Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

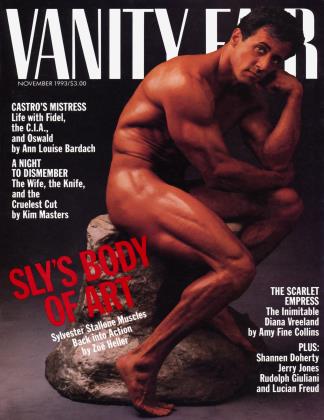

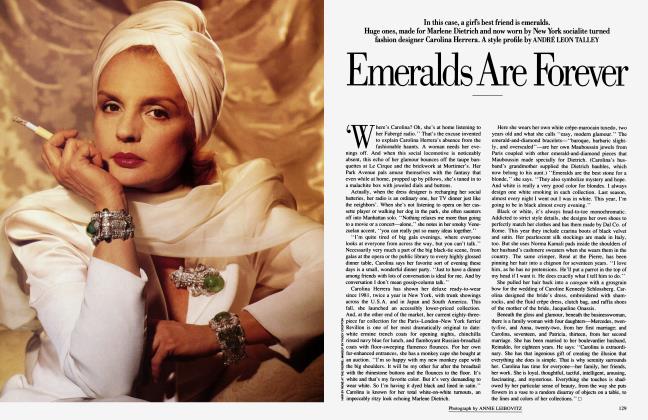

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAt 47, Sylvester Stallone is flexing his muscles on all fronts: his body is bulging, his spirit is soaring, and, thanks to Cliffhanger, his career is back on track. At home and on the set of his next action pic, Demolition Man, ZOË HELLER pumps Über-male Sly for his thoughts on girlfriends and aging gracefully, male bonds and biceps curls

November 1993 Zoë HellerAt 47, Sylvester Stallone is flexing his muscles on all fronts: his body is bulging, his spirit is soaring, and, thanks to Cliffhanger, his career is back on track. At home and on the set of his next action pic, Demolition Man, ZOË HELLER pumps Über-male Sly for his thoughts on girlfriends and aging gracefully, male bonds and biceps curls

November 1993 Zoë Heller'So, can I feel them?" I asked. "Your muscles?" Sylvester Stallone paused a moment, then his little rosebud of a mouth puckered and he let out one of his gurgling, childlike laughs. "Sure," he said. He was lying aloft one of the giant, shiplike sofas in his Benedict Canyon mansion. Behind him, in the hallway, stood Rodin's Eve. Over by the bookshelves, where leatherbound Franklin Library editions of Thoreau and Melville sat side by side with In the Arena, by Richard Nixon, and Mr. T by Mr. T, a stuffed lioness was posed in silent roar. ("Oh that," Stallone groaned. "My brother, Frank, brings back all these stuffed animals from Africa and I got to keep 'em in my house.") In the far comer of the room, there was a custom-made bar with stools and doilies, but our drinks were brought in from the kitchen by Stallone's Liverpudlian personal assistant, Kevin.

Stallone had arranged himself in supine splendor—arms forming a cradle for his head, head crowned with a sun visor. His legs were splayed akimbo, advertising the hair-raising brevity of his cotton shorts. Even in repose, his hulking limbs bring to mind the steaming sides of ham that Dickens always writes about when describing feasts of celebration. One thigh alone could feed Bob Cratchit's family for a year.

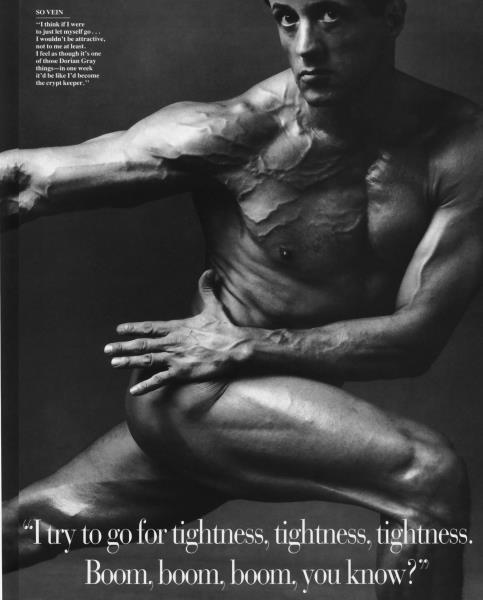

He leaned forward now, allowing me to prod tentatively at his triceps. "This is interesting," he said. "Look at this one here." He pointed at a pulsing, three-dimensional vein running the length of his right arm like a violet-colored snake. "Oooh," I said. He smiled, pleased. "Isn't that weird? I started to get it in Rambo, and then in Cliffhanger it really came up big. Matter of fact, look at this." He raised his forearm—the size and shape of a bowling pin—and began to tense it, causing it to expand and all its sinews to bulge. "If that gets any bigger," I said, "it'll explode."

