Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGoyas Fierce Light

ROBERT HUGHES

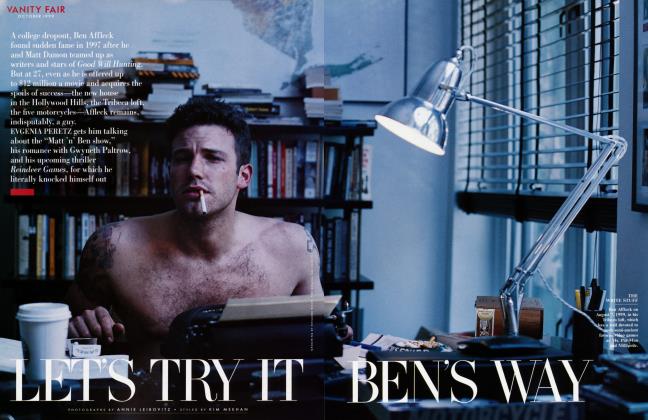

What Francisco Goya y Lucientes saw— and painted with an intense and urgent independence—made him the first truly modern old master. A pioneering visual reporter on the horrors of war and tyranny, he had the rare ability to express human pain, pleasure, and madness with equal power. In an excerpt from his forthcoming hook, ROBERT HUGHES recalls how, as a teenager in 1950s Australia, he heard the call of this long-dead Spanish artist and began his struggle to grasp the heroic sanity of Goya's vision

Goya never betrayed his deep impulses or told a pictorial lie.

Say the words "Spanish art" and four names at once leap to most minds: Velazquez, Goya, Dalí, and Picasso, with Doménikos Theotokopoulos, a.k.a. El Greco, a Greek artist who worked in Toledo, a close fifth.

For many people, El Greco is too pious and mannered to be wholly satisfying, while Picasso is too difficult to comprehend as a whole: his most popular works, from his Blue Period, are still his weakest, sentimental and derivative, while his greatest achievement, the co-invention of Cubism, remains too obscure to win an unrigged vote. The colossal popularity of Picasso flows from his protean energy and unquestionable genius. But it also represents the triumph of publicity over accessibility, of curiosity about the man over real love of his work. Much the same is true about Dali: a genius at publicity but ultimately a self-destructive one, an artist of extraordinary power in his youth—for nothing can ever diminish the marvelous poetry of his work in the 1920s and his film collaborations with Luis Bunuel—but a catastrophically self-repeating bore in his old age.

By contrast, Velazquez has next to no personal myth. We know so little about him that he almost vanishes behind his paintings—not at all an unhealthy situation in an age obsessed and blinded by "personality" and celebrity, but one that makes him difficult for people raised on late-20th-century ideas of artistic achievement to approach. What was he "really" like? We do not know and never will. No diaries, no letters, no self-disclosure: a seamless, expressionless, and polished mask that gives us virtually no grip on the paintings he made.

The most accessible of the four, it seems, is Francisco Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828). But even there, or perhaps especially there, one needs to be careful. It may be a cliche, but it is nonetheless true, that no great artist surrenders easily to the prying eye, and that none is altogether likely to be selfexplanatory. On the one hand, much of Goya's art has a revolutionary character.

On the other, Goyas that are not a bit satirical or hostile have been credited with subversive intent, and much of his work consists of portraits that, fairly seen, are not in the least derogatory of those who commissioned them. The idea of Goya as an artist naturally "agin' the system" is pretty much a modernist myth. But it is based on a fundamental truth of his character: he was a man of great and at times heroic independence, who never betrayed his deep impulses or told a pictorial lie. One of the abiding mysteries of Goya seems to be that so fiery a spirit, so impetuous and sardonic, so unbridled in his imagination, could ever have adapted not just occasionally but consistently, for more than 40 years, to the conditions of working for three successive Bourbon courts.

I had been thinking about Goya and looking at his works for a long time, off and on, before the triggering event that cleared me to write a book about him. I knew some of his etchings when I was a highschool student in Australia, and one of them became the first work of art I ever bought—in those far-off days before I realized that critics who collect art venture onto ethically dubious ground. My purchase was a poor second state of "Capricho" 43, El Sueno de la Razon Produce Monstruos (The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters), that ineffably moving image of the intellectual beset with doubts and night terrors, slumped on his desk with owls gyring around his poor perplexed head like the flying foxes that I knew so well from my childhood.

