Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

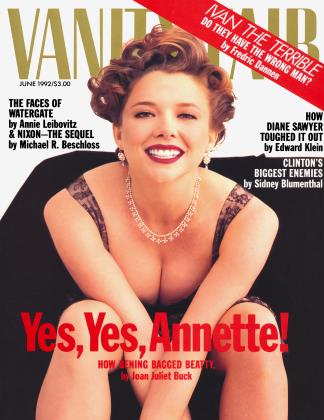

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE SECRET WAR FOR THE WHITE HOUSE

While Bill Clinton toughs out one of the bloodiest campaigns in recent history, the Republican machine is gearing up for the real battle

SIDNEY BLUMENTHAL

Politics

'The politics of personal destruction," as Bill Clinton calls them, have so far overwhelmed the 1992 edition of the making of the president. Clinton's inevitable nomination as the Democratic presidential candidate will hardly signal an armistice in the covert war raging over the "character" issue. Rather, it will launch a new, even more intense offensive. In the general election, the process of ripping and tearing will only get fiercer, the clandestine struggles of political agents and the media bloodier. "The Republicans," despairs a senior Clinton adviser, "will do all they can to keep the rumor machine running."

As Clinton tries to suture his wounds, George Bush is sharpening the long knives. Ominous anticipation of Bush's negative campaign against Clinton is now the central tension in the presidential race. The question of what Bush may have on Clinton in the way of "political pornography," as one prominent Republican puts it, has almost become a national obsession. "The Bush campaign is resolved that character assassination on Clinton will work as well as it did on Michael Dukakis," says an influential Republican consultant close to the re-election effort. "They have no uplifting or forward-looking plan to sell George Bush. Of course, they would deny that right now." Another Republican operative involved in the Bush campaign promises that by Election Day "there won't be anything left of Clinton."

The lurid rumor mills of old Hollywood were a quaint cottage industry compared with those of the postmodern campaign. Hit squads, spy networks, and counterintelligence units fight a daily underground battle, only the haziest outlines of which are reported on the evening news and the front pages. "It's a war fought on several fronts," says George Stephanopoulos, Clinton's deputy campaign manager. What he describes is the law of the jungle: a struggle to the death of one against all. "It's a war against rumors, a war against tabloids, a war against Republicans, a war against other Democrats, opponents and otherwise. They've figured out that as long as you can keep a rumor in play it doesn't matter if it's true, because the fact of the rumor creates a dynamic which makes people more willing to investigate and more willing to print stories that wouldn't otherwise be news. It's not enough to dispute the rumor—you have to disprove it. The burden of proof is shifted to us, even though the accusers have zero credibility. We're guilty by suspicion, guilty until proven innocent."

In 1992, the character of politics has reached a watershed. The secret war has become more important in creating the image of a candidate than substantive reportage, than debates on the issues, or even than television ads—all of which have been reduced to playing off the subterranean battle.

The Republican Party has been planning for the imminent clash for a long time. More than a decade ago, the secretive opposition-research team at the Republican National Committee began tracking Bill Clinton. The millisecond he appeared as a blip on its national radar screen as a thirty-two-year-old candidate for governor in obscure Arkansas, the process of accumulating potentially damaging material began. ("And if you have anything on Clinton when he ran for Congress [in 1974]," says an R.N.C. official, "I'd love to talk to you. ") Currently, about 350 Democratic politicians are the subjects of the far-flung Republican intelligence operation, which is unmatched by the haphazard Democrats. Any Democrat who runs for governor or Congress can be assured that he or she has a thick file at the R.N.C. that cannot be opened by invoking the Freedom of Information Act. And any Democrats whose contemplation of ever running for president is known outside their immediate family should operate on the assumption that every public utterance and every private act that operatives can trace will be used against them.

On the second floor of the brick warren of the R.N.C.'s offices, a few leafy blocks from the Capitol, the atmosphere in the opposition-research unit is something like that of the quiet, almost archival information-gathering to be found just across the Potomac, in Langley, Virginia, at C.I.A. headquarters. The department that the late R.N.C. chairman and negative-campaign expert Lee Atwater referred to as "the basement" is known to those who work there as Oppo. At the height of general-election campaigns, the staff balloons to more than forty diggers who glean information from more than 1,400 sources.

Each region of the country is surveilled by a division leader, a deputy, and a team of underlings. Almost every newspaper, from the smallest provincial weeklies to the metropolitan dailies, is clipped; the stories are catalogued, and every signifying word is coded into a special software program so that it can be recalled at the tap of a keyboard. Who knows what long-forgotten detail from someone's past, if detonated at the right moment, might destroy his career? (Clinton on "race," Clinton on "environment," Clinton on "Miss Arkansas.") Everywhere the subject has ever traveled and everyone he has met are accounted for. Everyone who has ever worked on the staff of or even contributed to the campaign of the subject is recorded and scrutinized. Any imbroglio involving these ancillary figures might eventually be deployed. "You pick your most potent thing," explains a Republican consultant who formerly helped direct the operations. And if there is nothing "potent" on the candidate, "there may be some things on the staff."