"Right," he said. "I'm 47 years old. It can't get bigger. In fact, I'm trying to lose some weight now because I saw some pictures of me recently and my arms—I swear to you—had to be this big," he gestured in the manner of a boastful fisherman. "I thought, My God, people are going to be looking at me, saying, 'Did he have a breast implant put in his biceps—I mean, is that a double-D arm or what?' I'd rather be hard and smaller. You know, Arnold [Schwarzenegger] has kind of that big thing. I try to be a little lighter, because I have small bones. I was getting muscles in my eyebrows. My teeth were getting muscles."

"I try to go for tightness, tightness, tightness. Boom, boom, boom, you know?"

He pointed at his left leg and began twitching his calf muscle up and down. It looked as if a small rodent had burrowed beneath his skin and was now performing tricks. "It's not so big," he said modestly, "but I try to go for tightness." He stared down at the leg for a moment, his great, melancholy bruise of a face dark with concentration. "Just tightness, tightness, tightness," he muttered in a sort of reverie. "Boom, boom, boom, you know?"

It's been a while now since Stallone was prepared to wax this enthusiastic over his physical assets. In the 80s, fed up with being taken for a real-life composite of Rocky and Rambo (Rockbo? Ramby?), he set out to prove he could do things aside from punch and shoot and sweat prodigiously. He was determined, he said, not to end up "like James Brown—still doing the splits at 60." So he acquired suspenders and triple-pleated pants. He developed a need for brainy-looking eyeglasses. He gave up action movies in favor of lighter, brighter roles in comedies. He put on exhibitions of his oil paintings and professed a long-standing ambition to make a film about Edgar Allan Poe. As for the muscles, they went into hibernation, lurking furtively beneath layers of snazzy pinstripe.

It was a valiant escape bid, but Stallone didn't make it past the first line of jailers. The comedies—Rhinestone, Oscar, and Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot—all flopped. Critics sneered at his pretensions. And no matter how he dressed, how many paintings he sold, or how many times he was quoted referring to Ionesco, fans never stopped chanting "Rocky! Rocky!" when he turned up at premieres. Earlier this year, he bit the bullet and unwrapped the beefcake again for the action adventure Cliffhanger. "Sly wanted the big comeback," the film's director, Renny Harlin, says. "He wanted to say to the audience, 'O.K., here's the Stallone you learned to love in Rocky.' "

When Cliffhanger proved a box-office success, Stallone decided he was being given a message too loud to ignore. Branching out hadn't worked for him. Action pictures were where he belonged. So, now the muscles are back.

"I was being wrapped up in old newspapers. I coulda walked round here on flame and nobody woulda put a marshmallow on my body. It was pretty dismal. I was like 'Maybe I could become a guide somewhere in South Africa, or a hunter.' " He shakes his head. "Jesus, it was bad.

"When Cliffhanger came out, the people who write the articles started venting what they had really been thinking about me," he says. "It was like 'Stallone back from the grave, after a totally dismal five years.' I'm reading this and I'm like, God! If I'd known it was like that, I woulda killed myself! Jesus! It woulda been a situation like 'Take all sharp objects out of the room. ' I woulda plunged a dagger in my heart!"