The dealer wanted £10, and I got it for £8, making up the last quid with coins, including four sixpenny bits. It was the first etching I had ever owned, but by no means the first I had seen. My family had a few etchings. They were kept in the pantry, face to the wall, icons of mild indecency—risque in their time—in exile. My grandfather, I suppose, had bought them, but they had offended my father's prudishness. They were the work of an artist vastly famous in Australia and wholly unknown outside it, a furiously energetic, charismatic, and mediocre old polymath called Norman Lindsay, who believed he was Picasso's main rival and whose bizarre mockoco nudes— somewhere between Aubrey Beardsley and Jean-Antoine Watteau, without the pictorial merits of either and swollen with cellulite transplanted from Rubens—were part of every Australian lawyer's or pubkeeper's private imaginative life.

That was what my adolescent self fancied etchings were about: titillation. Popular culture and dim sexual jokes ("Come up and see my etchings") said so. Whatever was on Goya's mind, though, it wasn't that. And as I got to know him a little better, through reproductions in books—nobody was exhibiting real Goyas in Australia all those decades ago; glimpsing El Sueho de la Razon was a fluke—I realized to my astonishment what extremity of the tragic sense the man could put onto little sheets of paper. Por Que Fue Sensible (Because She Was Susceptible), the woman despairing in the darkness of her cell, guilty and always alone, awaiting the death with which the state would avenge the murder of her husband. Que Se La Llevaron! (They Carried Her Off!): the young woman carried off by thugs, one possibly a priest, her little shoes sticking incongruously up as the abductors bend silently to their work. Tantalo (Tantalus): an oldish man, hands clasped, rocking to and fro beside the knife-edge of a pyramid in a despair too deep for words, and, across his knees, the corpse-rigid form of a beautiful and much younger woman whose passion cannot be aroused by his impotence. I could not imagine feeling like this man—being 14, a virgin, and full of bottled-up testosterone, I didn't even realize that impotence could happen, but Goya made me feel it. How could anyone do so? What hunger was it that I didn't know about but he did?

Excerpted from Goya, by Robert Hughes, to be published in November by Knopf; © 2003 by the author.

And then there was the Church, dominant anxiety of Goya's life and of mine. Nobody I knew about in Australia in the early 1950s would have presumed to criticize the One, Holy, Roman, and Apostolic Church with the ferocity and zeal that Goya brought to the task at the end of the 18th century. In my boyhood all Catholicism was right-wing, conservative, and hysterically subservient to that most whitehandedly authoritarian of recent Popes, Pius XII, with his foolish cult of the Virgin of Fatima and the Assumption. In Goya's time the obsession with papal authority, and the concomitant power of the Church, was even greater, and to openly criticize either in Spain was not devoid of risk. I remember how my Jesuit teachers (very savvy men) used to say, "We don't try to justify the Inquisition anymore, we just ask you to see it in its historical context"—as though the dreadful barbarity of one set of customs excused, or at least softened, the horrors of another; as though hanging and quartering people for secular reasons somehow made comprehensible the act of burning an old woman at the stake in Seville because her neighbors had testified to inquisitors from the Holy Office that she had squatted down, cackling, and laid eggs with Kabbalistic designs on them. It seemed to us schoolboys back in the 50s that, however bad and harshly enforced they were, the terrors of Torquemada and the Holy Office could hardly have compared with those of the Gulag and the Red brainwashers in Korea. But they looked awful all the same, and they inserted one more lever into the crack that would eventually rive my Catholic faith. So it may be said that Goya—in his relentless (though, as we shall see, already somewhat outdated) attacks on the Inquisition, the greed and laziness of monks, and the exploitive nature of the monastic life—had a spiritual effect on me and was the only artist ever to do so in terms of formal religion. He helped turn me into an exCatholic, an essential step in my growth and education (and in such spiritual enlightenment as I may tentatively claim), and I have always been grateful for that. The thought that, among the scores of artists of some real importance in Europe in the late 18th century, there was at least one man who could paint with such realism and skepticism, enduring for his pains an expatriation that turned into final exile, was confirming.

Artists are rarely moral heroes and should not be expected to be, any more than plumbers or dog breeders are. Goya, being neither madman nor masochist, had no taste for martyrdom. But he sometimes was heroic, particularly in his conflicted relations with the last Bourbon monarch he served, the odious and arbitrarily cruel Fernando VII. His work asserted that men and women should be free from tyranny and superstition; that torture, rape, despoliation, and massacre, those perennial props of power in both the civil and the religious arena, were intolerable; and that those who condoned or employed them were not to be trusted, no matter how seductive the bugle calls and the swearing of allegiance might seem. At 15, to find this voice—so finely wrought and yet so raw, public and yet strangely private—speaking to me with such insistence and urgency from a remote time and a country I'd never been to, of whose language I spoke not a word, was no small thing. It had the feeling of a message transmitted with terrible urgency, mouth to ear: This is the truth, you must know this, I have been through it. Or, as Goya scratched at the bottom of a copperplate in "Los Desastres de la Guerra": "Yo lo vi," "I saw it." "It" was unbelievably strange, but the "yo" made it believable.

