Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

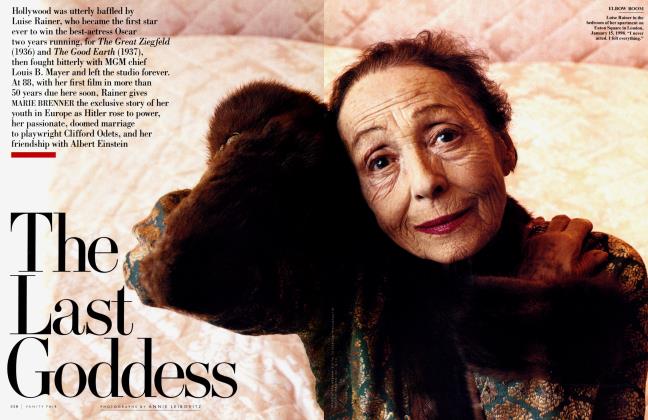

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE INVISIBLE WOMAN

The Real Thing

Documentary filmmaker Barbara Kopple collected Oscars for her searing portraits of blue-collar America (Harlan County, U.S.A. and American Dream) before turning her laser eye on Woody Allen’s jazz-band tour of Europe— and catching some surprising moments between Woody and Soon-Yi

LESLIE BENNETTS

Compared with some of Barbara Kopple’s other films, Wild Man Blues, her documentary about Woody Allen’s jazz band, was a piece of cake. Nobody sprayed her with machine-gun fire, as angry scabs did while she was filming striking mine workers for her first documentary, Harlan County, U.S.A. And nobody threatened to kill her, as a mine superintendent once did, twirling his gun menacingly.

Indeed, as Kopple followed Allen’s band during its 18-city tour of Europe, the accommodations included not only indoor plumbing but also room service. The tour began with a stay at the Hotel Ritz in Paris, a startling departure from the poverty of the Kentucky coal miners Kopple lived with during the filming of Harlan County, U.S.A., which won a 1976 Academy Award.

She also earned a 1990 Oscar for American Dream, her searing portrait of a bitter strike at a Hormel meatpacking plant in Minnesota. That project found Kopple huddling on the picket line alongside striking meatpackers in a windchill that dropped to 60 degrees below zero.

Wild Man Blues was shown at the Venice Film Festival and at Sundance, where it won the prize for documentary cinematography. But its subject remains characteristically gloomy about its commercial prospects. “I think no one will be interested in this film,” Woody Allen says. “People are not interested in documentaries, they are not overly interested in me and my films, and they’re not interested in New Orleans jazz, especially the way I play it.”

"When people tell me something can’t be done,” says Kopple, “I just listen and smile and think, Of course it can.”

But American audiences may well be fascinated by the intimate moments between Allen. and his then girlfriend, Soon-Yi Previn, whom he married in December. After the 1992 scandal surrounding their clandestine affair and Allen’s breakup with Previn’s adoptive mother, Mia Farrow—not to mention the child-sex-abuse allegations and the ensuing legal battles over Allen’s access to his and Farrow’s children—there is undeniable prurient interest in observing Allen and Previn eat breakfast a deux, take their morning showers, swim in the lap pool of their palatial Viennese hotel suite, and cope with Allen’s assorted anxieties, complaints, and demands.

Although Previn is only 27 and Allen is 62, she is so assertive that she seems domineering. In virtually every frame she is either criticizing or bullying him, to the point where the film’s title begins to seem unintentionally funny; it might more aptly have been called Mild Man Blues. In one scene, room service delivers an omelette which Previn claims is inedible; she snatches Allen’s breakfast and makes him eat hers, blithely ignoring his ineffectual protests.

