Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHow Nixon Came In from the Cold

It wasn't good-bye but au revoir after all. With vintage Nixonian audacity, the disgraced former president has completed his political rehabilitation just in time for the twentieth anniversary of Watergate. MICHAEL R. BESCHLOSS reveals how Richard Nixon began maneuvering just weeks after his resignation to arrive at this moment, when George Bush publicly hails him as "one of the greatest statesmen of the twentieth century"

MICHAEL R. BESCHLOSS

On an icy day in February, sitting by a gas fireplace in his yellow New Jersey dining room, Richard Milhous Nixon is poised for the best month of his life since his landslide re-election in November 1972. Two weeks hence, he will send out a five-page memo to dozens of Washington opinion-makers complaining that the Bush administration's aid to Boris Yeltsin's Russia is "pathetically inadequate." Carefully leaked to major news media, this document will restore him to the center of the national foreign-policy stage. Despite the direct attack on his leadership, George Bush will become the first president since Watergate to appear with Nixon on a Washington dais, hailing him as "one of the greatest statesmen of the twentieth century."

Today, Nixon is just back from a few days' rest at the sunny 18,000-acre estate near Manzanillo, Mexico, of his friend the British financier Sir James Goldsmith, who had the former president flown down on one of his private planes. Nixon's face is lean and pink, the liquid brown eyes preternaturally clear and alert. He looks a decade younger than his age. His voice is thicker and raspier than during his heyday. When he peers down, a ray of sunlight falls across the crown of his head. His hair appears finer and straighter, almost silver-blue.

A smiling German woman from the Harz Mountains serves an elegant French luncheon and white-chocolate dessert. When his visitor does not eat with sufficient relish, Nixon gibes, "Obviously you don't like the food. O.K., we can send out to McDonald's!" A subtle Bordeaux is served, but Nixon does not indulge his well-trained palate. He explains that two years ago in Miami he suffered a heart disturbance. His doctor told him that wine would shorten his life, so he gave away most of his large and excellent cellar to family and friends.

Nixon soon turns to more worldly subjects, speaking first about George Bush. He notes that Bush, like most presidents, is not prone to asking outsiders for serious advice:

Nixon lambasted Bush for "weakness": "I don't understand what happened to George."

"He likes to run his own show." The former president says that "Bush calls me on birthday and wedding anniversaries. I get those nice, handwritten notes. It's hard to see how he finds the time for anything else!"

His history with Bush is mixed. In August 1974, on the day after Nixon's final Cabinet meeting, Bush, then Republican national chairman, wrote him of his "considered judgment that you should resign." During Bush's vice presidency, Nixon privately lambasted him for "weakness." He recalled that Bush's father, Senator Prescott Bush of Connecticut, had been "ramrod-erect" and "tough as nails": "I don't understand what happened to George."

Now whatever differences they have are gentlemanly: "Bush, far more than I, believes in the effectiveness of personal diplomacy. He believes that if you have a good personal relationship, it helps on substance. I believe that unless leaders' interests are compatible, a personal relationship doesn't mean anything."

Nixon says that Ronald Reagan was similar: "I remember watching Reagan and Gorbachev on television in Red Square—the body language. Reagan put his arm on Gorbachev's shoulder. Gorbachev was not comfortable with that kind of thing. Neither was I. Eisenhower was the same way. ' '

Nixon was frustrated by Bush's slowness to abandon Gorbachev for Boris Yeltsin: "Being the gentleman that he is, he does not like to throw over his old friends. ' ' Darting to another subject, he doubts that the president will get much benefit in the 1992 election for his victory over Iraq: "Whatever publisher paid General Schwarzkopf all that money is going to lose it. Americans have forgotten all about the Gulf War."

He is appalled that, in 1992, voters seem to believe that foreign policy no longer matters: "People are saying, 'Why spend $5 billion on Russia when we've got to put a new cesspool in Winnetka?' " Tapping the table for emphasis, Nixon warns that without help "democracy could fail in Russia." He says, "I don't think Boris Yeltsin is the Second Coming. As Churchill said in Great Contemporaries, 'He bums all of his candles at both ends.' He's compulsive. I give him only slightly more than a 50 percent chance to succeed. But he's got guts."

A year and a half ago, Nixon sold his modern, fifteen-room house in Saddle River, New Jersey, for $2.4 million (to a Japanese businessman, inevitably) and purchased the end unit of a modest row of gray mock-Tudor town houses in a new, nearby housing development. Separated from an industrial site by a fringe of trees, the three-bedroom home is the smallest space in which Richard and Pat Nixon have lived for more than forty years—no minor consideration for a seventy-nine-year-old man and an eighty-year-old woman of uncertain health.

Eighteen years after resigning to avoid impeachment and removal from office, the thirty-seventh president of the United States rises while it is still dark, dons a suit and tie, and strolls for two miles. A neighbor's Shih Tzu often runs out to greet him. Nixon says that some of his best lines come to him while walking alone.

He spends much of the day in the loft-library his wife designed for him. Sitting near a large globe, he telephones around the world. The irregular-shaped room is floodlit by skylights punched in the vaulted ceiling. Its walls are encased in custom-made nut-brown cabinetry—shelf after shelf of books. Nixon's library is heavy on Winston Churchill and Abraham Lincoln (not only Sandburg's heroic life but Vidal's acerbic novel). It includes the Public Papers of U.S. presidents through August 1974, as well as Paul Johnson's Modern Times, which Nixon admires extravagantly. A life of Pepys and David McCullough's Brave Companions were sent to him recently by New York senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who as a Nixon White House aide had once famously prodded his boss to read a life of Disraeli.

When he writes, he sits down at a French Provincial writing table that resembles Charles de Gaulle's, adorned by a statuette of miniature elephants on parade, trunk-to-tail. He slips on a pair of black-rimmed reading glasses with a piece of transparent tape wrapped around the left temple.