We expect an artist to change in 30 years. But to change so much?

A European might not have reacted to Goya's portrayal of war in quite this way; these scenes of atrocity and misery would have been more familiar, closer to lived experience. War was part of the common fate of so many English, French, German, Italian, and Balkan teenagers, not just a picture in a frame. The crushed house, the dismembered body, the woman howling in her unappeasable grief over the corpse of her baby, the banal whiskered form of the rapist in a uniform suddenly looming in the doorway, the priest (or rabbi) spitted like a pig on a pike. These were things that happened in Europe, never to us, and our press did not print photographs of them. We Australian boys whose childhood lay in the 1940s had no permanent atrocity exhibition, no film of real-life terror running in our heads. Like our American counterparts, we had no experience of bombing, strafing, gas, enemy invasion, or occupation. In fact, we Australians were far more innocent of such things, because we had nothing in our history comparable to the fratricidal slaughters of the American Civil War, which by then lay outside the experience of living Americans but decidedly not outside their collective memory. Except for one Japanese air strike against the remote northern city of Darwin, a place where few Australians had ever been, our mainland was as virginal as that of North America. And so the mighty cycle of Goya's war etchings, scarcely known in the country of my childhood, came from a place so unfamiliar and obscure, so unrelated to life as it was lived in that peculiar womb of nonhistory below the equator, that it demanded special scrutiny. Not Beethoven's Muss es sein—"Must it be? It must be!"—written at the head of the last movement of his F Major String Quartet in 1826. Rather, "Can it be? It can be!"—a prolonged gasp of recognition at the sheer, blood-soaked awfulness of the world. Before Goya, no artist had taken on such subject matter at such depth. Battles had been formal affairs, with idealized heroes hacking at one another but dying noble and even graceful deaths: Sarpedon's corpse carried away from Troy to the broad and fertile fields of an afterlife in Lycia by Hypnos and Thanatos, Sleep and Death. Or British general Wolfe expiring instructively on the heights of Quebec, setting a standard nobly sacrificial death etiquette for his officers and even for an Indian. Not the mindless and terrible slaughter that, Goya wanted us all to know, is the reality of war, ancient or modern.

What person whose life is involved with the visual arts, as mine has been for some 45 years, has not thought about Goya? In the 19th century (as in any other) there are certain artists whose achievement is critical to an assessment of our own, perhaps less urgent doings. Not to know them is to be illiterate, and we cannot exceed their perceptions. They give their times a face, or rather a thousand faces. Their experience watches ours and can outflank it with the intensity of its feeling. A writer on music who had not thought about Beethoven, or a literary critic who had never read the novels of Charles Dickens—what would such a person's views be worth, what momentum could they possibly acquire? They would not be worth taking seriously. Goya was one of these seminal artists.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 324

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 289

The main reason that I started thinking about Goya with some regularity lay in the peculiar culture whose tail end I encountered when I went to live and work in America in 1970. It had almost been eviscerated of all human depiction. Of course it had plenty of human presence, but that was another matter. Here was America, riven to the point of utter desolation over the most bitterly resented conflict it had embarked on since the Civil War. Vietnam was tearing the country apart, and where was the art that recorded America's anguish? Well, there was art—most of it, with a few honorable exceptions like Leon Golub, of a mediocre sort, the kind of "protest" art more notable for its polemics than its aesthetic qualities. But in general there was nothing, absolutely nothing, that came near the achievement of Goya's "Los Desastres de la Guerra," those heart-rending prints in which the artist bore witness to the almost unspeakable facts of death in the Spanish rising against Napoleon, and in doing so became the first modern visual reporter on warfare. Nor did there seem to be any painting (and still less, any sculpture) produced by an American that could have sustained comparison with Goya's painting of the execution of the Spanish patriots on the third of May, 1808. Clearly, there were some things that moral indignation could not do on its own.