In the meantime, the political division maintains contact with local Republican leaders and others—including former police detectives and F.B.I. agents— who can exhume political skeletons. The information collected is not allowed to yellow and crumble, or get lost in a cabinet. "It would fill walls in hard copy," says the G.O.P. source. Rather, the files, known as "the Archive," are stored in a constantly humming computer—a mainframe is required for the voluminous task. "This never stops," says an R.N.C. operative. "It is never-ending."

It was this R.N.C. ministry and an Oppo group at the Reagan-Bush campaign that helped feed the stream of stories that almost drowned Geraldine Ferraro im£ mediately after she was nominated for vice president in 1984. And it was thanks to this network that the embattled Lee Atwater, George Bush's campaign manager in 1988, was able to excavate the Willie Horton and Pledge of Allegiance issues that buried Michael Dukakis.

In April, the anticipation of the coming anti-Clinton offensive prompted the president to issue a strict edict to his campaign staff "to stay out of the sleaze business." Anyone who disobeys, he said, will be summarily fired. Part of the reason, one Republican operative suggests, may be that Bush himself is wary of the issue that his son George junior referred to as "the big 'A' " in 1987, pre-emptively raising it in Newsweek after the Gary Hart affair in order to dismiss it. "But even if nothing else comes out about Clinton between now and the election, it doesn't matter," says a Republican consultant involved in Bush's campaign. "The point has been made. They don't need another specific action. They just need a message to surface in people's minds."

And the Republicans are well aware that much of the dirty business of surfacing that precise "message" during the campaign will be undertaken, without any direct link to the White House, by independent-expenditure committees and other free agents aligned with the G.O.P., such as the National Rifle Association. The dive-bombing Americans for Bush committee, which launched the Willie Horton television spots last political season, has reorganized itself as the Presidential Victory Committee for this year's election. "We will spend $10 million in this cycle in support of President Bush," pledges Floyd Brown, the committee's chairman. "I'm not going to say what we're going to do in our advertising, but I would just say that the whole race is going to turn on character. I don't think just Gennifer Flowers is the deathblow. To be honest, we haven't finished our research. I think the skeletons have just started to fall out of Clinton's closet."

"The Bush campaign is resolved that character assassination on Clinton will work as well as it did on Michael Dukakis"

I feel like I'm trapped inside a David Lynch movie," gasped one of Bill Clinton's senior aides about the Little Rock horror show in which he suddenly found himself hyperventilating. The Star's story about Gennifer Flowers had just been published. That week, in the middle of the night, the phone rang in the apartment of David Wilhelm, Clinton's campaign manager. The caller ticked off names of women, presumably women with whom Clinton had had affairs. "You're through, Wilhelm, you're through. ' ' Click. At three in the morning, one of Clinton's press aides was awakened by another anonymous caller: "Your heart is going to be tom out. You're going to be dead." Click.

Downtown, Dr. Taibi Kahler opened his office to discover that it had been broken into during the night. The files under the letter C had been rifled. Kahler, a speech analyst who has worked with NASA astronauts, is a Clinton friend who for years has advised him on his public speaking. Kahler, however, keeps his Clinton file stashed elsewhere. "There wasn't anything embarrassing to Bill anyway," he says. The burglars left behind a cryptic note that alluded to "Nashville," where Clinton consults with an allergist. "The note," says Kahler, "was a clear reference to Bill."

Tabloid reporters decamped to Little Rock, calling every woman even remotely bruited to have had an affair with the governor, offering large sums of money if they would talk. It was well known that Flowers had received more than $100,000 from the Star. "Copycat bimbos," as the campaign staff called them, rang the Clinton headquarters and the governor's mansion, threatening to "tell all" if Bill would not come to the phone. One of the women propositioned by a tabloid with a Flowers-size fee, uncertain about what she should do, contacted Linda Bloodworth-Thomason, the Arkansan producer of Designing Women and Evening Shade. "I have a profile as someone extremely concerned with women's issues," explains BloodworthThomason. "I was very distressed that the women of Arkansas were being used as pawns in this unsavory political game. The woman told me she never had an affair with Bill Clinton, never had a one-night stand with Bill Clinton, nothing with Bill Clinton. She also knew of two other women being contacted who never had affairs with Bill Clinton but were thinking about taking the money. I think she was tempted because of the amount of money involved. She said they told her, 'Just say anything.' " In the end, the woman rejected the offer.

