Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

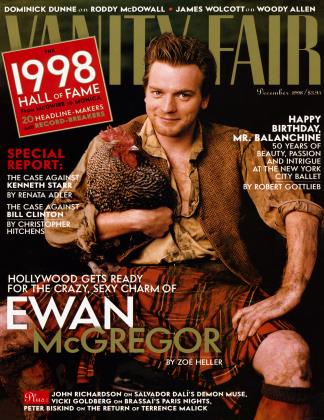

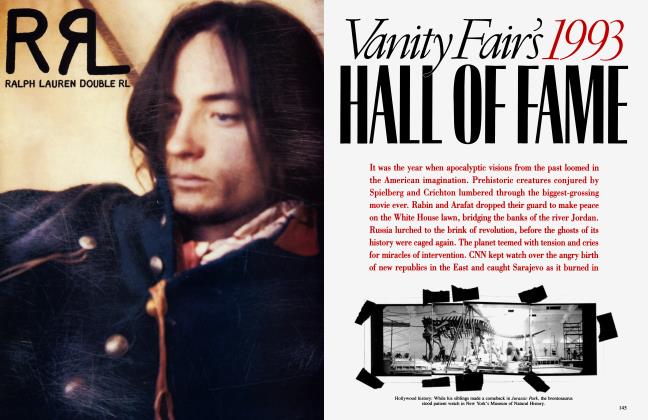

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAfter 10 movies, including Trainspotting and this month's Velvet Goldmine, Ewan McGregor looks like the biggest actor to come out of Scotland since Sean Connery. In the comically unshowbiz surroundings of McGregor's cramped London home and grimy local pub, ZOË HELLER gets an earful about how the 27-year-old star reconciles his disdain for Hollywood with his next role, in George Lucas's raptly awaited Star Wars prequel

December 1998 Zoë Heller Annie Leibovitz Bill MullenAfter 10 movies, including Trainspotting and this month's Velvet Goldmine, Ewan McGregor looks like the biggest actor to come out of Scotland since Sean Connery. In the comically unshowbiz surroundings of McGregor's cramped London home and grimy local pub, ZOË HELLER gets an earful about how the 27-year-old star reconciles his disdain for Hollywood with his next role, in George Lucas's raptly awaited Star Wars prequel

December 1998 Zoë Heller Annie Leibovitz Bill MullenTonight, in Ewan McGregor's local pub—a down-at-the-heels establishment in Belsize Park, north London—a crowd of roaring men has taken over the bar to watch a soccer game on television. Finding his usual spot usurped, McGregor has retired to a corner table with a couple of his friends, where he is now making swift work of his fifth pint of the day and bemoaning the revolting state of the pub's lavatories. "Jesus!" he exclaims in his slightly Londonized Scottish burr. "You'd think they could afford to shell out 20 quid to clean it up a bit in there. Get a lavatory seat or something! I mean ... give me 20 quid and I'll clean it up."

Notes are duly compared on the hygiene deficiencies of the men's room. "Yeah," someone says, "people throw coins into the urinal. It's like the frigging Trevi Fountain."

"And imagine," McGregor says, warming to his gruesome theme, "imagine being the guy who has the job of clearing the coins out? Eeeeuw!"

The conversation moves on. One of McGregor's friends describes falling down the stairs the other night, after a particularly hard drinking bout. "Yeah, I damaged me coccyx," he says. "And that was the end of the tale. Ha! Me coccyx. End of the tale." McGregor bangs the table and lets out a great howl of mirth, whereupon the pub landlord, a rather sour-faced Irishman, approaches. "Oy," he shouts at McGregor. "Keep it down." McGregor nods mildly and returns to his pint.

Ladies and gentlemen, meet the Great White Hope of British film. He may look like the sort of shiftless youth you see lolling around the escalators in shopping malls, but this 27-year-old—with a vaguely 70s shag and a cigarette dangling from his lips—is being hailed as the biggest thing to come out of Scotland since Sean Connery. "When I first started thinking about my movie, he was the one actor I knew I wanted to use from the start. There's no one else with Ewan's sort of intensity around," says Todd Haynes, the director of McGregor's latest, Velvet Goldmine. "Ewan has an incredible, raw power onscreen that I don't think you find among American actors of his generation."