Every weekday, Nixon is driven to his suite in a nearby Italianate office building that exhibits a copy of Michelangelo's David in the lobby and whose major tenant is a travel agency.

Nixon's almost donnish existence is easily the most tranquil period of his life, the embodiment of his grandmother's Quaker term "peace at the center." It is very different from the commanding place in American politics and society that he once envisioned for himself.

In January 1973, the re-elected president sat down at the writing table in his home office at Key Biscayne and scrawled on a legal pad, "Goals for 2d term." He planned to root Kennedy-Johnson holdovers and other potential disloyalists out of the federal bureaucracy and permanently transform the structure of the Cabinet departments.

He would position John B. Connally, L.B.J. intimate, former Democratic governor of Texas, and his own surprise first-term secretary of the Treasury, to be the thirty-eighth president of the United States. After Connally announced his jump to the Republicans, Nixon hoped, he would be followed by millions of other Tory Democrats estranged from the party of George McGovern, ultimately making the Republicans the majority party. Inaugurated in 1977, President Connally would owe his predecessor more than any other president of the century. From La Casa Pacifica, Nixon's cliffside "Western White House" in San Clemente, the former president would serve as a kind of philosopher-king.

Nixon's institutional radicalism did not end with politics. On the legal pad, he also scrawled, "New Establishment— Press—Intellectuals—Business—Social—Arts." He planned to use his network of wealthy allies and friendly foundations to write his own version of Debrett's Peerage—a new power structure to supplant the "fashionable negativism" of the northeastern, Kennedy-oriented establishment that had "paralyzed" the nation with "self-doubt and second thoughts."

That same January, Nixon's domestic counselor John Ehrlichman advised a trustee of the Nixon Foundation—conceived as the engine room of Nixon's post-presidential life— that when Nixon retired he did not intend to be a lawyer, executive, or depend on money from book advances under strict deadlines. Instead, the president planned to rent his papers and memorabilia to the Nixon Foundation for $200,000 a year, the equivalent of his White House salary.

All of these dreams were shattered within two months. The same spring he had planned to spend grooming Connally, Nixon instead immersed himself in the Watergate defense. When Connally changed parties, few noticed.

In August 1974, Nixon was exiled to San Clemente. Two weeks before, Connally had been indicted for perjury, obstructing justice, and accepting bribes. (He was acquitted.) Republicans were thunderously defeated in the 1974 congressional elections. Their elders resolved that Nixon not be mentioned at their 1976 convention. The Nixon Foundation was disbanded.

Several days later, someone tossed a firebomb into Pat Nixon's childhood home in Cerritos, California. When the former First Lady ventured out of La Casa Pacifica, someone spat on her. Visitors to Madame Tussaud's in London voted Nixon the most "hated and feared" figure in the waxworks.

Kichard Nixon resolutely denies that since Watergate he has engaged in any kind of "deliberate" effort to regain full membership in the American political family. But in private his advisers speak of his campaign for a "final comeback." They note that within a fortnight of leaving the White House, Nixon was already asking friends for advice on restoring his public stature. They suggested that any return to favor would rest on public recognition of his foreign-policy skills, conveyed through books, articles, speeches, and confidential advice to those in power.

The first step was a flight to Beijing in February 1976 for the fourth anniversary of his fabled rapprochement with China. Arriving three days before the New Hampshire presidential primary, the beaming former president appeared on every U.S. front page and news program. Fighting with Ronald Reagan for his political life, President Gerald Ford was irate: Nixon's act would remind voters of the man who had chosen Ford for national office and been pardoned by him.

At the White House, shaking his head, Vice President Nelson A. Rockefeller told his longtime adviser James M. Cannon, who was serving as Ford's domestic chief, "You know why he went? He's bringing back a shipment of gold for himself." Cannon, amazed, asked, "How do you know that?" Rockefeller said he had heard it from an eminent New York banker.

Cannon immediately called a White House lawyer, Richard Parsons: "Hey, look, the vice president told me this. Should we tell somebody?" Parsons replied, "You're an officer of the U.S. government. You know what the answer to that question is." Cannon confided the rumor to Ford's White House counsel, Philip Buchen, a polio victim. By Cannon's account, Buchen "almost came up out of his chair." Without involving the president, Buchen asked U.S. Customs and the Secret Service to investigate the allegation. (No evidence of wrongdoing was found.)

Dogged by this kind of rumor for years, Nixon as expresident has striven to demonstrate himself cleaner than Caesar's wife. When he makes a speech, he accepts no honorarium and often pays all expenses for himself and his entourage. He has refused dozens of lucrative corporate jobs. Chatting with a former Jimmy Carter aide, Nixon praised Carter's decision not to sit on corporate boards—"unlike Jerry Ford." He went on to say he had been told by an industrialist who had generously supported Ford that the man had encountered Ford on a golf course and asked him to stop by his villa and meet his managers. By Nixon's account, Ford had agreed, but only if paid in advance.

In the 1980s, in the spirit of the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act, Nixon reduced the federal salaries of his staff by 5 percent and made up the difference from his own pocket. In 1985, he announced that he was giving up his Secret Service detail to save the U.S. government $3 million a year.

Nixon's critics have suggested that these public-minded gestures, not to mention the large legal expense of fighting the U.S. government to keep certain of his papers closed, could not be sustained by his real-estate investments, government pensions, and book advances.

Court documents reveal that Nixon wrote letters in the mid-1980s to Nicolae Ceausescu of Romania on behalf of his former military aide Colonel Jack Brennan and his onetime attorney general John Mitchell, who were involved in Global Research International, a company that sold military supplies and helicopters to foreign governments. When Global Research wished to sell $181 million worth of Romanian-made uniforms to Iraq, Nixon wrote Ceausescu, "I can assure you that Colonel Brennan and former Attorney General John Mitchell will be responsible and constructive in working on this project with your representatives." In another letter, Nixon wrote the dictator, "I wanted to let you know how highly Mr. Mitchell spoke of the diligence of the Romanian workers."