Even before the Flowers story, however, the Clinton campaign had been strafed by rumor. Penthouse published a story by a rock groupie, Connie Hamzy, a.k.a. "Sweet Connie," who claimed to have been seduced by Clinton (in addition to her sexual volunteer work with innumerable rockers). By the time the campaign had located three eyewitnesses who were with Clinton when Sweet Connie claimed she had met him, and who refuted her story, CNN had already broadcast her account. (The network never bothered to correct its report.)

Two months later, amid the frenzied New Hampshire primary, Clinton's senior advisers were consumed by another scandal. The Nashua Telegraph told the campaign, according to Stephanopoulos, "We've received a tip on a story very, very damaging to Governor Clinton. We can't tell you what it is, can't tell you who's saying it, but we're going with it tonight. We want you available for a response." The Clinton aides spent six precious hours, just days before the vote, waiting at the newspaper's offices. Finally, at eight that evening, the scoop was revealed: it turned out that a disgruntled temporary driver for the Clinton staff had misunderstood a conversation about a campaign worker's salary in Washington, imagining the discussion was really about hush money for Gennifer Flowers.

Clinton, caught in this wind tunnel, was lacerated by the twisted shards of his personal history before he could establish any protective political depth. Once the early line settled in, it proved impossible to erase. His attempts to rebut the stories never caught up with the initial impression. And his occasionally facile explanations, sometimes fudging details, only reinforced the notion that he is fundamentally evasive and dishonest. The pejorative tag of "Slick Willie" was sticking partly because he was so unslick in his own defense.

Of course, it is a legitimate function of the press to investigate politicians. And some of the critical stories about Clinton—his cozy relations with certain Arkansas business interests, his environmental impact, his sometimes evasive rationalizations—have been essential in making an overall assessment of him. They are not simply "rehashed" stories already done by the Arkansas press, as Clinton has charged, but more comprehensive and focused; reporters from the outside, moreover, bring a fresh perspective. But as the drip of journalistic acid on Clinton's reputation continued, almost every major story about him and his background was entirely recast in the scandalous mode as an illustration of his flawed character.

A true chronicle of the 1992 campaign, then, must include an anatomical description of the circulatory system of rumormongering. Near the heart of the system are the political consultants. The rumors during the early primary season, from Flowers to the draft, were mostly "driven by a lot of people in the Democratic Party and the media," observes a prominent Republican. "The ones pushing it are the same losers involved in the same crashand-bum operations for the last fifteen years and aren't part of the Clinton campaign. If they can't be in the photograph, they want to destroy the candidate."

One pollster for Senator Bob Kerrey who was anonymously faxing scurrilous material about Clinton to CBS was dismissed by the startled candidate when the aide's act was exposed. Kerrey even labeled him a "hit man." But he was hardly alone. Another of those spreading early, wild rumors was a Democratic consultant angry at Clinton because he was not hired for the campaign.

The consultants who want to spin a story out of control need reporters to do their work. The relationship is mutually dependent. For the national press in Washington, the truly personal relationships are no longer with the politicians; that would cross the line of objectivity. Rather, the binding ties are to the corps of consultants—the permanent sources.

A Clinton press aide was awakened by an anonymous caller: "Your heart is going to be torn out. You're going to be dead." Click.

Furthermore, reporters do not actually have to print or broadcast what they hear to have an impact. Journalists who are professionally proud to bear the trophies of inside dopesterism have only to hoist them in hotel bars. Here is a partial list of the unsupported rumors that have been brandished in recent months: Bill Clinton propositioned the young daughter of Ron Brown, the chairman of the Democratic National Committee. Bill Clinton has an illegitimate child, and a black anchorwoman in New England is the mother. Bill Clinton has regularly snorted cocaine in the governor's office, and the Los Angeles Times is publishing the story on Thursday. (This rumor prompted Betsey Wright, Clinton's former chief of staff, who was being interviewed by the L.A. Times on another story, to volunteer a denial about cocaine, which the newspaper published—a story about a nonstory catalyzed by a rumor.) Bill Clinton had an affair with Elizabeth Ward, the 1982 Miss America from Arkansas, and Playboy is doing a big spread. (In the magazine, she replied, "I don't believe that's anyone's business," when asked if she'd had an affair with Clinton. Then she held a press conference to deny that she ever had.) Bill Clinton once beat up a political opponent. Bill Clinton once beat up his former law partner and close friend, Bruce Lindsey. Bill Clinton beat up his former pollster. Bill Clinton fondled a young woman he cornered in an elevator. Hillary Clinton has had a number of affairs. Hillary is gay. And so on.

