Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Creeks Revisited

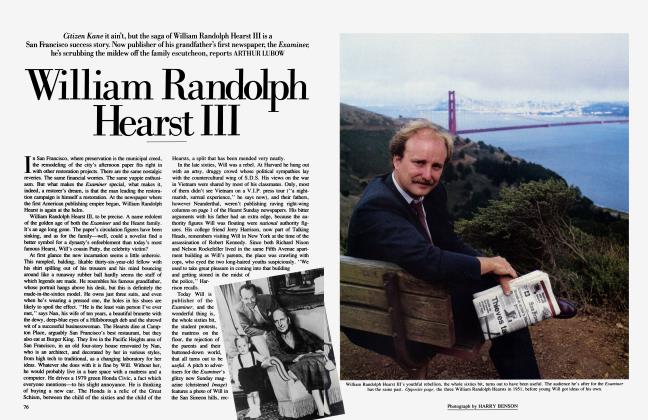

Part William Randolph Hearst, part Andy Warhol, part Morticia Addams, the Creeks was home to dancer Ted Dragon and the late eccentric Alfonso Ossorio— and the scene of some of the best bashes of East Hampton's bohemian past. Now the property is up for sale, for a cool $25 million. ARTHUR LUBOW reports

ARTHUR LUBOW

To try to grasp the Creeks, forget for a moment that it is a house—that it is, indeed, the final intact estate from a time when East Hampton was a bucolic Long Island farming and fishing village, not yet devoured by its colony of rich summer people. Imagine instead that this black stucco mansion with its coppertiled roof, brooding over fifty-seven acres at the head of Georgica Pond (by whose banks Steven Spielberg, Calvin Klein, Arnold Glimcher, and Robert Benton encamp for the summer), is an art object, like Kurt Schwitters' Merzbau. You will be better prepared for the phantasmagoria that assaults you behind the red-andblue front door. Perhaps, knowing the vagaries of the art market, you will also be more philosophical when you discover that the property is up for sale at an asking price of $25 million.

The Creeks is vertiginous proof that too much is not enough. Taken half as far, it would be vulgar. Instead, it is mind-boggling. Most of the walls inside are black like the exterior stucco, but little wall is visible. The house is covered and crammed with things, some precious, some tawdry. The doubleheight salon is typical. It contains an eight-foot-high New Hebrides slit-gong, two huge curved tusks, two sawfish snouts on sterling mounts and two tall Venetian lanterns, a piano and a harp, a Texas-longhom chair draped with African beads, small paintings by Jackson Pollock and Jean Dubuffet, two Chinese bronze dragons, a small Eastlake curio cabinet, an African wooden figure that was a gift from Paul Tillich, a crystal chandelier from a Greek Revival town house in Greenwich Village, and a Chinese opium bed. On one wall is an assemblage by Alfonso Ossorio that, in its juxtaposition of the colorful and the grotesque, rivals the surrounding decor. Until his death at seventy-four from a stroke in December 1990, Ossorio was the presiding genius of this place. On other walls, colorful but far less conspicuous, are needlepoints done by Ted Dragon, Ossorio's companion of forty years and now his sole heir.

They were an odd couple, Alfonso and Ted. Ossorio was a polymath fluent in six languages, with an intimidating facade of lacquered manners. Dragon, a former ballet dancer, is breezy, chatty, and outgoing. Ossorio favored navy blazers or dark suits; Dragon is known for his caftans and elaborate costumes. Alfonso, a lapsed Catholic, would work late into the night, while Ted wakes up at dawn and attends a daily 7:30 A.M. Mass. Ossorio avoided the gay scene, but Dragon has always had a large circle of homosexual friends. "A week would go by and I wouldn't even see him," says Dragon, seventy-one. "We had a very, very good relationship, very healthy. We were both independent. Lovebirds in a cage kill each other. I had two pairs. They will get along beautifully for years. They'll follow each other around, cooing. But one day, one is on the bottom, dead with a cut throat. Then a month later the other one dies of a broken heart."

The Creeks was capacious enough to house two men of varying tastes, and, beyond that, to furnish a backdrop for the modem minuets of a unique community. During the fifties, East Hampton was home to Pollock and Lee Krasner, Willem de Kooning, Clyfford Still, Robert Motherwell, John Little, Clement Greenberg, and Harold Rosenberg. In this artistic capital, the Creeks shone supreme as a gathering spot for the elect. Unlike the other artists, Ossorio was very rich, from a family-owned (Continued on page 193) sugar refinery in the Philippines. He was generous, he was courteous, and—like all great party givers—he was shy. He preferred observing to being observed. He became the consummate host of the Abstract Expressionists, throwing parties that almost forty years later still evoke nostalgic sighs.