The relief of having made the comeback is intense. Stallone is still bugged that the public won't accept him in comic roles. "I tend to look at life in a kind of comedic, satirical way," he says, "and yet I'm perceived as a man who's deadly serious and nonsensical, and that's not really it at all." He is still touchy on the matter of his intellect—still eager to impress with fancy words and literary namedrops and accounts of his poetry writing. "It's not iambic pentameters or anything," he says of his poetic efforts. "It's blank verse—I've gone from the e. e. cummings mode to the Tom Waits-school-of-poetry mode. I wrote one the other day. I write this poem and then Kevin thinks I stole it from a book. I said, 'Yeah? Then why is it written on the back of a hatbox, O.K.?' "

But if he hasn't come to terms with his public, lunkhead persona, he has at least given up struggling against it. "I'm resigned now," he says, making a resigned face, "to doing things that I think befit the image and not trying to break type as blatantly as I have before." In his new, pragmatic mood, Stallone is even prepared to acknowledge that the Edgar Allan Poe project will probably never happen. "Sometimes," he says with a sigh, "my aspirations far exceed my abilities. I would like to do Edgar Allan Poe, but I bring so much handmade baggage that there's no way you could ever accept me as a frail, withdrawn poet who basically approached life on the intellectual level. The audience just wouldn't buy it. They'd expect me to be like 'Yo, Poe!' "

The day after the muscle-feeling session in Benedict Canyon, I go to visit Stallone on the Warner Bros, lot, where his next movie, Demolition Man, is being filmed. When I arrive, Stallone is standing around on a shiny-floored high-tech set, waiting to be abducted by a giant mechanical claw. Demolition Man, to be released in October, is a futuristic action thriller directed by Marco Brambilla. Stallone plays a brutal L. A.P.D. sergeant who pursues a psychopathic criminal (Wesley Snipes) through time, into the Los Angeles of the year 2023. The scene they are working on this morning is a shoot-out between Stallone and Snipes in a "CryoPenitentiary"—the cryogenic rehabilitation center in which both have been frozen for 70 years. When Stallone starts racing across the shiny floor, banging his gun, the claw is supposed to descend, pick him up, and carry him away while he mimes suitably manly anguish. Unfortunately, the claw machinery is acting up.

"I say, 'Look, if you're gonna go cheat, at least come back and have learned something new. At least come back with a new trick!' "

As the grips and special-effects advisers busy themselves with fixing it, Stallone tries to keep himself and the rest of the crew amused. He wanders about with that odd tough-guy gait that makes him look as if he were carrying invisible packages under his arms—jovially biffing cameramen in the ribs, pretending to stab his makeup man in the neck, shadowboxing with his golf coach. Stallone is very fond of this boysy play punching. "I like the one-upmanship, the constant hands-on, the shoving," he says.

Stallone is swigging root beer, singing Ray Charles's "What'd I Say?" into a Q-tip, and practicing his gun draw when he notices me standing in a comer. He comes over with a clamp device that he's borrowed from one of the grips and snaps it menacingly in the direction of my stomach. "This is the diet meter," he says. "Aw, c'mon—everyone has to pass this test." When I politely demur, he moves his attention to two rather tubby grips. There is much raucous laughter as he tweaks at their bellies with the clamp. "A lot of testosterone on this set," one of the crew murmurs to me, a little wearily.

Joel Silver, who is producing the movie, keeps bustling in and out of the soundstage in a voluminous pajama suit and a cloud of Paco Rabanne. He agrees about the testosterone. "Sly is not a stay-in-the-trailer kind of a guy," he says approvingly. "He's not the kind who disappears and only comes out when he's needed. Movies like this are skewed towards the young male, so they have that macho, bonding thing about them on the set. You have the stunt guys and, you know, the prop guys and the gun guys and—maybe it's childish, maybe it's immature, but the youngmale aesthetic really seems to filter down into the production."

The claw is finally working again, and Stallone limbers up for the next take by doing thigh lunges and yelling "Motherfucker!" Then it's action. White smoke begins to billow across the set as Stallone starts shooting. The claw comes down and hoists him up. He struggles. Cut. The claw has malfunctioned again and Stallone has hurt his hand. Then one of the steam canisters appears to explode. A grip limps off the set. "And they dismiss action films as easy!" Stallone says, rolling his eyes.

Stallone is committed to making action pictures for the next two years at least, and naturally he is a little defensive about the genre. Doing action doesn't condemn him to an endless repetition of the same bang-bang formula, he says. All of his upcoming movies have something exciting and unusual about them. Demolition Man is "kind of unique" because "it attacks a well-known theme from a new angle which is kind of social commentary/funny. . . . And then again," he adds, "it also has a lot of action." His next film, Fair Game, is ' 'kind of unique' ' too, in that it will be an erotic action thriller. In it he will get to ' 'make love, have a real hot thing, and also be emotional." He can't wait.