"This is a very small, incestuous community," says David Lauter, who is covering the campaign for the Los Angeles Times. "Sometimes rumors get spread because reporters want to sound knowledgeable and up on the latest inside thing. People have convinced themselves that there must be something out there. Having done that, they've convinced themselves that there must be stories about it. Anytime they hear that a newspaper has an extra reporter in Little Rock they start attaching these ghost stories to that reporter."

Before the Colorado debate, a group of journalists gathered to "trade rumors back and forth about stories that we were supposedly about to do," recalls one political reporter. For a half-hour the discussion centered on an electrifying Los Angeles Times story involving Clinton and drugs that "would end his campaign the next day." Suddenly, a reporter from the L.A. Times, Ron Brownstein, appeared and was pounced upon. The reporters excitedly demanded the details of the expose. There were none. "It was constant for at least ten days, someone pulling me aside, asking me when it was coming out," says Brownstein.

"It's this year's parlor game in Washington: What do you know about Bill Clinton that will do him in?" says a well-connected Republican who has played key roles in the last two presidential campaigns. Another veteran Republican strategist attended the mid-March banquet in Washington for the Nixon Library and found himself engulfed. "There was a very important editor regaling my entire table with the story that his paper had uncovered that Bill Clinton had an illegitimate black child. It was cocktail chatter. It's unprovable. Another woman, the wife of a news executive, said she heard that Playboy would run a spread next month of eight women—'The Women of Bill Clinton.' It's hard to sort them all out, the things I've heard."

"Don't worry," a big moneyman for Kerrey confidently assured his colleagues in late February. "Clinton will be knocked out of the race in a week by a drug story, and then Kerrey will win." One reporter, jaded by the ceaseless whispers, reflects, "If we had a buck for every time we've heard Clinton's dead, we could quit this gig." But these stories are the new currency of insider trading. In the political world, unlike the financial, the profit comes not from how closely one can hold the inside dope but how widely one can spread it. By the time the campaign reached New York for its early-April primary, the hip, knowing types were retailing rumors that had been traded months ago in Washington: "You mean Clinton doesn't have an illegitimate black baby?" went one conversation among local journalists at the downtown Cafe Loup. "Why, I heard it yesterday from Jim"—a well-pluggedin writer whose reputation for knowing lent the story credence.

The charged atmosphere has even set off uncontrollable chain reactions: Gennifer Flowers' story eventually begets Hillary Clinton's speculation in Vanity Fair about Bush's alleged mistress; the media's chasing after Bill Clinton begets ABC News's tale of Jerry Brown's supposed tolerance of drug use, featuring anonymous, shadowed sources. Politics has become a perpetual-motion machine of scandal.

How did all of this start? The genealogy of the Clinton "scandals" can be traced through his political rise in Arkansas and his rivalry with a figure who has emerged as his most embittered, indefatigable foe. Over the last two decades, Clinton became the central character in a tangled southern-gothic political play. He believed that in taking his long step into presidential politics he was leaving behind the parochial battles of his past, but he soon found that the cords were coiled tighter around him than ever.

In the political mythology of Arkansas, Clinton is the golden boy, who at the age of sixteen shook hands with President Kennedy, and became infatuated with the romance of politics. On to Georgetown University, a Rhodes scholarship, and then to Yale Law School. He returned to Arkansas, determined to become governor and to raise one of the most backward states to modern levels. "Thank God for Mississippi" was the unofficial state slogan, expressing gratitude that there was at least one place that ranked lower. But in his very first campaign, his race for a House seat in 1974, he lost by four percentage points—in part because of a rumor that he was the man in a photograph of a bearded antiwar protester perched in a tree outside the University of Arkansas student union the same Saturday President Nixon was on the campus, attending an ArkansasTexas game. (Clinton happened to be studying at Oxford at the time.)

"We've received a tip on a story very, very damaging to Governor Clinton. We can't tell you what it is...but we're going with it tonight."

Elected governor in 1978, he moved too swiftly with sweeping reforms and was narrowly defeated in 1980 by a man whose greatest cause turned out to be creationism. Clinton came back in 1982 as a chastened, far more canny pol, cutting clever deals with the legislature.