It would have been in character for Nixon to do a good turn for two men who had gone through fire for him during Watergate and beyond. There is no evidence that Nixon personally benefited from these transactions, and it is unlikely he would have risked jeopardizing his careful efforts for rehabilitation with an act of international financial legerdemain that could easily become public.

Nixon orchestrated dinners with journalists with the precision of a campaign rally.

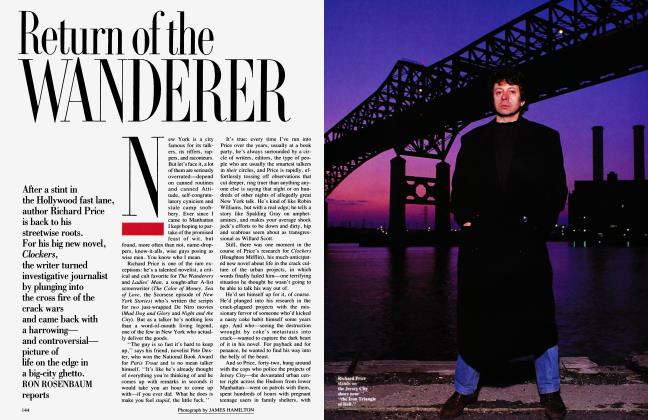

After Nixon's 1962 defeat for governor of California, he moved to New York, enabling him to polish his reputation among national opinion-makers. In February 1980, he did the same thing: he moved to an East Sixty-fifth Street brownstone and shifted his campaign for vindication into high gear.

He had spoken to a Reagan operative, Edward Rollins, about becoming his chef de cabinet, but finally advised him, "Reagan's going to win the presidency. If I were you, I'd want to go make history, not just relive it." After the 1980 election, Nixon consulted his friend Roger Stone, Reagan's young, harddriving campaign manager in the Northeast. (At nineteen, Stone had worked for Nixon's Committee to Re-elect the President, CREEP, and Nixon donated $100 to Stone's victorious 1977 campaign for national Young Republican chairman.) Stone lobbied Nixon to "build relationships with reporters." This was not the most welcome advice to the man who agreed with Paul Johnson's description of Watergate as a "media putsch. '' Stone promised to reach out "very selectively" for "unbiased" younger journalists who had not covered Nixon during Watergate and who would be fascinated to meet the former president. He would focus on those who seemed to have especially promising futures.

Nixon was willing to dine with journalists, but he would not crawl. During a vacation at La Samana on St. Martin, Nixon was dismayed to see his old Watergate nemesis Benjamin Bradlee of The Washington Post, there on vacation with his wife, Sally Quinn. Whimsically, Bradlee got it into his head that Nixon might be ready to "tell all''—and tell it to him. Several times, when he espied the former president strolling down the beach, he rushed out to see him. But Nixon dove into the water and swam in a great half-circle until he had safely circumnavigated Bradlee.

Morton Kondracke of The New Republic, Strobe Talbott and Roger Rosenblatt of Time, Sara Fritz of the Los Angeles Times, Gerald Boyd of The New York Times, and dozens of others were invited for luncheons and dinners at Nixon's New York town house or, when he moved in 1981, the house in Saddle River. When guests flew in from Washington, Nixon orchestrated the event with the precision of a campaign rally—drinks in the living room, dinner in the dining room, liqueurs and coffee in the sun-room, all in time for the guests to make the last shuttle out of LaGuardia. Nixon jovially referred to the sessions as "seances."

His wife was never present. Sequestered in another part of the house or off visiting her grandchildren, Pat Nixon had long since said good-bye to all that. When she resisted sitting for a White House portrait in the late 1970s, her daughter Julie urged her not to give her father's foes "a victory by default." She replied, "Why not? They won, didn't they?"

Before the guests arrived, the former president studied their backgrounds so that he could drop personal references into the conversation. ("You may not remember this since you were born in 1949 but. . . ") Many were surprised by the private charm, alert intelligence, worldliness, and stiletto wit so obscured by Nixon's public caricature. They were intrigued by proximity to the political figure who, more than any other, had presided over their lives. One visitor was struck by the sheer will with which Nixon had overcome his innate bashfulness—first to rise to the top of an extrovert's profession and now to entertain his old enemies, the press: "His eyes fluttered and his face tightened at the slightest interruption, the slightest back talk. There was something so obviously rehearsed, calculating, unspontaneous about the whole thing. We were being played like violins and we knew it."

During the meal, the former president spoke the throwaway lines that his friends always heard and his large audiences did not. On the Italians: "A lousy government but beautiful embassies." On the F.B.I.'s bedroom tapes of Martin Luther King: "L.B.J. and everyone else in Congress got to hear them. I didn't. It's discrimination!" On an Eastern European politician: "A very clever guy—strong and devious, all the things a political leader needs."

Women were underrepresented among Nixon's guests. They would have compelled him to dilute his attempt to be one of the guys. Nixon once said that his 1956 vice-presidential opponent, Senator Estes Kefauver, campaigned "with a Bible in one hand and his cock in the other." On the flagging New York Mets: "I'm pissed. Are you pissed?"

Nixon labored to identify with his visitors. He told two magazine journalists, "You're a couple of intellectuals. I won't try to prove I'm an intellectual. ' ' (One of the two recalls, "With this he semi-inadvertently reminded us of his defensiveness and resentment of the 'Harvards.' ") He commiserated with his fellow writers: "You see, I don't write easily. I'm not a natural writer." He spoke of the "agony of creation."

Occasionally he struck younger guests as someone from another place and time. When men mentioned their wives, he joked, "You still living with them?" When he carped about "the Georgetown salons" and "the Georgetown set," his listeners politely refrained from saying that many of the Kennedy Democrats to whom he referred had moved away, were dead, or at least were no longer a "set."