"I wouldn't want some wimp," Flavin says, "who wants to hang out and bake bread."

"I'm dying to do this for once," he says. "I mean, my God, I figure it's something I know a little bit about and yet I've always been guided away from that. . . . When the results of Cliffhanger came out and 40 percent of the audience were females, I realized I'd been doing myself a disservice by not really getting involved in the feminine mystique fullheartedly."

Besides Fair Game, there'll be another futuristic action thriller: Judge Dredd, a movie based on the cult comic-book series of the same name. This will offer the "ultimate" in special effects. "There's usually a very negative connotation to action films," Stallone reflects, "like they're the lowest form on the food chain. But they are really the mother ship of films. Very special films don't happen very frequently. So I want to take the opportunity to do these incredibly unique things now, while I'm physically able to." Stallone, one can't help noticing, has a very keen sense that his time is running out. "I keep thinking I'm 14 years old," he says, "and I realize, No, you are actually past midlife. They say 'middle-aged,' but how many guys do you know who live to 90? I'm beyond middle age." His official line is that he feels "exuberant," that his body is still "blossoming." But beyond these cheery prognostications, there lurks a more fretful response to the aging process. In Stallone's garage at home and in a specially designated area on the set, a vast array of gleaming white weight machines have been set up for his use. He works out twice, sometimes three times, a day—a routine he dislikes but regards as essential. "I have to work at it," he says. "I think if I were to just let myself go—eat what I want and stay out as much as I want and drink what I want—I dunno, I wouldn't be attractive, not to me I wouldn't be. I feel as though it's one of those Dorian Gray things—in one week it'd be like I'd become the crypt keeper. I see it when I go to New York. I'm there for about four days and I get up and look in the mirror and I realize what I'm going to look like at 60 ... I just start to self-immolate, I become decrepit."

SO VEIN "I think if I were to just let myself go... I wouldn't be attractive, not to me at least. I feel as though it's one of those Dorian Gray things—in one week it'd be like I'd become the crypt keeper."

SO VEIN "I think if I were to just let myself go... I wouldn't be attractive, not to me at least. I feel as though it's one of those Dorian Gray things—in one week it'd be like I'd become the crypt keeper."

The regimen required to keep a 47-year-old action man looking his best is not only strenuous but for the most part fantastically dull. Stallone sticks religiously to a high-protein, low-fat diet, and when he's working he eats exactly the same thing every day—in accordance with the dubious theory that a monotonous eating program is healthier than a varied one. Why, one wonders, does he bother? He has enjoyed great commercial success with action films for 17 years. He is an extremely rich man, with an enormous new house in Florida. Why doesn't he say to hell with high protein and early-morning workouts and opt for a splendid retirement, playing golf and eating chocolate cake?

"I don't know," Stallone says. "I don't know if it's because of a tremendous insecurity or a vacuum that's unfathomable, that I can never fill—a void in my childhood—but there's a sense that I'm incomplete. It just takes a continual challenge to validate my ... I could never just walk away and say, 'O.K., I did it all, I'm done'... I believe the world is real rough. Real rough. It's kind of a barroom brawl. You just try to survive it and the only way I survive it is by constant challenges."

On Stallone's living-room wall in Benedict Canyon hangs one of his paintings—a large, luridly colored canvas depicting an old man riding piggyback on a young woman. Stallone calls this painting Errol at Ten—a reference to Errol Flynn. "It's about symbols who were basically demigods in our industry," Stallone explains, "how frail they were when they were offscreen—the insecurities and maladies they had. ... As men get older, they try to grasp on to something that will retain their exuberance and youthful attitude. So I use the image of him riding piggyback on this young waif's back, trying to carry him back into the past, when he was younger."

As always, Stallone says, he has used color to convey "the psychological aspect" in this painting. "Colors," he says with a lush giggle, "are almost the way you'd have a psychological Pap smear— you know what I mean?' ' He points to the man in the picture. "You can see I've given him a red hand, because he knows he's going to hell for what he's doing. . . . The green there is representing all the wealth. And the blue, the depths of despair. And I've got a clock over there in the righthand comer. It represents his life. He's heading towards the midnight hour, so he's just about had it."

"Is it autobiographical in any way?" I ask, assuming that this is what Stallone has been broadly hinting.