Like many people, Haynes was introduced to McGregor by the 1996 movie Trainspotting, an adaptation of Irvine Welsh's novel about Scottish heroin addicts, directed by British director Danny Boyle. As the wild-eyed junkie, McGregor gave an astonishing performance—a speedball of scruffy sexual charm and manic energy that managed to inject the weary concept of "the lovable rogue" with a peculiarly 90s vigor. "Every now and then," says Boyle, "you come across someone who's a sort of spokesperson for a particular era, someone who sums up a particular feeling or mood. Well, Ewan is one of those people. He is such a contrast to the kind of naked ambition and hardness of the 80s. He is perfect for this time."

"You know how swimming naked is such a lovely feeling? Well, being naked on set is kind of a bit like that."

Trainspotting, which became something of a cult phenomenon in Britain, not only earned McGregor hero status among British and American twenty-somethings; it also made casting directors around the world take note. And phone Hollywood. This spring, McGregor stars as the young Obi-Wan Kenobi in the first episode of George Lucas's long-awaited Star Wars prequel—a role that is rather more wholesome, and a great deal more lucrative, than those to which he has been hitherto accustomed. His British agent, Lindy King, sums up the financial leapfrog thus: "For Trainspotting Ewan got next to nothing. For Velvet Goldmine he got 10 times that. And for Star Wars—well, he'll get 10 times that again."

For now, however, the actor's life remains so absent of showbiz perks as to be almost comical. The fourth lead on a WB sitcom has a ritzier time of it than McGregor. At his gloomy basement apartment, around the corner from the pub, the telephone has just been cut off. (His wife forgot to pay the bill.) Ragged cardboard boxes overflow with knickknacks and books that the cluttered rooms cannot otherwise accommodate. (Several more boxes are being stored down the road in the cellar of the obliging local deli owner.) McGregor has bought a house in a more salubrious area of north London, but he has been waiting more than a year for it to be renovated. "I don't seem to be able to get anyone in to move bricks," he says in an exasperated tone. "It's driving me fucking mad." Earlier in the day, when I went to his apartment to pick him up, he was crouching in the narrow hallway, fielding the calls that had started coming in on the fax-machine phone—occasionally squishing himself against the wall to allow his two-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Clara, to get by to the kitchen. In the living room, McGregor's wife, Eve, a tiny waif of a Frenchwoman in jeans and running shoes, was just finishing off some ironing before settling down—inspired by the telephone disaster—to tackle a tottering pile of other unpaid bills. Ah, the lives of white-hot British stars and the women who love them.

"When someone says, 'Do you want to be in a new Star Wars movie?' it would take a bigger man than me to say no."

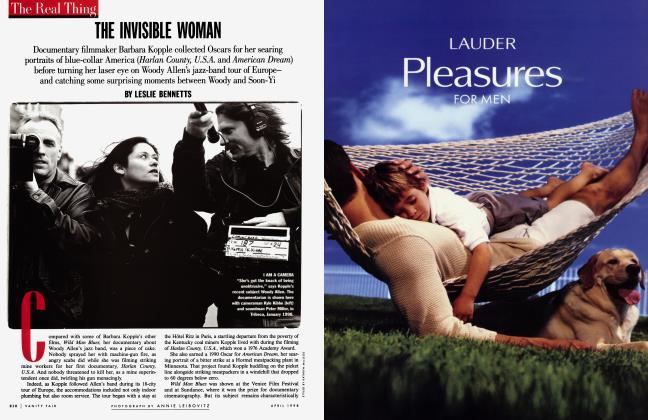

'You know how swimming naked is such a lovely feeling? Well, being naked on set is kind of a bit like that. It makes you feel powerful, I suppose." In a polite little restaurant in Primrose Hill, over a bottle of white wine and a plate of liver and mashed potatoes, McGregor is discussing Velvet Goldmine, a phantasmagoric eulogy to the glam-rock era in which he plays Curt Wild, a drug-blurred 70s rock singer, based to a large extent on the real-life icon Iggy Pop. McGregor manages, in the course of his performance, to share rather more of his physical self with the audience than is generally expected from legitimate actors. This is not a first. His propensity for appearing in uninhibited nude scenes—most notably in Peter Greenaway's The Pillow Book—has been the source of much amused chatter in Britain for a while now. (One magazine profile of the actor ran with the headline I DO HAVE A VERY LARGE PENIS.) "It does get written about a lot," McGregor says, sighing. "Let's try and do it in a new way. How about I show it to you right now? 'At this point, Ewan slopped his cock into the mashed potato.'" He laughs uproariously.