Visitors were enchanted with his detailed, tough-minded understanding of the American political scene, although as a seer he did not always bat a thousand. In early 1984, he predicted that the Democratic ticket would be Walter Mondale and Gary Hart and that it would run Reagan and Bush a "close race." Through much of the 1980s, Nixon insisted that Democrats should nominate Mario Cuomo. He "didn't buy the stuff" that Cuomo "looks Italian": "This fellow is great in debate. He makes good speeches. . . . The Democrats have lost the South. . . . They've got to go for New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Connecticut. They've got to go for Illinois, Ohio, Michigan, and California. That and a couple of other odds and ends, and they've got it made."

Nixon also kept up his contacts with older journalists. He once told Washington Times editor Amaud de Borchgrave that he had advised President Reagan to nominate de Borchgrave as C.I.A. director. When Nixon published a book, his old aide and speechwriter Patrick J. Buchanan interviewed him on CNN.

It is difficult to find an instance in which a reporter pulled a punch as a result of dining with Nixon, but the seances doubtless caused the press to take Nixon's views on current issues more seriously than had he remained incommunicado in San Clemente. They helped Nixon the contemporary figure to supplant what Nixon himself referred to as "the Watergate man."

The former president was not loath to use the stick as well as the carrot. Nixon's old White House lawyer and friend Richard Moore once gave him what Nixon considered the best advice he'd ever received about the press: "Go after the little lies." No "unfair shot" should go unnoticed.

Thus when the Boston public-television station WGBH asked for help on a Nixon documentary, his staff replied that the day public television treated the former president fairly would be the day that "pigs will fly." When Hugh Sidey wrote in Time of a pair of martini glasses in a photograph of Nixon taken the day before his resignation, a denial flew back.

In 1989, ABC announced its intention to air a docudrama, sponsored by AT&T, based on The Final Days, the bestselling 1976 expose of Nixon's last year in office by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, which, among other things, depicted a lifeless Nixon marriage. Nixon considered this a matter of personal honor: just after reading it, Pat Nixon suffered her first stroke. A Nixon aide wrote the AT&T chairman, Robert E. Allen, "Perhaps you should change your corporate slogan to 'Reach Out and Smear Someone.' " Nixon changed his long-distance service to MCI.

A Nixon lawyer wrote ABC that the film was an "infringement of his right to use his name and image to promote his own writings and statements about foreign policy and other issues facing our nation and the world." ABC News was informed that Nixon would no longer accede to its interview requests. One of its producers called Nixon's staff to argue that The Final Days had been presented by ABC's entertainment division, not News, but to no avail. (Nixon reversed his decision in January 1992, when he was promoting his ninth book, Seize the Moment, and agreed to be interviewed on Nightline by Ted Koppel.)

Nixon knew the value of good relations with a sitting president. He recalled that after Franklin Roosevelt's death Harry Truman had invited Herbert Hoover to the Oval Office for his first visit since 1933. Afterward, Hoover groused that maybe now those who had smeared him for twelve years as the villain of the "Hoover Depression" would feel somewhat cowed.

Even after leaving the White House, Ford kept his distance from Nixon, desiring to avoid the appearance of collusion behind the Nixon pardon. Nixon's relations with Jimmy Carter were glacial. In 1979, Carter invited him to a White House dinner for the Chinese vice-premier, Deng Xiaoping. But, Carter was informed, Nixon was privately contemptuous of Carter's country affectations and his "softness" in dealing with the Soviet Union, Iran, and Nicaragua.

During the 1980 campaign, Nixon sent secret memos on strategy and tactics to Rollins and Stone, quizzing them about power shifts within the Reagan caravan: "What's your read on this guy?" After Reagan's election, Nixon did not jeopardize his new access to the Oval Office by appearing at the inauguration or asking for a formal job. He knew that even if Reagan gave him no public role those who had plagued him for six years might now feel somewhat cowed.

He praised Reagan publicly, but during his seances with journalists he said he was dismayed by the new president's belligerence toward the Soviet Union and his obeisance to the Republican right: "You have to have them with you, but you can't let them dominate you." Nixon said he disagreed with Reagan's view that if government tackled a problem it would "screw it up." As for substance, Reagan could "talk an hour and a half and not say a hell of a lot."

(Continued on page 148)

(Continued from page 119)

Nixon's private criticism of Reagan from the left in the early 1980s was important in winning over many of those who had once been most opposed to him. By exalting Nixon, they could whipsaw Reagan: compared with the new president, Nixon seemed refreshingly reasonable and moderate, not to mention his private sagaciousness and superior intellect.

Among liberal journalists, he argued that his conservative label was something of a misnomer: witness the openings to the Soviet Union and China, his first-term domestic programs, and his indifference to the Reaganites' litmustest issues such as gun control and abortion. Nixon now privately referred to himself as a "progressive" Republican: the word "moderate" suggested "that you don't believe in anything, that you just want to be on the go for what works, and I don't agree with that. I think you've got to have some beliefs and then make it work."