(Continued on page 193)

(Continued from page 152)

The most famous story of a Creeks party concerns a no-show. There was a musical evening at the Creeks on the night of August 11, 1956, at which Pollock was expected. By this time, the man dubbed by Life seven years earlier as arguably the greatest living American painter was rotten with drink. His wife, Lee Krasner, had fled his abuse on a solo visit to Paris, confiding to Dragon that she wanted a divorce. "I told her to wait, to think about it while she was away," Dragon remembers. "I knew the man was going to destruct." Drunk, Pollock called the Creeks from a bar to say he would be late for the party. He never made it. In an alcoholic fury, he drove his Oldsmobile off the road at top speed, and his head was crushed against a tree. The musical evening proceeded on schedule. The audience never knew.

It was Pollock and Krasner who had brought Ossorio and Dragon to East Hampton originally. At Pollock's second show at the Betty Parsons Gallery in January 1949, Ossorio bought a large drip painting, Number 5, 1948. When the painting was damaged in delivery, Pollock offered to repair it. Ossorio and Dragon drove out and stayed overnight with Pollock and Krasner in Springs, a section of East Hampton. They were impressed by its beauty. Returning to pick up the canvas a month later, they rented the large Helmuth house on posh Jericho Lane for the summer. It was a wonderful place for a painter. But for a dancer?

They moved instead to Paris, Ted dancing with the Paris Opera Ballet, Alfonso painting. When, a year later, the Pollocks cabled from East Hampton that the Creeks was for sale, Ossorio considered how best to pose the question to Dragon. ''If I get it, will you break your contract and go back?" Ossorio asked him. "You've had your career and you're a first dancer. Stop at the top. You haven't seen the place, but you'll love it." Dragon thought it over for a week. "I didn't want the feeling of being the kept little thing on Georgica Pond," he explains. But he agreed.

On the ocean-liner voyage (the way people traveled from France to New York in 1951), Ted bought a set of Ile-deFrance souvenir ashtrays. "Do you want to see?" he said to Krasner as she drove him out for his first peek at the Creeks. "I've started to buy things for the house." When she saw the kitschy ashtrays, she laughed and laughed and laughed. "Ted," she said, "you have no idea."

The Creeks was a moldering mansion that had been built in 1899 by Grosvenor Atterbury, the architect of some of the grandest Southampton summer cottages. For this project, Atterbury had unusual clients: an extravagant artistic couple, Albert and Adele Herter, who painted society portraits for handsome fees and decorated fashionable homes at even greater profit. In the Creeks, Atterbury combined the grandiosity of wealthy Southampton with the bohemian pretensions of East Hampton. The house's green roof alluded to the then fashionable Orient, as did the Chinese temple front that was reassembled on one wall of the double-height salon, a room in which Adele—dressed in embroidered robes and surrounded by cut dahlias—enjoyed hosting tea parties. The house was designed for elaborate entertaining. When Ossorio first saw it, however, it had been uninhabited for several years. "You had the feeling that if you touched the wall your hand would come back wet," says Pollock biographer Jeffrey Potter, who saw the Creeks at that time. "It was like a catacomb. It spoke to me of death and depression." Ossorio bought it for $35,000.

Then he emptied it. The house was full of stuff—from the canned goods in the cellar (the Herters had operated a working farm) to the Wagnerian costumes in Albert's studio, a grand building that doubled as a theater for amateur dramatics. There were many old paintings, including some full-length portraits that Ossorio gave to Pollock, who admired the shape of the canvases. Beneath some of the celebrated Pollock drips, Dragon says, an Xray eye might detect a Victorian dowager.

In the same missionary spirit, Ossorio and Dragon converted their late-nineteenth-century house into a contemporary showplace. The Herters had painted the interior Chinese red, imperial gold, and a robin's-egg tint known as Herter blue. Ossorio and Dragon whitewashed it. They covered the floors with gray carpets, and scattered a few potted bamboos and Oriental rugs in strategic places. They created, in short, a residence that was a modernist gallery, the perfect place to display their growing collection of paintings by Pollock, Dubuffet, Still, and de Kooning.