In preparation for his Velvet Goldmine role, McGregor spent a lot of time studying tapes of Iggy Pop, in order to capture something of the man's id-in-excelsis stage presence. Having seen the film twice, he feels pretty confident that he did a good job. "When I saw the movie at the Edinburgh International Film Festival ... I was truly shocked. I was like 'Look what I'm doing. Look what I'm doing.' I was truly exhilarated by watching myself. Does that sound arrogant? It's because I wasn't in control of myself when I was doing it."

In perhaps the most memorable scene of the movie, McGregor appears at an open-air concert before a large, disenchanted crowd and proceeds to stir them into a hostile fury with a decadent show that features stage-diving, spitting, large amounts of glitter and oil, and generous exposure of his genitalia. If this sounds rather revolting, it is—while also managing to be exciting, funny, and quite sexy. McGregor makes a frighteningly charismatic rock star.

"That was the heart of my performance," McGregor says fondly. "That's what that whole film will always be about for me.... The thing is, I enjoy extraordinary situations. . . I thrive on excess in lots of respects. When I was standing onstage at four in the morning in front of 400 extras—drunk, pulling my penis, bending over and showing them my arsehole—that was an extraordinary situation to find myself in. I got such a buzz out of it.... The first time I did a take, I turned around at the end and everyone—the crew, the extras—was literally speechless. It was a great moment. Nobody had anything to say."

In addition to making us familiar with all of McGregor's bit, Velvet Goldmine also gives us the actor in the throes of gay sex. Together with nudity, a permissive, polymorphous sort of libidinousness has been a regular characteristic of McGregor's film roles thus far. One of his interesting and peculiarly modem talents is his capacity for communicating a sexuality that is distinctively male yet devoid of machismo. "Ewan was very cool about the sex scenes," director Todd Haynes says. "I'm not sure an American actor of his age would have been so relaxed. Americans tend to get worried about portraying gay characters—how it will affect their careers. When they do sex scenes, they tend to leap up as soon as you say 'Cut' and start punching walls and joking around with the crew, to reassert their masculinity. Ewan wasn't like that at all.... When he was doing scenes with Christian [Bale], the two of them would stay in an embrace between takes, and continue to be tender to one another, shutting out the crew. I felt incredible admiration for how secure about their sexuality they were."

"It's actually much more exciting being in a sex scene with a man," McGregor says. "It's something outside of my normal experience. It's another example of an extreme situation—snogging a man."

McGregor, it may be ventured, is a surprising person to find defending George Lucas's Empire in a Star Wars movie. It is not just that he is waggling his willy and snogging men on a screen near you this winter. There is also the fact that, to date, his prodigious work record has been restricted largely to small, or teeny, independent, European productions. Nightwatch, a thriller in which he appeared earlier this year, with Nick Nolte and Patricia Arquette, is the one major exception, and the mere mention of that film prompts him to let out a low yowl of horror. McGregor chose to spend this year on the following projects:

Little Voice—a small British film directed by Mark Herman, based on the play The Rise and Fall of Little Voice. McGregor's part as a nerdy adolescent pigeon-fancier was minuscule, but he took it "because I'd never played anyone like that before."

Little Malcolm and His Struggle Against the Eunuchs—a fringe production of David Halliwell's 1960s play, directed by the actor Denis Lawson, McGregor's uncle.

The Eclair—a surrealist six-minute short, made by a friend of his, in two days, on a Scottish beach.

The director Danny Boyle, along with the writer John Hodge and the producer Andrew Macdonald, has made three films with McGregor thus far—Shallow Grave, Trainspotting, and A Life Less Ordinary. Boyle has spoken in the past of finding it "frustrating" to see McGregor spreading himself so thin, with so many small projects. But McGregor is dismissive. "I think maybe they were worried in case I was in anything crap, because they thought it would reflect badly on them."