What did modernity lack that Goya had? Or was that the wrong question to ask? Was it rather that an age of mass media, our own age, so overloaded with every kind of visual image that all images were in some sense replaceable, a time when few things stood out for long from a prevailing image fog, had somehow blurred and carried away a part of the memorable distinctness the visual icon once had? Perish the thought. But the thought stuck. It would neither perish nor be resolved. Of course, Goya was an exception. It seems that geniuses (a word that, despite all the pecking and bitching of postmodernist criticism, must survive because there is no other that fits certain cases of human exception) are fated to be. But the fact that at the end of the 20th century we had (as we still have) no person who could successfully make eloquent and morally urgent art out of human disaster tells us something about the shriveled expectations of what art can do. So how could someone have managed it with such success two centuries earlier? There is no convenient answer, no wrappmg in which to package such a mystery, which is nothing less than the mystery of the tragic sense itself. It is not true that calamitous events are bound, or even likely, to excite great tragic images. Nearly 60 years after the bomb-bay doors of the Enola Gay opened to release Little Boy, and a new level of human conflict, over Hiroshima, there is still no major work of visual art marking the birth of the nuclear age. No aesthetically significant painting or sculpture commemorates Auschwitz. It is most unlikely that a lesser though still socially traumatic event, such as the felling of the World Trade Center in 2001, will stimulate any memorable works of art. What we do remember are the photos, which cannot be exceeded.

Goya was an artist wholeheartedly of this world. He seems to have had no metaphysical urges. He could do heaven, but it was rather a chore.

The angels he painted on the walls of San Antonio de la Florida, in his great mural cycle of 1798, are gorgeous blondes with gauzy wings first, and messengers of heaven's grace only second.

They would not carry such grace if they were not desirable. For him, it seems, God chose to manifest himself to humankind by creating the episodically vast pleasures of the world.

Goya was a mighty celebrant of pleasure. You know he loved everything that was sensuous: the smell of an orange or a girl's armpit; the whiff of tobacco and the aftertaste of wine; the twanging rhythms of a street dance; the play of light on taffeta, watered silk, plain cotton; the afterglow expanding in a summer evening's sky or the dull gleam of a shotgun's well-carved walnut butt. You do not need to look far for his images of pleasure; they pervade his work, from the early tapestry designs he did for the Spanish royal family—the majas and majos picnicking and dancing on the green banks of the Manzanares outside Madrid, the children playing toreadors, the excited crowds—right through to the challenging sexuality of The Naked Maja.

But he was also one of the few great describes of physical pain, outrage, insult to the body. At that, he was as good as Matthias Griinewald, the Master of the Isenheim Altarpiece. It is not at all inevitable that an artist is as good at pain as he is at pleasure. An artist can handle one without convincingly suggesting the other, and many have. Hieronymus Bosch, the 15th-century Netherlandish mystic whose paintings were so avidly collected by the gloomy Spanish monarch Felipe II and, enshrined in the royal collections, would in due course exercise such influence on the fascinated Goya, was not—despite the title of his most famous painting, The Garden of Earthly Delights— especially good at depicting the marvels of sensuality. His hells are always genuinely frightening and credible, his heavens scarcely believable at all. Exactly the opposite problem arises with his great Baroque antitype, Peter Paul Rubens. Look at a Rubens Crucifixion, that noble and muscular body hammered with degrading iron spikes to the fatal tree, and you hardly feel there is any death in it: its sheer physical prosperity, that abundance of energy, defies and in some sense defeats the very idea of torment. Rubens's damned souls are actors, howling their passion to tatters; one does not feel their pain, except as a sort of theological proposition.

The rhetoric overwhelms and displaces the reality (if one can speak of "reality" in such a context). But Goya truly was a realist, one of the first and greatest in European art.

Many people, myself included, think of Goya as part of our own time, almost as much our contemporary as the equally dead Picasso: a "modem artist." Goya seems a true hinge figure, the last of what was going and the first of what was to come: the last old master and the first Modernist. Now, it's true that in a strictly existential sense this is an illusion. No person "belongs" to any time other than his own. There are modernist elements in other artists, too; it's just that in Goya they are more vivid, more pronounced, than in his contemporaries. There is nothing "modem" about Anton Raphael Mengs, the top dog of painting at the court of Carlos III in Madrid. One could hardly make a case for the modernity of that wonderfully inventive and sprightly painter Giambattista Tiepolo, who just preceded Goya at the Spanish court. But the kind of modernism I mean is not a matter of inventiveness. It has to do with a questioning, irreverent attitude to life; with a persistent skepticism that sees through the official structures of society and does not pay reflexive homage to authority, whether that of church, monarch, or aristocrat; that tends, above all, to take little for granted, and to seek a continuously realistic attitude to its themes and subjects: to be, as Lenin would remark in Zurich many years later and in a very different social context, "as radical as reality itself."