But he looks taken aback. "Ha, well," he says. "Not overtly, you know. But, well, I'm sure something dwells in there." He thinks for a moment. "It must have come from me," he says, "kind of percolated from me—somewhere."

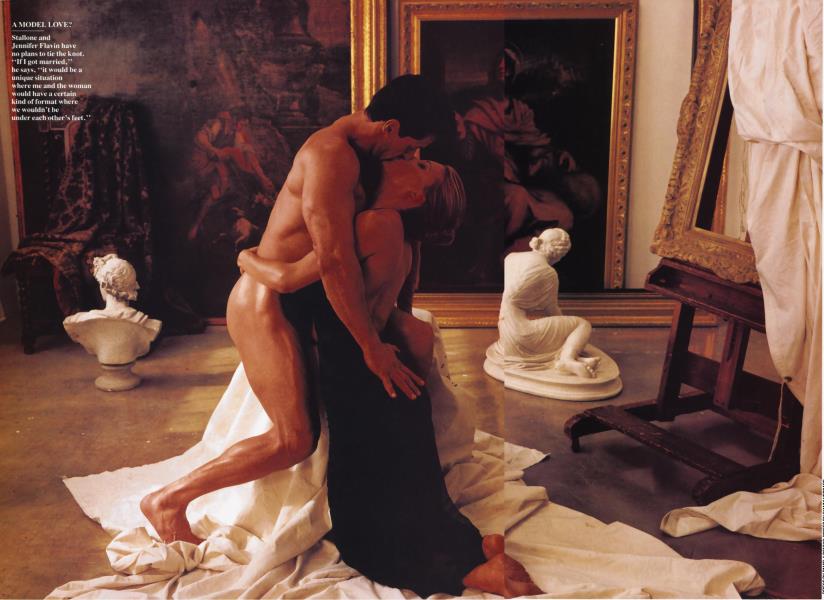

Whether or not she could aptly be described as "a waif," Stallone does have a much younger woman in his life. The 25year-old model Jennifer Flavin, who has been his girlfriend for the last 5 years. She appeared on the Demolition Man set the day I was there—a honey-brown vision in suede mules, Levi's, and short, midriffbaring T-shirt. Stallone was in his trailer at the time, wearing only an extremely scanty pair of underpants, having a stunt harness fitted. The news that Jennifer had arrived prompted much ribald joshing between him and his trailer cohorts. "Where's the music?" he said as he put his clothes back on. "I need music when I make a full-frontal assault." Outside, he greeted Jennifer with a few playful biffs and then they shyly embraced. A gaggle of guys who had been waiting all morning to banter with Stallone about boxing and golf stood around to watch this highschool tableau—the class stud meeting his prom queen.

Flavin is a proper dream of girlie perfection. She talks in a soothing whisper and laughs a tinkly, demure laugh. Up close, she smells girlie, too—a sort of dewy, fresh-out-of-the-bath smell. From time to time, a wisp of her shiny hair will fall into her eyes and she'll pluck it away with a delicate gesture of her pinkie finger. To see her and Stallone together is to glimpse a world in which gender stereotypes are lived truths.

'Love makes you dumb! It takes intelligent persons and makes them walk around with their thumb in their mouth, becoming human drool cups."

"I just watch and I listen and he fascinates me," she told me when we had gone to the soundstage to watch Stallone do some more grappling with the giant claw. "He just intrigues me by what he does and says. He may talk a certain way to you or to someone on the street, but when we get home, the way he speaks to me— so eloquently. . . . And he writes poetry and he paints and he can direct and he can act and he can. . . everything. There are just so many things about him."

Given this level of unchecked admiration, it's not hard to believe that Flavin and Stallone rarely argue. The most serious contretemps that Flavin has ever acknowledged was a tempestuous little spat over Gummy Bears. "One time, I was eating Gummy Bears," she told a reporter, "and he came back in a grumpy mood. He had told me not to eat candy, and he started screaming at me for eating them. Then he broke a plate and threw the Gummy Bears at me."

What rows there are, Stallone takes the blame for provoking. But generally speaking, theirs is a very placid relationship, Stallone says. "I incite her purposefully because I think it's good every now and then to, like, purge oneself of all the angst."