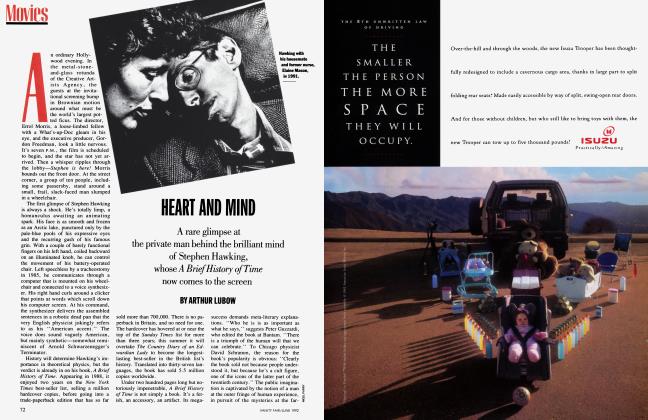

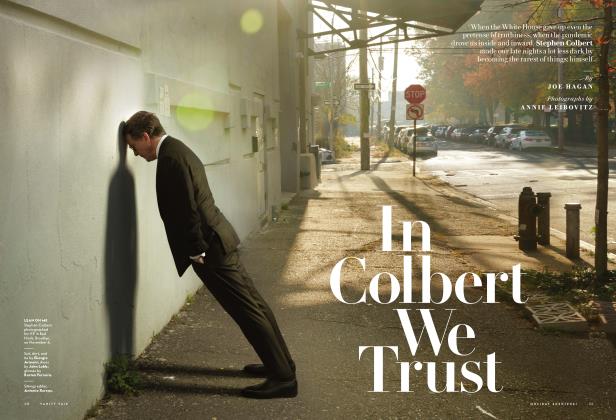

In the fall of 1978, Nixon had gone to Paris and Oxford, where he spoke before the Oxford Union. In May 1984, he made his first major Washington appearance since resigning—a foreign-policy speech to the American Society of Newspaper Editors that was a great success. Fred Bruning of Newsday observed, "Here was a man only two years younger than Ronald Reagan who did not lose his way in mid-sentence or appear suddenly to lapse into private reverie." Anthony Lewis of The New York Times was not so charmed: "We forget so quickly in this country. And we have forgotten this man's endless offenses, petty and grand, against decency."

In San Francisco two years later, the American Newspaper Publishers Association gave Nixon a standing ovation. Asked about the lessons of Watergate, he evoked friendly laughter: "Just destroy all the tapes!" Katharine Graham of The Washington Post shook his hand for photographers and suggested to her Newsweek editors that they consider a story on Nixon's rehabilitation. When they duly asked Nixon for what was then a rare interview, Roger Stone laid down the ground rules: no questions on certain subjects, no tape recorder, no photographs inside the Nixon house—and Nixon must get the cover. Stone considered the result a "milestone" in Nixon's resurgence: in May 1986, the smiling former president appeared on the cover of Newsweek with the headline "He's Back: The Rehabilitation of Richard Nixon."

That year Ronald Reagan made his own surprise contribution to Nixon's rehabilitation: the Iran-contra affair. Nixon had encouraged Victor Lasky (JFK: The Man and the Myth) to write a book showing that he was not the first president to use tough methods. Lasky's It Didn't Start with Watergate was a national bestseller in 1977. For Nixon's partisans, Iran-contra showed that it didn't end with Watergate either. Some said that compared with the Reagan administration's subversion of congressional authority, Nixon's obstruction of justice seemed small potatoes. Others reasoned that Reagan had been spared Nixon's fate only because he was far more popular on Capitol Hill and because Congress lacked the stomach for another impeachment drive.

Reagan called Nixon for advice on how to handle the gathering storm. During Watergate, Nixon had tried to save himself by seeming indispensable in foreign relations. He advised Reagan to make a new push for a Soviet-U.S. summit and arms treaty in 1987. "It is not going to be another Watergate, as long as you stay ahead of the curve." He told Reagan to fire two or three of the people involved and then "change the subject."

On Watergate, Nixon pursued his own revisionism. In his 1990 book, In the Arena: A Memoir of Victory, Defeat, and Renewal, he suggested that the scandal was an outgrowth of the extraordinary measures he had had to take as president of a country at war both at home and in Vietnam. He wrote that his "central mistake" was "not taking a higher road than my predecessors and my adversaries."

Privately, Nixon gives some weight to his wife's suspicion that he may have been done in by some kind of intelligence conspiracy. He wonders whether he resigned too soon. Close friends and members of his family feel that White House aides, after nineteen brutal months of Watergate, were too eager to escape from their own ordeal and their suggestion that he resign was based more on exhaustion than on rational calculation of Nixon's ability to fight on.

The former president has long believed that history is only "ripe" after fifty years. By then, he hopes, Watergate will be a historical "footnote." From the day of his resignation, he has worked to advance this aim by careful shaping of the historical record. He demanded that his presidential papers and four thousand hours of secretly recorded White House tapes be sent to him immediately. Gerald Ford's lawyers made a deal: the collection would be shipped to a National Archives center in California. Nixon's people would hold one key, Ford's the other. After five years, Nixon could destroy the entire archive, if he wished.

The deal was announced at the moment Ford pardoned Nixon. An outraged Congress repealed it and ordered the National Archives to impound the entire collection. Appeals by Nixon's lawyers to restore some version of the Ford agreement failed. Partially open, the collection now resides in an Alexandria, Virginia, warehouse.

During Nixon's first eclipse, in the 1960s, he grandiloquently compared himself to his heroes Winston Churchill and Charles de Gaulle, who had had their own spells in the "wilderness." (He briefly thought of writing a book about statesmen who had fought their way back.) In the 1980s, he presented himself as the guru of renewal. Nixon felt that Americans were "crazy" about the word. When he started to write In the Arena, he said that if he could let people see what he had been through and that he had recovered "at least in part," that might tell them that life wasn't over.

The result is a self-help guide for the defeated. Nixon's prescription is to think on a large scale. In private, he lampoons those who contemplate their own navels: "How do I feel about myself? Do I like myself? The media has a lot of it. . . . Instead of looking in the mirror, they ought to be looking out the window.

. . . Unless you have goals beyond yourself, you're not going to live up to your capacity, and you're going to age prematurely."

The theme of renewal dominates the Richard Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, California, opened by Nixon, Ford, Reagan, and Bush in July 1990 with brass bands and ceremony. Before touring the exhibition hall, visitors sit down in an "orientation theater" to watch a biographical film. (One Nixon Library official says, "If this doesn't erase any antiNixon sentiments in them, nothing will.") At the start, the narrator speaks of Nixon's "remarkable recovery" since 1974, his "astonishing renewal," the "new appreciation" of his "lasting achievements." Flashing back to 1947, the voice tells us that friends warned the young congressman that the Alger Hiss case would min him, "but he wouldn't give up." After he was defeated in 1962, "everyone thought he was through," but "hard work, careful planning, and shrewd instincts brought him back from oblivion."