Some to his left complained that he overcompromised, but many of their criticisms were a reflection of the expectations he had built. Slowly, Clinton was dragging "the land of opportunity" (the real state slogan) out of its retrograde condition, incrementally improving almost every social index. But his convoluted efforts at perestroika turned the state's politics into a complex, dangerous game, with himself as its total focus. "Clinton is an enigma," says Mike Gauldin, his press secretary. "We want somebody who carries the banner for us, who shows the world Arkansas is O.K., but we resent the guy who can do that. There isn't any politician in Arkansas history who is so intensely loved and hated. ' ' There is one man in Little Rock who hates him most of all, the governor's sworn enemy, who has somehow remained a virtual secret outside Arkansas. He is Sheffield Nelson, a wealthy former gas executive, once an ardent Clinton supporter, and now the co-chairman of the state Republican Party and the chief bone-rattler of Bill Clinton's skeletons. In his obsessive pursuit of Clinton, Nelson resembles police inspector Javert in Les Miserables, whose sole purpose in life is to hunt down his prey. One prominent Arkansas journalist refers to Nelson simply as "Hannibal Lecter." "If I were doing a movie," remarks Linda Bloodworth-Thomason, "the quintessential bad guy is Sheffield Nelson. He's got everything but the twirling mustache and the lady tied to the railroad tracks."

The story of Clinton's antagonist is a classic tale of American success. Sheffield Nelson was a poor boy, son of an itinerant laborer, who, when he was the student-body president at the University of Central Arkansas, had the rare good fortune to impress Witt Stephens, confidant of governors and the patriarch of the most powerful family in the state. (Stephens, Inc., of Little Rock is one of the largest bond-trading houses off Wall Street, and the Stephens empire encompasses energy resources, real estate, and banking.) Mr. Witt, as he was deferentially called, adopted the youthful Nelson as a surrogate son and raised him up until he was made the head of the Stephens-controlled Arkla, Inc., the largest natural-gas company in the state.

In 1973, Stephens retired from Arkla, though he maintained control through a loyal board of directors. When Nelson proposed several modernizing programs, however, the board fought back—apparently at the behest of Nelson's mentor. An intense three-year power struggle ensued. Nelson finally persuaded the board to back his more efficient policies, which ceased catering to other Stephens-owned businesses—alienating Mr. Witt and his family forever. Years later, at about the same time that Clinton was elected governor for the second time, Nelson cut a lucrative deal with one of his best friends, Jerral "Jerry" Jones, the head of the Arkoma Production Company (and now the owner of the Dallas Cowboys). The arrangement ended up locking Arkla into paying a higher-than-market rate to buy gas from Arkoma in exchange for a $45 million investment by Jones. Not incidentally, the deal slighted Stephens Production Company, the family-controlled firm, which held a less advantageous contract.

In the mid-eighties, Nelson harbored ambitions to run for governor. He was a Democrat who had backed liberal presidential candidates: Ted Kennedy in 1980 and Walter Mondale in 1984. In anticipation of his own gubernatorial bid, Nelson held fund-raisers for the state party and ingratiated himself with Bill Clinton. The governor appointed him head of the Arkansas Industrial Development Commission, which Nelson used as a vehicle to travel around the state to make political contacts. Nelson sought favors large and small from Clinton, even asking that the governor nominate him for the Horatio Alger Award (which he did). But Clinton ran again in 1986 and, after some hesitation, announced for 1990. Nelson was profoundly frustrated.

Yet certain events within the Republican Party, in Washington and Little Rock, were about to propel him into the arena. At the core of the G.O.P.'s grand design to become the prevailing force into the twenty-first century lies a Southern Strategy. Under George Bush, elected president with a solid South, the ultimate political architect was his party chairman, blues guitarist and negativecampaign maestro Lee Atwater from South Carolina. One of the biggest obstacles to his blueprint was the most intractably Democratic state in the South, Arkansas, and its leading Democrat, Bill Clinton.

"We really felt we had a shot at Bill Clinton, but we didn't have a candidate," says one of Atwater's former deputies. In his R.N.C. office, Atwater greeted a Democratic congressman from Arkansas, Tommy Robinson, and made an alluring proposition: change parties, run for governor, and get full G.O.P. support. In 1978, when Robinson was still a small-town police chief, Clinton had appointed him director of the State Public Safety Department. Robinson was then elected Pulaski County (Little Rock) sheriff, and became what many describe as something out of Smokey and the Bandit—but more Jackie Gleason than Burt Reynolds. He arrested a county judge and a comptroller to protest what he thought was inadequate financing of his office; he got himself jailed for contempt of court; he handcuffed fourteen countyjail prisoners to a guard tower. In 1984, he was elected to the House.

Robinson had already conducted a private poll that showed he couldn't beat Clinton for governor in a Democratic primary. But if he ran as a Republican, Atwater "promised the whole boat," says the source. "Robinson would be his top priority. He would have complete R.N.C. and White House support. " Moreover, Jackson Stephens, Mr. Witt's younger brother, had become a big backer of Bush, and would help Robinson. "I'll switch," replied Robinson, who was soon at the White House with the president of the United States blessing him for becoming a Republican. But that announcement triggered another one shortly thereafter: Sheffield Nelson, infuriated that the Stephens-backed Robinson might pre-empt him from attaining the capstone of his career, had also decided to switch parties and run for governor.

