Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLIBER EYE MAN'S

ROBERT HUGHES

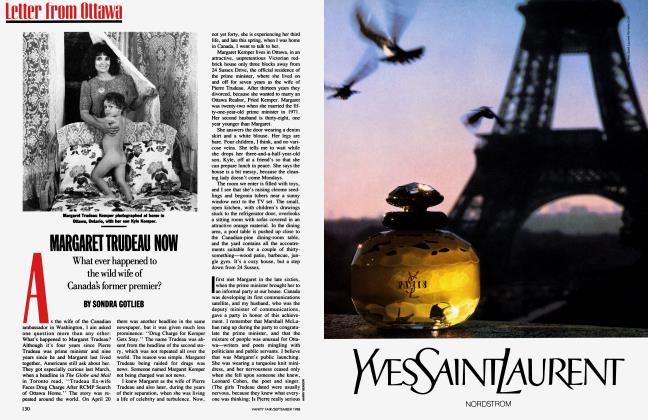

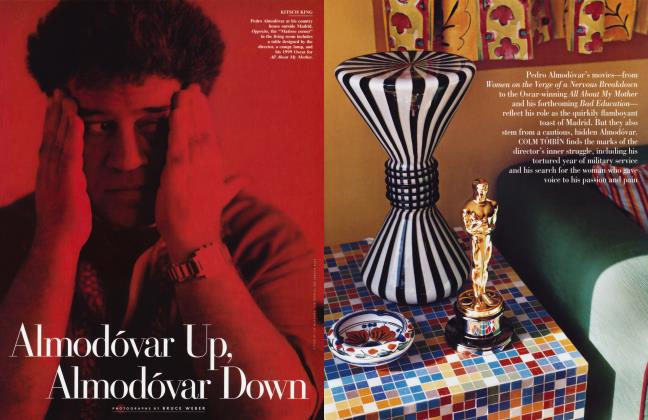

Forty years ago, the painter and sculptor Alexander Liberman began photographing and keeping notes on the masters of modem art, searching out clues to their creativity in their studios, their own "caves of making." The result was a new kind of art book. Now ROBERT HUGHES introduces for Vanity Fair the expanded edition of The Artist in His Studio, due this fall from Random House. And on page 214, we offer an exclusive preview

ALEXANDER LIBERMAN, JULY 1988.

In 1947 Alexander Liberman, the expatriate Russian who was not yet the éminence grise of Cond6 Nast and thought of himself mainly as a painter and designer, decided on a project. It had struck him that no photographer (except for Brassai and Cartier-Bresson, working on Picasso and Matisse) had ever tried to document in depth the members of the Ecole de Paris in their natural habitats, their homes and studios. What role, he wondered, did "the mystery of environment" play in their work? What relationship ' 'exists between the painting and the vision of reality that daily the artist has before his eyes?"

Liberman was too canny to suppose that environment determined art in a simple, one-to-one way. But he was sure it had some effect, deeper and more direct than the airy philosophizing of critics was apt to allow. And the most intimate part of the artist's surroundings was his studio—the cave of making, always changed by the secretion of images and objects, forever mirroring the artist's preoccupations back on himself and his future work. So he would photograph and if possible interview the great artists of the School of Paris, beginning with Picasso, Braque, and Matisse, in their studios. Even if the artist was dead—as Cezanne, Monet, Bonnard, Renoir, and Kandinsky were—it might still be worthwhile to make a record of his studio, before it was sold or altered beyond recognition. (In those days no one thought much about the studio as shrine; France had no equivalents to the Pollock-Krasner house in East Hampton, with its spattered floor. Kenneth Clark once showed me some strips of encrusted canvas he had swiped from Monet's studio in the early fifties—offcuts from the Nympheas, which nobody in the least minded him taking.) So Liberman took his notebook and camera and went to work as the Boswell of French art in the last days of its glory, the late forties and early fifties, a time when Paris was still the uncontested capital of Western art. The task used up nearly thirteen years of intermittent work. Its result was a unique record: The Artist in His Studio.