You could say, for instance, that Goya was a man of the old world, because he was so clearly fascinated by witchcraft and absorbed by the ancient superstitions that surrounded the Spanish witch cult. These he illustrated again and again, not only in the monumental and fantastically inventive series of satirical prints known as the "Caprichos" but also in a number of his paintings, including the deeply enigmatic "Pinturas Negras," the Black Paintings, which he made to decorate the walls of his last Spanish home, the Quinta del Sordo, across the river from Madrid. You might say, then, that witchcraft was a continuous presence in Goya's imaginative life. But was it witchcraft itself that so fascinated him—the practice of enchantment, white and black magic acting upon reality, experienced by Goya as a fact of life in the real world—or was it the peculiarity of the social belief in it, distressing a rationalist artist as a vestige of a world that was better off without such superstitions? Affirmation or denunciation? Or (a third possibility) did he view witchcraft as a later Surrealist might, as a strange and exceedingly curious anachronism that bore witness to an unreformable, atavistic, stubborn, and hence marvelous human irrationality?

But he was also one of the new world that was coming, whose great and diffuse project the English called Enlightenment, the French éclaircissement, and to which the Spanish attached the name ilustración. This was the rationalizing and skeptical current of thought that had flowed across the Pyrenees and down into Spain. Its fountainhead was the writings of the Englishman John Locke. But its immediate influence on Spanish intellectuals came from France: from Montesquieu's Persian Letters (1721), from Voltaire, Rousseau, and Denis Diderot's gigantic Encyclopedia, that summation of 18th-century ideas, which appeared sequentially from 1751 to 1772.

Goya's friends were ilustrados, men and women of the Enlightenment. He painted their portraits, and those of their wives, children, mistresses. At the same time he painted people who were very much not ilustrados, representatives of the traditional regimes of Church and State, sometimes powerful ones. Goya tended to paint according to commission. There is little sign of ideological or patriotic preference in his choice of subject. Even a partial list of Goya's clients before the defeat of Napoleon in Spain shows a fairly even distribution of political views between conservative Spaniards, Spanish liberal patriots, and French sympathizers. In the first category, those he painted included the Duchess d'Abrantès, Juan Agustín Ceán Bermudez, the Conde de Fernán Nunez, Ignacio Omulryan, and of course Fernando VII. In the second, there were statesman Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, the actor Isidro Maiquez, and that fiery defender of Zaragoza against the French, Jose de Palafox. In the third, the priest Juan Antonio Llorente and the Conde de Cabarrus—not to mention that fierce ultra and Bonapartist, France's ambassador to Spain, the young Ferdinand Guillemardet.

But on balance he was certainly of the ilustrado party, and were there any doubt, it would be dispelled by his graphic works, especially the "Caprichos." Most of the Spanish artists who were Goya's contemporaries—Agustin Esteve, Joaquín Inza, Antonio Carnicero, and others—left no trace of opinions about society and politics in their work. They were craftsmen; they made their likenesses, did the job expected of them, and that was all. Goya was a very different creature; he could see and experience nothing without forming some opinion about it, and this opinion showed in his work, often in terms of the utmost passion. This, too, was part of his modernity, and another reason why he still seems so close to our reach, though we are separated by so much time.

About 30 years separate the two paintings that, between them, show the scope of the artist's career. Although their subject is the same, their mood and meaning, as well as the way in which they are painted, are utterly different. Yet they were painted by the same man: Francisco Goya y Lucientes. We expect an artist to change in 30 years. But to change so much? To remake himself from top to bottom, into so apparently different an artist, and with such compulsive force? Such a change can happen when youth turns to age, and sometimes art historians call it the coming of a "great, late style." It is radical, but not with the comparatively weak radicalism of youth. Coming as it does after a long life, when there is so little time left, it has a seriousness beyond mere experiment or hypothesis. It says: Look at this and look at it hard, because it may be the last you'll hear from me.

In each work he was painting the feast day of San Isidro, the patron saint of Madrid, where Goya lived. Each year it falls on May 15, and it is one of the city's biggest occasions for celebration and jollity. The person it commemorates was, according to legend (or hagiography, to be polite), an 11thcentury laborer who was tilling the soil in the meadows and flats beside the Manzanares, the river that gives Madrid its water, when his hoe struck a "miraculous" fountain in the earth, which thereafter never ceased to flow. Gradually, it became a place of pilgrimage; those who went there sometimes found that their diseases and infirmities were cured by drinking the water from San Isidro's well. In the 16th century a hermitage was built on the spot by Empress Isabel after her Hapsburg husband, Charles V (Carlos I of Spain), and their son Felipe drank the water and were cured of their illnesses. The hermitage became a church, which, expanded and remodeled in a neoclassical style in the early 18th century, still stands today, looking back across the Manzanares to the city. By the time Goya was born, in 1746, so many madrileños crossed the Segovia bridge each May 15 and converged on the slopes and meadows below the church of San Isidro that the spot had become a combination fairground, picnic ground, and religious gathering place.