"He's a Cancer," Flavin says. "He's very sensitive. He's very generous. He gives me so much of himself. I mean, on weekends, he could be out hanging with his friends—well, he does go and play golf on the weekends—but most of his time off he spends with me. And that's more valuable than anything he can give me."

Stallone is a man's man, she says. "I let him be that because I wouldn't want him any other way. I wouldn't want to be dating some wimp—some guy who wants to hang out with me on the weekends and bake bread. I like that he wants to hang out with the guys on Friday nights and that he likes to play golf on Saturdays and Sundays. That's O.K. I understand it."

In spite of all this rampant harmoniousness, Stallone and Flavin have no plans to marry in the near future. "If I got married," Stallone says, "it would be a unique situation where me and the woman would have a certain kind of format where we wouldn't be under each other's feet and the mystery must be maintained. I impose separation. I insist on people blatantly pursuing other jobs, travels, sports, whatever. ''

And other love affairs? When I ask Stallone whether he is good at monogamy, he laughs. "Monopoly, did you say?" Pressed further, he adds, "Like all good things, [monogamy] takes practice. It's an unnatural state for an incredibly long duration. But it's certainly attainable."

"So your understanding with Jennifer doesn't stretch to seeing other people?"

"No, no way. That would be catastrophic. I've been actually ... a pretty good guy."

And if Jennifer ever ended up cheating on him, Stallone says he would accept it, knowing that all is fair in love and war. "I believe that if someone's going to cheat, there's nothing you can do about it, and constant monitoring only aggravates the situation." We are back at the Benedict Canyon mansion, and Stallone has stood up now to amble about the living room. "So I say," he continues, " 'Look, if you're gonna go cheat, at least come back and have learned something new. At least come back with a new trick!' "

He has learned this realism after many years of being burned. "I've been scorched! I used to have a condo on Mount Vesuvius, before it blew up." The biggest bum of all was, of course, his marriage to Brigitte Nielsen, a short-lived and unhappy business that broke up in 1987. The trajectory of their romance was spectacular, but brief. Now Stallone warns with an almost missionary zeal against the dangers of torrid love.

"Hot affairs are dangerous," he lectures me. "You gotta understand you're going to get scorched. There's no doubt about it—love under those circumstances makes one incredibly stupid. Now, you're saying, 'What do you mean? That love is dumb?' Let me just explain because this is important, LOVE MAKES YOU DO STUPID THINGS! IT MAKES YOU DUMB! It takes intelligent persons and makes them walk around with their thumb in their mouth, becoming human drool cups. IT MAKES THEM STAGGER THROUGH THE NIGHT, LOST! It takes people who run entire NATIONS and turns them into babbling idiots, YES! LOVE MAKES YOU DUMB!"

After he finishes, there is a long pause. "So," I venture finally, "with Jennifer, you've opted for something a little calmer. Is that it?"

"Yeah, a little calmer," Stallone says quietly, coming back to sit on the sofa. "I've been through the hot and I'm covered with bums. I can't deal with it."

Tony Munafo, who started out as Stallone's bodyguard 16 years ago, is now Sly's associate producer and the man Stallone calls his "best friend." He says that Stallone's experiences with Nielsen have frightened him. "Sly's afraid to get married now," he says in a New Jersey accent you could slice with a knife. "I begged him not to marry Gitte. I knew she was going to be bad for him. I got bad vibes about her from the beginning. She hated me. I always treated Gitte very nice, but she knew I didn't trust her. I was on my knees in the Rolls-Royce on the way to the wedding—begging him, 'Don't do this!' But when you're in love, you're in love. Sly really loved that woman."

If Stallone has learned to be wary of hot romance, he remains very keen on hanging with the guys. And it is men who inspire his most sentimental eulogies. "You wanna know about me?" he says. "Meet Tony Munafo. We've fought together, we've had fistfights together. He's been there since the beginning."

As for Munafo, "Anybody ever hurts Sly," he says, "I'll kill 'em. The love is too strong. I will never leave Sly. Hear what I'm saying: I will not leave him till death us do part. It's love between a man and a man."

A MODEL LOVE? Stallone and Jennifer Flavin have no plans to tie the knot. "If I got married," he says. "it would be a unique situation where me and the woman would have a certain kind of format where we wouldn't be under each other's feet."

