Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHOLLY SHIT!

A saleroom fable for the wigged-out generation

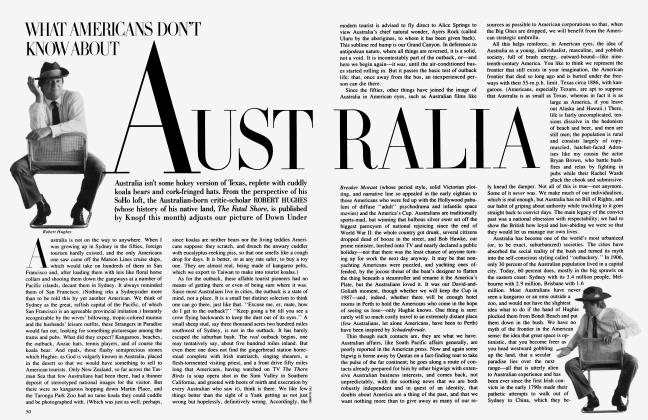

ROBERT HUGHES

Art

Though the details of the sale have blurred in the art world's memory, few of the devoted fans who were present at the ten-day dispersion of the earthly effects of America's first beatified art figure, the Blessed Andrew Warble, famed among his numerous worshipers as "The Little Flower of the Reagan Era," will forget its dramatic climax: a saleroom miracle, as a dead woman was revived by the touch of his wig before a praying and weeping throng at Christaby's in New York.

The worldwide auction house is known by its advertising slogan, "The only church where the icons are for sale."

The woman, corporate art adviser Barbara Glitz, president of Glitzkunst Associates, had been bidding for one of the 527 souvenir ashtrays accumulated over a lifetime by the Blessed Andrew, who did not smoke and never admitted visitors to his Biedermeier-stuffed hermit's cave in uptown Manhattan. In the heat of competition a rival dealer, representing the billionaire Japanese wilderness outfitter Ichiban Engawa, thirtyfour, stabbed her with one of the 213 silver Puiforcat toasting forks in the Blessed Andrew's collection.

Entrepreneur Engawa, best known for selling millions of white-water rafts to young Japanese who have never seen a river but regard them as necessary adjuncts to their Ralph Lauren aftershave—"postmodern rafting," as he christened it—denies having given his agent instructions to kill the rival bidder. A spokesman for Seppuku Adventureware put it down to "corporate zeal."

"Engawa has the greatest private collection of Zen teabowls in the world," the spokesman explained. "He wanted something in earthenware associated with the life of Andrew. In fact, he wanted everything in earthenware associated with his life. Very sorry."

The assailant, who immediately tried to kill himself with one of the Blessed Andrew's thirtyseven unmatched Adirondack porch chairs, was rushed to New York Hospital. "Actually," smirked an executive of the Warble Mint and Heritage Foundation, "the very place where Andy died. I don't know if he knows that yet."

"I just felt this terrible pain in the ass," said dealer Glitz, her normally rasping voice muted by awe, "the kind you sometimes get in the art world, so I paid it no attention. But then all of a sudden I knew no more, which isn't normal for me, I guess. All I could see was a great tunnel with a light at the end of it, and Andy standing there, smiling and eating a Pop-Tart."

Seeing her prone on the floor, the chairman of Christaby's, former construction mogul "Big Sal" Adorabile, tried unsuccessfully to apply mouth-tomouth resuscitation. Then a member of Christaby's board, Lord Flowery, broke a vitrine, seized one of Saint Andrew's wigs, and thrust several tufts of its fiber up Ms. Glitz's nostrils. "She sneezed," said the earl, formerly Margaret Thatcher's minister of cultural self-help. "And then she began to breathe, and sat up. It was a miracle. A sign of grace. God is my co-auctioneer. ' '

Lord Flowery denied any advance knowledge of the wig's powers. "We had ninety-one on consignment, all in the same case," he explained. "I just grabbed the first one, silver with pink frosting. Now that we've researched it we think this may have been the very wig the Blessed Andy wore on his very first visit to Iran, as a guest of the late shah, to do the four-panel portrait of the chief of savak—the one the Buckleys have in Gstaad."