They would come in their spring finery, the men in tricornes, breeches, and stockings, the women as delicate as butterflies with their parasols to ward off the sunshine, their carriages and barouches well furnished with picnic hampers; bowing and chatting to one another, passing compliments, and each swallowing a pious draft of holy water from the well.

This was the scene painted by Goya in 1788 in a brisk oil sketch almost small enough to have been done on the spot, en plein air, though it was almost certainly made in his studio from memory and pencil scribbles. Goya was then a man in his 40s, a late starter, his career scarcely even begun. Forty was not youngish for the time, but it was for Goya, who would defy all actuarial probabilities of the day by living to the age of 82. His picture is happy and festive. The people in it are those he wants to be among, those, you might feel, that he wants to be: the young man in the foreground, for instance, leaning forward on his cane, gazing with happy absorption at the bouquet of women under the elliptical saucer of the white parasol. Goya would like to be their friend, their social equal, their sexual partner. He would like to know the girl in the red jacket and the yellow skirt, who bends forward to fill the glass of a young man who leans forward to receive the drink. Goya's vision of this feast day of San Isidro is as uncomplicated and without strain as a Renoir boating-party scene. It is all decorum and shared pleasure.

In the distance, across the swiftly brushed gleam of the Manzanares, two big buildings look down on the merrymakers. One building has a single dome, the church of San Francisco; to the left of it is the Pardo, one of the various royal palaces in and around Madrid. Before long, Goya hopes, the scene he is painting will become the sketch for a huge full-scale preliminary study, or cartoon (meaning that the design was done on cartone, paper), which will then be woven in wool to mural scale—Goya meant it to be almost 25 feet wide—and placed in one of the rooms of the Pardo palace. He expects it to help bring him fame, and propel him on his trajectory of success, in the course of which he will become the chief court artist, First Painter to the King.

This did not happen in the way Goya hoped and expected. Later in the same year, 1788, the king—Carlos III, the Bourbon monarch of Spain—would die, and the Pardo palace would fall into disuse: no more new paintings and decorative schemes, including tapestries, would be done for it. There would be no full-size cartoon of the happy open-air crowds on San Isidro's day, and no tapestry based on such a cartoon. But the small sketch would be absorbed eventually into the collections of the great museum of the Prado, where it remains as one of the very few completely unshadowed images of collective social pleasure in Goya's work.

The second picture, traditionally titled The Pilgrimage to San Isidro, also hangs in the Prado, in the galleries reserved for what are called Goya's "Pinturas Negras," the Black Paintings of his old age. It was painted sometime between 1820 and 1823, when Goya was in his mid-70s and had only a few years left to live in Spain. (Before long he would leave the land where, except for a brief youthful sojourn in Italy, he had lived all his life, and move across the French border to Bordeaux, where he died in 1828.) A little earlier he had purchased a house outside Madrid, on the far bank of the Manzanares looking back at the city from roughly the same vantage point as the pilgrims to the miraculous spring of San Isidro. This new residence was the Quinta del Sordo, the Deaf Man's House. It drew its nickname, by mere coincidence, not from Goya himself, who was indeed as deaf as a stone by then and had been for decades, but from the previous owner, a deaf farmer. We have only an imperfect idea of what this two-story place looked like, since it was demolished later in the 19th century to make way for a railway siding, which now bears Goya's name. Goya, however, covered the internal walls with paintings, done in oil directly on the plaster. The Pilgrimage to San Isidro is one of these.

It is very big, indeed panoramic—4 1/2 feet high by 14 wide—though not as big as the tapestry was projected to have been 33 years before. It is also one of the few paintings from the Deaf Man's House that can be plausibly connected to an actual event, even though Goya did not sign, date, or title it. It may be that some other romeria, or pilgrimage, in some other part of Spain where Goya had been—Andalucia, for instance—supplied the inspiration for this picture. But the sight of the Madrid procession was right on Goya's doorstep, he had seen it year after year, and it is reasonable to suppose that the subject is indeed the veneration of San Isidro. That the painting, along with the others in the Deaf Man's House, should have survived at all is not far short of miraculous, for in 1873 the property was bought by Baron Frederic d'Erlanger, a wealthy Frenchman with real-estate interests in Spain. Unlike most of his developer confreres from then to now, d'Erlanger did care about the visual arts and thought that Goya's murals—bizarre, mostly incomprehensible, and almost illegibly dark—were worth saving.

