Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Bernini of L.A.

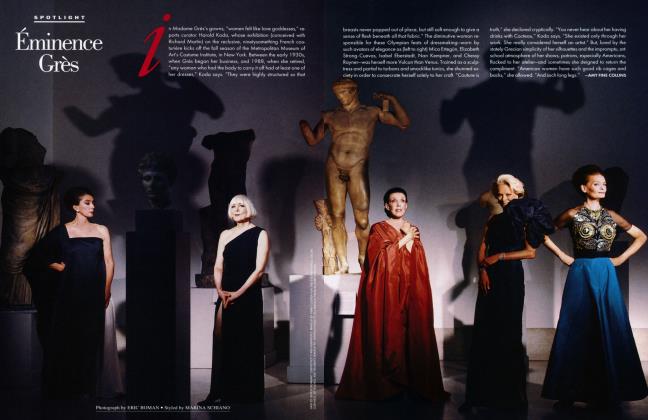

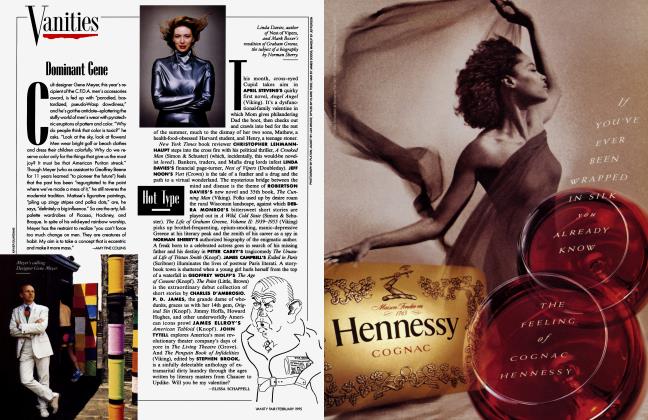

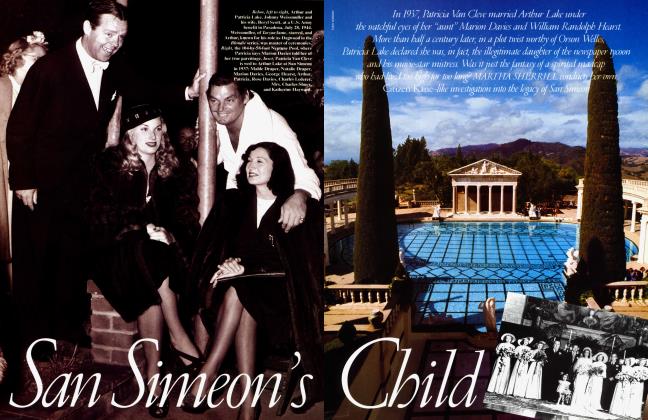

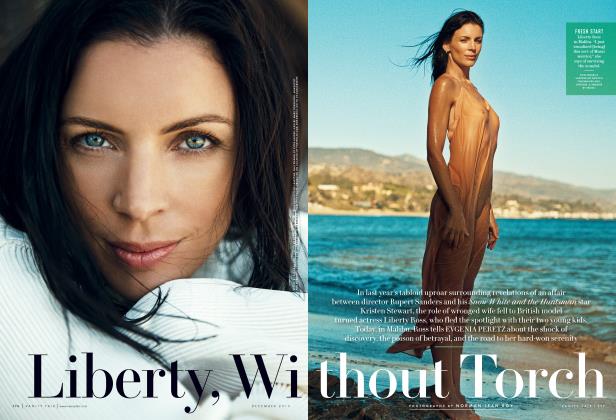

Mexican-born sculptor Robert Graham has unexpectedly become L.A.'s Renaissance man for the nineties, with public works, private commissions, and even an urban-revitalization plan for his home base, Venice Beach. And with total synergy, he's also married to Hollywood's newly emergent power, Anjelica Huston. AMY FINE COLLINS reports

AMY FINE COLLINS

It's a late-May dusk in Los Angeles, and sculptor Robert Graham, a large and graceful man with a wavy mane of silver-shot hair, is settling into the banquette of a nearly empty Venice Beach restaurant for an early dinner. He will not linger long, as he is eager to keep an appointment with his fiancee, Anjelica Huston, whom he will marry over Memorial Day weekend. Graham speaks so softly—his words seem more like cognition than conversation—that I repeatedly lean closer to hear him. Suddenly a woman at a nearby table disrupts the cafe's tranquillity by demanding that Graham be asked to extinguish his Havana cigar— probably his sixth of the day. But the restaurant's proprietor does not heed her request. Venice is Graham's turf. He is one of its most visible denizens, and everyone in the funky beachfront community—from maitre d's to cops —knows that wherever their sculptor-in-residence goes, a trail of pungent cigar smoke will surely follow. Earlier, Graham showed me the architectural model for his arcaded, Venetian-style studio/ house complex, which in another two years will rise—like a New World Doge's Palace—fifty-five feet high on Windward Avenue.