At one point Allen makes an acid reference to her pre-adoption background—“this kid who was eating out of garbage pails in Korea,” as he puts it. But in general he plays Caspar Milquetoast to Previn’s dominatrix—a dynamic whose origins are suggested at the end of the film during Allen’s obligatory return visit to his parents in Brooklyn. Although Martin and Nettie Konigsberg are both in their 90s, they continue to carp and cavil, insisting that their famous son is no great shakes and that whatever he has achieved he is only what they made him. Woody may be famous, but his parents still think he should have become a pharmacist. Suddenly it doesn’t seem surprising that he has married a woman who claims never to have seen Annie Hall or Manhattan, and who says she has never read anything he’s written.

The box-office appeal of Allen en famille doesn’t concern Kopple; she doesn’t choose projects for their commercial potential. They have won acclaim nevertheless. She is the only female feature-documentary filmmaker ever to have earned two Academy Awards, and at 51 (her age varies depending on which day you ask) she is a generation younger than the other leading lights in her field. In a Richard Avedon photograph hanging at the entrance to her office, Kopple’s come-hither sultriness offers quite a contrast to D. A. Pennebaker’s Santa-like figure and the craggy faces of Frederick Wiseman and Alfred Maysles (with whom Kopple apprenticed).

All three men have had long careers. Pennebaker’s oeuvre ranges from Don’t Look Back, which followed Bob Dylan’s 1965 English tour, and 1969’s Monterey Pop, the first major rockconcert film, to a documentary about the 1992 presidential campaign, The War Room. With Pennebaker and others, Maysles co-directed the landmark 1960 political documentary Primary. His more recent films include 1996’s Letting Go: A Hospice Journey, and Abortion: Desperate Choices, which won a 1995 Peabody Award. Frederick Wiseman has specialized in American institutional life, from his first documentary, Titicut Follies, about life in a prison for the criminally insane, to High School, Law and Order, Hospital, Juvenile Court, and Welfare.

But among younger filmmakers, Kopple is renowned. John Scher, president and C.E.O. of the Metropolitan Entertainment Group, says, “Barbara Kopple is the premier American documentarian right now.”

In the light-filled SoHo loft that serves as headquarters for her company, Kopple alternates between squirming like a coquettish little girl and flinging around her long jet-black mane. She is wearing her usual uniform: black tights, little black boots, and a black top (which, on my various visits, consisted of sensuous velvet shirts and, on one occasion, a formfitting lace number). The all-black attire suggests a sort of camouflage—understandable enough in a filmmaker whose job is to remain in the shadows while letting life unfold in front of her. But on some level, it is apparent that Barbara Kopple wants very much to be noticed.

In the early years of her career, when she was young, unknown, inexperienced, underfinanced, and sometimes in terrible danger, her looks—and how she used them—surely contributed to her success. “She was absolutely drop-dead beautiful,” says Tom Hurwitz, the director of photography for Wild Man Blues. “Not only was she stunning, she was small, and men couldn’t really believe that somebody that cute can be so intelligent.”

Kopple also tends to utilize an itsy-bitsy baby-doll voice that provides a useful distraction from her laserlike focus. Her gaze is penetrating, but her normal manner is coy rather than forthright, even with women. “Think of yourself as a Kentucky sheriff, being presented with that voice,” explains Hurwitz. “It’s completely disarming; you think, Oh—I’m dealing with a little girl! And us big men have a way of reacting to a little girl: we feel protective, and all the juices start running.” Affecting a lascivious tone, he drawls, Hiiii', little lady!’” He laughs. “She can wheedle, she can cry, she can bully—Barbara uses every tool at her command to get her stuff done.”

While she’s filming, Kopple has to make her subjects forget she is there. “She’s got the knack of being unobtrusive,” says Woody Allen. “Once you get used to it, the camera doesn’t alter your behavior at all.”

Acually, Kopple’s subjects often realize with chagrin just how completely they have let their guard down. John Scher was president of PolyGram Diversified Entertainment when Kopple was hired to make Woodstock II, a documentary about the 1994 Woodstock festival. He recalls one executive meeting in which the discussion revolved around how many prophylactics to buy for the concessions. “I clearly forgot she was there,” Scher says sheepishly. “You hear me saying, ‘Hundreds of thousands of kids are coming, we’re telling them they can’t bring booze, can’t bring drugs—what do you think they’re going to do? They’re going to fuck/’” He sighs. “I’m not sure how I’m going to explain that to my 12-year-old daughter, but it’s the best example I can give you of what an effective documentarian Barbara is.”