Since Ossorio was preoccupied with his art, Dragon managed most of the entertainment. "Ted wants to be sure that in this house you have the right hors d'oeuvres, the right flowers," says a friend, landscape designer Harry Acton Striebel. "The fountains had to be on. The iced tea had to have fresh mint. The lemons had to be served on a dish with a pedestal. The almonds he would roast before every cocktail party in kosher salt." Yet at the lavish dinners for which the Creeks became known, Ted often failed to appear. Confident that every detail of the menu was in place, having set the table as he liked with overflowing fruit bowls and tosses of candied violets and other delicacies (a style he said he had borrowed from Marie Antoinette), he would vanish in the wings. Where was he? Who was he? In the early years, awed by Alfonso's wealth and erudition, many visitors found Ted to be a mystery—a mystery not worth pursuing.

They had met in the Berkshires in a scene out of a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta: Alfonso was sketching on an easel in a meadow when Ted passed by, picking flowers. It was 1947, and Ted was at Jacob's Pillow studying on scholarship with Ted Shawn. Having discovered the world of ballet by chance as a teenager in the Northampton, Massachusetts, Y.M.C.A., Edward Dragon Young had used dance as an exit visa from his working-class Catholic family to the brighter circles of New York. At a Broadway audition, Agnes de Mille asked his name, and he told her. "Throw the Young out," she declaimed. He was Ted Dragon from then on.

Although he had seen a lot since leaving Northampton, Dragon had never met anyone like Ossorio. Crisply elegant with mandarin manners, the young Ossorio had a polished, exotic beauty. "He had mannerisms as well as manners," recalls art critic B. H. Friedman. "He'd say, 'As you know, Bob, the Merovingians had a very different sort of weapon from the soand-sos,' or 'As you've read in Baudelaire's letters. . " The more one got to

know him, the more impressive he became. He seemed to know everything, from the intricacies of the Latin Mass to the arcana of British royal genealogy to the habits of aboriginal tribes—the list could go on and on. "What drew me to Alfonso was his mind," Dragon says. "In the ballet when all you talk about is the metatarsal and the elbow joint, it would make me so angry. I thought there must be something more."

Bom in Manila, the fourth of six sons of a Spanish father and half-Chinese mother, Ossorio was educated in Catholic boarding schools in England and the United States before graduating from Harvard. In 1940 he ran off to Taos, New Mexico, with a redheaded divorcee, Bridget Hubrecht. They were married in early 1941, but by year's end the marriage had dissolved. A couple of other momentous events occurred at about the same time: Ossorio had his first one-man show in New York, and the United States entered World War II. Ossorio, by now a naturalized American citizen, enlisted in the army; before he could report, however, he was hit by a taxi on Madison Avenue, suffering a badly broken leg. Two years elapsed before he joined the service, as a medical illustrator. The delicate drawings he made of bloody surgeries typify Ossorio's youthful work: fastidious treatment of grotesque, surreal subjects. (Ossorio's early pictures will be the subject of a show at the Whitney Museum in New York later this year.)

The move to the Creeks in 1952 gave Ossorio more space to work and to exhibit his collection. Along with his Pollocks, he by then had many Dubuffets and several important Stills. The effect of these artists on his own work was increasingly obvious. His painting became less illustrational and more fluid. His preoccupation with violent colors, surface texture, and allover design revealed his sympathy with Abstract Expressionism. On a personal level, he formed an unlikely friendship with Pollock. The brooding, tongue-tied westerner would appear to have had little in common with the wealthy, well-educated Ossorio. Maybe that was the secret. "There couldn't be two people more different than Pollock and Ossorio," says B. H. Friedman, who has written biographies of both men. "But I think there was mutual respect and not much grounds for competition."

When not producing art of his own, Ossorio was busy advancing the work of others, traveling frequently to New York and Europe. In the late fifties, East Hampton during the winter was still very much a rural village. Left alone for long stretches, Dragon became morose and resentful. He had given up his dance career, and for what? To become, as he had feared, the kept little thing on Georgica Pond. "It was a terrible jolt to come from being a star in the Paris Opera—une etoile—and all that color in my life," he recalls.

About the only excitement in the Hamptons those winters came from reports of odd burglaries of valuable antiques from empty summer houses. For four years, Chippendale mirrors, Ming vases, and Oriental rugs disappeared mysteriously from the unguarded estates. It caused quite a stir in February 1959 when the East Hampton chief of police just happened to see a man emerging from the window of Pan Am founder Juan Trippe's house near Georgica Pond. Ending the string of burglaries, the policeman arrested Ted Dragon.