The motion picture includes an excerpt from Nixon's tearful farewell to his staff before leaving the White House by helicopter. (When the president declares onscreen, "It is only a beginning, always," a choked-up Yorba Linda tourist cries out, "It's true!") The narrator goes on, "He was in his deepest valley, but he would not stay there for long." Images flash onto the screen of Nixon's meetings with foreign leaders, the Newsweek cover.

At the end of the film, Nixon stares into the camera: "What advice do I have for young people? Never, never give up. ... If you take no risks, you will suffer no defeats. But if you take no risks, you will have no victories."

In retirement, Nixon has periodically honored the more compassionate side of his nature that moved him while president to write Hubert Humphrey after he lost the 1972 nomination and to call Edward Kennedy's namesake son when he lost a leg to cancer. Aside from the charity of the gesture, he knew this kind of thing would soften his old reputation for relentlessness toward enemies. He sent his books Real Peace and Leaders with friendly notes to George McGovern, whom he had once reviled for equating him with Hitler. In January 1984, while running again for the Democratic presidential nomination, McGovern called on Nixon in New York. Nixon praised his old foe for saying what he believed "rather than pleasing the crowd."

Another old rival with whom Nixon's relationship grew warmer with each retelling was John F. Kennedy. After Kennedy's murder, some schoolchildren who remembered the 1960 televised debates thought of Nixon as "President Kennedy's friend." Linked forever to Kennedy in the public mind, Nixon endowed their often bitter contest with elements of romantic legend. Before audiences, he noted that when "Jack Kennedy and I" arrived in Congress in 1947 both endorsed a bipartisan foreign policy. The Nixon Library displays the two men's correspondence under the heading "RN and JFK: Friendly Rivals."

After years of noncommunication, the former president began sending copies of his books to figures like his C.I.A. director, Richard Helms, and John Ehrlichman, who presumably know stories that would not enhance the record of the thirty-seventh presidency. Nixon also kept up with John Connally, who ultimately fell not through political scandal but through personal bankruptcy. He is inspired by Connally's "irrepressible, optimistic attitude" and the stout support of his wife, Nellie. The lesson of Connally's travails? "Never sign a note for a friend."

Like Garbo, Nixon has always understood the benefits of public mystery, telling aides, "People want what they can't get." He points to Gerald Ford as a perfect example of a former president overexposed. According to Roger Stone, after Jeane Kirkpatrick left the U.N., Nixon advised her, "Don't accept every invitation. Don't answer every press call. Don't grant every interview. Reserve your comments for a time when you have something important to say, and you'll find that they clamor for your views."

For Nixon, one corollary of this rule is to make a virtue of the fact that he is not just another ex-president. Watergate has endowed him with a mystique that would be absent had he finished off his two terms without incident. Knowing this, he has striven to preserve his singularity. In 1985, the Reagan staff made noises about bringing Nixon, Ford, and Carter to the White House to advise the president before his first summit with Mikhail Gorbachev. Cagily, Nixon had his staff find out which dates Carter and Ford would be unavailable. Then he offered those dates as the only ones on which he could come to Washington.

But like the man who wants to join any club that would not have him as a member, Nixon grows indignant when he feels excluded. In 1988, Ford and Carter created a blue-chip panel to draft policy recommendations for the next president under the title "The American Agenda." Some of the Democratic members said that they would bolt if Nixon were invited to join. A rule was instantly invented: the commission would include only the two expresidents most recently in office. After George Bush's election, the report was ready. Ford asked, "Don't you think we should send a copy to Nixon?" The document went to New Jersey. A vituperative letter came back from a Nixon aide denouncing the exclusion of the president most noted for his foreign policy. Brent Scowcroft, a panel member who had once served on Nixon's staff, read it and chuckled, "No doubt about it! They're Nixon's words."

Hoping that their report would be widely publicized, Ford and Carter delivered it to Bush at the White House. But Nixon had the last laugh. He chose the same day to call on vice president-elect Dan Quayle. That evening's news was dominated not by Bush's meeting with Ford and Carter but by Nixon's encounter with Quayle.

In 1988, Nixon knew better than to test his public acceptance by asking to speak to the Republican National Convention. He wrote party managers that he was "declining all invitations for political appearances this year. ' '

George Bush was virtually Nixon's last choice for president. After Bush's election, Nixon remained an offstage presence. At a private dinner in December 1989, the Democratic lawyer Robert S. Strauss (now ambassador to Moscow) asked Nixon what Bush should do about General Manuel Noriega. Nixon, who did not know that American troops were already flying toward Panama City, said, "The way I look at Noriega, he's a pimple. It's very ugly and very irritating, but in removing the pimple we don't want to leave a scar, a permanent scar on the body of Central America."

After the invasion, Nixon cautioned U.S. officials to think seriously before doing it again. He compared Bush's expulsion of Noriega to Kennedy's role in deposing Ngo Dinh Diem in Saigon: once the United States changed the leadership of another country it had to take "responsibility for what happens."

When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, Nixon was privately skeptical that Bush could persuade the country and the Congress to go to war. As Bush labored to push twelve resolutions through the U.N., Nixon was impressed with the president's horse-trading skills, but baffled that he would spend so much time and political credit to ensure that world opinion viewed a Persian Gulf war as just. He worried about Bush's sensitivity to polls and the media. Ruefully, he noted that Bush had "five televisions'' in the study in his second-floor private quarters. At least, he said, this was better than L.B.J., who had them "even in the bathroom.''