(Huston has not yet decided whether she will abandon her Beverly Glen house, forty-five minutes away, to live there fulltime with him.) Like all the projects the sculptor takes on, it's a dizzyingly ambitious scheme. In the fashion of a Gothic cathedral, it will be a work involving a number of artists and craftsmen collaborating over an undetermined period of time. Graham expects the building to do more to revitalize the community than any official urban-renewal plan.

Though he presides like a padrone over Venice—and over the L.A. art scene—Graham still seems a bit of an anomaly here. Not only is he smoking an aggressively thick cigar, he is dining on sanguine roast beef, which he delicately wraps in a corn tortilla, and is drinking tequila. He is dressed in a refined variation of California-casual attire—a white shirt open at the neck and putty-colored chinos held up by an alligator belt. A brooding Mexican-American in a land renowned for blonds and bimbos, he is inward, dark, and guarded. Even his anatomical makeup is incongruous. As Huston tells me the next day, "he has large, manly shoulders, but fine, beautiful hands."

They are sculptor's hands, of course, accustomed to modeling in clay or wax the supple surfaces of the nude female body. Which leads to another paradox about Graham: when hardly a single other respected artist is working in a representational style, he persists in making realistic, figurative sculptures—contemporary idols—using the painstaking technique of bronze casting. In the context of Julian Schnabel's hulking fecal sculptures, Richard Serra's menacing Minimalist monuments, and Claes Oldenburg's goofy overgrown Pop objects, his naturalistic, miraculously skillful nudes look so old-fashioned they seem subversive. He is a Rodin, a Donatello, an academic apres la lettre—and he's good enough to get away with it. What's more, Graham, who represents himself in L.A. and is affiliated with the Robert Miller Gallery in New York, avoids the usual round of gallery and museum shows. "They're senseless displays of wares for the trade," he says dismissively. Instead, a latter-day Saint-Gaudens, he concentrates on huge, time-consuming civic works. His ongoing commissions include an F.D.R. monument for Washington (begun in 1972, and delayed by, among other things, reels of red tape), the Duke Ellington Memorial for the northeast entrance of Manhattan's Central Park (conceived in 1979), and a formidable Feathered Serpent for the city of San Jose. Among his completed public works are Detroit's Monument to Joe Louis (a gargantuan fist suspended inside a schematic pyramid, unveiled in 1986) and the Olympic Gateway, erected for the 1984 Games in L.A. Despite such ample subsidies as the $1 million raised privately for the Duke Ellington piece, Graham insists that he makes no money on these civic sculptures. But he has become a rich man by selling the reductions, recasts, and fragments related to the commissions.

In Graham's rambling Venice studio—where there are more odd body parts than in a mannequin factory—the sculptor expatiates on the purpose of his publicminded art. "The outdoor sculptures become living things that people really think about," Graham says. "Museums emasculate art. Busloads of people still go by the gateway and take pictures." (This may have as much to do with the titanic male and female figures' full frontal nudity as with the monument's iconic potency.) "An artist's authorship is not important," he continues. "A work takes on its own, separate life. The modernist notion of an artist making art for himself is an aberration, a blip— bullshit. . . . Picasso was a greedy, masturbatory little child." Graham says he chooses the human body as his subject because "everything is an extension of it—architecture, tools. Even the human spirit has to have the cocoon of the body—think of Jesus Christ." Behind his tortoiseshell-rimmed glasses, Graham, outwardly placid, seems constantly to be watching, alert to minutiae and generalities alike, taking in more than he will ever let out. Whatever the thoughts flickering behind those vigilant eyes, most will remain unspoken. Graham's artist friend Ed Moses says, "Bob is the last of the Mohicans. He's a contemporary shaman. He knows how to cross that boundary between magician and magic man. A magician manipulates the eye, tricks, dazzles. A magic man understands the essence of art—the transformation of the human condition.''