"Ewan wants to grow as an actor," says Lindy King, who has presided over McGregor's unorthodox career choices. "Actors don't really do repertory theater anymore—so Ewan has been using the last couple of years as his own repertory experience on-screen."

Clearly, the role of Obi-Wan Kenobi constitutes something of an aberration on McGregor's resume, and he did, he says, have some hesitations about it. He is now committed to the next two films in the new Star Wars trilogy. "I thought about it for a long time," he says. "I knew it was going to be enormous when it came out, and I've never been in anything like that before. I wondered how it would juxtapose with the other work I was doing. Some of the actors in the original Star Wars didn't do anything else afterwards, and I wondered, Is that going to happen to me?"

One of the people he went to for advice was his uncle, who appeared as Wedge, the space-age pilot in the first trilogy. Lawson initially advised his nephew against taking the part, warning that he would find the shoot a tedious, technology-bound business. In the end, however, the Empire won out. "I mean," McGregor says, shrugging, "when someone wanders up and says, 'Do you want to be in a new Star Wars movie?' it would take a bigger man than me to say no."

His uncle was right, though. Acting is not the main event in a project like Star Wars. "This film was two years in pre-production," McGregor says. "We shot for three and a half months, and then it was 18 months in postproduction, so it shows you how important my part in the film was.... A lot of the time on the set, it's 'Oh, don't worry about that—we can do it later.'" For an actor eager to "grow," playing Obi-Wan—endlessly post-synching lines like "I think the hyperdrive generator is broken"—offers few opportunities for refining one's craft. Still, whatever longueurs McGregor suffered during the shoot were amply recompensed when George Lucas recently showed him some rough-cut excerpts of the film. McGregor was transfixed, he says, by the sight of himself wielding a light saber. "Oooh! I nearly shat myself! I just about died with excitement! I mean, no one gets to do that—but I did."

Despite the alienating effects of the technology, McGregor got on very well with his director, it seems. Once, Uncle Denis came to visit the set and remarked on the fact that Lucas was wearing the same shirt he had worn during the original Star Wars shoot. McGregor—who himself has been wearing the same, extremely worn, red suede biker jacket for as long as anyone can remember—seems to have been enchanted by this fact. "He's lovely," he says of Lucas. "He likes a good chat: he'll talk to you for hours about his world and what goes on in it. He's kind of like a king—not in the way he behaves, but just because he lives in his own world. His ranch—the Skywalker Ranch—is built in this big valley in Northern California, and he owns the valley. I imagine his house way up at the top and everybody else, all the producers and these thousands of people who work for him, living sort of below him—kind of like the old feudal system. He's in charge of so many different things—he's the boss—and he's fucking loaded. He's a billionaire, a multibillionaire." McGregor pauses. "Well, I don't know about multibillionaire, but he's got a lot of cash. A lot of lolly."

This sort of cheery naïvete frequently infects McGregor's conversation. It is part of what has made him beloved by his countrymen. McGregor, it is understood, is a bloke's bloke—someone who knows how to have a good laugh and enjoy a pint. "Ewan's got a rock-solid quality," says his old friend from drama school Jeremy Spriggs. "There's just this incredible integrity to him." As is regularly pointed out in Britain, McGregor cannot claim an authentic working-class background. He and his older brother (now a fighter pilot in the British air force) were raised in a solidly middle-class home in the small town of Crieff, near Edinburgh. Their parents, who are both retired, were schoolteachers, and while McGregor did leave school at 16, he did so only in order to attend a one-year drama course at the Perth Repertory Theatre, before going on to study acting at London's Guildhall School of Music & Drama. But in spite of these bourgeois credentials, McGregor has managed to establish himself as a sort of folk hero. He's the honest lad, still deeply attached to his Scottish roots, who returns frequently across the border to visit his parents. "When I first met him, on a set in Limerick," Haynes says, "his parents were visiting him and we all went to the pub and drank Guinness. There's obviously such love in that family. You could tell a lot about the stability he comes from—from watching them together. I mean, when they said good-bye, his dad kissed him on the lips."