All sorts of pressures were applied against Robinson. According to a source close to Robinson, his boyhood friend Jerry Jones (yes, that Jerry Jones) told him to get out of the race or pay his personal debts to Jones, which came to about $1 million. (Jones did not respond to calls for this article.) To cover his financial strains, Robinson kited checks at the House bank, becoming the single largest transgressor there—996 overdrafts totaling $251,609. But what most plagued the Robinson campaign at the time was a series of "strange" occurrences, according to a source close to Robinson, that were eerily similar to those that would later haunt the Clinton campaign in the aftermath of the Flowers story. J. J. Vigenault, the former chairman of the Bush campaign in Arkansas, who had been assigned by Atwater to work for Robinson as part of the deal, was trailed everywhere he went by the same mysterious car. The campaign traced it to a private-detective agency. Other Robinson advisers were also followed. In the parking lot across from their headquarters, campaign workers spotted a man with a zoom lens snapping photographs. Some top Robinson aides received anonymous threatening phone calls in the middle of the night. "It was just so strange," says a source who received one. Robinson's handlers suspected that Nelson was behind it all. "I feel the guy would have done anything to beat us. If that was done to us," one says, "I don't doubt anything."

Nelson won the primary and turned his wrath on Clinton, who for the first time in his career was receiving substantial backing from the Stephens family. Against their arch-enemy, Nelson, "they had to support the man whose head they would have loved to deliver to Atwater," explains Skip Rutherford, the former chairman of the Arkansas Democratic Party. And Nelson had another reason to hate Clinton: at the governor's request, the state's Public Service Commission investigated the Arkla-Arkoma deal, ruling it "imprudent" and ordering Nelson's company to rebate more than $17 million to consumers who had been overcharged as a result.

"There was a very important editor regaling my entire table with the story that... Bill Clinton had an illegitimate black child."

Suddenly, the Clinton campaign found itself experiencing weird events: anonymous threatening phone calls in the middle of the night and campaign staffers feeling that they were being followed. Then, on October 19, 1990, in the heat of the race, a former college classmate of Nelson's, Larry Nichols, held a press conference. Nichols had been an employee of the Arkansas Development Finance Agency who had been fired two years earlier for making 142 long-distance telephone calls at state expense to leaders of the Nicaraguan contras. He now announced he was filing a lawsuit against Clinton, charging that he had been dismissed as part of a cover-up of a secret fund that the governor used to subsidize his dalliances.

Nichols listed five women who he claimed had had affairs with Clinton, and whose depositions he said would prove his case. One of those mentioned was Gennifer Rowers, who responded by threatening to sue a local radio station after it broadcast her name.

(Rumors of Clinton's extramarital affairs had long been rife, and they sometimes took on a phantasmagoric quality. A street minstrel, Robert "Say" McIntosh, who called himself "the sweetpotato-pie king," and who was well known around Little Rock for his eccentric public displays, passed out handprinted leaflets in front of the statehouse for years. "To my knowledge," reads one, "Gov. Clinton has had 40 black gals and 13 white gals. . .no wonder Arkansas is 49th and 50th in everything.")

After Nichols held his press conference, he sought advice from Robert Leslie, an Arkansas member of the R.N.C., about how to make the depositions of the women public. Yet Nichols never produced any depositions. During the primary he contacted Robinson's handlers, offering them his help. "I didn't want anything to do with him," says one of Robinson's senior advisers. "I thought he was a con man." Getting the brushoff from the Robinson campaign, Nichols "went to Sheffield," according to the Robinson aide. "I believe Sheffield funded the whole thing."

Nelson apparently was ready to turn the Nichols suit into a major issue to swing the campaign his way. He prepared a negative ad, with Nichols's story as its launching point, that accused Clinton of marital infidelity. The Arkansas newspapers refused, however, to publish a word about Nichols's lawsuit. Nelson, after much agonizing, scrapped his ad. Two days before the election, Nichols approached Clinton press secretary Mike Gauldin, offering to drop the suit if Clinton would give him $150,000 and a house. Clinton refused. On November 6, he won the election.

But Nelson was just beginning his pursuit. He got himself named co-chairman of the Arkansas G.O.P., and began retailing rumors he heard about Clinton. One reporter recalls telling Nelson a harmless fact about Clinton and then having Nelson retell it to him later, apparently forgetting its source, as the basis of a scandal he ought to investigate.

Over the last two decades, Bill Clinton became the central character in a tangled southern-gothic political play.