"Robert focuses on women rapturously as if they were pieces of culoture"

" Bob is the last of the Mohicans.He's a contemporary shaman."

Graham has undergone some major transformations himself since, as a child of mixed Scottish, English, and Incaic parentage in Mexico City, he started sculpting toys in Plasticine. His father died early, and he was brought up by what he calls "three mothers''—his real mother, his aunt, and his grandmother. His unusual childhood has all the elements of the traditional tales invented by the ancients to explain the genius of great men. It's an upbringing that also recalls the myth of Bacchus, who, abandoned by his father, Zeus, was nurtured by a group of adoring nymphs. Graham himself evokes the bewildered little boy in Fellini's 8½, who is encircled by towering women. Mystics of the Rosicrucian order, his mother and aunt relocated to San Jose when he was twelve to work at one of the occult group's headquarters. With no siblings to interfere, Graham fashioned his own little world in clay. "A lot of artists felt a solitariness growing up, or were displaced from their own country," Huston notes, comparing Graham to her father, legendary film director John Huston. (Graham's cigars also remind her of her father. "I could always tell where he'd been in a hotel by the scent of his cigar smoke," she says.) Doted on by the "three mothers," Graham says he ''was very spoiled. I was always making things simply because I was allowed. I got away with it. They never made me feel peculiar about it."

All these benevolent feminine attentions left Graham with "a passion for and awe of women. As a man I prefer the female form, so I prefer it as a sculptor. It's the most basic thing. Everything boils down to being a man or woman and how one responds to the accident of gender." His response to that accident was to evolve into not only a sculptor of meticulously observed nude females but also a womanizer. Twice married, he became notorious after his last divorce for the succession of beautiful, usually blonde conquests— some of them his models—he squired about town. "He wraps himself up in women, focuses on them rapturously, as if they were pieces of sculpture," says an observer, who describes one former girlfriend as "an amazing-looking thing in short leather—a Brigitte Nielsen type." But, says his friend artist Billy A1 Bengston, "he always has good, gentlemanly breakups." "His first wife remains one of Bob's major fans," adds Ed Moses. Graham says, "I'm bringing nothing from my other relationships to this marriage. It's going to be my last. I've had enough practice to get it right this time."

(Continued on page 274)

(Continued from page 247)

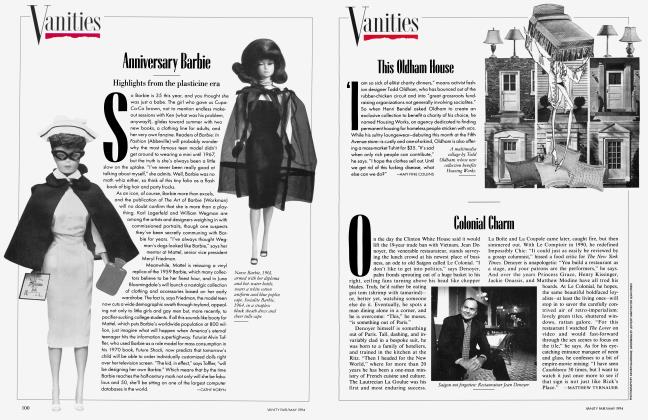

Nubile girls were the subject of his art from the start. His first L.A. show, held in 1966 at the Nicholas Wilder Gallery, featured miniature "jokey tableaux," says L.A. Times art critic William Wilson, "of beautiful nude chickies in narcissistic poses." Rendered in flesh-tinted wax and encased in Plexiglas boxes, these portable, pocket-size sex dolls were—except for their scale—so uncannily lifelike they sported tan lines and wigs made from the hair of Wilder's Afghan hound. Graham persevered with what he calls his "adolescent work" during a stint in London, but, back in California in the early seventies, he made the decision to start casting in bronze. "He told me everyone looked at his wax figures as if they were toys," Wilson says. "But bronze had been taken seriously for centuries. He hooked himself up to the great Western tradition of sculpture."

Patrons Marcia and Frederick Weisman provided him with his first commission in bronze, Dance Door, completed in 1978 (and since given to the L.A. County Music Center). Mrs. Weisman, Norton Simon's sister, adored Graham's work so much that when she died last fall she was buried with a tiny sculpture—a dramatic illustration of the fact that collectors do not part readily with Graham's work. They're more likely to donate it than sell it. "Bob's things never come up on the resale market," says dealer Robert Miller.