For in the late forties through the middle fifties, when Liberman got to them, most of the founding fathers of European modernism (and some of the mothers—Gontcharova, Sonia Delaunay) were alive and at work. Some, like Matisse, were at the peak of their life's achievement, but all were getting old. In 1947 Matisse turned seventyeight, Brancusi seventy-one, Derain sixty-seven, Picasso and L6ger sixty-six, Braque sixty-five. Nearly all the Surrealist generation was intact: Max Ernst was a stringy, white-haired fifty-six, Joan Mird fifty-four, Andrd Masson fifty-one, Dali forty-three, and Giacometti—still considered a "new generation" artist, like Jean Dubuffet—was forty-six. Today every one of them is dead, except for Dali, who is hopelessly senile. Liberman got to know them all, some intimately, others casually, and all the while he had his 35-mm. Leica in hand, discreetly snapping away with available light—no paraphernalia, no strobes or umbrellas, no assistants to startle the quarry and rupture the conversation.

In 1959 the Museum of Modem Art exhibited a selection of Liberman's photographs and the next year Viking Press published The Artist in His Studio. It soon went out of print and—perhaps because America's newfound obsession with the New York School truncated the market for books celebrating the School of Paris—remained unobtainable for nearly thirty years. (A scaled-down edition was printed in 1968.) This fall it will be published again by Random House, both cut and greatly expanded. Some minor French artists (Manessier, Bazaine, Borfcs, Gromaire, Pevsner, Segonzac, Laurencin, Hartung, Richier) have been dropped, and sections on Sonia Delaunay and Balthus have been added. The account of Picasso, whom Liberman continued to visit until 1965 and got to know quite well, has been enlarged from twenty pages of text and pictures to forty. Liberman, who makes no claims for himself as a writer, says he was embarrassed to reread the book. (Although he need not have worried.) But the photographs in the original were only a fraction of his archive; unlike the parallel work of Brassai and Cartier-Bresson, most of them are in color, and the color quality of the transparencies has held over the years. This is not merely a journalistic matter, since (for instance) Liberman's color shots afford the only record we have of the working palettes of Braque, Matisse, and others. The Artist in His Studio is an extraordinary achievement; from its pages the men (and some of the women) whom we now think of as the protagonists of a lost era stare with undiminished vivacity and pathos. As fine reporting revisited tends to do, this book carries a heavy weight of nostalgia.

When he began this long job, it cannot have been clear to Alexander Liberman that he was inventing a new type of art book. But that is what he did. The Artist in His Studio turned out to be the first and still by far the best of a long line, now almost a publishing clich6, of documentary projects that take the reader inside the working space of well-known painters and sculptors. From this came a whole slew of later documentary efforts—Tony Snowdon recording the artists of London in the sixties, David Douglas Duncan shooting Picasso at La Californie. (Picasso had asked Liberman to move in with him for three months to photograph his life and work, but Liberman had other obligations, and Duncan later took on the task.)

Subtly, in ways almost unnoticed at first, The Artist in His Studio helped change the idea of the modem painter or sculptor as public figure. In the nineteenth century, the Great Man would pose (for Nadar, for instance) in the photographer's studio, wearing street or formal dress, away from his workplace. It was shocking for a public figure to be informally represented in any medium—hence the furor over Rodin's conception of Balzac, mountainously wrapped in his dressing gown. No daguerreotype exists of Delacroix sketching in his studio on the Rue de Fiirstenberg; all we have of Degas is posed formal portraits and some late, rather blurry, snapshots of the old man on the street, though there are pictures of Monet, patriarchal in bulk and beard, before the easel in the studio and outside in the garden at Givemey. But these images occur before the age of photojournalism, with its ravenous appetite for images, its tyrannical curiosity. And before the moment of the Artist as Celebrity, too—the condition that dictates the terms on which privacy is surrendered. Today, like a bear in other people's Wilderness Experience, the artist is expected to provide the photo opportunity, shamble past the car, make the visit worthwhile. No such etiquette had established itself among artists in 1947, and The Artist in His Studio—discreet and even reverential though Liberman's approach was—was instrumental in creating the idea that an artist's working life as well as his work ''ought" to be available to the public: that artists had an aura which could be consumed.

But such matters were very far from Liberman's mind when he started out. He wanted to preserve, to record, and above all to make his act of homage to a heroic cultural epoch whose traces, in the war years just past, had seemed in real risk of extinction under the iron foot of Nazism.

For all his cosmopolitan background, Liberman in his late thirties and early forties was still, at root, an extremely idealistic Russian, and he believed—rather too much, perhaps, for the tastes of the eighties—in the image of the senior artist as monk, seer, staiets, and prophet, the last Holy Man in a secular age. (Thus Braque's white hair "shone like an aureole'' in the studio, and Brancusi "created a strange aura of wisdom. ... He made me think of a Buddhist monk and Merlin the magician.... He was outside of time and history... .The mysteries of Egypt, of China, and the Bible were always present in his thoughts.'')