In December 1990, Bush called Nixon to report that he was considering military action against Saddam. On Christmas Day, Nixon finished a twenty-six-page memo to the president. According to a White House aide, it praised Bush for his handling of the crisis and endorsed the use of force, if necessary. One problem Nixon perceived was that since Saddam Hussein was a "bullshitter" who issued hollow threats, he assumed the same of other world leaders.

In March 1991, Nixon traveled to Moscow, along with Nixon Library director John H. Taylor and Dimitri Simes of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Simes was a Soviet foreign-policy expert who had emigrated to the United States during Nixon's presidency. When he wrote a Christian Science Monitor article in 1982 praising Nixon's courage and integrity, Nixon wrote him a thank-you note saying that Simes's liberal Carnegie colleagues would probably not be very happy with it. Not long after Gorbachev's ascension, in 1985, Simes called on Nixon at his suite in the One Washington Circle hotel (which, as one Nixon friend has noted, is equidistant from the White House and the Watergate complex). Nixon doubted that the new Soviet leader would "go all the way" and shed the Communist Party. He was impressed by Gorbachev's style, "but one shouldn't judge leaders by style."

During a later visit to Nixon's New York office, Simes was concerned about catching the 3:30 shuttle back to Washington. Nixon said, "Don't worry. You still have twenty minutes. My driver will take you." Simes was astonished when Nixon rode along with him to the airport to avoid breaking off their conversation.

In Moscow, Nixon called on hard-line K.G.B. chairman Vladimir Kryuchkov, who told him, "We have had as much democratization as we can stomach." Kryuchkov said that there was still a fundamental conflict between American and Soviet interests around the world. (At that moment Kryuchkov was pondering the coup against Gorbachev.)

When Nixon saw Gorbachev, he was startled by the transformation since their first Moscow meeting, in 1986. The Soviet leader seemed discouraged, defensive, exhausted. Gorbachev insisted that despite his moves toward a hard line he was still a reformer. Citing the old talk about a "new Nixon," he said he was still "the old Gorbachev."

Nixon was not convinced. At a private White House luncheon with Bush, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney, and other foreign-policy officials, Nixon conceded that Boris Yeltsin was "not as smart" as Gorbachev, "not as polished," but insisted that the Russian leader was more durably committed to democratic values. Three months later, for the first time, Yeltsin called on Bush in the Oval Office. After the August coup that spelled the death of the Soviet Union, Simes and Taylor talked to the former president about staging a Nixon Library conference in Washington on new priorities in foreign policy. Perhaps the sessions would one day lead to a new think tank, the Richard Nixon Center. Nixon gave them a green light.

To serve as chairman, Simes recruited his Carnegie colleague James Schlesinger, who was Nixon's last secretary of defense. Schlesinger's history with Nixon was clouded. In 1974, before Nixon's final summit with Leonid Brezhnev, he prodded the president to take a tougher arms-control line. When Nixon said that it had "no chance whatever of being accepted," Schlesinger advised him to use on Brezhnev the same "forensic ability" he had once used on Nikita Khrushchev. Nixon was furious: he felt that had it not been for Watergate Schlesinger would never have issued such an open challenge. During Nixon's final days, when some speculated that the president might pull down the temple around him, Schlesinger ordered that any military command by Nixon be countersigned by the secretary of defense.

The conference was set for mid-March 1992, co-sponsored by the Illinois agricultural-processing firm Archer Daniels Midland. In the circularity of history, A.D.M.'s chief, Dwayne O. Andreas, had given $25,000 in 1972 to Kenneth H. Dahlberg, Nixon's mid western finance chairman. Unknown to Andreas, the money found its way into the hands of the Watergate burglars. Nixon discussed it on the fatal June 23 tape ("Who the hell is Ken Dahlberg?"). Thus, the unwitting agent of Nixon's downfall became the witting agent of his rehabilitation.

Aided by Nixon's old lobbyist friend Robert Keith Gray of Hill and Knowlton, Schlesinger sent out hundreds of invitations to Nixon-administration alumni and much of the foreign-policy establishment, which had once eyed Nixon so warily. Schlesinger wrote to Scowcroft, now White House national-security adviser, asking Bush to deliver the principal address at the Wednesday-night banquet. Plagued by Pat Buchanan's challenge in the early Republican primaries, the president would make no firm commitment. Taylor and Simes raised the matter with Nixon, who was worried about seeming to pressure Bush, or being turned down.

Finally, Nixon's daughter Julie wrote to Bush. On Monday, March 2, the president accepted. Telephones in Simes's and Taylor's offices began ringing off the hook. Bush and Scowcroft assigned Richard Haass of the National Security Council staff to draft a major address.

Nixon planned to return the president's kindness. He invited Patrick Buchanan to his New Jersey office in late March and said, "You and I disagree totally on foreign policy, so let's talk about politics." Nixon told him that his campaign had made its point. It was time to leave Bush alone: "If you want to be a serious candidate in 1996, you're hurting yourself." Buchanan thanked his old chieftain for the advice, but said he would stay in the race.

Someone once observed that when Nixon makes a move, what counts is not where the billiard ball first strikes but the carom. During the same week that Bush agreed to speak at the Nixon Library dinner, Nixon sent out his "confidential" memo charging that American aid to Yeltsin's Russia was "penny ante.. .pathetically inadequate." If Yeltsin failed, people would ask, "Who lost Russia?"

Nixon mailed the memo to friends and foreign-policy analysts across the country. Shrewd to the end, he let it be known that the document had gone out to the fifty people interested in foreign affairs whom he believed most capable of affecting public policy. This gave recipients the sense that they were on Nixon's A list. In fact the memo went out to many more.

The day before the Nixon Library conference, the front page of The New York Times heralded Nixon's break with Bush over aid to the former Soviet republic. The story led three network newscasts. Some in Nixon's circle were aghast. They worried that Bush would perceive the memo as ingratitude at the very moment he had agreed to be the first president to speak at a Nixon-sponsored event in Washington. One columnist says, "Nixon knew perfectly well that the 'pathetically inadequate' line would generate exactly the kind of press coverage it got: it would make him look good, make Bush look bad, and generally serve his larger purpose."