When Clinton was asked the adultery question in July 1991 by reporters and replied, "It's none of your business," Nelson hinted darkly to the Arkansas Gazette, "That works in Arkansas, but I guarantee you that, if you announce for president, it won't work."

When Clinton declared he was running for the Democratic nomination, Nelson feverishly tried to get reporters to write about the rumors of infidelity, for starters. Soon, according to a number of sources, Nelson's former press secretary, John Hudgens, helped put the Star in touch with Flowers, the failed chanteuse and hanger-on to local Republican pols, who had worked as a TV reporter for Hudgens when he was an assignment editor at KARK (Hudgens denies being the link). Finally, Flowers agreed to sell her story and heavily edited tapes of phone conversations with Clinton for at least $ 100,000.

Two days before Flowers held her press conference, broadcast on CNN, Nichols dropped his lawsuit—to little fanfare. Here is the essence of his barely noticed statement:

I want to tell everybody what I did to try to destroy Governor Clinton. .. . This has gone far enough. I never intended it to go this far.... It just kept getting bigger and bigger.... The media has made a circus out of this thing and now it's gone way too far. When that Star article first came out, several women called asking if I was willing to pay them to say they had an affair with Bill Clinton. This is crazy. One London newspaper is offering a half-million dollars for a story.... I have allowed the media to use me and my case to attack Clinton's personal life. There were rumors when I started this suit and I guess there will be rumors now that it is over. But it is over. I am dropping the suit. In trying to destroy Clinton, I was only hurting myself. If the American people understand why I did this, that I went for the jugular in my lawsuit, and that was wrong, then they'll see that there's not a whole lot of difference between me and what the reporters are doing today.

Thus began the "character" issue that has dominated the current campaign.

The next bombshell that shook Clinton, reinforcing doubts about his character, was the revelation of a 1969 letter he had written to Colonel Eugene Holmes, the R.O.T.C. officer at the University of Arkansas. The letter thanked Holmes for admitting the Rhodes scholar into the program, which exempted him from the draft. News stories depicted Clinton as a manipulative draft dodger. Overlooked was how the longburied letter had made its way into the public record from a number of mysterious sources. One leaker was James M. Tully, a partner in Global Research International, Inc., the shadowy company founded by former attorney general John N. Mitchell which sold helicopters and military supplies to Saddam Hussein and contracted with Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu. (Tully did not return phone calls for this article.)

The draft issue—which Clinton was unable to shake despite a 77/ne-magazine column by Strobe Talbott, his former Oxford housemate, corroborating his account—resurfaced during the New York primary with the leak of a new letter. This one, written by Oxford friend Cliff Jackson, noted that Clinton had once received an induction notice. It was a bureaucratic snafu Clinton had been advised to ignore at the time, but it seemed to undermine his honesty yet again because he had neglected to mention it. Jackson, however, is not a disinterested party. The Little Rock attorney, a former research director for the Arkansas G.O.P., has organized an independentexpenditure committee called the Alliance for the Rebirth of an Independent American Spirit (ARIAS), which bought dozens of anti-Clinton newspaper and radio ads in New Hampshire. Jackson's efforts have complemented those of Clinton's arch-enemy.

Sheffield Nelson's large comer office is located on the thirty-fourth floor of the TCB Y Building, the tallest in Little Rock, overlooking the twisting Arkansas River. His gray, businesslike mien is instantly dispelled by his rapid-fire twang. There is nothing muted or indirect about him.

"I know Clinton as well as anyone," he begins in a confidential tone. "His number-one drive is to be president. He's never been governor." The evil Stephens family, Nelson explains, feared his victory over Clinton in 1990. "The Stephenses knew I'd close down their playhouse." All their bond business with the state would have been cut off. "I'd have brought it all to a halt immediately. Their free ride would have stopped. " That's why they decided to purchase Clinton "lock, stock, and barrel."

It was, Nelson continues, only a gentlemanly sense of restraint that kept him from raising the question of Clinton's private life. "I could have beat his head off with women." But, Nelson says, he was not responsible in any way for the rumors about Clinton. Though he has been to Washington a number of times before, during and after the Flowers affair, he denies conferring with any Republican political operatives. He admits, however, that during his campaign against Clinton he sent a young lawyer to interview a prisoner in a state jail who had once worked in the governor's mansion and claimed to have sex stories to tell. "Once he got there," confides Nelson, "he heard some things gentlemen don't talk about. " Nelson says he didn't use the information because of the tainted source.

In response to the Robinson campaign's charges that Sheffield was behind the dirty tricks and strange incidents that plagued that campaign, Nelson snapped, "They're paranoid. Totally false. We didn't do very much. Tommy's good enough to shoot his own feet. He's got a motor-mouth that doesn't engage his brain."