During the eighties, Graham unexpectedly flowered into the Bernini of L.A. Today, everywhere you turn there are fountains, gardens, columns, even a house of his design. And like the seventeenth-century virtuoso who so indelibly altered the appearance of Rome, Graham is a flourishing entrepreneur who ably manages a large workshop of about a dozen employees—including his driver, Nick. "Bob's too distracted by his own thinking to drive himself," Huston says. "Without his luxuries it would be impossible for him to do what he does. " For an artist, he sticks to a surprisingly conventional schedule, arriving most mornings at his Venice studio by nine A.M. Huston says he "wakes up champing at the bit. He can't wait to get 'to work." Graham laughs when I tell him he maintains shopkeepers' hours. "Yes, and I sell the best magical amulets around."

Nick takes me on a Graham tour of the city—a drive that amounts to a viewing of the Seven Wonders of L.A. There's Venice's Doumani House, a handsome cubic Gesamtkunstwerk orchestrated by Graham. It is home not only to Roy and Carol Doumani but also to Graham's sculptures, cabinetry by Billy A1 Bengston, furniture by Larry Bell, a stained-glass door by David Novros, and mosaics by Joanna PousetteDart. Then there's the lyrical Weisman Dance Door; the monolithic, totemic Retrospective Column in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the acrobatic fountain figures in Wells Fargo Court; the agile, Degas-esque girls of the Dance Columns in the U.C.L.A. sculpture garden. And more—the Bunker Hill Steps, where his Source Figure fountain was installed in late June. Finally, there's the heroic Olympic Gateway.

In 1989, Graham retreated from sculpture and began to draw relentlessly—an activity that recalls Michelangelo's exhortation to a young apprentice: "Draw, Antonio, draw, Antonio, draw and don't waste time!" When the sculptor finally returned to his medium, critic Wilson, dealer Miller, and L.A. County Museum senior curator Maurice Tuchman all detected a subtle but powerful change in his work. "For the first time I was utterly knocked over by its warmth, wit, and humanity," Wilson says. He cites the recent Source Figure—a spellbinding portrayal of a goddesslike black woman cupping her hands above her loins—as evidence of the artist's metamorphosis. "It's an extraordinary work of twentieth-century sculpture—destined to wind up in the history books." Back in New York, I go to see a cast of the Source Figure, displayed in the dining room of Robert Miller's Upper East Side maisonette. Remarkably, the statue holds its own among the dealer's impressive sculpture collection, which includes Roman heads of Apollo and Tiberius, Rodin's Age of Bronze, and a colossal Canova bust of Napoleon. Less than a week later, Miller informs me that a midwestem collector has purchased the Source Figure right out of the dealer's dining room, for around $200,000.

Graham's character, along with his art, has undergone an evolution lately. "He's become a Renaissance man, capable of doing anything," Wilson says. "Sculpture, drawing, photography, architecture. For the F.D.R. monument he's taught himself to do bas-reliefs. He used to be a cool, monosyllabic Venice artist. Now he's courteous, and capable of the most erudite conversation. He couldn't have done that five or ten years ago. People are saying, 'What is this marvelous thing that has happened to Bob? It must be Anjelica.' I don't know if the relationship uncorked the whole thing or the other way around. But it certainly embodies the new Bob Graham." Over cocktails in the statue-dotted, functional living room of his Venice house—a former bank building—Graham allows, "I'm in a good place emotionally now. I have comfort, support."

The relationship also seems to have enabled Huston to come into her own. "The big difference between Bob and Jack Nicholson is. . .everything," says Billy A1 Bengston. "They're both tough taskmasters, but Bob is much, much more supportive." As if her acting career were not enough to satisfy her, Huston has suddenly emerged as a political force as well. Two and a half weeks before her wedding, while George Bush is in town, Huston is on the podium addressing a "Heal L.A." rally, and helping to lead a peaceful protest march from Century City to Beverly Hills. "She's never gotten politically involved in this way before," says Huston's best friend, writer Joan Juliet Buck. "It comes from a kind of confidence you only get when you feel complete." Her auburn hair and lushly fringed eyes shining, Huston echoes both her fiance's and her friend's words. "We have a connection. He gives me comfort, support. It's a very basic thing, but very difficult to find. It makes it easier to go about the rest of your life and work." Her calm radiance, which seems to glow throughout the Beverly Hills Hotel's Polo Lounge, stands in distinct contrast to the forced hilarity at a nearby table. It makes her wince, but she keeps her composure.