Their existence had been noted before by Goya's friend Bernardo de Iriarte, who visited the house in 1868, long after Goya's death, and saw them on the walls, assigning his own brief titles to them. But it is more than possible that the Black Paintings might have perished through damp, vandalism, and neglect if the Baron d'Erlanger had not arranged to have the painted plaster—which was not true fresco but oil paint, and therefore highly vulnerable to everything that can go wrong with an absorbent, friable plaster surfacelifted from the walls and remounted on canvas. This work began in 1874. In the process, a certain amount of editing and "correction" went on at the hands of the restorer, one Martin Cubells: for instance, early (pre-restoration) photos suggest that the horrific main figure in Saturn Devouring His Son had a partly erect penis before Cubells toned it down in the interest of public decency. It seems extraordinary, when you think of it, that a penis (erect or not) could have been considered more offensive to public taste than the spectacle of a cannibal father ripping a long red gobbet of meat off the corpse of his dead child; but who can say that the same fatuous censorship might not be inflicted on it today?

D'Erlanger had the remounted Black Paintings shipped off to Paris to be shown at the Exposition Universelle of 1878. One would like to report that they caused a sensation, but they did not. Journalists who mentioned them at all dismissed them as the work of a Spanish madman, although they were very much admired by some of the Impressionist painters who saw them. Goya was not a famous figure in France, not even then, but cognoscenti like Manet and Delacroix greatly admired him on the basis of his prints, which were becoming quite well known, and the Black Paintings revealed an aspect of Goya even more extreme, imposing, and bizarre than was to be found in his small-scale graphic work. Still, their display in a corridor next to an ethnological exhibition half a century after Goya's death did not attract much attention, and in 1881 the baron sent the Black Paintings back to Spain, giving them to the Prado.

The new Pilgrimage to San Isidro is the reverse of the old one in every way. It is dark, near hysterical, and threatening, without the smallest trace of the sweet, festive qualities of the old design. The colors are funereal: browns and blacks predominate, with only an occasional trace of white. The painting contains no picnickers, parasols, or pretty girls. What it shows instead is a sluggish snake of thoroughly miserable-looking humanity crawling toward the viewer across an earth as barren as a slag heap. Two or three women are visible, but most of the people in the painting, insofar as their gender can be made out at all in the enveloping gloom, are male. The most clearly distinguishable woman is pushed off to the right, her face in profile, a mask of lamentation. No picnic baskets, glasses, or other props of plein air enjoyment are to be seen.

As it reaches the picture plane, the serpent of Goya's human misery rises up and expands like the hood of a cobra, and we see what it is made of: faces, every one of them contorted in a rictus of extreme expression, singing out of key together, some of them (one feels) just howling like dogs or monkeys. Mouths like craters, mere black holes, a visual cacophony of darkness giving vent to itself.

In this mound of humanity, some divisions of class can be seen. A pair of male figures, whose faces are sunk in the gloom, can be identified as middle class by the cylindrical black hats they are wearing. But the spearhead of this human mass is proletarian, or less than that: mendicants and would-be ecstatics in rags, utterly absorbed in a vision that we, as onlookers, cannot identify or share. The guitarist in the foreground is so caught up in his praise song, or raucous cante jondo, or whatever it is, that he seems beyond communication.

This is Goya's vision of humanity in the mass, in the raw, almost on the point of explosion. It is painted in a way that seems to have no precedent, fiercely and with a broad brush: swipes of ocher and umber, deep holes of black, the forms of nose, cheekbone, forehead, ear, and the sunken eye socket with the dangerous-looking highlight inside it forming themselves, as it were, out of the rough paste of paint.

No earlier artist had conveyed the irrationality of the mob, especially the mob inflamed by a common vision—religious, political, it makes no difference—with such unsentimental power. What is more, the expressive roughness of the paint, the urgency with which it is applied, and the theater of expression on the crowd's individual faces—angry, stupefied, cunning, close to madness—amount to an assault on silence. Which they collectively are. They have the ferocity of creatures trying to make themselves heard from the other side of a sealed glass. They are the creatures of Goya's own deafness. They jostle at the surface of the painting, but the artist cannot hear them and never will. Hence the violence of his representation, the caricatural will to make audible what will always be silent to him.