As for Clinton, Nelson says contentedly, "He's being well toasted." And Nelson predicts that "there will be more personal issues coming out." His smile broadens. "Every day you'll see more and more. ... I'm just saying what I hear. ' '

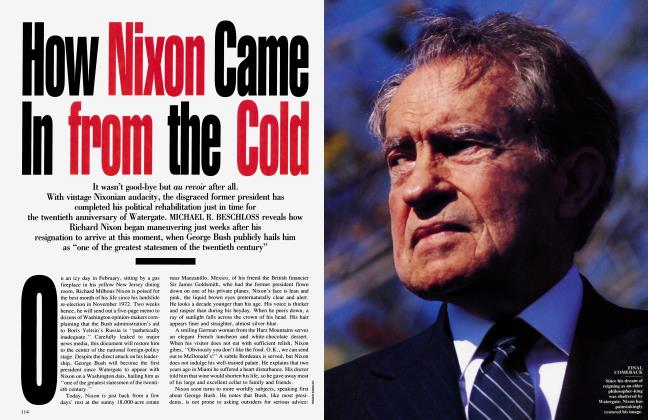

[If Clinton can get rid of the 'character' I issue," speculated a Republican stratlegist in April, "he's president of the United States, no question. But how does he get rid of it?" Then the Republican handler, who is close to Bush's reelection campaign, confided in exactly the same sotto voce tone in which he passes on rumors about Clinton, "You know, there's dirt in Bush's past, sleazy business deals."

Clinton understands that the "character" issue is not bogus, but he wonders whether his whole character will ever be presented. He sounds almost fatalistic as he leans back into the seat of his campaign charter airplane. "When you run for president, sooner or later, you have to confront all this. ... You know, we live in an age in which you're supposed to pretend that you hate public life, that this is an awful burden you've decided to do. But I was raised in a time when it was an honorable thing to do and when it was seen as the best avenue for change."

Some of his problems, Clinton says, are "rooted in the fact that I'm a complicated person." But, he adds, "a lot of it's being stirred because of the Arkansas enemies I have and the Republicans, because they know that's what sells, in spite of all the people who say, 'Well, we don't want another negative personal campaign.' "

Clinton shakes his head when he's asked about Sheffield Nelson. "I think when he was defeated he was a rich guy with a lot of time left in his life, a lot of energy, and he had one of two choices: one was to try to find something constructive to do and the other was to take all his venom out trying to bring me down. He's just so bitter. ... It was all stripped away, everything he'd ever stood for for years; he'd abandoned that not only by changing parties but all of the philosophical changes. It was all gone, there was nothing left. And now he just wants somebody else to hurt, too."

Bitter political jealousy and scandal, of course, are nothing new to American politics. The seamy thread has run through presidential campaigns from the beginning of the Republic. Consider: Which president sent love letters to his neighbor's wife—and was rumored to be a woman in drag? (George Washington.) Which candidate was married to a bigamist? (Andrew Jackson.) Which supported an illegitimate child? (Grover Cleveland.) Which authorized a gay sting operation while serving as assistant secretary of the navy and then tried to cover up? (Franklin D. Roosevelt.) Which had an affair with an editor of the main newspaper promoting his candidacy? (Wendell Willkie, the New York Herald Tribune.) Which divorced his mentally unstable wife and carried on a number of affairs? (Adlai Stevenson.) And this is only a smattering of the lowlights.

The chief bone-rattler of Bill Clinton's skeletons, the governor's sworn enemy, has somehow remained a virtual secret outside Arkansas.

But what has changed is the impact and legitimization of the rumor-mongering. Typically, the Willkie and Stevenson indiscretions were considered politically out of bounds by their opponents. The conditions under which this radical transformation has taken place are well known: disillusionment with politics; the collapse of the wall between the public and the private; the bastardization of investigative reporting; and the expansive web of post-industrial communications. The elements have now coalesced into a technopolitical structure that is easily manipulated by practiced operators.

All of this is bearing down on the 1992 campaign with accelerating ferocity. The enormous stakes in the presidential race—the future balance of power between the Republican and Democratic parties, the shape of the economy, and the country's role in the "new world order"—will be largely contingent upon whether the now institutionalized system of campaign by "scandal" will prevail as the dominant factor of American political life. Though the editors of the respectable media may deplore the trend, they not only seem incapable of reversing it but have been swept up by it themselves. There are no countervailing forces in sight—only increasingly naked motivations and exigencies. ' 'Clinton needs to be more than defeated in 1992, " says one Bush campaign adviser. "He must be destroyed, so we can beat him in 1996."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now