It had started as an impulse. In 1956, passing the Helmuth house (then owned by art dealer Leo Castelli) as he exercised his two standard poodles, Ted noticed the door ajar. He walked in. It was so easy. That would be the pattern over the years. He never broke into a house, and he never sold the things he stole. Some pieces he gave away. Others he displayed, telling Alfonso they had come from Northampton relatives. Most of the booty landed in the attic of the Creeks. "That attic, you couldn't move," Dragon says. "I had a lot of it restored and reupholstered. Afterwards, everyone was very nice about it. A woman in Sag Harbor said, 'I never would have thought to put rose and gold on that Empire set.' "

Following Ted's arrest, Ossorio obtained the services of Dr. David Abrahamsen, a psychiatrist specializing in criminal insanity. With the help of Abrahamsen's testimony (which cost a Pollock and a Dubuffet), Dragon received a suspended sentence provided he undergo psychotherapy. Ossorio supported him without flinching. As B. H. Friedman recalls, "Alfonso said, 'Bob, you mustn't ever think this was one of my charities. This was an act of love.' Alfonso could have washed his hands of Ted. There was nothing that Ted could have done that would have humiliated Alfonso more." Recognizing that he, and not the other absent homeowners, was the true target of these irrational thefts, Ossorio became more responsive to Dragon. And thanks to therapy, Dragon grew more independent. "It cemented our relationship," Dragon says. "How could you ever turn on a person who has stood by you that way? I would say that episode saved my life and let this whole thing be created here at the Creeks. It was too much maybe for me, this house. But it put it all in focus."

In the early sixties, Ossorio cut back on the New York excursions and spent more time in his studio, working on three-dimensional assemblages that he called "congregations." On shingles or pieces of plywood, he mounted the flotsam of nature and civilization—glass eyes, ropes, horns, bones, hypodermic needles, mirrors, pottery shards, driftwood, rotted fruit—and then embedded these elements, often brilliantly colored, in clear plastic. Little at the Creeks was wasted. "Every soup bone was boiled in ammonia and dried out in the sun," Dragon says. "I was always losing things. . .. If I'd see a vase gone, I'd know it was smashed and in a picture." One of Ossorio's favorite substances was something he called "end-of-the-day plastic"— a modem equivalent of the color-streaked end-of-the-day glass that was produced in Victorian factories after the evening whistle blew and the remaining bits were tossed into a melting pot. Made in the same fashion by manufacturers of colored telephones, end-of-the-day plastic was just the sort of stuff Ossorio appreciated: humble in origin, viscously sensual, ambiguously evocative. Out of such glittering trash, the artist assembled complex pieces, often with religious themes. Indeed, the whole enterprise of sanctifying cast-off materials in mosaic-like works of art had religious overtones. As gaudy as the floats in a Mardi Gras parade, Ossorio's congregations wound up in a few museum collections, but repelled most critics. "Someone once said they resembled what was left after cannibals had feasted on Balkan royalty," Grace Glueck quipped in The New York Times.

The failure of his work to catch on with the public and his doctor's admonition to exercise drew Ossorio out of the studio and into his garden. Under the Herters, the garden of the Creeks had been shaped by the fussy taste and cheap muscle of the Victorian period. Many of the beds were plain ivy or pachysandra, empty stages waiting for performers. "I want tomorrow for the garden to be blue," Mrs. Herter might say, and the summer staff of thirty Japanese gardeners would snip blue blooms, insert them into vials, and thrust them overnight into the beds. Ossorio and Dragon tore out a rose garden, which had absorbed one gardener's full-time attention. They removed the Concord-grape vines from the porte cochere, eliminating the need to sweep the doorway three times daily in autumn. And gradually, both to minimize maintenance and to create a garden that would be attractive year-round, they began cultivating evergreens.