Liberman had no sense of himself as a "professional'' photographer, and to a modem picture editor he could well have seemed wrong for the job; yet he did have a sense of mission and plenty of aesthetic background, which counted for much more when it came to knocking on artists' doors. Bora in Kiev in 1912 (his father

supervised the timberlands of the czar's family and then of the government under Lenin, and his mother ran the first state theater for children), he had been taken to London in 1921, stoically endured four years of flogging and fagging at an English prep school, and then gone to secondary school in France. He studied architecture under Auguste Perret, pioneer of reinforced-concrete construction and teacher of Le Corbusier; there was a stint at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, a course of painting in André Lhote's studio, and an apprenticeship to Cassandre, the great Deco designer and poster artist of the thirties.

In 1932 Liberman joined Vu, Lucien Vogel's Paris newspicture magazine, from which Henry Luce is said to have got the idea for Life. By 1936, he was its editor in chief. But he had never given up thinking of himself as a painter, and it was as an aspirant artist that, with some trepidation, he approached les grands. Hence they tended to trust him as they might not have trusted a photojouurnalist. Lasting friendships resulted, with Braque, Giacometti, and Léger.

The artist's eye served his subjects well. Much of The Artist in His Studio consists of photographs of the artists' motifs—Cezanne's Mont Sainte-Victoire, the lily pond and tremulous willows at Givemey—and in them Liberman showed an uncanny ability, without forcing things, to put himself in the spirit of the artist's rendering of the scene. The modest action of the camera reminds us that the painters, too, were looking at something real, not inventing it. The camera is always discreet. It peers past the half-closed doors of Renoir's salon, not wanting to intrude. It records, casually, the canvases still stacked in the long-dead Monet's studio. It renders the sea-washed granite of the Normandy coast in a way that leaves no doubt at all about the intensity of Braque's relationship to his landscape. It enters Pierre Bonnard's bathroom, not because it wants to satisfy a gossipy curiosity about how the dead man washed, but because this modest room with its wire soap dish and tin water heater was the theater of some of the greatest images of the nude ever painted. And it records the faces—Picasso's mobile monkey mask with its attention visibly shutting off and on, the seamed intensity of Giacometti, Vlaminck's coarse country-squire bulk, Balthus as intellectual faun, and the massive, oaklike presence of André Derain—with unflagging curiosity.

If Liberman entered their studios as a photographer, he finished his book as a writer—and the writing, though too hierophantic in places, is far better than he apparently thinks. His tone is that of a twentiethcentury Vasari, hero-worshiping, but with astringent overtones of Saint-Simon. He wanted to preserve his major subjects in their own words, though his energy flagged with some of them: where Picasso, Braque, and Léger get pages, Max Ernst and Jean Dubuffet are hurried through in a paragraph or so. Rarely does the narrator get in the way of the subject. The pleasures of the text he produced for The Artist in His Studio match and sometimes even surpass those of the images. It eschews the vulgarity of "personality" art writing and is jargon-free. At its best it attains an aphoristic magic:

Continued on page 260

Continued from page 213

A Bonnard canvas is like a minute section of an impressionist painting enlarged X times. The physical magnification gives scale and grandeur, but also an emotional increase. His painting is a poster of the subtle; it shouts in a soft voice; it advertises privacy.

Liberman's ear was good. It caught Picasso's harshly epigrammatic way of speech as well as it did the more convoluted reflections of Braque and the impatient whisperings of Franz Kupka's extreme old age. His vignettes of some artists are piercing and have not been equaled. Liberman jotted down notes of whatever struck him in conversation and wrote them up afterward—this being long before the cassette recorder changed the lives of reporters. He did not touch up what he found, and sometimes it recalls Gogol. We see Georges Rouault at eighty receiving Liberman, half his age, in his flat near the Gare de Lyon nearly forty years ago. Rouault wears a homburg and tie in the dim, crucifix-laden salon. He has "an extraordinary lunar face" with wrinkles "like the lines on a sensitive young hand." He shuffles about, endlessly replaying the record of his memories, long stylized by repetition, of the men he has known—the dealer Vollard, Cezanne, Degas, Renoir, all dead. He is bitter at the late arrival of his success; he rails at the unnamed young, and laughs convulsively, showing yellow teeth and "the rough humor of a country priest." As he replays the resentments of his life, obliviously reciting to his Russian Jewish visitor his Catholic's loathing of Dreyfus, Liberman looks from Rouault's homburg to his feet:

Although carefully and so formally attired, he wore felt bedroom slippers... telltale evidence that he lived an old man's life and perhaps was more of an invalid than he appeared. He gave the impression of an animal in a cage. One felt that Rouault was suffocating.... The sad house, the sad, dull apartment, were out of scale. ... There were flashes of extraordinary grandeur in his speech and gesture that contradicted the pettiness of what he said.