The mastermind, or "fairy godmother," to use Huston's words, behind the match was record executive turned art dealer Earl McGrath, famous for his starpacked gallery openings; he was also best man at the wedding. "It was gay-parade weekend two years ago," Huston reminisces. "Earl asked Bob to pick me up to take me to his house for dinner, because he knew it would be hard to park the car. After dinner we went up to Earl's roof to watch fireworks." McGrath says, "He had been going out with a lot of young girls who weren't right for him. One girlfriend, beautiful and blonde in a boring way, had 'done him wrong'—she ran off with Ed Moses's son. When he told me, I said, 'Get someone closer to your own age. ' I gave him a big talk about Anjelica. I told him, 'She's smart, funny, interesting. She has a career of her own; she's mature. ' I knew it would take off. Even physically it seemed right. They're both tall and dark. They look good together. Now he's more focused on his work. Before, he was distracted, always making plans to go out."

Huston adds, "When we first met, we had a tremendous amount to say to one another. We talked so intensely, so passionately, waiters wouldn't come near us. We both had been smarting from previous painful relationships. We unloaded a lot of garbage on the floor." Graham says, "I was attracted to her immediately." A year and a half later, they became engaged in Ireland. He gave her two silverand-lapis ceremonial daggers (he's an expert knife thrower), a "ceremonial ring," and "a real ring to wear"—a Brazilian sapphire set in gold—all designed by a German jeweler friend. Even though, according to Buck, as a little girl her friend used to play constantly at being a bride, as an adult, Huston says "the subject of marriage had always given me a sense of panic. But I've not had any doubts about marrying Bob. I trust him. I feel protected when I'm with him. He has beautiful manners. Even after two years he still lights my cigarette and pulls out my chair. He's courtly, serene—but with a trace of Mexican wildness."

This trait set the tone of the wedding celebration, held in a tent pitched on the site of Graham's new studio. A'salsa band played all night, while Brazilian dancers in mirrored bikinis and a skinny androgyne in a grass skirt performed for about four hundred guests. The party spilled over to the restaurant across the yard, 72 Market Street, where three more bands— including the all-girl Blue Bonnets— played. The wedding ceremony, which had taken place earlier that day at the BelAir hotel, was a more subdued affair. It was so private not one paparazzo showed up. The wedding party, which included, among others, Billy A1 Bengston, Ed Moses, and Graham's son, Steven, as ushers, and Jerry Hall, Michelle Philips, and Sabrina Guinness as bridesmaids, was "almost bigger than the congregation," said Joan Juliet Buck, the maid of honor. Huston, wearing what Buck described as "a blinding-white dress—the whitest thing anyone had ever seen," was given away by her brother Tony.

Huston and Graham's mutual respect is founded partly on the awe they feel for each other's work. "After watching Anjelica act, I'll ask her, 'How did you do that?' " Graham says, beaming. "And she'll reply, 'Do what?' " Huston admires Graham's "tremendous concentration and extraordinary powers of observation," but she has never watched him work. "He's very private about it. I wouldn't dream of it. It would be like walking onto someone else's film set." Nor has she, a consummately statuesque woman, ever modeled for him. "He's never asked me. It's a long, arduous process. His models faint, I hear." Graham, who customarily works for years on a single sculpture, simply says, "I haven't known her long enough for her to be a model. ' ' He is, however, putting together an album of photos of Huston, taken from a video he made of her—in effect, two-dimensional color versions of the single-figure bas-reliefs he's currently experimenting with. And clustering around the base of the column supporting his Source Figure are several bronze crabs—symbols of the sea and of life's origins, but also Huston's astrological sign.

Buck, who threw an engagement party for the couple last year, recounts, "It was totally obvious from the way Anjelica first spoke about Bob that he was not just someone in her life. He was it. Anjelica introduced Kathleen Tynan and me (we're both single) to Bob when we were all in Italy in September 1990. Afterward, Kathleen said to me, 'My God, she looks so beautiful.' And I agreed: 'Yes, she looks so happy.' And Kathleen added, 'But not in that tense, brittle way when it's simply a hot affair.' And we exclaimed, in unison, 'No, it's True Love!' And then we both burst into tears!"

Buck pauses and reflects. "Bob's got that dancing elegance. Even in his tiniest figures you see the essence of some lost perfection. But thanks to him, it's not lost. Because he's doing it right here, right now."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now