The Wig was immediately withdrawn from sale by Christaby's. "You think we lost on the deal?" chairman Adorabile demanded at a press conference at the end of the day's bidding. "The clients went nuts for the other ninety wigs. We had some dumb bast. . .—I mean, a major connoisseur in Los Angeles with a historic collection, just historic—blockbuy six of them at 1.5 mil each. That's seventy-five bucks a hair, fellas. The Relics Department says the only thing that'd pull more is Vincent's ear or maybe Pablo's pecker, which would run eight to ten mil, and we're working on that, capisce?"

The apparent miracle caused frenzy among bidders for the day's remaining lots. Amid scenes of wild enthusiasm a Houston collector who had paid an average of $20,000 each for a group of some two hundred black-mammy cookie jars found in Warble's basement announced that they would form the nucleus of the Warble Chapel, a nondenominational meditation center—"nothing fancy, probably just a replica of Grant's Tomb by Philip Johnson"—to be built on the campus of Rice University.

Continued on page 41

Continued from page 32

Art

"The Relics Department says the only thing that'd pull more is Vincent's ear or maybe Pablo's pecker, which would run eight to ten mil, and we're working on that, capisce?'*

As soon as the sale was over, the director of the Warble Mint and Heritage Foundation, slender, brilliantined Fred Ewe, placed the parrucca santa, or "Holy Wig," in the hands of the church official promulgating the Blessed Warble's case for full canonization, Monsignor Ridiculi Ridicula of Vatican City. Devil's advocates in Castel Gandolfo have begun testing it for miraculous elasticity, but, cautioned Ewe, no firm findings can be expected yet: * 'This is the first time they have had to deal with a holy relic entirely made of plastic." "There is a fine line," explained Mgr. Ridicula, "between nonbiodegradability and incorruptibility, and one could never be sure which side of it the Blessed Andrew was on." The Warble Mint and Heritage Foundation has sent a "generous" contribution to the conclave through the Banco Commerciale dello Spirito Santo in Rome, he added.

The movement to canonize the painter, Ewe pointed out, had been gathering momentum since the British art historian John Giltframe read a paper at his funeral in 1987, entitled "From Soup to Nuts: Redemptive Iconography in Warble." In it he showed that Warble, far from being the greedy, affectless social climber his critics took him for, was in fact the last of the przyznychkili, or "Holy Nitwits," a penitential Slavic sect whose members once roamed the banks of the Don, chattering inanely and dispensing broth to the rich from goatskins.

Art experts expressed surprise at the high prices attained by the 1,745,435 lots listed in the sale's thirty-five-volume catalogue. The range was immense, but the quality uneven. "Andy was a true democrat," said one of the several dozen public-relations officers hired by Christaby's and the Warble Mint and Heritage Foundation to place identical pre-auction stories in Newsweek, New York, The Village Voice, Vogue, The New York Times, and The Washington Post. "That is, he touched everything, and kept whatever he touched." The objects in the six-month, ten-country, twenty-two-city preview ran from an unopened carton of Styrofoam cups to a sharkskin portable altar by EmileJacques Ruhlmann, a group of seventynine souvenir rosaries from Lourdes, and the gigantic canvas that hung above the narrow iron cot that served as a convertible prie-dieu and bed: The Ancient of Days Pours Forth the Vials of His Wrath upon the Sodomites, by the apoc-

alyptic English painter John Martin.

"The reason Andrew was such a saint," muses former museum curator Henry Goldbug, a longtime associate of the late Warble's, "is that he believed in the redemption of trash. He was the Mother Teresa of the gumball machine. Nothing was too ordinary for him, and he could never get enough of it. He would go down among the rejected of the earth and buy like there was no tomorrow, which, come to think of it, there wasn't."

The same view was echoed more profoundly by art historian Gudrun Paradigm, author of the forthcoming critical catalogue of Warble's works. "The aesthetic content of the collection is, of course, tangential to any post-structuralist debate regarding its function," she explained. "In collecting 1,400 cast-iron jockeys, he presented a (Actively) limitless accumulation of signs, a gesture-assite which designates the alienating hegemony of reification in the late capitalist economy, a critical act of exquisite significance."

But as usual the chairman had the last word. "I can tell you exactly what this auction means," he told a reporter over his shoulder on his way to the limousine. "It means Christaby's gets to call itself a religious institution, and we don't pay a goddamn cent of tax from now on."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now