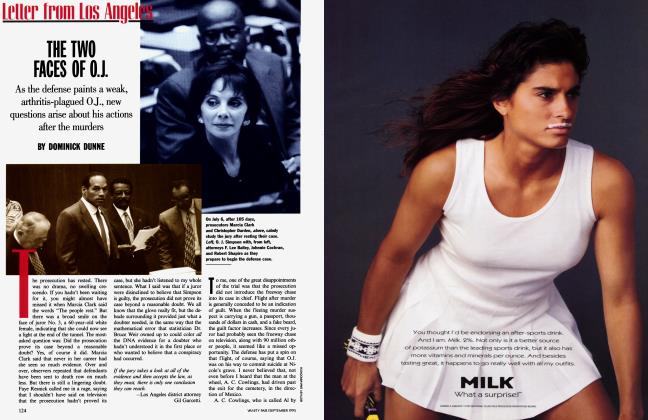

The exhibition at the Met is the centerpiece. Three Mexicans in particular stand behind it like presiding "angels." Each is deeply concerned with forming the country's image, but each from a different standpoint. Two of them are men of affairs; one is a poet.

The principal instigator and backer of the Metropolitan exhibition is Emilio Azcarraga Jr., perhaps the richest and (after the president) most powerful man in Mexico. Azcarraga has a natural interest in the power of an image; he is the principal shareholder in Televisa, which owns almost all the television stations in Mexico. Like many masters of the media, Azcarraga maintains a fairly low profile, but has made it clear through various surrogates—including his wife, Paula C. de Azcarraga—that the image of Mexico abroad exasperates him (drugs, corruption, immigrants, earthquakes, and so on). About five years ago, well before the election of the reform-minded, Harvard-trained president, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, Azcarraga began promoting the idea of a show that would celebrate another side of Mexico. "We saw that the country needed a face-lift internationally," says his wife. "We felt badly treated presswise all over the world. . . . We have here a social life, a private enterprise, that was marvelous in sustaining life through all the difficult times. But it was forgotten.

' 'Art is a good way to remind people of other aspects of the country," says Mrs. Azcarraga. "We have had ups and downs, revolutions and all that, but there was always an exceptional art life. Something coherent and traditional." In today's world, contemporary art can also promote a country's image, and the Azcarragas have helped found the Centro Cultural Arte Contemporaneo in Mexico City.

Carlos Salinas is the exhibition's second angel. Like Francois Mitterrand of France, he is a politician who actually seems interested in artists and intellectuals; it appears likely that he has even read a book. A technocrat in search of a vision, he immediately saw that an exhibition like the Met's would serve the intention of his government to enhance Mexico's image, thereby attracting American investment. Expecting little more than an official handshake, representatives of the Met visited Salinas at the presidential palace in Mexico City to win his support for the project, which had been plagued by bureaucratic snafus and the reluctance of some communities to lend objects.

"We brought four or five catalogues wrapped as presents, which we plunked at the head of the table," said one Met official. "He looked at the pile and the first thing he said was 'Which one is the Degas catalogue?' We figured we would have fifteen minutes and instead had an hour." He kept asking Met officials, "What do you need? What can we do for you?" "He regarded this show and the related activities as really pivotal to getting American support for Mexico," says the official.

If Azcarraga represents Mexican business, and Salinas the Mexican government, the poet Octavio Paz, the third angel behind the Metropolitan show, represents Mexican culture. In a way Paz is the most important, for Azcarraga and Salinas, despite their power, inevitably arouse the suspicion that their interests do not go much beyond public relations, since both obviously want to move Mexico closer to the U.S. and the modem world.

Paz's position is more complex. Now in his seventies, the acclaimed poet and author is a presiding figure in Mexican culture, a man with an almost priestly function in that he is looked to as a kind of intercessor between the spirit of Mexico's past and its current predicament. The Met's catalogue will be an enormous tome that few will read, Paz's essay being the exception. In viewing three thousand years of Mexican art, Paz believes, "an attentive and loving eye will perceive, in this diversity of works and epochs, a certain continuity. Not the continuity of a style or an idea, but something more profound and less definable: a sensibility.''