Goya did not win international fame in his lifetime, or for many years after his death. In the late 19th century, a succession of French, English, and German artists based their aspirations as realists on their enthusiasm for Velazquez; gradually, for some, Goya's work then took over as a standard and model. (The two were not mutually exclusive, of course; Manet was only one of a number of major painters who adored them both.) From about 1900 on, Goya was one of the very few old masters—and a recent old master at that—to be exempt from the polemical rejection of the past felt by many younger artists. He was, in a real sense, the last old master; and in an equally real sense, the first of the Modems.

Yet when he died, none of that would have made sense. He had few admirers and, what is even more surprising, practically no imitators anywhere in Spain. He lived in exile and obscurity, in France. Liked by the Bourbon king Carlos III, loved by his son Carlos IV, Goya was not liked a bit by the next Bourbon, Fernando VII, who was restored as king after years in exile, having been thrown out by Napoleon's occupation of Spain between 1808 and 1814. Fernando suspected Goya of disloyalty and in any case preferred the stiffer, smoother neoclassical manner of his own chief court painter, Vicente Lopez. After 1815, after Goya had served the Bourbons as chief painter for so long, it was as though he had gone into eclipse, his great etching series mostly unpublished (the fate of the "Desastres de la Guerra" and the so-called "Proverbios," or "Disparates") or lapsed into semi-obscurity (as happened to the "Caprichos"); his drawings unknown; his paintings scarcely visible to the public except for three pictures in the Prado, two of which were royal portraits of Bourbon monarchs he served, Carlos IV and Queen Maria Luisa. (Today, apart from drawings and prints, the Prado owns some 150 of his pictures, though not all are genuine, a fact that its curators will sometimes admit to in private without wishing to go on the record about it. A striking example is the Milkmaid of Bordeaux, a painting done very late in Goya's life, which is accepted with joy by everyone who doesn't know his work well and rejected by most who doincluding the curatorial staff of the Prado, who cannot yet take the risk of demoting such a popular picture.)

Outside Spain, he was just as poorly known. A set of his fiercely moralizing "Caprichos" was offered by a London bookseller in 1814 for £12; a few years later, nobody had bought it, and its price was reduced to seven guineas. Britain's National Gallery did not acquire any Goyas until 1896, and in a famous fit of moral hysteria the greatest art critic of his age, John Ruskin, actually burned another set of "Caprichos," as a gesture against what he conceived to be Goya's mental and moral ignobility.

Such an idea seems very odd today; if nothing else could make you sense that Ruskin was cuckoo (and he was; as mad and depressed in old age as King Lear himself), this peculiar deed would. Yet it is not entirely out of keeping with common, popular images of Goya, all of which turn out, on inspection, to be false; invented, mistaken, or the result of accretions of legend. It was not so long ago, for instance, that most people who thought about Goya considered him mad. The assumption was based on Goya's deep interest in insanity, which can readily be deduced from some of his "Caprichos," from the indisputable fact that he painted a number of madhouse scenes and was almost the first European artist to do so, and from the dark, enigmatic paintings that adorned his last home in Madrid, the Quinta del Sordo. But this is illogical. It is like saying Hieronymus Bosch was possessed by the Devil because he painted such vivid and influential images of hell.

Goya was fascinated by madness for two reasons. The first was that he shared the general interest in mental extremity that characterized Romanticism in European art. What was the human mind capable of when at the end of its tether? What images would it throw out, what behavior would it release? In this sense, Goya was no more mad than Shakespeare when he wrote the "mad scenes" for Lady Macbeth and Ophelia, and created the sublime, terrible, and fragmented utterances of Lear. Almost all the great artists of Goya's time, from Fuseli to Byron, were fascinated by madness, that porthole into unplumbed depths of character and motive. Goya was in some ways the greatest of all delineators of madness, because he was unrivaled in his ability to locate it among the common presences of human life, to see it as a natural part of man's (and woman's) condition, not as an intrusion of the divine or the demonic from above or below. Madness does not come from outside into a stable and virtuous normality. That, Goya knew in his excruciating sanity, was nonsense. There is no perfect stability in the human condition, only approximations of it, sometimes fragile because created by culture. Part of his creed, indeed the very core of his nature as an artist, was Terence's "Nihil humanum a me alienum puto, " "I think nothing human alien to me." This was part of Goya's immense humanity, a range of sympathy, almost literally "co-suffering," rivaling that of Dickens or Tolstoy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now