Before a meeting of Republican leaders, Bush uncomfortably told reporters that he and Nixon were in "total agreement"—an astounding statement, since the memo was a blast at his policy. The president went on to say that there were "certain fiscal financial constraints on what we can do." He said he did not take Nixon's memo as "personally critical, and I think he would reiterate that it wasn't."

On Wednesday, March 11, at noon, in the ballroom of the Four Seasons Hotel in Washington, a long row of television lights was switched on. Hundreds rose to their feet from their luncheon tables as the grinning former president strode in from a rear exit, shaking hands up the entire length of the room. An elevator operator said, "He's looking old."

Pat Nixon was absent. Only twice since 1974 has she joined her husband for a public ceremony. Once was the opening of the Nixon Library. At the other, the Reagan Library's opening in November 1991, she collapsed out of camera range. Someone called for President Bush's physician. Protectively Nixon swept his wife into their car, saying, "No doctors!"

Now the former president took his place at the table nearest the dais. Sitting next to him was the former U.S. chief justice Warren Burger. Appointed by Nixon, he had nonetheless written the Supreme Court opinion demanding the White House tapes and sealing Nixon's doom. At the next table was Richard Helms, whose C.I.A. Nixon had tried to use as a scapegoat during Watergate. Elsewhere in the room were even a few names from the Nixon White House "enemies list," such as Daniel Schorr, once of CBS. The Washington columnist Charles Krauthammer observed, "The statute of limitations on Watergate has run out."

After a luncheon of com bisque and grilled salmon, Nixon rose. With his left hand in his trouser pocket, using no notes or lectern, Nixon delivered his thirty-fiveminute plea for aid to Russia, omitting the scathing references to Bush. Henry Kissinger later told a friend that his old boss wrote out such addresses on a yellow pad, memorized them, and rehearsed them before a mirror.

That evening, George and Barbara Bush, wearing formal dress, were driven over from the White House. As Richard Helms observed, the president and Nixon "passed the loving cup." Of the guest of honor, Bush declared, "I value his advice today. I get it. I appreciate it." As Nixon nodded fiercely, the president denounced "isolationism" and "protectionism": "Turning our back on the world is no answer. I don't care how difficult are our economic problems at home."

One member of the audience, Julie Nixon Eisenhower, said, "We couldn't be sure this day would come. But I never stopped believing."

On April 1, Bush announced a large new aid package for the former Soviet Union. That same day, John Hockenberry reported on National Public Radio that Richard Nixon, "whose political star has been ascending," had just made an announcement in New York. Listeners heard the familiar voice saying that having taken "the longest and hardest road" from "oblivion" and "won back your confidence" he was asking his fellow Americans once again to "make me your president."

It was all an April Fools' joke, with Nixon's voice supplied by the impressionist Rich Little, but many of those who enthusiastically called in did not know that. T-shirts appeared in Washington novelty stores: HE'S TANNED, HE'S RESTED, HE'S READY: NIXON IN '92.

Ronald Reagan once said of John Kennedy that only in the twilight of battle was it possible to see the splendor of the colors on the other side of the field. In 1992, many Americans feel the same way about Nixon. Two decades after Watergate, they appear to value more than at any time since 1972 Nixon's intellect, depth, creativity, and tenaciousness.

According to a Vanity Fair poll by Yankelovich Clancy Shulman, Richard Nixon has come a long way. The poll, conducted by telephone among four hundred respondents between March 27 and 29, shows that, while 71 percent believe that Nixon's actions warranted his resignation, 66 percent feel his views should be "respected and taken seriously as the thinking of an elder statesman." Asked whether the former president should be excluded from any formal position in the U.S. government, 63 percent of the respondents say he shouldn't be.

The poll suggests the degree to which the Iran-contra affair may have affected Americans' view of Watergate. Asked which of the two scandals was worse, 42 percent say Iran-contra, 40 percent Watergate. The poll shows them just as divided (47 to 49) on whether the country should "forgive and forget" Nixon's actions.

Sixty-nine percent consider the former president a "tough negotiator," 64 percent an expert on politics and foreign affairs. Fifty-two percent say that Nixon has a "clear vision" of America's world role. Forty-eight percent consider the former president "underrated." Thirty-six percent believe that he did a good or excellent job as president.

Poignantly for Nixon, this victory may prove to have been Pyrrhic. From time to time in recent years, despite the vigorous efforts of Nixon's lawyers and the slowness of transcription and processing, the National Archives has released snippets of his White House papers and tapes that sweep back the curtain for a peep at the private, vengeful Nixon of old.

The transcripts of forty-seven hours of tapes released in June 1991, for example, show Nixon suggesting to H. R. Haldeman that the Teamsters Union could be used to break up anti-war demonstrations: "They, they've got guys who'll go in and knock their heads off." Haldeman replies, "Sure, murderers, guys that really—you know, that's what they really do." At another point, Nixon asks, "Aren't the Chicago Seven all Jews?" He refers to his own supporters as "the finance contributors and all those assholes."

Nixon began making these recordings in 1971, so that his presidential library could one day present an edited version that would show the thirty-seventh president making the great decisions of peace and war. Thanks to Congress and the courts, the remaining 3,900 hours of tape will instead someday be released in full.

Every president says things in the seclusion of the Oval Office that he is not proud of. This is probably more true of Nixon than most. His private talk will be revealed in a way that no other president has ever had to endure, or no doubt ever will. Historians will set the tapes in context, but the cumulative effect of this material will almost certainly be another massive assault on the public perception of the thirty-seventh president. No one must be more aware than Richard Milhous Nixon that his "final comeback" could well turn out to have been merely the moment before the deluge.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now