Paz is far too cagey a poet, and much too allusive a writer, to define that sensibility with crimping precision. But he naturally locates its roots in the civilizations of Mesoamerica, which, unlike European cultures, evolved in utter isolation. Like that of an island cut off, the nature of the life in pre-Columbian America became unique to the place and, compared with the world of outsiders, infinitely strange.

Paz immediately identifies the strangeness, the "sacred horror," of these civilizations as the source of their hold on us. "We glimpse through their complicated forms a buried part of our own being." Of course, the practice of human sacrifice is a critical part of the fascination they hold for us. On one level, the fascination is a cheap ticket; what arouses a chill of adult recognition, however, is that the sacrifice is not trivial, nothing like the show-biz murder of gladiators.

"The Mesoamerican peoples... believed that the universe is in eternal danger of stopping, and thus perishing," Paz writes. "To avoid this catastrophe many must nourish the sun with. . . blood." Their culture was profoundly religious, with marvelous creation myths. Of course, much of the mystery cannot be transported to the Met—above all, the frightening majesty and scale of the architecture. But the ferocity of form in Mesoamerican sculpture is well represented. There are few conceptions more beautiful, and more chilling, than the feathered serpent, a creature that seems to coil together earth and sky.

It was a shock to the Indians to discover that there were other people and other gods in the world. "They could not consider the Spanish," Paz says. "They did not fit their mental categories." He goes on to say, "One can only imagine the despair of the Aztecs when. . . their chieftains and priests decided to send against the invaders, as a last desperate measure, a fire serpent capable of consuming the world in flames. This enormous paper 'magical' serpent, the 'divine weapon' . .. was immediately demolished by the two-handed swords of the Spanish."

The legendary fatalism of the Mexicans may owe something to that terrible rupture of belief. The surge of Spanish missionaries and colonists into Mexico offered the Indians a new religion, Catholicism, which they took to with the passion of an orphan for his adoptive mother—and there began the astonishing amalgam of pre-Columbian and European ideas and forms, the result of which takes up most of the Met exhibition. Mexico may share a continent with the United States, but its roots in Indian myth and Counter-Reformation Catholicism make it, as Alan Riding suggested

* in his recent book about Mexico, a distant neighbor.

What intrigues me about Mexican art, beginning with the pre-Columbians but continuing thereafter, is the unending insistence upon a world that is spiritually governed. Mexican art moves through the cycles of European art in its own idiosyncratic way, usually making what it inherits otherworldly. For example, Mexicans used the Baroque and Rococo not just to dazzle the eye or to displace conventional reality but to catapult the mind into a simulacrum of heaven. Mexican art pushes against boundaries, insists on being too much, embraces kitsch, displays a feeling for color that does not stoop to good taste. Art as just art is never enough.

In the making of the Metropolitan show, there were many arguments—above all, about how to end it. The Mexicans naturally wanted the museum to present some recent art, but deciding whom to include proved difficult. Finally, the decision was made to show no artist bom after 1910. But the difficulty in ending the show is meaningful in itself, for the ending is not clear, and the effort to create an image of Mexico that includes the present will leave anybody who thinks about it full of questions. If the force of Mexican art is to recover some buried part of our being, some imaginative need unmet in contemporary culture, one has to wonder if this sensibility can survive in a Mexico that is trying to modernize.

For example, the Televisa of Emilio Azcarraga will rightly take pride in the powerful image of Mexican art, but modem television usually inevitably subverts and weakens local traditions, smooths out eccentric concerns and spiritual quirks, celebrates surface blandness over what lies buried. The foreign investment so coveted by President Salinas may help alleviate what Paz calls the "urban leprosy" that afflicts Mexican cities, but it will also make the country increasingly like other places, less "strange" in the way admired by the poet. As the Mexicans slowly become more American and Americans slowly learn about Mexico, will the sensibility celebrated in the Met exhibition survive as anything other than a self-conscious manipulation of earlier manners or a raid on past passion? If Madonna decides to play Frida, she might spend some time trying to answer that question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now