A MODEL LOVE? Stallone and Jennifer Flavin have no plans to tie the knot. "If I got married," he says. "it would be a unique situation where me and the woman would have a certain kind of format where we wouldn't be under each other's feet."

When I ask Stallone if he prefers the company of men to that of women, he smiles. "I've always thought about this. If I was stuck on an island for 20 years, who would I rather go with? My best male buddy or the most beautiful woman in the world? I'd definitely go with my buddy. You could have wonderful sex with a girl. You could run on the beach, watch perfect sunsets. The wind would cascade through her hair, there'd be a flower behind her ear . . . Cut to 10 years later: O.K., enough already! I mean, what do we talk about? It'd be a whole different thing. So I would think that the outrageous, raucous, stupid banter guys often enter into would be preferable to the politically correct relationship between a man and a woman for 25 years."

Generally speaking, Stallone is not keen on political correctness. "I'm a little put out by it," he says, "because no one can say what they feel anymore. I say, let's clarify our true feelings and just say what people want to say. But you're so sensitive now to every kind of group and there's so many groups now—we're so fractionated—it's like one big congregation of antagonistic social clubs." In the past, Stallone has objected to being identified as a right-wing movie star, and he got steamed when the character of Rambo was co-opted by Ronald Reagan as a symbol of the gungho Republican spirit. But there's little doubt that his views tend toward the Genghis Khan end of the political spectrum.

"You want to get rid of crime?" he demands rhetorically at one point in our conversation. "It's so simple! But it's not going to be a pretty sight. People don't respond to idle threats. For me, if you commit a heinous frigging crime and you're caught, there is no appeal, there is no life sentence—sitting there for 30 years being a burden on our society. You have to be the receptacle for what you have sown. You have a man like the president go on TV and say, 'Look, the next son of a bitch who uses a gun in a fucking crime, I swear to you, on my family, you are going away—not to prison. You are dead. It's over. You're going to be hung, inoculated, whatever it is.' Now you have a lot of people thinking, Oh, this is a threat with real intent. Before, they're going, 'Oh, yeah, right, war on crime.' Please! Street crime you got to deal with with a street mentality."

Outbursts like these will doubtless ensure that the public continues to blur the distinction between Stallone and the toughies he plays on-screen. But if Stallone knows this, he doesn't care—at least not anymore. His tendency to speak without calculation or self-censorship is one of the things he likes about himself. It is a sort of "immaturity," he admits, but he is pleased to have some connection with his younger, neophyte self—the self that existed before stardom and savvy set in. In his acting and in his life, he is constantly striving to keep in touch with the unlessoned innocence of his youth.

"It's kinda like, you know, the first time you really leam to conduct yourself in a love affair," he says. "You're kinda stupid, unmannered, raw. You don't have a style yet, you're not cool. You don't know how to seduce yet. [Later on] you discover that to really win a woman over you gotta find where you can talk to that childlike innocence, that thing in there that makes a woman, like, abandon all her inhibitions—and you too—where you feel absolutely childlike. . . . For most people in my experience, the lovemaking aspect becomes a sort of 'Hello, how are you? Here's a drink, da-dee-da-da. . . ' You know: You do this, you do that, and then kepow. And that gets to be mechanical. That's not really special. It took me many years to find out the real joy is probing the unknown—getting back to naivete, getting back to the place where you feel so safe, so innocent, so juvenile, and not this guarded 'I have to be so sexy' thing."

He shifts on the giant sofa and sucks on his cigar. Beneath the sun visor, his orange-tanned face is brooding and sad. He looks just like Ferdinand the Bull. "It's the same thing with acting," he goes on. "When I was doing Rocky, I didn't know what my best side was. I didn't know about lighting, about makeup. And those were the best, the most visceral performances." He pauses.

"But is it really possible to get back to that, to regain your past in that way?" I ask.

He shakes his head. "Not easily. It's very hard. Very hard. It's like they say, once you've driven in a Rolls-Royce it's real hard to get back in the oxcart, you know?" He smiles and sips at his iced coffee. A little later on, he remembers a line he wrote back in 1975 for the first Rocky. "I coined the phrase 'Every day I try to forget something new,' " he says. "You know? Like, let's just make it a clean slate." He sighs a great gale of a sigh. "I wish," he says, gazing about him at the stuffed lioness and the drinks bar and the painting called Errol at Ten, "I wish I didn't know as much as I do."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now