Britain may not have the infrastructure or the will to provide its A-list with Hollywood-style pampering (forget home-visit aromatherapists or personal stylists—this is a country where getting a massage is still considered a rather ludicrous, namby-pamby pastime), but it doesn't like it when stars leave. McGregor, with his close family and his candid, studiously modest ways, holds out the promise of a homegrown star who won't let fame go to his head, or abandon his country. He's not the type to get taken in by celebrity hoopla ("Oh, it's out of control in Los Angeles, isn't it?" he says, shaking his head. "Stars are like royalty there, aren't they?"). What brief brushes he has had with the Los Angeles high life have left him, he claims, distinctly underwhelmed: "I stayed at the Mondrian once. God! All these snotty wee guys in suits came running out to the driveway and told my cab to move on. Then when they realized I was actually staying there, they're all 'Oh, sorry, sir, please let us help you ... ' They said to me, 'Well, obviously, you're familiar with the Skybar.' I said, 'No, never heard of it,' and they all started laughing: 'Oh! My Gad! Can you believe it, he's never heard of the Skybar!"'

"Everyone loves Ewan," says Olivia Stewart, a co-producer on two of his movies, Velvet Goldmine and Brassed Off. "He doesn't incite the usual British nastiness.... Ewan is so utterly unpretentious and unjaded, he doesn't get criticism."

If there is a danger, it is that McGregor can sometimes be heavy-handed with his vaunted integrity. In his role as plainspoken man of the people and scourge of pretension, he can often sound a little righteous. "I have a very high horse and I'll jump on it a lot," he acknowledges. "I know that about myself. I fire off on both barrels sometimes when maybe I should just fire off on one." Recently, he was quoted in the British newspapers lambasting British producers for the poor treatment they give their film crews. "If you're going to do interviews, then why not talk about something that matters?" McGregor says. "I was looking out for the crews of Britain—the people who put me on the screen. My dad rang me and said, 'Oh, Ewan, what have you done? You've said all these things ... ' I said, 'What's wrong with any of it? It's all important things to say. The reason that you're worried about it, Father, is people don't normally say it.'"

A week or so before I met McGregor, a reporter at the Deauville Film Festival had asked him whether he shared Sean Connery's views on Scottish nationalism, and McGregor had replied that he resented being told how to feel about Scotland—"especially by someone who hasn't lived there for 25 years." This pointed reference to Connery's exile in Marbella and the Bahamas had been picked up by the papers, and on the day I went to visit McGregor, the Scottish tabloid the Daily Record was running a front-page story about McGregor's comment, headlined EWAN FEUD WITH SEAN. (The paper had also set up a phone-in poll asking its readers, "Are you for Ewan or for Sean?") In response, the Scottish Nationalist Party called McGregor's parents requesting a meeting with their son to discuss his stance on Scottish nationalism. McGregor ended up having a conciliatory session with the S.N.P. leader, Alex Salmond, as well as an apologetic—and, one imagines, awkward—phone conversation with Connery.

A few months ago, he created another minor storm in Britain by publicly criticizing the actress Minnie Driver for allowing herself to be seduced by Tinseltown. "She's completely reinvented herself," he said. "She's gone mad, mad. She goes to the opening of an envelope, she wears those little dresses all the time.... Och, I am so disappointed in her.... Why has she bothered buying into all that rubbish?" While McGregor now regrets these remarks—"I feel terrible about that . . . If you see Minnie anywhere, will you tell her I'm sorry?"—he remains unrepentant about the anti-Hollywood sentiment. "They're all bastards ... the studio executives, the studio people, the people who live in L.A.," he says. "I can't remember the last time there was a really good studio picture."

McGregor briskly denies that this thoroughgoing contempt might jar with his role in the Star Wars trilogy. "A film like Independence Day, that's what I hate—those are the people who don't deserve to be making movies. Star Wars is a completely different ball game. Those movies stand on their own, they're unique. They're legends, they're kind of our modem fables—they were for me as a kid. They're not studio product, they're Lucas's pictures—he does them on his own and then sells them to Fox or whatever. They don't go through a committee of 18 screenwriters—he writes them. And they don't get screen-tested."