Some visits were dreadful, as when Liberman traipses out to Chatou to see Maurice Utrillo in his cement villa, six years before his death in 1955. There, in the suburban garden with its bedded begonias and dwarf-green picket, fences, hovers a wraith of a man, a bumt-out alcoholic with a harpy of a wife, who (needless to say) paints too, under the name Lucie Vallore. She blathers unstoppably about her own work, about going to the wedding of Rita Hayworth and the Aga Khan. "I ordered my husband a blue suit so that he would look more like a master." Speechless, Utrillo gazes at a garden statue of the Muse of Painting:

He shuffled towards the statue, examined it with curiosity and surprise, shuffled away, bewildered. Madame Utrillo followed behind her husband and turned him in whatever direction she saw fit, saying, as to a child, "Answer the gentleman, turn and smile; the gentleman wants to take your picture." He responded with monosyllabic sounds. ...Madame walked around her husband, asking: "Darling, don't you think I'm talented? Don't you like my work? Tell the man," she prodded, "what you think of my work. Don't you think I have made progress?" Utrillo emerged from his dreamlike silence to answer, "Yes, yes, oh yes."

The sculptor Liberman became in the seventies and eighties was already embryonic in the observer of the forties and fifties. He saw in particularly formal ways, ways that reflect his own Constructivist background. Here is Matisse in his bedroom on Boulevard Montparnasse:

The sheets, his face, his pajamas, the covering on the bed, all seemed bathed in the same yellow-white grayish mist.

This impression of softness was pierced by the sharp accents of light hitting the rims of his metal spectacles, hitting the thistles of hair that were his beard. The white beard, neatly clipped in a circular shape, gave an extra dimension to his face. The bald head and the round lenses of his glasses continued the circular movement. Only the perpendicular and the horizontal of the nose and mouth relieved the curvilinear mask.

His was no ordinary beard. It had been trimmed and shaped with a profound knowledge of form. It was more than a beard; it was a form fashioned in relation to other forms.

Liberman evokes in almost palpable detail the cramped, dusty cave of Giacometti's studio, and the details of ordered mellowness in Georges Braque's homes in Normandy and Paris, with their "Flemish intimacy and richness of texture." But this is not just to recite scenes of decor and squalor. It tells us something useful about how Braque grounded himself in material objects at home, only to pass (when in his Paris studio, designed by Auguste Perret) into something more rarefied for his work. The daylight in Braque's studio "is softened as if silenced; and, in the hushed luminosity, the contrast between objects ceases as they lose their individuality and fuse into their environment. This... creates a unique universe. Air, space between things acquire tangible substance." The replete void of Cubism, in fact, though not brown.

Liberman's own sympathies are always clear. He is for mysticism and exaltation, but against the tyranny of self-display, the Expressionist ego. His essential text is Pascal's Le moi est haissable—"The ego is hateful. . . . The ego has two qualities: it is unfair in itself, in that it puts itself at the center of everything; it is incommode to others because it seeks to enslave them, for each ego is the enemy and wants to be the tyrant of all the rest." Liberman's sympathy flowed toward a self-made classicist like Andre Derain, whose later work was wholly out of fashion in the fifties: "His early paintings were highly prized; but he had wilfully turned away and struggled to re-create a classical tradition against all the egotism and expressionism that was flourishing among his fellow artists." But most of all there was Braque, of whose ideas The Artist in His Studio presents a unique record. Here he is on Pascal's moi:

I sometimes have the impression that it is not me who did my paintings. I feel absolutely detached at first glance. It is absolutely as though they were someone else's. But when I concentrate, then I see a lot of things. One's style—it is in a way one's inability to do otherwise.... Your physical constitution practically determines the shape of the brushmarks.... Personality is good if it reveals itself without the artist's becoming conscious of it. There must be no exploitation of personality.

Try reading that aloud next Saturday afternoon on the comer of Spring Street and West Broadway. In more ways than one, The Artist in His Studio is a tract for our times.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now