In the early 1970s Ossorio turned the full beam of his intelligence on the garden. He was an obsessive researcher. The library at the Creeks contains some 15,000 books, ranging from liturgy to pornography: Ossorio would thumb through catalogues, ordering books by the boxful, reading a volume or two a night. When he became interested in wine, for instance, he learned all he could about the vineyards of Bordeaux, acquiring a distinguished cellar in the process. Fascinated by food, he devoured cookbooks like novels. "In the long winter months, when people said, 'What do you do?'.. . My God! I was chopping!" Ted jokes. Ossorio's affluence, obsessiveness, and eccentric taste lent a tinge of unreality to all of his endeavors, including his fondness for cooking. "One of the last things he discovered," Ted reports, "was a tenderloin of pork marinated for three days in a bottle of Chateau d'Yquem and prunes." (Before requesting the recipe, you perhaps should know that Yquem, even in weak vintages, sells for more than $100 a bottle.) Journalist Patsy Southgate recalls that the Creeks, with its artwork of horns and eyeballs, was the first place she ever tasted a stuffed heart. "It was just the right thing to serve in that atmosphere," she says. "You wondered whose heart it was."

So when he took up evergreens, Ossorio was unlikely to settle for the yews and junipers of his East Hampton neighbors. The weirder the specimen, the more he wanted it. Because Georgica Pond has a changing shoreline, he constructed a very expensive and controversial retaining wall to keep the water out. To pay for it, Ossorio and Dragon sold a Pollock masterpiece, Lavender Mist {bought in 1950 for $3,000), to the National Gallery in Washington for $2 million. Over Ossorio's final two decades, he parted with much of his collection to pay his gardening bills. "There was always plenty to live on and keep the place going in a normal way," Dragon says. "But Alfonso would spend $300,000 in three months on trees. There's about $4 million of trees out there."

Ossorio designed the concrete and metal sculptures, mostly in bold red or blue, that punctuate the garden. His primary interest, however, was in the plants themselves, and he arranged them like sculpture, directing cranes to lift, tilt, and move them until he was satisfied with their placement. Ignoring all rules of landscaping, he clumped trees of contrasting shapes and colors in groups that looked neither natural nor formal. One weeping white pine was trained to resemble a dinosaur. Three spruces—green, blue, and yellow—were grafted together into one tree. Ossorio loved the weeping, the contorted, the fastigiate, the varicolored, the purple, red, and yellow—all that refined gardening taste usually eschews. In his plantings, as in his art, refined taste takes a backseat.

To set off the colors of the garden, Ossorio and Dragon painted their stucco house black, with red, blue, and white trim. They made their oval swimming pool black as well (perhaps starting the trend that has since swept Long Island). So it was a natural progression to paint the interior walls of the house black and to replace most of the Abstract Expressionist paintings (which were needed to pay for the trees, anyway) with Ossorio's own congregations. "I got the idea from a jewel box, ' ' Dragon says. "When you want to see a pin or a string of pearls in a jewelry store, they pull out the black velvet cushion. Everything looks fabulous set off against black. We painted the house black and suddenly everything started to look better. ' '

By the time of Ossorio's death, the Creeks—inside and out—had become the artist's ultimate congregation. "His greatest work is the whole Creeks," Dragon says modestly. "All I did was go along and embellish." And it is true that, while Dragon acquired most of the furniture in the house and kept the place running, Ossorio molded it all to his peculiar aesthetic. Precious and tawdry, delicate and crass, old and new, the Creeks is a constant juxtaposition of forms that refuse to meld. Ted himself—especially when decked out in a caftan, sandals, and African beads—fits right in. "You're like one of my pictures walking out of the house," Alfonso would tell him with delight. Ted could carry it off self-confidently because he knew that behind him, in blue coat and Harvard tie, stood Alfonso. Indeed, it wasn't just Ted himself, in his gaudy multi-ethnic attire, who resembled a congregation. More fundamentally, it was Ted and Alfonso together: so opposite in every surface aspect, yet bonded together in the antithetical, unifying spirit of Ossorio's art.

Which may explain why, with Alfonso gone, Ted is eager to sell the Creeks and start a new phase of his life. Although he vows that the property will not go to developers, the Creeks will surely take on a new character under different owners. (Barbra Streisand is on the shortlist of prospective buyers.) As for Ted, he hopes to build a new house that will reproduce his favorite rooms at the Creeks: a large entertaining area, a bedroom, a study, and a big kitchen. "It will be a hollow square with a fountain in the middle and no grounds," he says. "The woods will come right up to the edge. And away from the water—I'm sick of looking at it." Strong as their personalities were, the house's personality was stronger, and Ted and Alfonso were inevitably known as the men who lived at the Creeks. Dragon thinks it may be time to stop residing in a work of art, and to start living in a house that is simply a house.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now