If anything, McGregor's contempt for West Coast glamour has been boosted recently by the news that his erstwhile collaborators Danny Boyle, John Hodge, and Andrew Macdonald have decided to cast Leonardo DiCaprio instead of him in their next movie, an adaptation of Alex Garland's novel, The Beach. McGregor, who until now has seemed to function as an in-house muse for the filmmaking trio, takes on a betrayed tone when speaking about this. "I was gutted. Fucking gutted_It's been kind of like a love affair between Danny and me—and now he's seeing someone else." Boyle says he has been talking to DiCaprio about working together since Trainspotting. "He liked the film a lot; he's actually a big fan of Ewan's"—but he admits that the decision not to use McGregor has been "difficult for all of us. . . It came down to money," he says.

"This is the most expensive film we've made, and we realized we had to find a way to include America in it more." McGregor, while insisting that he wants to work with Boyle again, is skeptical. "The way he explained it, it was purely financial—they would get more money from the studio if they had DiCaprio. But then, they're paying DiCaprio so much more money than I would be paid, it kind of defeats that argument.... Success in America seems to be their goal at the moment. It never was our goal before, so I don't understand why it's suddenly the mission. I didn't think that was the point."

Back at the Belsize Park apartment, McGregor is taking a bath with his daughter, Clara. Eve is making dinner and talking about Velvet Goldmine. "There he is, having a gay relationship with two different men—I didn't think I could ever relate to that. But actually I found it rather sexy." The only time she was unnerved by her husband's onscreen sexual adventures, she says, was during Trainspotting, when she was three months pregnant. "Ewan had a sex scene with the actress Kelly Macdonald. Poor Kelly—she's a lovely girl—but at that time I just had a full-blown jealousy thing. If I saw her, my heart started beating fast, I would get out of breath. I could hardly speak to her." She laughs. "It's very weird, but that's the only time."

McGregor emerges from the bathroom, Clara is put to bed, and we all settle down to watch The Eclair on video before dinner. In January, McGregor will be directing his own short film, one in a commissioned series entitled "Tube Tales." Early next year, McGregor will also star as James Joyce in Nora, the first feature film to be produced by Natural Nylon, a production company he has set up with fellow British actors Jude Law, Sean Pertwee, Jonny Lee Miller, and Sadie Frost. "If I was in L.A., being handled by CAA," he notes, "I wouldn't be allowed to do all this. You know, Leonardo DiCaprio has got to the stage where he's getting $21 million a picture. His agents want him to be the most expensive actor in Hollywood—they don't want to nurture him into being a brilliant actor, or make him happy with his work. They want to be able to say, 'He is now the most expensive actor in Hollywood'—until the next one comes along and they fucking chuck Leo and they get the new guy on."

While one doesn't doubt the sincerity of McGregor's commitment to his modest, worthy projects, one can't help noticing that the premiere of Star Wars is fast approaching—and with it the moment when McGregor, whether he likes it or not, will make an exponential leap from local hero to global celebrity. Even as we sit here, watching surrealist shorts, the mold for a billion little Ewan-like Obi-Wan toy figures is being cast. McGregor acknowledges that the inevitable dust storm of Star Wars publicity is a daunting prospect. "Whenever I do a press junket," he says, "I always get really depressed afterwards.... Frightened about what I've said. The idea of it—why is everybody so interested? Why am I the one? There are moments of real, sweaty terror in the middle of the night. Panicking. Panicking. Not being able to sleep because it's not natural to talk about yourself all day."

The popular expectation is very much that "our Ewan" won't be changed by success. Oh, perhaps the bohemian disarray of his living quarters will improve a little. Eventually, he may even splash out on a car. (At the moment, the McGregor family travels by motorbike and taxicab.) But McGregor will always be the simple, unaffected lad from Crieff. "He's a phenomenon now," says Jeremy Spriggs. "But I think he'll handle the fame. He has the control mechanisms—Eve, Clara, his mum and dad and brother. As long as they stay in place, I don't have any worries."

McGregor's wife, however, is slightly more circumspect about her husband's impending superstardom.

"Ewan is very close to his family. I am very close to my family. We have the same values. We're not really into things. But you know, it's quite pernicious, the way it hits you. The papers always say, 'Oh, Ewan, he's so nice, so grounded,' but I mean, Ewan is a nice guy, so even if he's not grounded, he's going to be nice.... It's more pernicious the way it comes in. It has other ways to touch people and to hurt them. I'm not sure of it yet." She smiles. "I'm still watching."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now