Her drive to succeed is overwhelming. “That’s what distinguishes her from all the other talents out there,” says Hurwitz. “She is relentless.”

“When people tell me something can’t be done, I just listen and smile and think, Of course it can be done,” Kopple says. “I guess I like the chase. I like being able to do things people say you can’t do; it excites me. It generates great energy.”

Both of her Oscar-winning films took years to complete, and she is currently in the throes of another tortuous saga. Kopple began filming the Woodstock documentary in early 1994, but after several months PolyGram changed its mind and terminated the project. Kopple went right ahead with it. Four years later she is still struggling to find the money to complete the film, which is now called Generations.

Her perseverance is in stark contrast to many contemporaries who have been defeated by ever increasing odds. “Back in the 1960s, documentaries were very hot, and there was a big crowd of people making them,” says Peter Biskind, author of Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock-and-Roll Generation Saved Hollywood. “As the political climate changed and the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities stopped giving money, people dropped by the wayside,” Biskind explains. “Being a documentary filmmaker is really hard; it’s analogous to pushing a boulder up a hill. Barbara is one of the few who started in the 60s who continued.

I think people who have hung in there are really heroic.”

The source of Kopple’s determination remains mysterious; her early years give no hint of what was to follow. She was raised in privileged Scarsdale as the daughter of a New York textile executive and his homemaker wife, both of whom, she says, adored her. “I was made to feel there was nothing I couldn’t do in my life,” Kopple says. But from the time she left home her life took a very different trajectory from the comfortable affluence of her youth. First she headed for college in West Virginia, an odd choice for a Scarsdale girl. “When you’re that age, you want to explore,” she says. “I go on journeys. I go places people maybe haven’t been.”

She spent most of her time hanging out in a “holler” called Cabin Creek, the name she later chose for her film company. “It was the poorest of the poor, a place where young girls are prostitutes at 12 and 13 years old, where they have no indoor plumbing, where everyone’s struggling to survive—a place that depicts a lot of hopelessness,” says Kopple, who later attended Northeastern University but eventually dropped out of college. “I had never seen anything like this. It was a place that had such an impact on me that I wanted to make films about people you wouldn’t ordinarily hear about. I chose the name for my company as a reminder.”

Although it has been more than two decades since then, Kopple still hasn’t forgotten. Even when she is telling the story of someone rich and famous, there tends to be a poignant subtext, as in the powerful portrait of Mike Tyson in her 1993 documentary, Fallen Champ, which evokes the harshness and emotional deprivation of his upbringing.

In recent months, Kopple has been shooting in Sarajevo, Cambodia, and South Africa. Her current projects include a Lifetime Television documentary called Defending Our Daughters: The Rights of Women in the World, which provides a harrowing look at the mistreatment of women in other countries, from the use of rape as a weapon of war in Bosnia to the genital mutilation inflicted on 130 million living African and Egyptian women. When I ask Rosemary Sykes, the director of programming at Lifetime, why Kopple was chosen for the project, Sykes replies, “She has a unique ability to find the small, personal stories that really explain the big story.”

Kopple’s personal life is actually quite bourgeois; she lives in SoHo with her second husband, a former union organizer, and her 16-year-old son, a Dalton student whose father is Kopple’s first husband (and former cinematographer), Hart Perry.

But Kopple hasn’t lost her taste for the exotic. “I love going on adventures and doing things I’ve never done before,” she says. “I come alive when I’m working.” She is hoping that this year she will finally complete the Woodstock film. “Doing the project is worth everything to me,” she says. “It’s not in my nature to get discouraged.”

Those who know her have no doubt about what lies ahead. “When she goes up and accepts her third Oscar for this film, she’ll never even say, ‘You bastards!”’ John Scher predicts. “She’ll probably go and thank them.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now